Emma Smith

| Emma Hale Smith Bidamon | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo | |

| March 17, 1842 – 1844 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| Successor | Eliza R. Snow |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Emma Hale July 10, 1804 Harmony Township, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 30, 1879 (aged 74) Nauvoo House, Nauvoo, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Smith Family Cemetery, Nauvoo 40°32′26″N 91°23′31″W / 40.5406°N 91.3920°W |

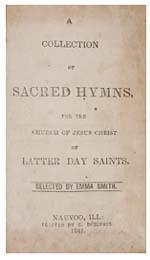

| Notable works | A Collection of Sacred Hymns Latter Day Saints' Selection of Hymns |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 11 (see Children of Joseph Smith) |

| Signature | |

Emma Hale Smith Bidamon (July 10, 1804 – April 30, 1879) was a leader in the early Latter Day Saint movement and a prominent member of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church) as well as the first wife of Joseph Smith, the movement's founder.[1] In 1842, when the Ladies' Relief Society of Nauvoo was formed as a women's service organization, she was elected by its members as the organization's first president.

After the killing of Joseph Smith, Emma remained in Nauvoo rather than following Brigham Young and the Mormon pioneers to the Utah Territory. Emma was supportive of Smith's teachings throughout her life with the exception of plural marriage and remained loyal to her son, Joseph Smith III, in his leadership of the RLDS Church.[2]

Early life and first marriage, 1804–1829

Early life

Emma Hale was born on July 10, 1804, in Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, in her family's log cabin.[3][4] She was the seventh child and third daughter of Isaac Hale and Elizabeth Lewis Hale.[5] She was descended of primarily English ancestors,[6] including seven passengers on the Mayflower.[7] [8] Isaac and Elizabeth arrived in Susquehanna County in 1791 where they bought land and became the first permanent settlers.[9]

Isaac and Elizabeth were members of the first Methodist Episcopal congregation in Harmony, where Emma's uncle preached.[10] Beginning at age seven or eight, Emma was involved in the church, reading the Bible and singing hymns.[11][12] Emma's father stepped away from the church for a time and became a deist, but later returned to the church after Emma's requests.[5][12]

The Hale family was relatively wealthy.[5] Isaac hunted and Elizabeth hosted lodgers and boarders in their home.[10][12][13]: 53 The Hale family was known for being honest, hard-working, and generous to their neighbors.[12][5]

Throughout her childhood, Emma was interested in religion, canoeing, and riding horses.[5] Emma learned how to read and write and was considered to be intelligent.[12][14] She attended a girls school for a year [14] and taught school in Harmony when she returned.[15][12]

Courtship and marriage to Joseph

| Part of a series on the |

| Book of Mormon |

|---|

|

Emma first met her future husband, Joseph Smith Jr., in 1825. Joseph lived near Palmyra, New York, but boarded with the Hales in Harmony while he was employed in a company of men hired by Josiah Stowell and one of Emma's relatives to dig for money on the Hale family property.[16] Rumors about Joseph having a unique ability to find hidden treasure caused Stowell to offer him a high wage.[17] Although the company was unsuccessful in finding the suspected mine and Emma's father eventually turned against the project,[13]: 53 Joseph and Emma secretly met without her family's approval several times at a friend's house during the dig and after while Joseph was working as farmhand nearby.[18] When Emma and Joseph spoke to the Hales to receive a blessing on their marriage, Isaac and Elizabeth Hale refused; possibly because Isaac wanted Emma to marry a neighbor and he considered Joseph to be a "stranger" and possibly because of Joseph's failed money-digging operation on the Hale's land.[19][17] On January 17, 1827, Joseph and Emma left the Stowell house and traveled to the house of Zachariah Tarbill[20] in South Bainbridge, New York, where they were married the following day.[21][a]

On September 22, 1827, Joseph and Emma took a horse and carriage belonging to Joseph Knight, Sr., and went to a hill, now known as Hill Cumorah, where Joseph said he received a set of golden plates.[14][1]: 20–21 The announcement of Joseph having the plates created a great deal of excitement in the area. In December 1827, with financial support from Martin Harris,[1]: 8 the couple accepted and invitation from Emma's parents to move to Harmony. [22]

