Search results

Appearance

There is a page named "Blood Feast" on Wikipedia

- Blood Feast is a 1963 American splatter film. It was composed, shot, and directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis, written by Allison Louise Downe from an idea...22 KB (2,609 words) - 00:00, 14 January 2025

- Blood Feast are an American extreme metal band that formed in 1985 in Bayonne, New Jersey, United States, under the name of Bloodlust. The band broke...7 KB (770 words) - 04:51, 16 December 2024

- The Feast of the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ was in the General Roman Calendar from 1849 to 1969. It was focused on the Blood of Christ...6 KB (961 words) - 04:36, 14 February 2024

- Blood Feast (Spanish: La noche de los mil gatos, lit. Night of a Thousand Cats) is a 1972 Mexican exploitation horror film written and directed by René...6 KB (576 words) - 00:29, 11 October 2024

- Feast of Corpus Christi (Ecclesiastical Latin: Dies Sanctissimi Corporis et Sanguinis Domini Iesu Christi, lit. 'Day of the Most Holy Body and Blood of...48 KB (5,127 words) - 05:06, 18 February 2025

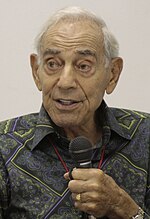

- In 1963, he directed Blood Feast, widely considered the first splatter film. In the 15 years following its release, Blood Feast took in an estimated $7...32 KB (3,338 words) - 10:41, 9 February 2025

- Delahoussaye. It is the sequel to the 1963 film Blood Feast. Filmed under a working title of Blood Feast 2: Buffet of Blood and using the same grindhouse style as...5 KB (476 words) - 22:53, 19 January 2025

- showing of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Waters played a minister in Blood Feast 2: All U Can Eat, directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis. In the 1980s, Waters...81 KB (6,851 words) - 09:30, 14 March 2025

- goddess Sheetar. The film was originally conceived to be a sequel to Blood Feast, but it was then changed to be a standalone film of its own. Although...6 KB (620 words) - 22:53, 19 January 2025

- Lewis and Friedman entered into uncharted territory with 1963's seminal Blood Feast, considered by most critics to be the first "gore" film. Because of the...18 KB (1,921 words) - 10:07, 18 January 2025

- p.m. on the last Saturday of the feast, immediately after a celebratory Mass at the Church of the Most Precious Blood. This is a Roman Catholic candlelit...17 KB (1,993 words) - 01:14, 22 December 2024

- she said. In 2015, Monk was added to the cast for the remake movie of Blood Feast. In April 2010, Nine Network announced Monk would be a special guest...35 KB (2,642 words) - 10:49, 17 March 2025

- types of films she has starred in (which include Party Bus to Hell, Blood Feast, House of Bad, Dread Central, and Shock Till You Drop), she is considered...8 KB (353 words) - 18:11, 15 June 2024

- he went on to star in some of the director’s best known works such as Blood Feast. In addition to playing principal roles, Kerwin served variously as the...10 KB (640 words) - 09:22, 2 August 2024

- Mason then acted in the gore movies pioneered by Herschell Gordon Lewis, Blood Feast and Two Thousand Maniacs! Her centerfold was photographed by Pompeo Posar...5 KB (549 words) - 20:21, 9 March 2025

- 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013. Russell, Xavier (October 2, 1986). "Blood Feast". Kerrang!. Vol. 130. London, UK: United Magazines Ltd. p. 18. Schäfer...61 KB (5,585 words) - 20:58, 11 March 2025

- Welterweight Champion, worked as a garbage man for 6 months. The films Blood Feast, Scanners III: The Takeover and Child's Play 3 all feature minor characters...15 KB (1,476 words) - 15:22, 20 February 2025

- Friedman, whose most famous films include Blood Feast (1963), Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964), Color Me Blood Red (1965), The Gruesome Twosome (1967) and...88 KB (10,252 words) - 00:03, 20 March 2025

- Feast is a 2005 American action horror comedy film directed by John Gulager, produced by Michael Leahy, Joel Soisson, Larry Tanz and Andrew Jameson. It...9 KB (1,042 words) - 10:16, 17 March 2025

- and uses their blood as paint. It is the third part of what the director's fans have dubbed "The Blood Trilogy," including Blood Feast (1963) and Two...8 KB (966 words) - 06:02, 19 January 2025

- Encyclopedia (1913) Feast of the Most Precious Blood by Ulrich F. Mueller 104280Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) — Feast of the Most Precious BloodUlrich F. Mueller

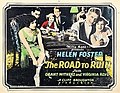

- Blood Feast is a 1963 American horror film about an Egyptian caterer who kills various women in suburban Miami to use their body parts to bring to life

- which you may not wish to read at your current level. At the Welcoming Feast, Harry sees the Bloody Baron at the Slytherin table. He is apparently sitting