Coronation riots

The coronation riots of October 1714 were a series of riots in southern and western England in protest against the coronation of the first Hanoverian king of Great Britain, George I.

Background

Upon the death in August 1714 of the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne, George Louis, Elector of Hanover, ascended the throne in accordance with the terms of the Act of Settlement 1701 that excluded Anne's half-brother James Francis Edward Stuart. After his arrival in Britain in September, George promptly dismissed the Tories from office and appointed a Whig-dominated government.

Riots

On 20 October, George was crowned at Westminster Abbey, but when his loyalists celebrated the coronation, they were disrupted by rioters in over twenty towns in the south and the west of England.[1] The rioters were supporters of High Church and Sacheverellite notions.[1] The Tory aristocrats and gentry absented themselves from the coronation and in some towns they arrived with their supporters to disrupt the Hanoverian proceedings.[2]

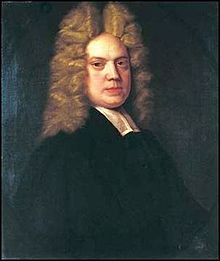

The celebrations of the coronation (balls, bonfires and drinking in taverns) were attacked by rioters who sacked their properties and assaulted the celebrants. Henry Sacheverell, who was on a 'progress' in the West Country, was mentioned by most of the rioters. At Bristol the crowd shouted, "Sacheverell and Ormond, and damn all foreigners!". In Taunton, they cried "Church and Dr. Sacheverell"; at Birmingham, "Kill the old Rogue [King George], Kill them all, Sacheverell for ever"; at Tewkesbury, "Sacheverell for ever, Down with the Roundheads"; at Shrewsbury, "High Church and Sacheverell for ever". In Dorchester and Nuneaton, Sacheverell's health was drunk.[3]

The High Church inspiration behind the rioters was also expressed in their attacks on Dissenters. In Bristol, a Dissenting meeting place was looted, with the murder of a Quaker, who had tried to persuade the mob to stop. A Dissenting meeting-house in Dorchester was "insulted", and there many expressions for local Tories among the rioters; in Canterbury they shouted "Hardress and Lee"; in Norwich, "Bene and Berney"; in Reading, "No Hanover, No Cadogan, but Calvert and Clarges".[3]

Along with those expressions of disaffection to the Hanoverian king were also expressions of Jacobite sentiments, despite that being a treasonable practice, according to the law. In Taunton, a Francis Sherry said on 19 October that "on the morrow he must take up Arms against the King". The Birmingham rioter John Hargrave said they must "pull down this King and Sett up a King of our own". In Dorchester, the rioters attempted to rescue an effigy of James Stuart that was to be burnt by Dissenters and asked: "Who dares disowne the Pretender?" In Tewkesbury l, the bargemen wished to drink to Sacheverell and the King but were criticised for putting Sacheverell first. The crowd replied that "it should be the King if they would have it so" but when asked which king, James or George, they attacked by them shouting, "Sacheverell for ever, Down with the Roundheads".[4][5]

In Bedford, the maypole was put in mourning. It was a Jacobite symbol symbolising the 'vegetation god' motif of the Stuart monarchy and was associated with the connection between May Day and Restoration Day.[6][7] The rule of the Puritans from 1649 to 1660 had outlawed the maypole, and it was not until the Restoration of 1660 that it was brought back: "Remarkably, this aspect of the Restoration was still remembered fifty years later, and was quickly adapted to imply that Hanoverian rule was no different from that of the ‘puritans’", according to Paul Monod.[6]

In Frome, Somerset, the rioters "dressed up an Idiot, called George, in a Fool's Coat, saying, Here's our George, where's —".[6][8]

The Anglican clergy mainly kept a low profile, but at Newton Abbot, the minister removed the bell-clappers so that the bells could not be rung in celebration of the coronation.[9]

Aftermath

The government did not trust local courts to prosecute the rioters and so tried to bring the rioters to London, but the scheme failed. Five rioters were brought to London from Taunton but were later released on bail. Seven Bristol rioters were to be tried by a Special Commission but it failed by prolonging the riot and was accompanied by an attack upon the Duke of Richmond at Chichester.[10] The rioters shouted at the judges: "No Jeffrey, no Western Assizes" and later: "A Cheverel, A Cheverel, and down with the Roundheads...up with the Cavaliers". A Tory merchant called William Hart (son of the Jacobite MP Richard Hart) was accused of being a ringleader of the rioters, but he escaped indictment. Other rioters were whipped, fined or imprisoned for three months.[11]

The general election of 1715, which was also accompanied by riots, produced a Whig majority in the House of Commons. In response to the riots, the new Whig majority passed the Riot Act to put down such disturbances.

Eleven days after the riots, Sacheverell published an open letter:

The Dissenters & their Friends have foolishly Endeavour'd to raise a Disturbance throughout the whole Kingdom by Trying in most Great Towns, on the Coronation Day to Burn Me in Effigie, to Inodiate my Person & Cause with the Populace: But if this Silly Stratagem has produc'd a quite Contrary Effect, & turn's upon the First Authors, & aggressors, and the People have Express'd their Resentment in any Culpable way, I hope it is not to be laid to my Charge, whose Name... they make Use of as the Shibboleth of the Party.[12]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Paul Kleber Monod, Jacobitism and the English People, 1688-1788 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 173.

- ^ Monod, pp. 173-174.

- ^ a b Monod, p. 174.

- ^ Monod, pp. 175-176.

- ^ Nicholas Rogers, ‘Riot and Popular Jacobitism in Early Hanoverian England’, in Eveline Cruickshanks (ed.), Ideology and Conspiracy: Aspects of Jacobitism, 1689-1759 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1982), p. 81.

- ^ a b c Monod, p. 176.

- ^ Rogers, p. 75.

- ^ Rogers, p. 71.

- ^ Monod, p. 177.

- ^ Monod, p. 178.

- ^ Monod, p. 179.

- ^ Monod, pp. 177-178.

References

- Paul Kleber Monod, Jacobitism and the English People. 1688-1788 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Nicholas Rogers, ‘Riot and Popular Jacobitism in Early Hanoverian England’, in Eveline Cruickshanks (ed.), Ideology and Conspiracy: Aspects of Jacobitism, 1689-1759 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1982), pp. 70–88.

Further reading

- An Account of the Riots, Tumults, and other Treasonable Practices; since His Majesty's Accession to the Throne (London, 1715).