Crystal Cubism

Crystal Cubism (French: Cubisme cristal or Cubisme de cristal) is a distilled form of Cubism consistent with a shift, between 1915 and 1916, towards a strong emphasis on flat surface activity and large overlapping geometric planes. The primacy of the underlying geometric structure, rooted in the abstract, controls practically all of the elements of the artwork.[1]

This range of styles of painting and sculpture, especially significant between 1917 and 1920 (referred to alternatively as the Crystal Period, classical Cubism, pure Cubism, advanced Cubism, late Cubism, synthetic Cubism, or the second phase of Cubism), was practiced in varying degrees by a multitude of artists; particularly those under contract with the art dealer and collector Léonce Rosenberg—Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Henri Laurens, and Jacques Lipchitz most noticeably of all. The tightening of the compositions, the clarity and sense of order reflected in these works, led to its being referred to by the French poet and art critic Maurice Raynal as 'crystal' Cubism.[2] Considerations manifested by Cubists prior to the outset of World War I—such as the fourth dimension, dynamism of modern life, the occult, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration—had now been vacated, replaced by a purely formal frame of reference that proceeded from a cohesive stance toward art and life.

As post-war reconstruction began, so too did a series of exhibitions at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de L'Effort Moderne: order and the allegiance to the aesthetically pure remained the prevailing tendency. The collective phenomenon of Cubism once again—now in its advanced revisionist form—became part of a widely discussed development in French culture. Crystal Cubism was the culmination of a continuous narrowing of scope in the name of a return to order; based upon the observation of the artists relation to nature, rather than on the nature of reality itself.[3]

Crystal Cubism, and its associative rappel à l’ordre, has been linked with an inclination—by those who served the armed forces and by those who remained in the civilian sector—to escape the realities of the Great War, both during and directly following the conflict. The purifying of Cubism from 1914 through the mid-1920s, with its cohesive unity and voluntary constraints, has been linked to a much broader ideological transformation towards conservatism in both French society and French culture. In terms of the separation of culture and life, the Crystal Cubist period emerges as the most important in the history of Modernism.[1]

Background

Beginnings: Cézanne

Cubism, from its inception, stems from the dissatisfaction with the idea of form that had been in practice since the Renaissance.[4] This dissatisfaction had already been seen in the works of the Romanticist Eugène Delacroix, in the Realism of Gustave Courbet, in passing through the Symbolists, Les Nabis, the Impressionists and the Neo-Impressionists. Paul Cézanne was instrumental, as his work marked a shift from a more representational art form to one that was increasingly abstract, with a strong emphasis on the simplification of geometric structure. In a letter addressed to Émile Bernard dated 15 April 1904, Cézanne writes: "Interpret nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone; put everything in perspective, so that each side of an object, of a plane, recedes toward a central point."[5]

Cézanne was preoccupied by the means of rendering volume and space, surface variations (or modulations) with overlapped shifting planes. Increasingly in his later works, Cézanne achieves a greater freedom. His work became bolder, more arbitrary, more dynamic and increasingly nonrepresentational. As his color planes acquired greater formal independence, defined objects and structures began to lose their identity.[5]

The first phase

Artists at the forefront of the Parisian art scene at the outset of the 20th century would not fail to notice the tendencies toward abstraction inherent in the work of Cézanne, and ventured still further.[6] A reevaluation in their own work in relation to that of Cézanne had begun following a series of retrospective exhibitions of Cézanne's paintings held at the Salon d'Automne of 1904, the Salon d'Automne of 1905 and 1906, followed by two commemorative retrospectives after his death in 1907.[7] By 1907, representational form gave way to a new complexity; subject matter progressively became dominated by a network of interconnected geometric planes, the distinction between foreground and background no longer sharply delineated, and the depth of field limited.[8]

From the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition which officially introduced "Cubism" to the public as an organized group movement, and extending through 1913, the fine arts had evolved well beyond the teachings of Cézanne. Where before, the foundational pillars of academicism had been shaken, now they had been toppled.[4] "It was a total regeneration", writes Gleizes, "indicating the emergence of a wholly new cast of mind. Every season it appeared renewed, growing like a living body. Its enemies could, eventually, have forgiven it if only it had passed away, like a fashion; but they became even more violent when they realized that it was destined to live a life that would be longer than that of those painters who had been the first to assume the responsibility for it".[4] The evolution towards rectilinearity and simplified forms continued through 1909 with greater emphasis on clear geometric principles; visible in the works of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier and Robert Delaunay.[8][9][10]

Pre-war: analysis and synthesis

The Cubist method leading to 1912 has been considered 'analytical', entailing the decomposition of the subject matter (the study of things), while subsequently 'synthetic', built on geometric construction (free of such primary study). The terms Analytic Cubism and Synthetic Cubism originated through this distinction.[2] By 1913 Cubism had transformed itself considerably in the range of spatial effects.[2] At the 1913 Salon des Indépendants Jean Metzinger exhibited his monumental L'Oiseau bleu; Robert Delaunay L'équipe du Cardiff F.C.; Fernand Léger Le modèle nu dans l'atelier; Juan Gris L'Homme au Café; and Albert Gleizes Les Joueurs de football. At the 1913 Salon d'Automne, a salon in which the predominating tendency was Cubism, Metzinger exhibited En Canot; Gleizes Les Bâteaux de Pêche; and Roger de La Fresnaye La Conquête de l'Air.[4] In these works, more so than before, can be seen the importance of the geometric plane in the overall composition.[4]

Historically, the first phase of Cubism is identified as much by the inventions of Picasso and Braque (amongst the so-called Gallery Cubists) as it is with the common interests towards geometrical structure of Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay and Le Fauconnier (the Salon Cubists).[11] As Cubism would evolve pictorially, so too would the crystallization of its theoretical framework advance beyond the guidelines set out in the Cubist manifesto Du "Cubisme", written by Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger in 1912; though Du "Cubisme" would remain the clearest and most intelligible definition of Cubism.[9]

-

Jean Metzinger, 1912–1913, L'Oiseau bleu, (The Blue Bird), oil on canvas, 230 × 196 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Robert Delaunay, 1913, L'Équipe de Cardiff, oil on canvas, 326 × 208 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Fernand Léger, 1912–13, Nude Model in the Studio (Le modèle nu dans l'atelier), oil on burlap, 128.6 × 95.9 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

Juan Gris, 1912, Man in a Café, oil on canvas, 127.6 × 88.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Albert Gleizes, 1912–13, Les Joueurs de football (Football Players), oil on canvas, 225.4 × 183 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

-

Jean Metzinger, 1913, En Canot (Im Boot), oil on canvas, 146 × 114 cm, confiscated by the Nazis circa 1936, displayed at the Degenerate Art exhibition, and missing ever since.[12]

-

Albert Gleizes, 1913, Les Bateaux de pêche (Fischerboote), oil on canvas, 165 × 111 cm, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

-

Roger de La Fresnaye, 1913, The Conquest of the Air, oil on canvas, 235.9 × 195.6 cm, Museum of Modern Art

War years: 1914–1918

At the outset of the First World War many artists were mobilized: Metzinger, Gleizes, Braque, Léger, de La Fresnaye, and Duchamp-Villon. Despite the brutal interruption, each found the time to continue making art, sustaining differing types of Cubism. Yet they discovered a ubiquitous link between the Cubist syntax (beyond pre-war attitudes) and that of the anonymity and novelty of mechanized warfare. Cubism evolved as much a result of an evasion of the inconceivable atrocities of war as of nationalistic pressures. Along with the evasion came the need to diverge further and further away from the depiction of things. As the rift between art and life grew, so too came the burgeoning need for a process of distillation.[1]

This period of profound reflection contributed to the constitution of a new mindset; a prerequisite for fundamental change. The flat surface became the starting point for a revaluation of the fundamental principles of painting.[4] Rather than relying on the purely intellectual, the focus now was on the immediate experience of the senses, based on the idea according to Gleizes, that form, 'changing the directions of its movement, will change its dimensions' ["La forme, modifiant ses directions, modifiait ses dimensions"], while revealing the "basic elements" of painting, the "true, solid rules – rules which could be generally applied". It was Metzinger and Gris who, again according to Gleizes, "did more than anyone else to fix the basic elements... the first principles of the order that was being born".[4] "But Metzinger, clear-headed as a physicist, had already discovered those rudiments of construction without which nothing can be done."[4] Ultimately, it was Gleizes who would take the synthetic factor furthest of all.[1]