The Hales helped Emma and Joseph obtain a house and a small farm.[23] Once they settled in, Joseph began work on the Book of Mormon, with Emma acting as a scribe.[24] She became a physical witness of the plates, reporting that she felt them through a cloth, traced the pages through the cloth with her fingers, heard the metallic sound they made as she moved them, and felt their weight. She later wrote in an interview with her son, Joseph Smith III: "In writing for your father I frequently wrote day after day, often sitting at the table close by him, he sitting with his face buried in his hat, with the stone in it, and dictating hour after hour with nothing between us."[25][26] In Harmony on June 15, 1828, Emma gave birth to her first child – a son named Alvin – who lived only a few hours. He was buried east of their house. For the next two weeks, Emma remained gravely ill.[27]

Due to increased hostility towards Joseph as he worked on the Book of Mormon, Emma and Joseph went to live with David Whitmer in Fayette, New York, to finish the Book of Mormon. While there, both Emma and a schoolteacher named Oliver Cowdery worked as Joseph's scribes.[28] Joseph received a copyright for the Book of Mormon in June 1829 and the book was published in March 1830.[29]

"Elect lady" and the early church, 1830–1839

On April 6, 1830, Joseph and five other men established the Church of Christ.[30] Emma was baptized by Oliver Cowdery on June 28, 1830, in Colesville, New York,[21] surrounded by a group of mocking people.[31] Later that evening before the confirmation service, Joseph was arrested for being a disorderly person and causing an uproar by preaching the Book of Mormon. A few days later, Joseph was acquitted of all charges.[32] Emma was confirmed later by Joseph and Newl Knight.[33]

In July 1830, Joseph received a revelation, now known as Doctrine and Covenants Section 25, that highlighted Emma Smith as "an elect lady".[34][35] The revelation says that Emma would "be ordained under [Joseph's] hand to expound scriptures, and to exhort the church."[36] The revelation instructed Emma to "murmur not" and described Emma's duties to Joseph. Emma was also directed to be Joseph's scribe and to create a hymnbook for the new church.[35]

Joseph and Emma returned to Harmony for a time, but relations with Emma's parents remained strained.[23] Emma's father was displeased that Joseph and Emma were living off charity and Joseph was late to return money he borrowed to purchase a farm.[31] Many people in Harmony also openly opposed Joseph.[37] Emma and Joseph returned to live at David Whitmer's farm in August 1830.[37] This marked the last time that Emma saw her parents.[37] Despite the rift that her marriage to Joseph created in the family, Emma did reunite with her family. She communicated with her mother through letters. Some members of her family moved to Nauvoo although they did not accept Emma's invitation to join Mormonism.[38]

Emma and Joseph went back to staying in the homes of members of the growing church.[1]: 12 The couple lived first with the Whitmers in Fayette, then with Newel K. Whitney and his family in Kirtland, Ohio, and then in a cabin on a farm owned by Isaac Morley. It was here on April 30, 1831, that Emma gave birth to premature twins, Thaddeus and Louisa; both babies died hours later. That same day, Julia Clapp Murdock died giving birth to twins, Joseph and Julia. When the twins were nine days old, their father, John, gave the infants to the Smiths to raise as their own. On September 2, 1831, the Smiths moved into John Johnson's home in Hiram, Ohio. The infant Joseph died of exposure or pneumonia in late March 1832, after a door was left open during a mob attack on Smith.[39]

On November 6, 1832, Emma gave birth to Joseph Smith III in the upper room of Whitney's store in Kirtland. Young Joseph (as he became known) was the first of her natural children to live to adulthood. A second son, Frederick Granger Williams Smith (named after Frederick G. Williams, a counselor in the church's First Presidency), followed on June 29, 1836.[citation needed] As the Kirtland Temple was being constructed, Emma spearheaded an effort to house and clothe the construction workers.[41]

