Architecture of Qatar

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Qatar |

|---|

|

| History |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

The architecture of Qatar, similarly to other Persian Gulf nations, is strongly influenced by Islamic architecture. Qatari architecture has retained its Islamic essence, evident in the unadorned, humble designs of its mosques. This tradition extends to other buildings, which feature many decorative elements such as arches, niches, intricately carved plaster patterns, gypsum screens (kamariat and shamsiat), and battlements atop walls and towers.[1]

The country's hot desert climate heavily influenced the selection of building materials in traditional architecture. Rough stones, sourced from rocky hillsides or coastal areas, were commonly used. These stones were systematically arranged in rows, with clay from the Persian Gulf serving as the binding agent. This clay was also employed to coat wall surfaces, both inside and outside, and to fill the gaps between stones. Ceilings were similarly covered with clay. In situations where stones were scarce, mud bricks were sometimes substituted. As construction techniques evolved, clay, which was unsuitable for the rainy winter season, was gradually replaced with gypsum mortar for plastering walls. Various types of wood were incorporated as well, particularly wooden beams for supporting ceilings. Limestone, quarried from nearby rocky hills, was also occasionally used.[2]

Types of traditional architecture

Qatar's architectural heritage, like that of other Arabian Peninsula countries, includes buildings from the 17th to early 20th centuries, with at least one surviving structure dating hundreds of years earlier: Murwab Fort. Qatari architecture is categorized into three main types: religious, civil, and military.[3]

Religious architecture includes mosques, which serve as places for the five daily prayers and the Friday congregational prayer. Mosques in Qatar are characterized by their simplicity and modesty yet will occasionally contain attractive ornamentation.[3]

Included among civil architecture are palaces, houses and marketplaces. Palaces were grand structures that housed local rulers and displayed a high level of opulence. Homes for both the nobility and common people were constructed from clay and stones. Noble homes were typically large, while commoners' houses were smaller. Initially, markets (also known as souqs) consisted of rows of wooden pillars covered with fabric or burlap. Over time, they evolved to include structures made of stone and clay, forming two rows of shops facing each other.[3]

Military architecture consists of fortresses and defensive walls. Fortresses were often built along the borders, and featured watchtowers at the corners and various rooms along the interior walls, resembling castles. Large defensive walls made of stone and clay often enclosed settlements, with main gates that were closed at nightfall. Towers were erected at intervals along these walls for added defense.[3]

Climatic and regional adaptations

The architecture in Qatar has been significantly shaped by climate and environmental factors, which have influenced the design and variety of buildings, including houses, mosques, forts, and marketplaces.[4]

Due to the region's desert climate, which features minimal rainfall in winter and high temperatures and humidity in summer, flat roofs are predominant instead of pitched ones. To mitigate the heat, architects designed shaded areas adjacent to mosques and houses, which open directly onto courtyards. The intense sunlight led to the use of relatively small lighting openings compared to the expansive exterior walls.[4]

Residential buildings in Qatar and the Gulf region often feature rectangular windows (darisha) that open onto the courtyard. In living rooms (majlis) and upper-floor rooms, windows typically face both the courtyard and the road. Additionally, for ventilation and lighting, other openings known as badjeer are commonly constructed in upper rooms but are rarely found in lower ones.[4]

Coastal Qatari architecture shows influences from Iranian architecture, while inland architecture is more reflective of Najdi styles, particularly in fortified houses found in Al Rayyan, Al Wajbah, and Umm Salal Mohammed. Coastal villages like Al Jumail and Al Wakrah demonstrate the adaptation of inexpensive Persian Gulf models, with houses constructed from local materials like hasa (rubble) and juss (limestone mortar). The architecture of these areas was designed to benefit from on-shore breezes and to meet the economic needs of the inhabitants which comprised fishing and pearling. For instance, Al Wakrah contains more historic wind towers than any other settlement in the country.[5]

Houses

Layout and design

Qatari houses, the smallest urban units, are centered around courtyards, which serve as venues for family functions. These courtyards provide ventilation, sunlight, and a private space for domestic activities and social interactions. The number of courtyards varies based on family size and wealth. Surrounding the courtyard are multifunctional rooms used for sleeping, eating, and socializing, with their usage depending on the season and climatic conditions.[5]