The many Cubist considerations manifested prior to World War I—such as the fourth dimension, dynamism of modern life, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration—had now been replaced by a formal reference frame which constituted the second phase of Cubism, based upon an elementary set of principles that formed a cohesive Cubist aesthetic.[2][13] This clarity and sense of order spread to almost all of the artists exhibiting at Léonce Rosenberg's gallery—including Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Laurens, Auguste Herbin, Joseph Csaky, Gino Severini and Pablo Picasso—leading to the descriptive term 'Crystal Cubism', coined by Maurice Raynal,[2] an early promoter of Cubism and continuous supporter during the war and post-war phase that followed.[14] Raynal had been associated with Cubists since 1910 via the milieu of Le Bateau-Lavoir.[15] Raynal, who would become one of the Cubists most authoritative and articulate proponents,[16] endorsed a wide range of Cubist activity and for those who produced it, but his highest esteem was directed toward two artists: Jean Metzinger, whose artistry Raynal equated with Renoir and who was 'perhaps the man who, in our epoch, knows best how to paint'. The other was Juan Gris, who was 'certainly the fiercest of the purists in the group'.[16]

In 1915, while serving on the front line, Raynal suffered a minor shrapnel wound to the knee from exploding enemy artillery fire, though the injury did not necessitate his evacuation.[17] Upon returning from the front line, Raynal served briefly as director for publications of Rosenberg's l'Effort moderne.[18][19] For Raynal, research into art was based on an eternal truth, rather than on the ideal, on reality, or on certitude. Certitude was nothing more than based on a relative belief, while truth was in agreement with fact. The only belief was in the veracity of philosophical and scientific truths.[20]

"Direct reference to observed reality" is present, but the emphasis is placed on the "self-sufficiency" of the artwork as objects unto themselves. The priority on "orderly qualities" and the "autonomous purity" of compositions are a prime concern, writes art historian Christopher Green.[2] Crystal Cubism also coincided with the emergence of a methodical framework of theoretical essays on the topic,[2] by Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Gino Severini, Pierre Reverdy, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and Maurice Raynal.[1]

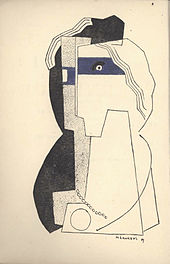

Metzinger

Even before Raynal coined the term Crystal Cubism, one critic by the name of Aloës Duarvel, writing in L'Elan, referred to Metzinger's entry exhibited at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune as 'jewellery' ("joaillerie").[21] Another critic, Aurel, writing in L'Homme Enchaîné about the same December 1915 exhibition described Metzinger's entry as "a very erudite divagation of horizon blue and old red of glory, in the name of which I forgive him" [une divagation fort érudite en bleu horizon et vieux rouge de gloire, au nom de quoi je lui pardonne].[22]

During the year 1916, Sunday discussions at the studio of Lipchitz, included Metzinger, Gris, Picasso, Diego Rivera, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Reverdy, André Salmon, Max Jacob, and Blaise Cendrars.[23]

In a letter written in Paris by Metzinger to Albert Gleizes in Barcelona during the war, dated 4 July 1916, he writes:

After two years of study I have succeeded in establishing the basis of this new perspective I have talked about so much. It is not the materialist perspective of Gris, nor the romantic perspective of Picasso. It is rather a metaphysical perspective—I take full responsibility for the word. You can't begin to imagine what I've found out since the beginning of the war, working outside painting but for painting. The geometry of the fourth space has no more secret for me. Previously I had only intuitions, now I have certainty. I have made a whole series of theorems on the laws of displacement [déplacement], of reversal [retournement] etc. I have read Schoute, Rieman (sic), Argand, Schlegel etc.

The actual result? A new harmony. Don't take this word harmony in its ordinary [banal] everyday sense, take it in its original [primitif] sense. Everything is number. The mind [esprit] hates what cannot be measured: it must be reduced and made comprehensible.

That is the secret. There in nothing more to it [pas de reste à l'opération]. Painting, sculpture, music, architecture, lasting art is never anything more than a mathematical expression of the relations that exist between the internal and the external, the self [le moi] and the world. (Metzinger, 4 July 1916)[23][24]

The 'new perspective' according to Daniel Robbins, "was a mathematical relationship between the ideas in his mind and the exterior world".[23] The 'fourth space' for Metzinger was the space of the mind.[23]

In a second letter to Gleizes, dated 26 July 1916, Metzinger writes:

If painting was an end in itself it would enter into the category of the minor arts which appeal only to physical pleasure... No. Painting is a language—and it has its syntax and its laws. To shake up that framework a bit to give more strength or life to what you want to say, that isn't just a right, it's a duty; but you must never lose sight of the End. The End, however, isn't the subject, nor the object, nor even the picture—the End, it is the idea. (Metzinger, 26 July 1916)[23]

Continuing, Metzinger mentions the differences between himself and Juan Gris:

Someone from whom I feel ever more distant is Juan Gris. I admire him but I cannot understand why he wears himself out with decomposing objects. Myself, I am advancing towards synthetic unity and I don't analyze any more. I take from things what seems to me to have meaning and be most suitable to express my thought. I want to be direct, like Voltaire. No more metaphors. Ah those stuffed tomatoes of all the St-Pol-Roux of painting.[23][24]

Some of the ideas expressed in these letters to Gleizes were reproduced in an article written by the writer, poet, and critique Paul Dermée, published in the magazine SIC in 1919,[25] but the existence of letters themselves remained unknown until the mid-1980s.[23]

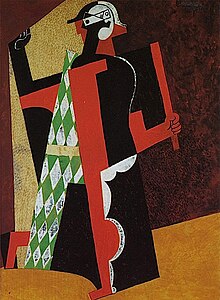

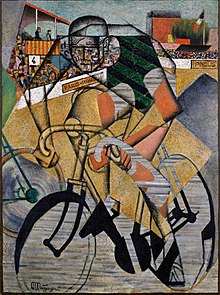

While Metzinger's process of distillation is already noticeable during the latter half of 1915, and conspicuously extending into early 1916, this shift is signaled in the works of Gris and Lipchitz from the latter half of 1916, and particularly between 1917 and 1918. Metzinger's radical geometrization of form as an underlying architectural basis for his 1915-16 compositions is already visible in his work circa 1912-13, in paintings such as Au Vélodrome (1912) and Le Fumeur (c.1913). Where before, the perception of depth had been greatly reduced, now, the depth of field was no greater than a bas-relief.[1]

Metzinger's evolution toward synthesis has its origins in the configuration of flat squares, trapezoidal and rectangular planes that overlap and interweave, a "new perspective" in accord with the "laws of displacement". In the case of Le Fumeur Metzinger filled in these simple shapes with gradations of color, wallpaper-like patterns and rhythmic curves. So too in Au Vélodrome. But the underlying armature upon which all is built is palpable. Vacating these non-essential features would lead Metzinger on a path towards Soldier at a Game of Chess (1914–15), and a host of other works created after the artist's demobilization as a medical orderly during the war, such as L'infirmière (The Nurse) location unknown, and Femme au miroir, private collection.

If the beauty of a painting solely depends on its pictorial qualities: only retaining certain elements, those that seem to suit our need for expression, then with these elements, building a new object, an object which we can adapt to the surface of the painting without subterfuge. If that object looks like something known, I take it increasingly for something of no use. For me it is enough for it to be "well done", to have a perfect accord between the parts and the whole. (Jean Metzinger, quoted in Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920)[26]

For Metzinger, the Crystal period was synonymous with a return to "a simple, robust art".[27] Crystal Cubism represented an opening up of possibilities. His belief was that technique should be simplified and that the "trickery" of chiaroscuro should abandoned, along with the "artifices of the palette".[27] He felt the need to do without the "multiplication of tints and detailing of forms without reason, by feeling":[27]

- "Feeling! It is like the expression of the old-school tragedian in acting! I want clear ideas, frank colors. 'No color, nothing but nuance', Verlaine used to say; but Verlaine is dead, and Homer is not afraid to handle color". (Metzinger)[27]

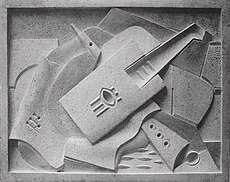

Gris

Juan Gris' late arrival on the Cubist scene (1912) saw him influenced by the leaders of the movement: Picasso, of the 'Gallery Cubists' and Metzinger of the 'Salon Cubists'.[28][29] His entry at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, Hommage à Pablo Picasso, was also an homage to Metzinger's Le goûter (Tea Time). Le goûter persuaded Gris of the importance of mathematics (numbers) in painting.[30]