While in Kirtland, Emma's feelings about temperance and the use of tobacco[11] reportedly influenced her husband's decision to pray about dietary questions. These prayers resulted in the "Word of Wisdom". Also in Kirtland, Emma's first selection of hymns was published as a hymnal for the church's use. During the Panic of 1837, the Kirtland Safety Society, the banking venture that Joseph and other church leaders had set up to provide financing for the growing membership, collapsed, as did many financial institutions in the United States at that time.[citation needed] Emma herself held stock in the Society.[21] The bank's demise led to serious problems for the church and the Smith family. Joseph received revelation from God to leave Kirtland for the safety of his family, and on January 12, 1838, Joseph left for Missouri. Many faithful saints soon followed.

Emma and her family followed and made a new home on the frontier in the Latter Day Saint settlement of Far West, Missouri, where Emma gave birth on June 2, 1838, to Alexander Hale Smith. Events of the 1838 Mormon War soon escalated, resulting in Joseph's surrender and imprisonment by Missouri officials. Emma and her family were forced to leave the state, along with most other church members. She crossed the Mississippi River, which had frozen over in February 1839. Of these times, she later wrote:

No one but God knows the reflections of my mind and the feelings of my heart when I left our house and home, and almost all of everything that we possessed excepting our little children, and took my journey out of the State of Missouri, leaving [Joseph] shut up in that lonesome prison. But the reflection is more than human nature ought to bear, and if God does not record our sufferings and avenge our wrongs on them that are guilty, I shall be sadly mistaken.[42]

Early years in Nauvoo, 1839–1844

Emma and her family lived with friendly non-Mormons John and Sarah Cleveland in Quincy, Illinois, until Joseph escaped custody in Missouri. The family moved to a new Latter Day Saint settlement in Illinois which Joseph named "Nauvoo".[citation needed] On May 10, 1839,[21] they moved into a two-story log house in Nauvoo that they called the "Homestead". On June 13, 1840, Emma gave birth to a son, Don Carlos, named after his uncle Don Carlos Smith, Joseph's brother. Both Don Carlos Smiths would die the next year. The Smiths lived in the homestead until 1843, when a much larger house, known as the "Mansion House" was built across the street. A wing (no longer extant) was added to this house, which Emma operated as a hotel.[citation needed] She often took in young girls in need of work, giving them jobs as maids.[11]

On March 17, 1842, the Ladies' Relief Society of Nauvoo was formally organized as the women's auxiliary to the church. Emma became its founding president,[3] with Sarah M. Cleveland and Elizabeth Ann Whitney as her counselors.[citation needed] She had persuaded John Taylor and Joseph Smith to call the organization the "Relief Society" instead of the "Benevolent Society".[11] The Latter-Day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia records that Emma Smith "filled [the position] with marked distinction as long as the society continued to hold meetings in that city [Nauvoo]".[34] She saw upholding morality as the primary purpose of the Relief Society. As "protecting the morals of the community" became her mission, Smith supported the public confession of sins; on this subject, Smith called the women of Nauvoo to repentance with "all the frankness of a Methodist exhorter."[11] She served as president of the Relief Society until 1844.[41] According to the minutes of the founding meeting, the organization was formed to "provoke the brethren to good works in looking to the wants of the poor, [search] after objects of charity [and] to assist by correcting the virtues of the female community". Shortly before this, Joseph had initiated the Anointed Quorum – a prayer circle of important church members that included Emma.[citation needed] As she had in Kirtland, Emma Smith led "the work of boarding and clothing the men engaged in building [the Nauvoo temple]".[41] She also traveled with a committee to Quincy, Illinois, to present Illinois governor Thomas Carlin "a memorial ... in behalf of her people" after the Latter Day Saints had experienced persecution in the state.[41]

Rumors concerning polygamy and other practices surfaced by 1842. Emma publicly condemned polygamy and denied any involvement by her husband. Emma authorized and was the main signatory of a petition in summer 1842 with a thousand female signatures, denying Joseph Smith was connected with polygamy.[43] As president of the Ladies' Relief Society, she authorized the publishing of a certificate in October 1842 denouncing polygamy and denying her husband as its creator or participant.[44]

In June 1844, the press of the Nauvoo Expositor, a newspaper published by disaffected former church members, was destroyed by the town marshal on orders from the town council (of which Joseph was a member). This set into motion the events that ultimately led to Joseph's arrest and incarceration in the jail in Carthage, Illinois. A mob of about 200 armed men stormed the jail in the late afternoon of June 27, 1844, and both Joseph and his brother Hyrum were killed.

