Calcium-activated potassium channel

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2018) |

Calcium-activated potassium channels are potassium channels gated by calcium,[1] or that are structurally or phylogenetically related to calcium gated channels. They were first discovered in 1958 by Gardos[who?] who saw that calcium levels inside of a cell could affect the permeability of potassium through that cell membrane. Then in 1970, Meech was the first to observe that intracellular calcium could trigger potassium currents. In humans they are divided into three subtypes: large conductance or BK channels, which have very high conductance which range from 100 to 300 pS, intermediate conductance or IK channels, with intermediate conductance ranging from 25 to 100 pS, and small conductance or SK channels with small conductances from 2-25 pS.[2]

This family of ion channels is, for the most part, activated by intracellular Ca2+ and contains 8 members in the human genome. However, some of these channels (the KCa4 and KCa5 channels) are responsive instead to other intracellular ligands, such as Na+, Cl−, and pH. Furthermore, multiple members of family are both ligand and voltage activated, further complicating the description of this family. The KCa channel α subunits have six or seven transmembrane segments, similar to the KV channels but occasionally with an additional N-terminal transmembrane helix. The α subunits make homo- and hetero-tetrameric complexes. The calcium binding domain may be contained in the α subunit sequence, as in KCa1, or may be through an additional calcium binding protein such as calmodulin.

Structure

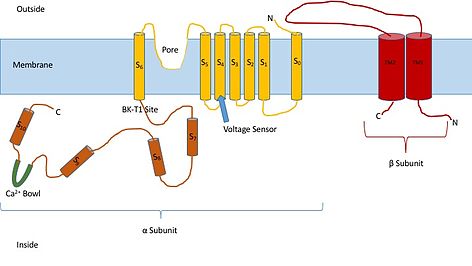

Knowing the structure of these channels can provide insight into their function and mechanism of gating. They are made up of two different subunits, alpha and beta. The alpha subunit is a tetramer which forms the pore, the voltage sensor, and the calcium sensing region. This subunit of the channel is made up of seven trans-membrane units, and a large intracellular region. The voltage sensor is made by the S4 transmembrane region, which has several Arginine residues which act to ‘sense’ the changes in charge and move in a very similar way to other voltage gated potassium channels. As they move in response to the voltage changes they open and close the gate. The linker between the S5 and S6 region serves to form the pore of the channel. Inside of the cell, the main portion to note is the calcium bowl. This bowl is thought to be the site of calcium binding.[3]

The beta subunit of the channel is thought to be a regulatory subunit of the channel. There are four different kinds of the beta subunit, 1, 2, 3, and, 4. Beta 2 and 3 are inhibitory, while beta 1 and 4 are excitatory, or they cause the channel to be more open than not open. The excitatory beta subunits affect the alpha subunits in such a way that the channel seldom inactivates.[4]

Homology Classification and Descriptions

Human KCa Channels

Below is a list of the 8 known human calcium-activated potassium channel grouped according to sequence homology of transmembrane hydrophobic cores:[5]

Though not implied in the name, but implied by the structure these channels can also be activated by voltage. The different modes of activation in these channels are thought to be independent of one another. This feature of the channel allows them to participate in many different physiologic functions. The physiological effects of BK channels have been studied extensively using knockout mice. In doing so it was observed that there were changes in the blood vessels of the mice. The animals without the BK channels showed increased mean arterial pressure and vascular tone. These findings indicate that BK channels are involved in the relaxation of smooth muscle cells. In any muscle cell, increased intracellular calcium causes contraction. In smooth muscle cells the elevated levels of intracellular calcium cause the opening of BK channels which in turn allow potassium ions to flow out of the cell. This causes further hyperpolarization and closing of voltage gated calcium channels, relaxation can then occur. The knockout mice also experienced intention tremors, shorter stride length, and slower swim speed. All of these are symptoms of ataxia, indicating that BK channels are highly important in the cerebellum.[6]

Subtypes of BK Channels

Intermediate conductance channels seem to be the least studied of all of the channels. Structurally they are thought to be very similar to BK channels with the main differences being conductance, and the methods of modulation. It is known that IK channels are modulated by calmodulin, whereas BK channels are not.

