Gad (deity)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

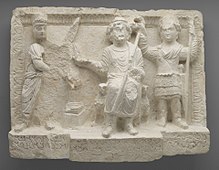

Gad was the name of the pan-Semitic god of fortune, usually depicted as a male but sometimes as a female,[2] and is attested in ancient records of Aram and Arabia. Gad is also mentioned in the bible as a deity in the Book of Isaiah (Isaiah 65:11 – some translations simply call him (the god of) Fortune), as having been worshipped by a number of Hebrews during the Babylonian captivity.[3] Gad apparently differed from the god of destiny, who was known as Meni. The root verb in Gad means cut or divide, and from this comes the idea of fate being meted out.[4]

Israelite connection

It is possible that the son of Jacob named Gad is named after Gad, or that Gad is a theophoric name, or a descriptive.[5] Although the text presents a different reason, the (ketub) quotation of Zilpa (Gad's mother) giving the reason of Gad's name could be understood that way.

How widespread the cult of Gad, the deity, was in Canaanite times may be inferred from the names Baalgad, a city at the foot of Mount Hermon, and Migdal-gad, in the territory of Judah. Compare also the proper names Gaddi and Gaddiel in the tribes of Manasseh and Zebulun (Numbers 13:10, 11). At the same time it must not be supposed that Gad was always regarded as an independent deity. The name was doubtless originally an appellative, meaning the power that allots. Hence any of the greater gods supposed to favour men might be thought of as the giver of good fortune and be worshiped under that title. It is possible that Jupiter, the planet, may have been the Gad thus honoured; among the Arabs, the planet Jupiter was called the greater Fortune (Venus was styled the lesser Fortune).

Gad is the patron of a locality, a mountain (Kodashim, tractate Hullin 40a), of an idol (Genesis Rabbah, lxiv), a house, or the world (Genesis Rabbah, lxxi.). Hence "luck" may also be bad (Ecclesiastes Rabbah, vii. 26). A couch or bed for this god of fortune is referred to in the Mishnaic tractate Nedarim 56a).

Citations

- ^ Kropp 2013, p. 225.

- ^ Niels Gutschow; Katharina Weiler (26 November 2014). Spirits in Transcultural Skies: Auspicious and Protective Spirits in Artefacts and Architecture Between East and West. Springer. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-3-319-11632-7.

- ^ Karel van der Toorn; Bob Becking; Pieter Willem van der Horst (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2.

- ^ van der Toorn, Becking & Willem van der Horst 1999, p. 339.

- ^ Karel van der Toorn; Bob Becking; Pieter Willem van der Horst (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 340–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2.

Sources

- Kropp, A.J.M. (2013). Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC - AD 100. Oxford Studies in Ancient Cult. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-967072-7.

- van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Willem van der Horst, Pieter (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802824912.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Gad". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Gad". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Further reading

- Thomas, Ryan (2021). "The God Gad". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 139 (2): 307–316. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.139.2.0307..