Later years in Nauvoo, 1844–1879

Upon Joseph's death, Emma was left a pregnant widow. On November 17, 1844, she gave birth to David Hyrum Smith, the last child that she and Joseph had together. In addition to being church president, Joseph had been trustee-in-trust for the church. As a result, his estate was entirely wrapped up with the finances of the church.[citation needed] Joseph had also been in debt when he died, leaving the responsibility to pay it on Emma Smith's shoulders.[11] Untangling the church's debts and property from Emma's personal debts and property proved to be a long and complicated process for Emma and her family.

Debates about who should be Joseph's successor as the leader of the church also involved Emma. Emma wanted William Marks, president of the church's central stake, to assume the church presidency, but Marks favored Sidney Rigdon for the role. After a meeting on August 8, a congregation of the church voted that the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles should lead the church. Brigham Young, president of the quorum, then became the de facto president of the church in Nauvoo.

Relations between Young and Emma steadily deteriorated. Some of Emma's friends, as well as many members of the Smith family, alienated themselves from Young's followers. Conflicts between church members and neighbors also continued to escalate, and eventually Young made the decision to relocate the church to the Salt Lake Valley.[citation needed] When he and the majority of the Latter Day Saints of Nauvoo abandoned the city in early 1846, Emma and her children remained behind in the emptied town.[41]

Nearly two years later, a close friend and non-Mormon,[citation needed] Major Lewis C. Bidamon, proposed marriage and became Emma's second husband on December 23, 1847.[21] A Methodist minister performed the ceremony. Bidamon moved into the Mansion House[34] and became stepfather to Emma's children.[citation needed] She and Bidamon had no children of their own.[3] Emma and Bidamon attempted to operate a store and to continue using their large house as a hotel, but Nauvoo had too few residents and visitors to make either venture very profitable. Emma and her family remained rich in real estate but poor in capital.

Unlike other members of the Smith family who had at times favored the claims of James J. Strang or William Smith, Emma and her children continued to live in Nauvoo as unaffiliated Latter Day Saints. Many Latter Day Saints believed that her eldest son, Joseph Smith III, would one day be called to hold the same position that his father had held. When he reported receiving a calling from God to take his father's place as head of a "New Organization" of the Latter Day Saint church, she supported his decision. Both she and Joseph III traveled to a conference at Amboy, Illinois. On April 6, 1860, Joseph was sustained as president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, which prefaced "Reorganized" to its name in 1872 and in 2001 became known as the Community of Christ. Emma became a member of the RLDS Church without rebaptism, as her original 1830 baptism was still considered valid.

Emma and Joseph III returned to Nauvoo after the conference and he led the church from there until moving to Plano, Illinois, in 1866. Joseph III called upon his mother to help prepare a hymnal for the reorganization, just as she had for the early church.

Smith and Bidamon bought and renovated a portion of the unfinished Nauvoo House in 1869. A few visitors from Brigham Young's faction of the Latter-day Saints came from Utah Territory to visit Smith at this house.[34] Emma died peacefully in the Nauvoo House[citation needed] on April 30, 1879, at the age of 74.[3] Her funeral was held May 2, 1879, in Nauvoo with RLDS Church minister Mark Hill Forscutt preaching the sermon.