IK channels have shown a strong connection to calcification in vasculature, as inhibition of the channel causes a decrease in vascular calcification. Over-expression of these channels has quite a different effect on the body. Studies have shown that this treatment causes proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. This finding has sparked further exploration surrounding these channels and researchers have found that IK channels regulate the cell cycle in cancer cells, B and T lymphocytes, and stem cells. These discoveries show promise for future treatments surrounding IK Channels.

Subtypes of IK Channels

Small conductance calcium activate potassium channels are quite different from their relatives with larger conductance. The main and most intriguing difference in SK Channels is that they are voltage insensitive. These channels can only be opened by increased levels of intracellular calcium. This trait of SK channels suggests that they have a slightly different structure than the BK and IK channels.

Like other potassium channels they are involved in hyperpolarization of cells after an action potential. The calcium activated property of these channels allows them to participate in vaso-regulation, auditory tuning of hair cells, and also the circadian rhythm. Researchers were trying to figure out which channels were responsible for the re-polarization and after-hyperpolarization of action potentials. They did this by voltage clamping cells, treating them with different BK, and SK channel blockers and then stimulating the cell to create a current. The researchers found that the re-polarization of cells happens because of BK channels and that a part of the after-hyperpolarization occurs because of current through SK channels. They also found that with blocking SK channels, current during after-hyperpolarization still occurred. It was concluded that there was a different unknown type of potassium channel allowing these currents.[7]

It is clear that SK channels are involved in AHP. It is not clear exactly how this happens. There are three different ideas on how this is done. 1) Simple diffusion of Calcium accounts for the slow kinetics of these currents, 2) The slow kinetics is due to other channels with slow activations, or 3) The Calcium simply activates a second messenger system to activate the SK channels. Simple diffusion has been shown to be an unlikely mechanism because the current is temperature sensitive, and a diffusive mechanism would not be temperature sensitive. This is also unlikely because only the amplitude of the current is changed with concentration of Calcium, not the kinetics of the channel activation.

Subtypes of SK Channels

Other subfamilies

Prokaryotic KCa Channels

A number of prokaryotic KCa channels have been described, both structurally and functionally. All are either gated by calcium or other ligands and are homologous to the human KCa channels, in particular the KCa1.1 gating ring. These structures have served as templates for ligand gating.

| Protein | Species | Ligand | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kch | Escherichia coli | Unknown | Channel | [8][9] |

| MthK | Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus | Calcium, Cadmium, Barium, pH | Channel | [10][11][12][13][14] |

| TrkA/TrkH | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | ATP, ADP | Channel | [15][16] |

| KtrAB | Bacillus subtilis | ATP, ADP | Transporter | [17] |

| GsuK | Geobacter sulfurreducens | Calcium, ADP, NAD | Channel | [18] |

| TM1088 | Thermotoga maritima | Unknown | Unknown | [19] |

See also

References

- ^ Vergara, C.; Latorre, R.; Marrion, N. V.; Adelman, J. P. (1998). "Calcium-activated potassium channels". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 8 (3): 321–329. doi:10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80056-1. ISSN 0959-4388. PMID 9687354. S2CID 40840564.

- ^ WEAVER, AMY K.; BOMBEN, VALERIE C.; SONTHEIMER, HARALD (2006-08-15). "Expression and Function of Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels in Human Glioma Cells". Glia. 54 (3): 223–233. doi:10.1002/glia.20364. ISSN 0894-1491. PMC 2562223. PMID 16817201.

- ^ Ghatta, Srinivas; Nimmagadda, Deepthi; Xu, Xiaoping; O'Rourke, Stephen T. (2006-04-01). "Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: Structural and functional implications". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 110 (1): 103–116. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.007. PMID 16356551.

- ^ "Calcium- and sodium-activated potassium channels | Introduction | BPS/IUPHAR Guide to PHARMACOLOGY". www.guidetopharmacology.org. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ Wei AD, Gutman GA, Aldrich R, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Wulff H (Dec 2005). "International Union of Pharmacology. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels". Pharmacological Reviews. 57 (4): 463–72. doi:10.1124/pr.57.4.9. PMID 16382103. S2CID 8290401.