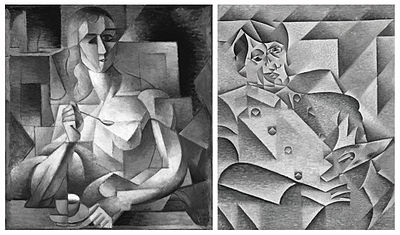

As art historian Peter Brooke points out, Gris started painting persistently in 1911 and first exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants (a painting entitled Hommage à Pablo Picasso). "He appears with two styles", writes Brooke, "In one of them a grid structure appears that is clearly reminiscent of the Goûter and of Metzinger's later work in 1912. In the other, the grid is still present but the lines are not stated and their continuity is broken".[31] Art historian Christopher Green writes that the "deformations of lines" allowed by mobile perspective in the head of Metzinger's Tea-time and Gleizes's Portrait of Jacques Nayral "have seemed tentative to historians of Cubism. In 1911, as the key area of likeness and unlikeness, they more than anything released the laughter." Green continues, "This was the wider context of Gris's decision at the Indépendants of 1912 to make his debut with a Homage to Pablo Picasso, which was a portrait, and to do so with a portrait that responded to Picasso's portraits of 1910 through the intermediary of Metzinger's Tea-time.[32] While Metzinger's distillation is noticeable during the latter half of 1915 and early 1916, this shift is signaled in the works of Gris and Lipchitz from the latter half of 1916, and particularly between 1917 and 1918.[1]

Kahnweiler dated the shift in style of Juan Gris to the summer and autumn of 1916, following the pointilliste paintings of early 1916;[11] in which Gris brought into practice Divisionist theory via the incorporation of colored dots into his Cubist pictures.[11] This timescale corresponds with the period after which Gris signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg, following a rally of support by Henri Laurens, Lipchitz and Metzinger.[33]

"Here is the man who has meditated on everything modern", writes Guillaume Apollinaire in his 1913 publication The Cubist Painters, Aesthetic Meditations, "here is the painter who paints to conceive only new structures, whose aim is to draw or paint nothing but materially pure forms". Apollinaire compares the work of Gris with the "scientific cubism" of Picasso... "Juan Gris is content with purity, scientifically conceived. The conceptions of Juan Gris are always pure, and from this purity parallels are sure to spring".[34][35] And spring they did. In 1916, drawing from black and white postcards representing works by Corot, Velázquez and Cézanne, Gris created a series of classical (traditionalist) Cubist figure paintings, employing a purified range of pictorial and structural features. These works set the tone for his quest of an ideal unity for the next five years.[11]

"These themes of pictorial architecture and the "constants" of tradition were consolidated and integrated", writes Green et al; "The inference was there to be drawn: to restore tradition was to restore not only an old subject-matter in new terms, but to find the unchanging principles of structure in painting. Cohesion in space (composition) and cohesion in time (Corot in Gris) were presented as a single, fundamental truth".[11] Gris himself stressed the relativity and ephemerality of "truth" in his paintings (as a function of him) as in the world itself (as a function of society, culture and time); always susceptible to change.[11]

From 1915 to late 1916, Gris transited through three different styles of Cubism, writes Green: "starting with a solid extrapolation of the structures and materials of objects, moving into the placement of brilliant coloured dots drifting across flat signs for still-life objects, and culminating in a flattened 'chiaroscoro' realised in planar contrasts of a monochromatic palette".[11]

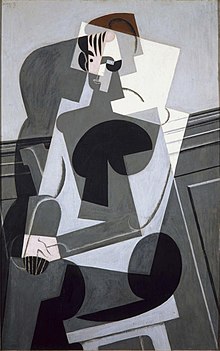

Gris's works from late 1916 through 1917, more so than before, exhibit a simplification of geometric structure, a blurring of the distinction between objects and setting, between subject matter and background. The oblique overlapping planar constructions, tending away from equilibrium, can best be seen in the artists Woman with Mandolin, after Corot (September 1916) and in its epilogue Portrait of Josette Gris (October 1916).[1]

The clear-cut underlying geometric framework of these works seemingly control the finer elements of the compositions; the constituent components, including the small planes of the faces, become part of the unified whole. Though Gris certainly had planned the representation of his chosen subject matter, the abstract armature serves as the starting point. The geometric structure of Juan Gris's Crystal period is already palpable in Still Life before an Open Window, Place Ravignan (June 1915). The overlapping elemental planar structure of the composition serves as a foundation to flatten the individual elements onto a unifying surface, foretelling the shape of things to come. In 1919 and particularly 1920, artists and critics began to write conspicuously about this 'synthetic' approach, and asserting its importance in the overall scheme of advanced Cubism.[1]

In April 1919, following exhibitions by Laurens, Metzinger, Léger and Braque, Gris present nearly fifty works at Rosenberg's Galerie de l'Effort moderne.[11] This first solo exhibition by Gris[36][37] coincided with his prominence among the Parisian avant-garde. Gris was presented to the public as one of the 'purest' and one of the most 'classical' of the leading Cubists.[38]

Gris claimed to manipulate flat abstract planar surfaces first, and only in subsequent stages of his painting process would he 'qualify' them so that the subject-matter became readable. He worked 'deductively' on the global concept first, then consecrated on the perceptive details. Gris referred to this technique as 'synthetic', in contradistinction from the process of 'analysis' intrinsic to his earlier works.[38]

Gris's open window series of 1921–22 appears to be a response to Picasso's open windows of 1919, painted in St. Raphael.[11] By May 1927, the date of his death, Gris had been considered the leader of the second phase of Cubism (the Crystal period).[11]

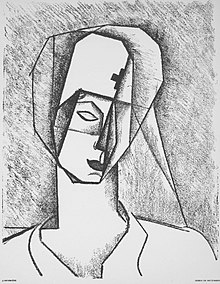

Picasso

While Metzinger and Gris were painting in advanced geometric form during the second phase of Cubism, Picasso worked on several projects simultaneously. Between 1915 and 1917, he began a series of paintings depicting highly geometric and minimalist Cubist objects, consisting of either a pipe, a guitar or a glass, with an occasional element of collage. "Hard-edged square-cut diamonds", notes art historian John Richardson, "these gems do not always have upside or downside".[39][40] "We need a new name to designate them," wrote Picasso to Gertrude Stein: Maurice Raynal suggested "Crystal Cubism".[39][41] These "little gems" may have been produced by Picasso in response to critics who had claimed his defection from the movement, through his experimentation with classicism within the so-called return to order.[1][39]

-

Pablo Picasso, 1914, Composition à la guitare, lithograph, 47.5 × 36 cm

-

Pablo Picasso, 1914–15, Nature morte au compotier (Still Life with Compote and Glass), oil on canvas, 63.5 × 78.7 cm (25 × 31 in), Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

-

Pablo Picasso, 1916, L'anis del mono (Bottle of Anis del Mono), oil on canvas, 46 x 54.6 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan

-

Pablo Picasso, 1916, Still-life with Door, Guitar and Bottles, oil on canvas, 152.4 × 205.7 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

-

Pablo Picasso, 1916, Guitare, clarinette et bouteille sur une table (Guitar, Clarinet, and Bottle on a Pedestal Table)

-

Pablo Picasso, 1918, Arlequin jouant de la guitare (Harlequin)

-

Pablo Picasso, 1919, La table devant la fenêtre (The Table in front of the Window), oil on canvas, collection Paul Rosenberg

-

Pablo Picasso, 1921, Nous autres musiciens (Three Musicians), oil on canvas, 204.5 × 188.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

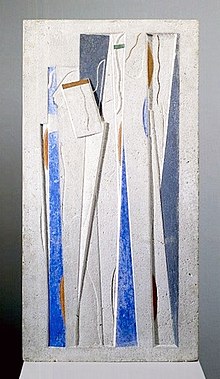

Csaky, Laurens and Lipchitz

Joseph Csaky enlisted as a volunteer in the French army in 1914, fighting alongside French soldiers during World War I, and remained for the duration. Returning to Paris in 1918, Csaky began a series of Cubist sculptures derived in part from a machine-like aesthetic; streamlined with geometric and mechanical affinities. By this time Csaky's artistic vocabulary had evolved considerably from his pre-war Cubism: it was distinctly mature, showing a new, refined sculptural quality. Few works of early modern sculpture are comparable to the work Csaky produced in the years directly succeeding World War I. These were nonrepresentational freely-standing objects, i.e., abstract three-dimensional constructions combining organic and geometric elements. "Csaky derived from nature forms which were in concordance with his passion for architecture, simple, pure, and psychologically convincing." (Maurice Raynal, 1929)[42]