Hymns and hymnals

Alongside W. W. Phelps, Emma Smith compiled a Latter Day Saint hymnal, published in 1835.[11] It was titled A Collection of Sacred Hymns, for the Church of the Latter Day Saints[21] and contained 90 hymn texts but no music.[citation needed] Forty-eight were written by Latter Day Saints, and the remaining forty-two were not.[11] The texts borrowed from Protestant groups were often changed slightly to reinforce the theology of the early church. For example, Hymn 15 changed Isaac Watts's Joy to the World from a song about Christmas to a song about the return of Christ (see Joy to the World (Phelps)). Many of these changes and a large number of the original songs included in the hymnal are attributed to W. W. Phelps.

Emma also compiled a second hymnal by the same title, which was published in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1841. This contained 304 hymn texts.

When her son Joseph III became president of the RLDS Church, she was again asked to compile a hymnal. Latter Day Saints' Selection of Hymns was published in 1861.

Polygamy

Polygamy caused a breach between Joseph and Emma.[45] Historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich argues that "Emma vacillated in her support for plural marriage, sometimes acquiescing to Joseph's sealings, sometimes resisting."[46] Although she knew of some of her husband's marriages, she almost certainly did not know the full extent of his polygamous activities.[47] In 1843, Emma temporarily accepted Smith's marriage to four women of her choosing who boarded in the Smith household, but later regretted her decision and demanded the other wives leave.[b] That July, at his brother Hyrum's encouragement, Joseph dictated a revelation directing Emma to accept plural marriage. Hyrum delivered the message to Emma, but she furiously rejected it.[48][c] Joseph and Emma were not reconciled over the matter until September 1843, after Emma began participating in temple ceremonies,[49] and after Joseph made other concessions to her.[d] The next year, in March 1844, Emma publicly denounced polygamy as evil and destructive; and though she did not directly disclose Smith's secret practice of plural marriage, she insisted that people should heed only what he taught publicly – implicitly challenging his private promulgation of polygamy.[50]

Despite her knowledge of polygamy, Emma publicly denied that her husband had ever taken additional wives.[51] While Smith was still alive, Emma spoke against polygamy,[52] and she (along with multiple other signatories directly involved in polygamy) signed an 1842 petition denying that Smith or his church endorsed the practice.[53] After his death, she continued to deny his polygamy. When Joseph III and Alexander specifically asked about polygamy in an interview with their mother, she stated, "No such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately, before my husband's death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of ... He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have".[54][e]

Many of the Latter Day Saints who joined the RLDS Church in the midwestern United States had broken with Brigham Young and/or James Strang because of opposition to polygamy. Emma's continuing public denial of the practice seemed to lend strength to their cause, and opposition to polygamy became a tenet of the RLDS Church. Over the years, many RLDS Church historians have continued to state that the practice had originated with Brigham Young.[55]

Children

Emma had eleven children with Joseph, five of whom lived into adulthood.

- Alvin Smith (born and died on June 15, 1828, in Harmony, Pennsylvania)[13]: 66–67 [56]

- Thaddeus and Louisa Smith (twins, born and died on April 30, 1831, in Kirtland, Ohio)

- Joseph and Julia Murdock Smith (adopted twins, Joseph died at eleven months old)

- Joseph Smith III (November 6, 1832 –December 10, 1914)

- Frederick Granger Williams Smith (June 20, 1836 – April 1862)

- Alexander Hale Smith (June 2, 1838 – 1909)

- Don Carlos Smith (June 13, 1840 – August 15, 1841)

- Unnamed son (stillborn, February 6, 1842, in Nauvoo, Illinois)

- David Hyrum Smith (November 1844 –August 1904)[56]

Notes

- ^ The marriage site is now the Afton Fairgrounds, located on New York State Route 41 on the east side of the Susquehanna River; and a New York State Historical Marker commemorates the location.

- ^ Park (2020, p. 152) summarizes, "Emma's support proved tenuous". The four women were Emily Partridge, Eliza Partridge, Sarah Lawrence, and Maria Lawrence; Emma Smith was not aware that Joseph Smith had already previously courted and married the Partridges, and they did not disclose this to Emma. See Davenport (2022, p. 138); Bushman (2005, p. 494); Remini (2002, pp. 152–53); and Brodie (1971, p. 339).