- ^ Brenner, R (2000). "Cloning and functional characterization of novel large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel beta subunits, hKCNMB3 and hKCNMB4". J Biol Chem. 275 (9): 6453–6461. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.9.6453. PMID 10692449.

- ^ Sah, Pankaj (1996). "Ca2+ activated K+ Currents in Neurones: Types, physiological roles and modulation". Trends in Neurosciences. 19 (4): 150–154. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80026-9. PMID 8658599. S2CID 9504595.

- ^ Milkman R (Apr 1994). "An Escherichia coli homologue of eukaryotic potassium channel proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (9): 3510–4. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.3510M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.9.3510. PMC 43609. PMID 8170937.

- ^ Jiang Y, Pico A, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R (Mar 2001). "Structure of the RCK domain from the E. coli K+ channel and demonstration of its presence in the human BK channel". Neuron. 29 (3): 593–601. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00236-7. PMID 11301020.

- ^ Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R (May 2002). "Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel". Nature. 417 (6888): 515–22. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..515J. doi:10.1038/417515a. PMID 12037559. S2CID 205029269.

- ^ Smith FJ, Pau VP, Cingolani G, Rothberg BS (2013). "Structural basis of allosteric interactions among Ca2+-binding sites in a K+ channel RCK domain". Nature Communications. 4: 2621. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2621S. doi:10.1038/ncomms3621. PMID 24126388.

- ^ Ye S, Li Y, Chen L, Jiang Y (Sep 2006). "Crystal structures of a ligand-free MthK gating ring: insights into the ligand gating mechanism of K+ channels". Cell. 126 (6): 1161–73. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.029. PMID 16990139.

- ^ Dvir H, Valera E, Choe S (Aug 2010). "Structure of the MthK RCK in complex with cadmium". Journal of Structural Biology. 171 (2): 231–7. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.03.020. PMC 2956275. PMID 20371380.

- ^ Smith FJ, Pau VP, Cingolani G, Rothberg BS (Dec 2012). "Crystal structure of a Ba(2+)-bound gating ring reveals elementary steps in RCK domain activation". Structure. 20 (12): 2038–47. doi:10.1016/j.str.2012.09.014. PMC 3518701. PMID 23085076.

- ^ Cao Y, Jin X, Huang H, Derebe MG, Levin EJ, Kabaleeswaran V, Pan Y, Punta M, Love J, Weng J, Quick M, Ye S, Kloss B, Bruni R, Martinez-Hackert E, Hendrickson WA, Rost B, Javitch JA, Rajashankar KR, Jiang Y, Zhou M (Mar 2011). "Crystal structure of a potassium ion transporter, TrkH". Nature. 471 (7338): 336–40. Bibcode:2011Natur.471..336C. doi:10.1038/nature09731. PMC 3077569. PMID 21317882.

- ^ Cao Y, Pan Y, Huang H, Jin X, Levin EJ, Kloss B, Zhou M (Apr 2013). "Gating of the TrkH ion channel by its associated RCK protein TrkA". Nature. 496 (7445): 317–22. Bibcode:2013Natur.496..317C. doi:10.1038/nature12056. PMC 3726529. PMID 23598339.

- ^ Vieira-Pires RS, Szollosi A, Morais-Cabral JH (Apr 2013). "The structure of the KtrAB potassium transporter". Nature. 496 (7445): 323–8. Bibcode:2013Natur.496..323V. doi:10.1038/nature12055. hdl:10216/110345. PMID 23598340. S2CID 205233489.

- ^ Kong C, Zeng W, Ye S, Chen L, Sauer DB, Lam Y, Derebe MG, Jiang Y (2012). "Distinct gating mechanisms revealed by the structures of a multi-ligand gated K(+) channel". eLife. 1: e00184. doi:10.7554/eLife.00184. PMC 3510474. PMID 23240087.

- ^ Deller MC, Johnson HA, Miller MD, Spraggon G, Elsliger MA, Wilson IA, Lesley SA (2015). "Crystal Structure of a Two-Subunit TrkA Octameric Gating Ring Assembly". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0122512. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1022512D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122512. PMC 4380455. PMID 25826626.

External links

- Calcium-Activated+Potassium+Channels at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels". IUPHAR Database of Receptors and Ion Channels. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology.