Auto-brewery syndrome

| Auto-brewery syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gut fermentation syndrome, Endogenous ethanol fermentation |

| |

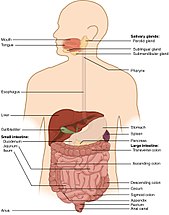

| Digestive system | |

Auto-brewery syndrome (ABS) (also known as gut fermentation syndrome, endogenous ethanol fermentation or drunkenness disease) is a condition characterized by the fermentation of ingested carbohydrates in the gastrointestinal tract of the body caused by bacteria or fungi.[1] ABS is a rare medical condition in which intoxicating quantities of ethanol are produced through endogenous fermentation within the digestive system.[2] The organisms responsible for ABS include various yeasts and bacteria, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. boulardii, Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococcus faecium.[1] These organisms use lactic acid fermentation or mixed acid fermentation pathways to produce an ethanol end product.[3] The ethanol generated from these pathways is absorbed in the small intestine, causing an increase in blood alcohol concentrations that produce the effects of intoxication without the consumption of alcohol.[4]

Researchers speculate the underlying causes of ABS are related to prolonged antibiotic use,[5] poor nutrition and/or diets high in carbohydrates,[6] and to pre-existing conditions such as diabetes and genetic variations that result in improper liver enzyme activity.[7] In the last case, decreased activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase can result in accumulation of ethanol in the gut, leading to fermentation.[7] Any of these conditions, alone or in combination, could cause ABS, and result in dysbiosis of the microbiome.[5]

Another variant, urinary auto-brewery syndrome, is when the fermentation occurs in the urinary bladder rather than the gut.

Claims of endogenous fermentation have been attempted as a defense against drunk driving charges, some of which have been successful, but the condition is so rare and under-researched they are currently not substantiated by available studies.[7]

Symptoms and signs

This disease can have profound effects on everyday life. Symptoms that usually accompany ABS include elevated blood alcohol levels as well as symptoms consistent with alcohol intoxication—such as slurred speech, stumbling, loss of motor functions, dizziness, and belching.[8] Mood changes and other neurological problems have also been reported.[1] Several cases in the United States and one in Belgium have argued endogenous fermentation as a defense against drunk driving.[7][9]

Risk factors

Certain clinical conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and liver cirrhosis have been identified as producing higher levels of endogenous ethanol.[4] Research has also shown that Klebsiella bacteria can similarly ferment carbohydrates to alcohol in the gut, which can accelerate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.[10] Gut fermentation can occur in patients with short bowel syndrome after surgical resection because of fermentation of malabsorbed carbohydrates.[1]

Kaji et al. noticed a correlation between this syndrome and previous abdominal surgeries and disturbances, such as a dilation of the duodenum. Stagnation of the contents ensues, which favors proliferation of the causative organisms.[8]

Gut fermentation syndrome has been investigated, but eliminated, as a possible cause of sudden infant death syndrome.[11]

Metabolic action

Fermentation is a biochemical process during which yeast and certain bacteria convert sugars to ethanol, carbon dioxide, as well as other metabolic byproducts.[12][13] The fermentation pathway involves pyruvate formed from yeast in the EMP pathway, while some bacteria obtain pyruvate through the ED pathway.[12] Pyruvate is then decarboxylated to acetaldehyde in a reaction involving the enzyme pyruvate decarboxylase.[12] Reduction of acetaldehyde to ethanol produces NAD+, which is catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH).[12] ADH rids the body of alcohol through a process called first pass metabolism.[7] However, if the rate of ethanol breakdown is less than the rate of production, intoxication ensues.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Alcohol levels within the body are usually detected through blood or breath. The best way to identify endogenous ethanol in the bloodstream is through gas chromatography. In gas chromatography the breath or blood is heated so that the different components of the vapor or blood separate. The volatile compounds then pass through a chromatograph that isolates ethanol from the other volatiles so that it can be quantified.[14]

More convenient methods include serum measurements and breathalyzers, especially during an acute attack at home.[10] Different countries have different baselines for blood alcohol levels when identifying intoxication through breathalyzers. In the United States it is 0.08 g/dL.[citation needed]

In diagnosing ABS through serum measurement methods, patients must fast in order that baseline blood alcohol and blood glucose levels can be established. They are then administered a dose of IG glucose to see if there is an increase in blood alcohol as well as blood sugar.[15] Blood glucose level can be measured with enzyme-amperometric biosensors, as well as with urine test strips.[16] Many of these tests are performed in combination to rule out lab mistakes and alcohol ingestion so that the syndrome is not misdiagnosed.[10]

Treatment

First, patients diagnosed with ABS are treated for the immediate symptoms of alcohol intoxication.[1] Next, patients can take medications if they test positive for the types of fungi or bacteria that cause gut fermentation. For example, antifungals such as fluconazole or micafungin can be prescribed by a physician.[8][6][17] Often, probiotics are given concurrently to ensure that the proper bacteria recolonize the gut, and to prevent recolonization by the microorganisms that caused the syndrome.[17] Patients also typically undergo a diet therapy where they are placed on a high protein, low carbohydrate diet to avoid the symptoms of ABS.[1] The treatments listed above can be used individually or in combination to reduce the effects of the syndrome.[1]

Case studies

- In 2019, a 25-year-old man presented with symptoms consistent with alcohol intoxication, including dizziness, slurred speech and nausea. He had no prior alcoholic drinks but had a blood alcohol level of 0.3 g/dL. The patient was given 100 mg of the antifungal fluconazole daily for 3 weeks, and his symptoms were resolved.[8]

- In 2004, a 44-year-old male was treated with the antibiotics clavulanic acid and amoxicillin for an unrelated condition. Eight days after being discharged, he returned to the emergency room with abdominal pain and belching and was in a state of confusion. An esophagogastroscopy showed the presence of S. cerevisiae and C. albicans in his gastric fluid, causing endogenous ethanol production.[18]

- Reported in 2001, a 13-year-old girl with short gut syndrome suddenly developed symptoms of intoxication after eating "excess carbohydrates and juices". She had no access to alcohol any time the symptoms were present. Her small intestine was colonized by two organisms: C. glabrata and S. cerevisiae. She was treated with fluconazole and her symptoms resolved.[19]

- A case of urinary fermentation of carbohydrates by endogenous microorganisms leading to urinary ethanol has been reported. This single reported case is associated with diabetes due to the presence of sugar in the urine for the yeast to ferment. The person did not develop symptoms of intoxication, but did test positive in the urine for alcohol. Fermentation may continue after the urine is expressed, resulting in it developing an odor resembling wine.[20][21]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Painter K, Cordell BJ, Sticco KL (2020). "Auto-brewery Syndrome (Gut Fermentation)". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30020718. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ Kaji H, Asanuma Y, Yahara O, Shibue H, Hisamura M, Saito N, et al. (1984). "Intragastrointestinal alcohol fermentation syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature". Journal of the Forensic Science Society. 24 (5): 461–71. doi:10.1016/S0015-7368(84)72325-5. PMID 6520589.

- ^ Fayemiwo SA, Adegboro B (2013-11-20). "Gut fermentation syndrome". African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology. 15 (1): 48–50. doi:10.4314/ajcem.v15i1.8. ISSN 1595-689X.

- ^ a b Hafez EM, Hamad MA, Fouad M, Abdel-Lateff A (May 2017). "Auto-brewery syndrome: Ethanol pseudo-toxicity in diabetic and hepatic patients". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 36 (5): 445–450. Bibcode:2017HETox..36..445H. doi:10.1177/0960327116661400. PMID 27492480. S2CID 3666503.

- ^ a b Cordell BJ, Kanodia A, Miller GK (January 2019). "Case-Control Research Study of Auto-Brewery Syndrome". Global Advances in Health and Medicine. 8: 2164956119837566. doi:10.1177/2164956119837566. PMC 6475837. PMID 31037230.