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints later canonized the text as D&C 132, in 1876; see Bringhurst, Newell G. "Section 132 of the LDS Doctrine and Covenants: Its Complex Contents and Controversial Legacy". Persistence of Polygamy. p. 60, in Bringhurst & Foster (2010, pp. 59–86)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Smith allowed Emma to destroy a copy of the revelation (though he had already had copies made), signed property over to Emma to give her and their children more independent financial security, and promised to not marry any additional women for the rest of the season. See Park (2020, p. 154): "after Joseph had copies made – she was allowed to express her frustration by destroying the document", and "Emma did not back down at all until Joseph promised not to take any more plural wives that fall. With one exception, he remained true to his word"; Davenport (2022, p. 144): "in November he [Smith] took his last plural wife – but he hardly relinquished 'all.' He even told William Clayton that 'he should not relinquish anything.' "

- ^ Historians have proposed several possible motivations for Emma Smith's continued denials of Joseph's polygamy. Brodie (1971, p. 399) speculates that the denial was a form of revenge and animosity against his plural wives; Van Wagoner (1992, pp. 113–114) posits that the subject of polygamy "evoked painful memories for Emma" and she "refused to give tongue to memory simply because she could not face the shadows of the past"; Newell & Avery (1994, p. 292) note that Emma received covenants associated with the temple and celestial marriage which involved strict promises to maintain secrecy; they argue Emma may have extended that secrecy to plural marriage itself which she never directly repudiated. Newell and Avery also aver that "when Emma decided not to tell her children about plural marriage, it was an attempt to remove problems from their lives."; Quinn (1994, p. 237) points out that Emma "opposed polygamy during most of the time her husband practiced it" and proposes that she did not teach her children about plural marriage because she "regarded it as the cause of his death"; Park (2020, p. 277) states that "denial" about polygamy was Emma's "method for dealing with" the experience "[a]fter years of anguish".

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Youngreen, Buddy (1982). Reflections of Emma: Joseph Smith's Wife. Grandin Book.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984.

- ^ a b c d McCune, George M. (1991). Personalities in the Doctrine and Covenants and Joseph Smith – History. Salt Lake City, Utah: Hawkes Publishing. pp. 108–109. ISBN 9780890365182.

- ^ Reeder 2021, pp. xiii, 8.

- ^ a b c d e Newell & Avery 1984, p. 3.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, pp. 4, 8.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (18 December 2020). "Joseph and Emma Share a Common Heritage". Joseph Smith Jr and Emma Hale Smith Historical Society. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

These Mayflower passengers are: John Tilley, Joan Hurst Tilley, Elizabeth Tilley, John Howland, Edward Fuller, Mrs. John Fuller, Samuel Fuller.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 4.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 2.

- ^ a b Newell & Avery 1984, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Compier, Don H. (1986). "The Faith of Emma Smith". The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal. 6: 64–72. JSTOR 43200764 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e f Reeder 2021, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Bushman, Richard L. (2007). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-7753-3.

- ^ a b c Newell & Avery 1984, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 6.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 17.

- ^ a b Reeder 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, pp. 1, 17.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 18.

- ^ Susan Evans McCloud (1 February 2016). "The Courtship and Marriage of Emma Hale and Joseph Smith". Retrieved 11 July 2021 – via Deseret News.

- ^ a b c d e f "Emma Hale Smith – Biography". The Joseph Smith Papers. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 20.

- ^ a b Newell & Avery 1984, p. 24.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 25.

- ^ "Last Testimony of Sister Emma" in History of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, 8 vols. Independence, Missouri: Herald House, 1951, 3:356.

- ^ "Last Testimony of Sister Emma". The Saints' Herald. 26 (19): 289–290. 1 October 1879. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 27.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 30.

- ^ In 1838, the name was changed to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints: Manuscript History of the Church, LDS Church Archives, book A-1, p. 37; reproduced in Dean C. Jessee (comp.) (1989). The Papers of Joseph Smith: Autobiographical and Historical Writings (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book) 1: 302–303.

- ^ a b Newell & Avery 1984, p. 32.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Newell & Avery 1984, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Jensen, Andrew (1941). Latter-Day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News. pp. 692–693.