The scholar Edith Balas writes of Csaky's sculpture following the war years:

"Csáky, more than anyone else working in sculpture, took Pierre Reverdy's theoretical writings on art and cubist doctrine to heart. "Cubism is an eminently plastic art; but an art of creation, not of reproduction and interpretation." The artist was to take no more than "elements" from the external world, and intuitively arrive at the "idea" of objects made up of what for him constant in value. Objects were not to be analyzed; neither were the experiences they evoked. They were to be re-created in the mind, and thereby purified. By some unexplained miracle the "pure" forms of the mind, an entirely autonomous vocabulary, of (usual geometric) forms, would make contact with the external world." (Balas, 1998, p. 27)[42]

These 1919 works (e.g., Cones and Spheres, Abstract Sculpture, Balas, pp. 30–41)[42] are made of juxtaposing sequences of rhythmic geometric forms, where light and shadow, mass and the void, play a key role. Though almost entirely abstract, they allude, occasionally, to the structure of the human body or modern machines, but the semblance functions only as "elements" (Reverdy) and are deprived of descriptive narrative. Csaky's polychrome reliefs of the early 1920s display an affinity with Purism—an extreme form of the Cubism aesthetic developing at the time—in their rigorous economy of architectonic symbols and the use of crystalline geometric structures.[42]

Csaky's Deux figures, 1920, Kröller-Müller Museum, employs broad planar surfaces accented by descriptive linear elements comparable to Georges Valmier's work of the following year (Figure 1921).[43] Csaky's influences were drawn more from the art of ancient Egypt rather than from French Neoclassicism.[1]

With this intense flurry of activity, Csaky was taken on by Léonce Rosenberg, and exhibited regularly at the Galerie l'Effort Moderne. By 1920 Rosenberg was the sponsor, dealer and publisher of Piet Mondrian, Léger, Lipchitz and Csaky. He had just published Le Néo-Plasticisme—a collection of writings by Mondrian—and Theo van Doesburg's Classique-Baroque-Moderne. Csaky's showed a series of works at Rosenberg's gallery in December 1920.[42]

For the following three years, Rosenberg purchased Csaky's entire artistic production. In 1921 Rosenberg organized an exhibit titled Les maîtres du Cubisme, a group show that featured works by Csaky, Gleizes, Metzinger, Mondrian, Gris, Léger, Picasso, Laurens, Braque, Herbin, Severini, Valmier, Ozenfant and Survage.[42]

Csaky's works of the early 1920s reflect a distinct form of Crystal Cubism, and were produced in a wide variety of materials, including marble, onyx and rock crystal. They reflect a collective spirit of the time, "a puritanical denial of sensuousness that reduced the cubist vocabulary to rectangles, verticals, horizontals," writes Balas, "a Spartan alliance of discipline and strength" to which Csaky adhered in his Tower Figures. "In their aesthetic order, lucidity, classical precision, emotional neutrality, and remoteness from visible reality, they should be considered stylistically and historically as belonging to the De Stijl movement." (Balas, 1998)[42]

Jacques Lipchitz recounted a meeting during the First World War with the poet and writer close to the Abbaye de Créteil, Jules Romains:

I remember in 1915 when I was deeply involved in cubist sculpture but was still in many ways not certain of what I was doing, I had a visit from the writer Jules Romains, and he asked me what I was trying to do. I answered, "I would like to make an art as pure as a crystal." And he answered in a slightly mocking way, "What do you know about crystals?" At first I was upset by this remark and his attitude, but then, as I began to think about it, I realized that I knew nothing about crystals except that they were a form of inorganic life and that this was not what I wanted to make.[44]

Both Lipchitz and Henri Laurens—late adherents to Cubist sculpture, following Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky, Umberto Boccioni, Otto Gutfreund and Picasso—began production in late 1914, and 1915 (respectively), taking Cubist paintings of 1913-14 as a starting point.[46] Both Lipchitz and Laurens retained highly figurative and legible components in their works leading up to 1915-16, after which naturalist and descriptive elements were muted, dominated by a synthetic style of Cubism under the influence of Picasso and Gris.[46]

Between 1916 and 1918 Lipchitz and Laurens developed a breed of advanced wartime Cubism (primarily in sculpture) that represented a process of purification. With observed reality no longer the basis for the depiction of subject, model or motif, Lipchitz and Laurens created works that excluded any starting point, based predominantly on the imagination, and continued to do so during the transition from war to peace.[46]

In December 1918 Laurens, a close friend of both Picasso and Braque, inaugurated the series of Cubist exhibitions at L'Effort Moderne (Lipchitz showed in 1920), by which time his works had wholly approached the Cubist retour à l'ordre. Rather than descriptive, these works were rooted in geometric abstraction; a species of architectural, polychromed multimedia Cubist constructions.[1]

Criticism

From its first public exhibition in 1911, art critic Louis Vauxcelles had voiced his contempt for Cubism. In June 1918, Vauxcelles, writing under the pseudonym Pinturrichio, continued his attack:[47]

Integral Cubism is crumbling, vanishing, evaporating. Defections, every day, reach the headquarters of pure painting. Soon Metzinger will be the last of his species, representative of an abandoned doctrine. "And if one shall remain, he'll whisper painfully, I'll be the one". (Vauxcelles, 1918)[47]

The following month, Vauxcelles forecast the final demise of Cubism by the fall of 1918.[48] With the fall came the end of the war, and in December, a series of exhibitions at Galerie l'Effort Moderne of Cubist works demonstrated that Cubism was still alive.[1]

Defections by Diego Rivera and André Favory from the Cubist circle, cited by Pinturrichio, proved to be insufficient grounds upon which to base his prediction. Vauxcelles even went as far as organizing a small exhibition at the galerie Blot (late 1918) of artists that appeared to be anti-Cubist; Lhote, Rivera and Favory among them. Allies in Vauxcelles ongoing battle against Cubism included Jean-Gabriel Lemoine (L'Intransigeant), Roland Chavenon (L'Information), Gustave Kahn (L'Heure), and Waldemar George (Jerzy Waldemar Jarocinski), who would soon become one of the leading post-war supporters of Cubism.[1]

Inversely, once a steadfast supporter of Cubism, André Salmon in 1917-18 predicted too its demise; claiming it to have been merely a phase leading to a new art-form more closely attuned with nature. Two more former advocates of Cubism had also defected, Roger Allard and Blaise Cendrars, joining the ranks of Vauxcelles in frontline attacks on Cubism. Allard reproached the visible distancing of Cubism from the dynamism and diversity of lived experience toward a universe of purified objects. Similarly, Cendrars wrote in an article published May 1919 "The formulae of the Cubists' are becoming too narrow, and can no longer embrace the personality of the painters".[1][49]

Counter attacks

The poet and theorist Pierre Reverdy had surpassed all rivals in his attacks on the anti-Cubist campaign between 1918 and 1919. He had been in close contact with the Cubists prior to the war, and in 1917 joined forces with two other poets who shared his points of view: Paul Dermée and Vicente Huidobro. In March of the same year Reverdy edited Nord-Sud.[50] The title of the magazine was inspired by the Paris Métro line that extended from Montmartre to Montparnasse, linking these two focal points of artistic creativity.[51] Reverdy began this project towards the end of 1916, with an art world still under the pressures of war, to show the parallels between the poetic theories of Guillaume Apollinaire of Max Jacob and himself in marking the burgeoning of a new era for poetry and artistic reflection. In Nord-Sud Reverdy, with the help of Dermée and Georges Braque, exposed his literary theories, and outlined a coherent theoretical stance on the latest developments in Cubism.[52] His treatise On Cubism, published in the first issue of Nord-Sud,[53] did so perhaps most influentially.[1][54] With his characteristic preference for offense rather than defense, Reverdy launched an attack against Vauxcelles' anti-Cubist crusade:

How many times has it been said that the art movement called Cubism is extinguished? Each time that a purge occurs the critics of the other side, who ask only that their desires be taken as facts, shout defection and howl for its death. This is nothing basically but a ruse, because Pinturrichichio [sic], of the Carnet de la Semaine and the others know very well that the serious artists of this group are extremely happy to see go... those opportunists who have taken over creations the significance of which they do not even comprehend, and were attracted only by the love of buzz and personal interest. It was predictable that these unrecommendable and compromising people would renounce their endeavors sooner or later. (Reverdy, 1918)[1][54]