- ^ a b Saverimuttu J, Malik F, Arulthasan M, Wickremesinghe P (October 2019). "A Case of Auto-brewery Syndrome Treated with Micafungin". Cureus. 11 (10): e5904. doi:10.7759/cureus.5904. PMC 6853272. PMID 31777691.

- ^ a b c d e Logan BK, Jones AW (July 2000). "Endogenous ethanol 'auto-brewery syndrome' as a drunk-driving defence challenge". Medicine, Science, and the Law. 40 (3): 206–15. doi:10.1177/002580240004000304. PMID 10976182. S2CID 6926029.

- ^ a b c d Akhavan BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Thomas EJ (September 2019). "Drunk Without Drinking: A Case of Auto-Brewery Syndrome". ACG Case Reports Journal. 6 (9): e00208. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000208. PMC 6831150. PMID 31750376.

- ^ "2 promille alcohol in zijn bloed, maar toch vrijgesproken voor rijden onder invloed: man uit Brugge lijdt aan autobrouwerijsyndroom". VRT (in Dutch). 22 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Yuan J, Chen C, Cui J, Lu J, Yan C, Wei X, et al. (October 2019). "Fatty Liver Disease Caused by High-Alcohol-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae". Cell Metabolism. 30 (4): 675–688.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018. PMID 31543403.

- ^ Geertinger P, Bodenhoff J, Helweg-Larsen K, Lund A (September 1982). "Endogenous alcohol production by intestinal fermentation in sudden infant death". Zeitschrift für Rechtsmedizin. Journal of Legal Medicine. 89 (3): 167–72. doi:10.1007/BF01873798. PMID 6760604. S2CID 29917601.

- ^ a b c d Fath BD, Jørgensen SE (23 August 2018). Encyclopedia of ecology. Fath, Brian D. (Second ed.). Amsterdam, Netherlands. ISBN 978-0-444-64130-4. OCLC 1054599976.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mendez ML (2016). Electronic noses and tongues in food science. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-800402-9. OCLC 940961460.

- ^ Jones AW, Mårdh G, Anggård E (1983). "Determination of endogenous ethanol in blood and breath by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 18 (Suppl 1): 267–72. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(83)90184-3. PMID 6634839. S2CID 36120089.

- ^ Eaton KK (November 1991). "Gut fermentation: a reappraisal of an old clinical condition with diagnostic tests and management: discussion paper". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 84 (11): 669–71. doi:10.1080/13590840410001734929. PMC 1295472. PMID 1744875.

- ^ Simic M, Ajdukovic N, Veselinovic I, Mitrovic M, Djurendic-Brenesel M (March 2012). "Endogenous ethanol production in patients with diabetes mellitus as a medicolegal problem". Forensic Science International. 216 (1–3): 97–100. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.09.003. PMID 21945304.

- ^ a b Malik F, Wickremesinghe P, Saverimuttu J (August 2019). "Case report and literature review of auto-brewery syndrome: probably an underdiagnosed medical condition". BMJ Open Gastroenterology. 6 (1): e000325. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000325. PMC 6688673. PMID 31423320.

- ^ Spinucci G, Guidetti M, Lanzoni E, Pironi L (July 2006). "Endogenous ethanol production in a patient with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 18 (7): 799–802. doi:10.1097/01.meg.0000223906.55245.61. PMID 16772842.

- ^ Dashan A, Donovan K (August 2001). "Auto-brewery syndrome in a child with short gut syndrome: case report and review of the literature". J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 33 (2): 214–215. doi:10.1097/00005176-200108000-00024. PMID 11568528.

- ^ "Auto-Brewery Syndrome: Woman Failed Urine Tests As Her Bladder Was Brewing Alcohol". International Business Times. 26 February 2020.

- ^ Kruckenberg KM, DiMartini AF, Rymer JA, Pasculle AW, Tamama K (February 2020). "Urinary Auto-brewery Syndrome: A Case Report". Annals of Internal Medicine. 172 (10): 702–704. doi:10.7326/L19-0661. PMID 32092761. S2CID 211475605.