- ^ a b Newell & Avery 1984, p. 33.

- ^ "Emma's 1835 Hymnal". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Newell & Avery 1984, p. 35.

- ^ Reeder 2021, pp. 11–12.

- ^ "Julia Murdock Smith Dixon Middleton Family album and history".

- ^ Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women's Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870. First Edition. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. page 165

- ^ a b c d e Jensen, Andrew (1941). Latter-Day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News. pp. 196–197.

- ^ Carol Cornwall Madsen. "The Letters of Joseph and Emma Smith". Retrieved 11 July 2021 – via The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

- ^ Times and Seasons 3 [August 1, 1842]: 869.

- ^ Times and Seasons 3 [October 1, 1842]: 940.

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 494–495)

- ^ Ulrich (2017, p. 89); see Park (2020, pp. 193–194) for a concurring assessment.

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 439)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 340–341); Hill (1989, p. 119); Bushman (2005, pp. 495–496); Ulrich (2017, pp. 92–93); Park (2020, pp. 152–154)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 494–497); Quinn (1994, p. 638)

- ^ Park (2020, pp. 195–196)

- ^ Van Wagoner (1992, pp. 113–114); Quinn (1994, p. 239); Park (2020, p. 277)

- ^ Newell & Avery (1994, pp. 114–115); Park (2020, pp. 195–196)

- ^ Van Wagoner (1992, p. 53); Newell & Avery (1994, pp. 128–129)

- ^ Van Wagoner (1992, pp. 113–115).

- ^ Journal of Mormon History, Spring 2005, vol. 31, p. 70.

- ^ a b "What Happened to Joseph and Emma Smith's Children? – Joseph Smith Jr and Emma Hale Smith Historical Society". 2020-05-25. Retrieved 2023-05-17.

Other sources

- Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery, Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith (New York: Doubleday, 1984). ISBN 0-385-17166-8. 2nd edition. rev., Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

- Michael Hicks, Mormonism and Music: A History, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989; [Paperback Ed., 2003]).

- Dan Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, Vol. 4, (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002).

- Roger D. Launius, Joseph Smith III: Pragmatic Prophet, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

- Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, (New York: Knopf, 2005)

Sources

- Newell, Linda King; Avery, Valeen Tippetts (1984). Mormon Enigma – Emma Hale Smith (2nd ed.). Doubleday. ISBN 0385171668.

- Reeder, Jennifer (2021). First : the life and faith of Emma Smith. Salt Lake City, Utah. ISBN 978-1-62972-878-0. OCLC 1230256165.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Park, Benjamin E. (2020). Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier. New York, NY: Liveright. ISBN 978-1-324-09110-3.

- Bringhurst, Newell G.; Foster, Craig L., eds. (2010). The Persistence of Polygamy: Joseph Smith and the Origins of Mormon Polygamy. Independence, MO: John Whitmer Books. ISBN 978-1-934901-13-7.

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1971). No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-46967-4.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4270-4.

- Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1992). Mormon Polygamy: A History (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 978-0-941214-79-7.

- Newell, Linda King; Avery, Valeen Tippetts (1994). Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith (2nd ed.). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06291-4.

- Davenport, Stewart (2022). Sex and Sects: The Story of Mormon Polygamy, Shaker Celibacy, and Oneida Complex Marriage. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-4705-1.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (2017). A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women's Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-74212-4.

- Hill, Marvin S. (1989). Quest for Refuge: The Mormon Flight from American Pluralism. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 978-0-941214-70-4.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1994). The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-056-6.

- Remini, Robert V. (2002). Joseph Smith. Penguin Lives. New York, NY: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-670-03083-X.

External links

Media related to Emma Smith at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Emma Smith at Wikimedia Commons

- Mormon enigma: Emma Hale Smith, prophet's wife, "elect lady," polygamy's foe (typewritten book draft), L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Emma Hale Smith certificate, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Smith family legal instruments, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Testimony regarding Emma Smith Bidamon, Nauvoo, Illinois, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University