Another vigorous supporter of Cubism was the art dealer and collector Léonce Rosenberg. By the end of 1918—filling in the vacuum left in the wake of D.-H. Kahnweiler's imposed exile—Rosenberg purchased works by almost all of the Cubists. His defense of Cubism would prove to be longer-lasting and wider-ranging than Reverdy's. His first tactical maneuver was to address a letter to Le Carnet de la Semaine denying the chimerical claim made by Vauxcelles that both Picasso and Gris had defected. Much more poignant and difficult to combat, however, was his second tactical maneuver: a succession of prominent Cubist exhibitions held at the Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, in Rosenber's Hôtel particulier, 19, rue de la Baume, located in the elegant and stylishly fashionable 8th arrondissement of Paris.[1]

This series of large exhibitions—including works created between 1914 and 1918 by almost all the major Cubists—began 18 December with Cubist sculptures by Henri Laurens, followed in January 1919 with an exhibition of Cubist paintings by Jean Metzinger, Fernand Léger in February, Georges Braque in March, Juan Gris April, Gino Severini May, and Pablo Picasso in June, marking the climax of the campaign. This well-orchestrated program showed that Cubism was still very much alive,[11] and it would remain so for at least a half-decade. Missing from this sequence of exhibitions were Jacques Lipchitz (who would exhibit in 1920), and those who had left France during the Great War: Robert Delaunay and Albert Gleizes most obviously. Nonetheless, according to Christopher Green, "this was an astonishingly complete demonstration that Cubism had not only continued between 1914 and 1917, having survived the war, but was still developing in 1918 and 1919 in its "new collective form" marked by "intellectual rigor". In the face of such a display of vigour, it really was difficult to maintain convincingly that Cubism was even close to extinction".[1]

-

Auguste Herbin, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, March 1918

-

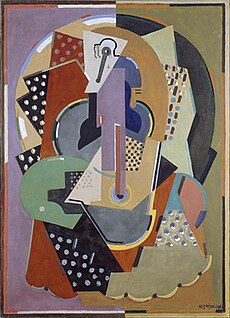

Jean Metzinger, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, January 1919

-

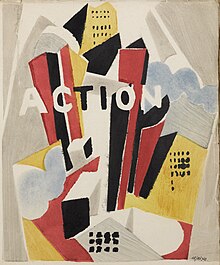

Fernand Léger, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, February 1919

-

Georges Braque, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, March 1919

-

Juan Gris, Galerie L'Effort Moderne, April 1919

-

Léopold Survage, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, November 1920

-

Joseph Csaky, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, December 1920

-

Georges Valmier, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, January 1921

Cubism has not ended, in humanizing itself it holds its promises. (Jean Metzinger, November 1923)[55]

Towards the crystal

Further evidence to bolster the prediction made by Vauxcelles could have been found in a small exhibition at the Galerie Thomas (in a space owned by a sister of Paul Poiret, Germaine Bongard). The first exhibition of Purist Art opened on 21 December 1918, with works by Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (later called Le Corbusier), who claimed to be successors of pre-war Cubism.[1][56] The beginnings of a Purist manifesto in book-form had been published to coincided with the exhibition, titled Après le cubisme (After Cubism):[57]

The War over, everything organizes, everything is clarified and purified; factories rise, already nothing remains as it was before the War: the great Competition has tested everything and everyone, it has gotten rid of the aging methods and imposed in their place others that the struggle has proven their betters... toward rigor, toward precision, toward the best utilization of forces and materials, with the least waste, in sum a tendency toward purity.[58]

Ozenfant and Jeanneret felt that Cubism had become too decorative,[59] practiced by so many individuals that it lacked unity, it had become too fashionable. Their clarity of subject matter (more figurative, less abstract than the Cubists) had been welcomed by members of the anti-Cubist camp. They showed works that were a direct result of observation; perspectival space only slightly distorted. Ozenfant and Jeanneret, like Lhote, remained faithful to the Cubist idiom that form should not be abandoned. Some of the works exhibited related directly to the Cubism practiced during the war (such as Ozenfant's Bottle, Pipe and Books, 1918), with flattened planar structures and varying degrees of multiple perspective.[1]

For Ozenfant and Jeanneret only Crystal Cubism had conserved the geometric rigor of the early Cubist revolution.[59][60] In 1915, in collaboration with Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire, Ozenfant founded the magazine L'Élan, which he edited until late 1916.[61][62][63] In 1917 he met Jeanneret, with whom he would join forces between 1918 and 1925 on a venture called Purism: a variation of Cubism in both painting and architecture.[64]

In collaboration with the pro-Cubist writer, poet, and critique Paul Dermée, Ozenfant and Jeanneret founded the avant-garde journal L'Esprit Nouveau, published from 1920 to 1925. In the last issue, Jeanneret, under the pseudonym Paul Boulard, writes of how the laws of nature were manifested in the shape of crystals; the properties of which were hermetically coherent, both interiorly and exteriorly. In La peinture moderne, under the title Vers le crystal, Ozenfant and Jeanneret liken the properties of crystals with the true Cubist, whose œuvre tends toward the crystal.[60][65]

Certain Cubists have created paintings that can be said to tend toward the perfection of the crystal. These works seem to approach our current needs. The crystal is, in nature, a phenomenon that affects us most because it clearly shows the path to geometric organization. Nature sometimes shows us how forms are built through a reciprocal interplay of internal and external forces ... following the theoretical forms of geometry; and man delights in these arrangements because he finds in them justification for his abstract conceptions of geometry: the spirit of man and nature find a factor of common ground, in the crystal. ... In true Cubism, there something organic that proceeds from the inside to the outside. ... The universality of the work depends on its plastic purity. (Ozenfant and Jeanneret, 1923–25)[59]

A second Purist exhibition was held at the Galerie Druet, Paris, in 1921. In 1924 Ozenfant opened a free studio in Paris with Fernand Léger, where he taught with Aleksandra Ekster and Marie Laurencin.[66] Ozenfant and Le Corbusier wrote La Peinture moderne in 1925.[60]

In final issue of L'élan, published December 1916, Ozenfant writes: "Le Cubisme est un movement de purism" (Cubism is a movement of purism).[67]

And in La peinture moderne, 1923–25, with Cubism visibly still alive and in highly crystalline form, Ozenfant and Jeanneret write:

We see the real cubists continue their work, imperturbable; they are also seen to continue their influence on spirits. ... They will arrive more or less strongly depending on the oscillations of their nature, their tenacity or their concessions and analysis [tâtonnement] that are characteristic of artistic creation, to search for a state of clarification, condensation, firmness, intensity, synthesis; they will arrive at a true virtuosity of the game of shapes and colors, as well as a highly developed science of the composition. Overall and despite the personal coefficients, one can discern a tendency towards what might be imaged in saying: tendency toward the crystal.[60]

The Crystal Cubists embraced the stability of everyday life, the enduring and the pure, but too the classical, with all that it signified respecting art and ideal. Order and clarity, right to the core of its Latin roots, was a dominant factor within the circle of Rosenberg's L'Effort moderne. While Lhote, Rivera, Ozenfant and Le Corbusier attempted to attain a compromise between the abstract and nature in their search for another Cubism, all of the Cubists shared common goals. The first, writes Green: "that art should not be concerned with the description of nature. ... The rejection of Naturalism was intimately bound up with the second basic principle shared by them all: that the work of art, being not an interpretation of anything else, was something in its own right with its own laws". These same sentiments observable from the outset of Cubism were now essential and prevailing to an extent never before seen. There was a third principle that followed from the former that came to light during the Crystal period, again according to Green: "the principle that nature should be approached as no more than the supplier of 'elements' to be pictorially or sculpturally developed and then freely manipulated according to the laws of the medium alone".[1]

Gleizes

Albert Gleizes had been in New York, Bermuda and Barcelona following a short stint serving the military at the fortress city of Toul, late 1914 early 1915.[9] His arrival in Paris after his self-imposed exile saw the new style already underway. Yet independently, Gleizes had been working in a similar direction as early as 1914–15: Portrait of an Army Doctor (Portrait d'un médecin militaire), 1914–15 (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum);[68] Musician (Florent Schmitt), 1915 (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum);[69] and with a much more ambitious subject matter: Le Port de New York, 1917 (Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum).[70][71]

Gleizes' mobilization was not a major obstacle to his production of artwork, though, working primarily on small scale, he did produce one relatively large piece: Portrait of an Army Doctor.[72] An admirer of his work, his commanding officer—the regimental surgeon portrayed by Gleizes in this painting—made arrangements so that Gleizes could continue to paint while mobilized at Toul.[73] This work, a precursor to Crystal Cubism, consists of broad, overlapping planes of brilliant color, dynamically intersecting vertical, diagonal, horizontal lines coupled with circular movements.[73][74] These two works, according to Gleizes, represented a break from 'Cubism of analysis', from the representation of volume of the first period of Cubism. He had now undertaken a path that lead to 'synthesis', with its starting point in 'unity'.[72][75]

This unity, and the highly crystalline geometricized materialization consisting of superimposed constituent planes of Crystal Cubism would ultimately be described by Gleizes, in La Peinture et ses lois (1922–23), as 'simultaneous movements of translation and rotation of the plane'.[71][72] The synthetic factor was ultimately taken furthest of all from within the Cubists by Gleizes.[1]

Gleizes believed that the Crystal Cubists—specifically Metzinger and Gris—had found the principles on which an essentially non-representational art could be built. He felt that the earlier abstract works of artists such as František Kupka and Henry Valensi, lacked a solid foundation.[76]

In his 1920 publication, Du Cubisme et les moyens de le comprendre, Gleizes explained that Cubism was now at a stage of development in which fundamental principles could be deduced from particular facts, applicable to a defined class of phenomena, drawn and taught to students. These basic theoretical postulates could be as productive for future developments of the fine arts as the mathematically based principles of three-dimensional perspective had been since the Renaissance.[77]

Painting and its Laws

Albert Gleizes undertook the task of writing the characterizations of these principles in Painting and its Laws (La Peinture et ses lois), published by gallery owner Jacques Povolozky in the journal La Vie des lettres et des arts, 1922-3, and as a book in 1924.[72][78][79]

In La Peinture et ses lois Gleizes deduces the fundamental laws of painting from the picture plane, its proportions, the movement of the human eye and the physical laws. This theory, subsequently referred to as translation-rotation, "ranks with the writings of Mondrian and Malevich", writes art historian Daniel Robbins, "as one of the most thorough expositions of the principles of abstract art, which in his case entailed the rejection not only of representation but also of geometric forms".[74]

One of Gleizes's primary objectives was to answer the questions: How will the planar surface be animated, and by what logical method, independent of the artists fantaisie, can it be attained?[80]

The approach:

Gleizes bases these laws both on truisms inherent throughout the history of art, and especially on his own experience since 1912, such as: "The primary goal of art has never been exterior imitation" (p. 31); "Artworks come from emotion... the product of individual sensibility and taste" (p. 42); "The artist is always in a state of emotion, sentimental exaltation [ivresse]" (p. 43); "The painting in which the idea of abstract creation is realized is no longer an anecdote, but a concrete fact" (p. 56); "Creating a painted artwork is not the emission of an opinion" (p. 59); "The plastic dynamism will be born out of rhythmic relations between objects... establishing novel plastic liaisons between purely objective elements that compose the painting" (p. 22).[79][81]

Continuing, Gleizes states that the 'reality' of a painting is not that of a mirror, but of the object... issue of imminent logic (p. 62). "The subject-pretext tending toward numeration, inscribed following the nature of the plane, attains a tangent intersections between known images of the natural world and unknown images that reside within intuition" (p. 63).[79][80]

Defining the laws:

Rhythm and space are for Gleizes the two vital conditions. Rhythm is a consequence of the continuity of certain phenomena, variable or invariable, following from mathematical relations. Space is a conception of the human psyche that follows from quantitative comparisons (pp. 35, 38, 51). This mechanism is the foundation for artistic expression. It is therefore both a philosophical and scientific synthesis. For Gleizes, Cubism was a means to arrive not only at a new mode of expression but above all a new way of thinking. This was, according to art historian Pierre Alibert, the foundation of both a new species of painting and an alternative relationship with the world; hence another principle of civilization.[79][80]

The problem set out by Gleizes was to replace anecdote as a starting point for the work of art, by the sole means of using the elements of the painting itself: line, form and color.[79][80]

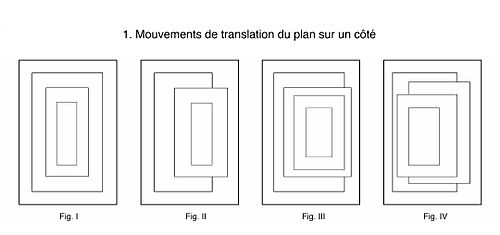

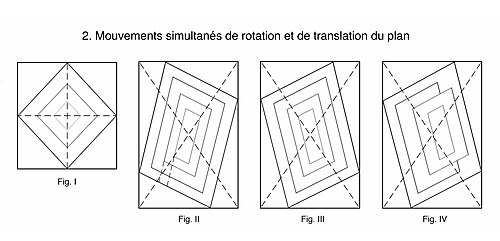

Beginning with a central rectangle, taken as an example of elementary form, Gleizes points out two mechanical ways of juxtaposing form to create a painting: (1) either by reproducing the initial form (employing various symmetries such as reflectional, rotational or translational), or by modifying (or not) its dimensions.[79] (2) By displacement of the initial form; pivoting around an imaginary axis in one direction or another.[79][80]

The choice of position (through translation and/or rotation), though based on the inspiration of the artist, is no longer attributed to the anecdotal. An objective and rigorous method, independent of the painter, replaces emotion or sensibility in the determination the placement of form, that is through translation and rotation.[79][80]

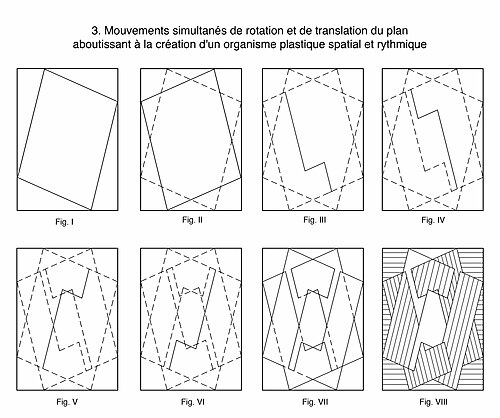

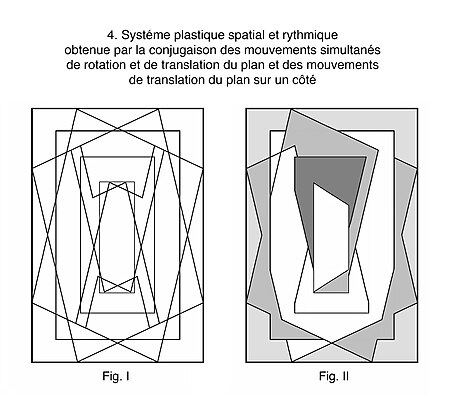

Schematic illustrations:

Space and rhythm, according to Gleizes, are perceptible by the extent of movement (displacement) of planar surfaces. These elemental transformations modify the position and importance of the initial plane, whether they converge or diverge ('recede' or 'advance') from the eye, creating a series of new and separate spatial planes appreciable physiologically by the observer.[79][80]

Another movement is added to the first movement of translation of the plane to one side: Rotation of the plane. Fig. I shows the resulting formation that follows from simultaneous movements of rotation and translation of the initial plane produced on the axis. Fig II and Fig. III represent the simultaneous movements of rotation and translation of the rectangle, inclined to the right and to the left. The axis point at which movement is realized is established by the observer. Fig. IV represents the simultaneous movements of rotation and translation of the rectangle plane, with the position of the eye of the observed displaced left of the axis. Displacement toward the right (though not represented) is straightforward enough to imagine.[79][80]

With these figures Gleizes attempts to present, under the most simple conditions possible (simultaneous movements of rotation and translation of the plane), the creation of a spatial and rhythmic organism (Fig. VIII), with practically no initiative taken on the part of the artist who controls the evolutionary process. The planar surfaces of Fig. VIII are filled with hatching espousing the 'direction' of the planes. What emerges in the inert plane, according to Gleizes, through the movement followed by the eye of the observer, is "a visible imprint of successive stages of which the initial rhythmic cadence coordinated a succession of differing states". These successive stages permit the perception of space. The initial state, by consequence of the transformation, has become a spatial and rhythmic organism.[79][80]

Fig. I and Fig. II obtain mechanically, Gleizes writes; with minimal personal initiative, a "plastic spatial and rhythmic system", by the conjugation of simultaneous movements of rotation and translation of the plane and from the movements of translation of the plane to one side. The result is a spatial and rhythmic organism more complex than shown in Fig. VIII; demonstrating through mechanical, purely plastic means, the realization of a material universe independent of intentional intervention by the artist. This is sufficient to demonstrate, according to Gleizes, the possibilities of the plane to serve spatially and rhythmically by its own power.[79][80] [L'exposé hâtif de cette mécanique purement plastique aboutissant à la réalisation d'un univers matériel en dehors de l'intervention particulière intentionnelle, suffit à démontrer la possibilité du plan de signifier spatialement et rythmiquement par sa seule puissance].[79][80]

The end-product

Throughout the war, to Armistice of 11 November 1918 and the series of exhibitions at Galerie de L'Effort Moderne that followed, the rift between art and life—and the overt distillation that came with it—had become the canon of Cubist orthodoxy; and it would persist despite its antagonists through the 1920s:[1]

Order remained the keynote as post-war reconstruction commenced. It is not surprising, therefore, to find a continuity in the development of Cubist art as the transition was made from war to peace, an unbroken commitment to the Latin virtues along with an unbroken commitment to the aesthetically pure. The new Cubism that emerged, the Cubism of Picasso, Laurens, Gris, Metzinger and Lipchitz most obviously of all, has come to be known as "crystal Cubism". It was indeed the end-product of a progressive closing down of possibilities in the name of a "call to order". (Christopher Green, 1987, p. 37)[1][3]

More so than the pre-war Cubist period, the Crystal Cubist period has been described by Green as the most important in the history of Modernism:

In terms of a Modernist will to aesthetic isolation and of the broad theme of the separation of culture and society, it is actually Cubism after 1914 that emerges as most important to the history of Modernism, and especially... Cubism between around 1916 and around 1924... Only after 1914 did Cubism come almost exclusively to be identified with a single-minded insistence on the isolation of the art-object in a special category with its own laws and its own experience to offer, a category considered above life. It is Cubism in this later period that has most to tell anyone concerned with the problems of Modernism and post-modernism now, because it was only then that issues emerged with real clarity in and around Cubism which are closely comparable with those that emerged in and around Anglo-American Modernism in the sixties and after. (Green, 1987, Introduction, p. 1)[1]

Art historian Peter Brooke has commented on Crystal Cubism, and more generally on the Salon Cubists:

- "A general history of Salon Cubism, however, still needs to be written, a history that could be extended to include the wonderful collective phenomenon which Christopher Green has called 'Crystal Cubism' — the highly structured work of the Cubist painters... who remained in Paris during the war, most notably Metzinger and Gris. An opening up of this early Cubism in all its intellectual fullness would... reveal it as being not only the most radical movement in painting of the past century but, still, the most rich in possibilities for the future". (Peter Brooke, 2000)[82]

Artists

List of artists including those associated with Crystal Cubism to varying degrees between 1914 and the mid-1920s:[1]

- Alexander Archipenko

- María Blanchard

- Georges Braque

- Joseph Csaky

- Theo van Doesburg

- Roger de La Fresnaye

- Albert Gleizes

- Juan Gris

- Henri Hayden

- Auguste Herbin

- Henri Laurens

- Fernand Léger

- André Lhote

- Jacques Lipchitz

- Louis Marcoussis

- Jean Metzinger

- Piet Mondrian

- Pablo Picasso

- Diego Rivera

- Gino Severini

- Léopold Survage

- Georges Valmier

- Jacques Villon

Related works

These works, or works by these artists created during the same period, according to Christopher Green, are associated with Crystal Cubism, or were precursors in varying degrees to the style.[1]

-

Albert Gleizes, 1914, Woman with animals (La dame aux bêtes) Madame Raymond Duchamp-Villon, oil on canvas, 196.4 × 114.1 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

-

Juan Gris, September 1915, Jeu d'échecs (The Checkerboard), oil on canvas, 92.1 × 73 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

-

Jean Metzinger, 1916, Fruit and a Jug on a Table, oil and sand on canvas, 115.9 × 81 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Diego Rivera, after August 1916, Maternidad, Angelina y et niño Diego (Motherhood, Angelina and the Child Diego), oil on canvas, 134.5 × 88.5 cm, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City

-

Diego Rivera, 1916, Seated Woman (Woman with the Body of a Guitar), Frida Kahlo Museum

-

Juan Gris, 1917, Glass and Water Bottle, oil on panel, 54.8 × 32.7 cm, Ohara Museum of Art

-

María Blanchard, 1916–18, Still Life with Red Lamp, oil on canvas, 115.6 × 73 cm

-

Georges Braque, 1917, La Joueuse de mandoline, oil on canvas, 92 × 65 cm, Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art

-

Gino Severini, 1919, Bohémien Jouant de L'Accordéon (The Accordion Player), Museo del Novecento, Milan

-

Louis Marcoussis, 1919, Violon, bouteilles de Marc et cartes (Violin, Marc bottles and cards), gouache and watercolor over charcoal on paper, 45.8 × 24.5 cm

-

Alexander Archipenko, c.1920, Femme assise (Composition), 31.1 × 23.2 cm, gouache on paper

-

Albert Gleizes, 1920, Figure, gouache on canvas, 91.4 × 76.2 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, LACMA

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 13-47, 215

- ^ a b c d e f g Christopher Green, Late Cubism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ a b Thomas Vargish, Delo E. Mook, Inside Modernism: Relativity Theory, Cubism, Narrative, Yale University Press, 1999, p. 88, ISBN 0300076134

- ^ a b c d e f g h Albert Gleizes, L'Epopée, written in 1925, published in Le Rouge et le Noir, 1929. First published under the title Kubismus, 1928. English translation, The Epic, From immobile form to mobile form, by Peter Brooke

- ^ a b Erle Lora, Cézannes Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs, Foreword by Richard Shiff, University of California Press, 30 April 2006

- ^ Robert L. Herbert, 1968, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

- ^ Daniel Robbins, Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, 1985

- ^ a b Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes, Chronology of his life, 1881-1953

- ^ a b c Daniel Robbins, 1964, Albert Gleizes 1881 – 1953, A Retrospective Exhibition, Published by The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, in collaboration with Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

- ^ Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Du "Cubisme", Edition Figuière, Paris, 1912 (First English edition: Cubism, Unwin, London, 1913)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Christopher Green, Christian Derouet, Karin von Maur, Whitechapel Art Gallery, Juan Gris: Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 18 September – 29 November 1992: Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 18 December 1992 – 14 February 1993: Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, 6 March – 2 May 1993, Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 6, 22–60. ISBN 0300053746

- ^ Degenerate Art Database (Beschlagnahme Inventar, Entartete Kunst)

- ^ Green, Christopher; Musgrove, John (2003). "Cubism". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T020539. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Anna Jozefacka, Leonard A. Lauder, Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2015

- ^ David Cottington, Cubism in the Shadow of War: The Avant-garde and Politics in Paris 1905–1914, Yale University Press, 1998, p. 152, ISBN 0300075294

- ^ a b David Cottington, Cubism and Its Histories, Manchester University Press, 2004, pp. 151–153, ISBN 0719050049

- ^ L'Intransigeant, 9 July 1915, p. 2, National Library of France

- ^ Le Siècle, 8 April 1919, p. 3, National Library of France

- ^ Lectures, Le Nouveau Spectateur, No. 5, 10 July 1919, Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ^ Maurice Raynal, Quelques Intentions du Cubisme, éditions de L'Effort moderne, Paris, 1919

- ^ La Tombola artistique au profit des artistes polonais victimes de la guerre, 28 décembre 1915 au 15 janvier 1916, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 25, boulevard de la Madeleine, published in L'Elan, Number 8, January 1916

- ^ Échos, 1915 et la peinture, L'Homme Enchaîné, Paris, A3, No. 455, Saturday, 8 January 1916 (front page)

- ^ a b c d e f g Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, pp. 9–24

- ^ a b Peter Brooke, Higher Geometries, Precedents: Charles Henry and Peter Lenz, The subjective experience of space, Metzinger, Gris and Maurice Princet

- ^ Jean Metzinger, Une Esthétique, by Paul Dermée, SIC, Volume 4, Nos. 42, 43, March 30 and April 15, 1919, p. 336. Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University Library

- ^ Jean Metzinger, quoted in Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galerie Berès, 2006, p. 432. Reproduced in Christie's Paris, 2 May 2012, Lot 23 notes

- ^ a b c d Jean Metzinger, quoted in Maurice Raynal, Modern French Painters, Tudor Publishing Co., New York, 1934, p. 125 Archived 2015-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Golding, Visions of the Modern, University of California Press, 1994, ISBN 0520087925, p. 90

- ^ Picasso Posse: The Mona Lisa of Cubism, Michael Taylor, 2010, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1 Audio Stop 439, Podcast

- ^ John Richardson: A Life of Picasso, volume II, 1907–1917, The Painter of Modern Life, Jonathan Cape, London, 1996, p. 211

- ^ Peter Brooke, On "Cubism" in context, online since 2012

- ^ Christopher Green, Christian Derouet, Karin Von Maur, Juan Gris: [catalogue of the Exhibition], 1992, London and Otterlo, p. 160

- ^ Christian Derouet, Le cubisme "bleu horizon" ou le prix de la guerre. Correspondance de Juan Gris et de Léonce Rosenberg −1915-1917, Revue de l'Art, 1996, Vol. 113, Issue 113, pp. 40–64

- ^ Herschel Browning Chipp, Peter Selz, Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, University of California Press, 1968, pp. 221-248, ISBN 0-520-01450-2

- ^ The Little Review: Quarterly Journal of Art and Letters, Vol. 9, No. 2: Miscellany Number, Anderson, Margaret C. (editor), New York, 1922-12, Winter 1922, pp. 49-60

- ^ Juan Gris, Biography and Works, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

- ^ "Juan Gris, Collection Online, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum". Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ^ a b Christopher Green, Juan Gris, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ a b c John Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-1932, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Dec 24, 2008, pp. 77-78, ISBN 030749649X

- ^ Letter from Juan Gris to Maurice Raynal, 23 May 1917, Kahnweiler-Gris 1956, 18

- ^ Paul Morand, 1996, 19 May 1917, p. 143–144

- ^ a b c d e f g Edith Balas, 1998, Joseph Csaky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society

- ^ Georges Valmier, Figure, 1921, oil on canvas, 97.1 x 74.9 cm

- ^ Jacques Lipchitz, his life in sculpture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 30, No. 6 (Jun. - Jul., 1972), published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 285 (PDF)

- ^ Henri Laurens, in Celine Arnauld, Tournevire: Roman. Paris: Editions de "L'Esprit nouveau", 1919, p. 6. The International Dada Archive, The University of Iowa Libraries

- ^ a b c Douglas Cooper, "The Cubist Epoch", Phaidon Press Limited, 1970, in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-87587-041-4

- ^ a b Louis Vauxcelles (Pinturrichio), Le Carnet des ateliers, Le Carnet de la Semaine, 9 June 1918, p. 9

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles (Pinturrichio), De Profundis, Le Carnet de la Semaine, 28 July 1918, p. 6

- ^ Blaise Cendrars, Modernités, I, Quelle sera la nouvelle peinture?, La Rose Rouge, 3 May 1919. Reproduced in Aujourd'hui, Paris 1931, p. 98

- ^ Pierre Reverdy, Nord-Sud[permanent dead link], Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University Library

- ^ André Breton, Œuvres complètes No. 1, Gallimard, La Pléiade, 1988, note 3, p. 1075

- ^ Étienne-Alain Hubert, note au tome 1 des Œuvres complètes de Pierre Reverdy, Flammarion, page 1298

- ^ Pierre Reverdy, Sur le Cubisme, Nord-Sud, Volume 1, Number 1, 15 March 1917, pp. 5-7, Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University Library

- ^ a b Pierre Reverdy, Arts, Nord-Sud, Volume 2, Number 16, October 1918, p. 4, Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University Library

- ^ Jean Metzinger, Montparnasse, No. 27, November 1923

- ^ L'Intransigeant, 31 January 1921, p. 2, National Library of France

- ^ Amédée Ozenfant, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, Après le cubisme, Éditions des Commentaires, Paris, 1918

- ^ Amédée Ozenfant, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, Après le cubisme, quoted in Paul Mattick, Art In Its Time: Theories and Practices of Modern Aesthetics, Routledge, 2003, pp. 77-77, ISBN 1134554168

- ^ a b c Philip Speiser, Villa La Rocca, Fondation Le Corbusier, September 2009, p. 10 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Amédée Ozenfant, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, La peinture moderne, Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1925

- ^ L'élan, Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University Library[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Michelle Parker, L'Élan and Amédée Ozenfant: Art for Art's Sake?, DH and Literary Studies, 2011". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- ^ "Amédée Ozenfant, Solomon R. Guggenheim Collection". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ^ Ball, Susan (1981). Ozenfant and Purism: The Evolution of a style 1915–1930. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. p. 213.

- ^ Jan de Heer, The Architectonic Colour: Polychromy in the Purist Architecture of Le Corbusier 010 Publishers, 2009, p. 139, ISBN 906450671X

- ^ Judi Freeman, "Ozenfant, Amédée", Grove Art Online. Retrieved 26 November 2012

- ^ Amédée Ozenfant, Notes sur le cubisme, L'élan, Number 10, 1 December 1916, p. 3. Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University Library

- ^ Albert Gleizes, Portrait of an Army Doctor (Portrait d'un médecin militaire), 1914–15, oil on canvas, 119.8 x 95.1 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- ^ Albert Gleizes's, Musician (Florent Schmitt) (Un Musicien, Florent Schmitt), 1915, gouache on paper, 59.7 x 44.5 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- ^ Albert Gleizes, 1917, Le Port de New York, oil and sand on cardboard, 153 x 120 cm, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

- ^ a b Peter Brooke, Painting and Its Laws, Albert Gleizes, La peinture et ses lois, Ce qui devait sortir du Cubisme, Paris 1924

- ^ a b c d Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes: For and Against the Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0300089643

- ^ a b Albert Gleizes, Portrait of an Army Doctor, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- ^ a b Daniel Robbins, Albert Gleizes, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs: le Cubisme, 1908–1914, La guerre, Cahiers Albert Gleizes, Association des Amis d'Albert Gleizes, Lyon, 1957, p. 15. Reprinted, Ampuis, 1997, written during the First World War

- ^ July 09: Futurism at the Tate Modern: a review by Peter Brooke, From Cubism to Classicism, Painting and its Laws, From Cubism to Classicism by Gino Severini / Painting and its laws by Albert Gleizes, Francis Boutle, 2001 Archived 2015-06-08 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 1903427053

- ^ Peter Brooke, Victor Poznanski and the exhibition L'art d'aujourd'hui, 1925, Gleizes – ups and downs of Cubism

- ^ Albert Gleizes, Painting and Its Laws, summary by Peter Brooke

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pierre Alibert, Gleizes, Naissance et avenire du cubisme, Aubin-Visconti, Edition Dumas, Saint-Etienne, October 1982, ISBN 2-85529-000-7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Albert Gleizes, La Peinture et ses lois, Ce qui devait sortir du cubisme, La Vie des lettres et des arts, 1922-3, 1924 in book form

- ^ Albert Gleizes, Le Cubisme et la Tradition, Montjoie, Paris, 10 February 1913, p. 4. Reprinted as A Propos du Salon d'Automne, in Tradition et Cubisme, Paris, 1927. Gleizes outlines what he perceives as the 'decadence' inherent in the modern art.

- ^ Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes: For and Against the Twentieth Century, Introduction, p. xi, Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0300089643

External links

- Jean Metzinger, Culture.gouv.fr, le site du Ministère de la culture - base Mémoire

- Juan Gris, Culture.gouv.fr, le site du Ministère de la culture - base Mémoire

- Albert Gleizes, Culture.gouv.fr, le site du Ministère de la culture - base Mémoire

- Jean Metzinger, Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

- Jacques Lipchitz, Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

- Gino Severini, Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

- Juan Gris, Joconde, Portail des collections des musées de France

![Jean Metzinger, 1913, En Canot (Im Boot), oil on canvas, 146 × 114 cm, confiscated by the Nazis circa 1936, displayed at the Degenerate Art exhibition, and missing ever since.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/c/c5/Jean_Metzinger%2C_1913%2C_En_Canot%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_146_x_114_cm%2C_missing_or_destroyed.jpg/133px-Jean_Metzinger%2C_1913%2C_En_Canot%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_146_x_114_cm%2C_missing_or_destroyed.jpg)