Privacy and territoriality are key considerations in Qatari house design. Spaces are segregated to separate male visitors from the family and young men from women. The majlis always has a separate access route to maintain privacy. As families grow, new plots and access points are established. Houses typically feature flat roofs to provide shade, with small window openings to reduce heat. Badjeer ventilation openings are common in majlis and upper rooms, enhancing airflow and comfort. The design of Qatari houses includes shaded areas like terraces and verandas to provide comfortable spaces for outdoor activities.[5]

Privacy

In Qatari architecture, houses are viewed as a private entity, meant to be discreet and unassuming from street view. Typically, only one external wall faces the street, and it is designed to maintain privacy, often featuring minimal openings. Any windows or doors are screened to prevent outsiders from seeing into the household's private areas. Privacy is a fundamental principle in Islamic societies, reflected in the separation of male and female spaces within the home. Regardless of a house's size, maintaining privacy remains a crucial aspect of its design.[5]

Guests

Qatari residential developments often feature extensive internal and external spaces. The men's section of the house usually includes accommodations for guests, with some homes providing a guest room and bathroom facilities. In other cases, guests might sleep overnight in the majlis, a traditional sitting area. This design reflects the importance of hospitality and the majlis in Qatari homes.[5]

Majlis

In traditional affluent Qatari households, the majlis served as one of the most significant spaces.[6] This formal, gender-specific reception area was utilized for hosting visitors, conducting business, and leisure activities. The majlis also functioned as a forum for social interaction, discussion, and conflict resolution, with a particular emphasis on the wisdom and authority of elder members.[7] These gatherings occasionally served as platforms for various forms of folk arts. In the past, the "dour", or spacious rooms designated for these gatherings, hosted seafarers, dhow captains (noukhadha), and enthusiasts of folk arts between pearl fishing seasons. Here, they engaged in al-samra, evenings of song and dance, celebrated during weddings and other occasions for entertainment.[8] The majlis represented the homeowner's temperament and status, and it continues to hold an essential communicative role within Qatari society, facilitating interactions with outsiders.[6]

Typically, the majlis was a designated room near the courtyard entrance, allowing guests access without intruding into the private parts of the house. It was often the only room with windows facing the street and was the most elaborately decorated area in the house. Ceilings made from mangrove and palm were often painted with colorful geometric patterns. Wealthier homes featured colored glass windows and sometimes included window screens or carved gypsum panels with symmetrical geometric designs. Simpler houses used more modest decorations, such as recessed niches (roshaneh). Floors of hard-packed earth or gypsum were covered with the household's finest rugs and cushions (masanid) and other sentimental items.[6]

Another type of majlis, known as the dikka (pronounced dacha or dicha in Qatari Arabic), was an elevated earthen platform typically found outside. Sometimes situated in a public area, the dikka was covered with mats and shaded by barasti walls or a tent. It could also take the form of a bench along the outside of a structure. Although this type of majlis was not common in Doha, it remains visible in the previously inhabited settlements surrounding the city. It was also historically present in the Old Amiri Palace, which is now the centerpiece of the National Museum of Qatar.[6]

Decoration

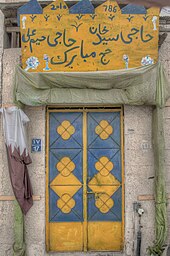

The houses of wealthy Qataris and Gulf residents are characterized by intricate gypsum decorations, often geometric or plant-based. Wooden doors and windows are similarly adorned, sometimes featuring colorful glass. Exterior walls might be decorated with recesses and arches, while interior walls are plastered with inscribed gypsum panels and friezes. Rawashin, or recessed niches, are commonly used for storing lamps and other items, adding both functional and decorative elements to the rooms.[5]

Water usage

In traditional Qatari houses, water was a vital resource carefully managed. Most homes, especially those belonging to wealthier families, featured a water well within the courtyard. This well was the primary source of water for various domestic activities, including washing clothes, cleaning kitchenware, showering, and watering any plants within the courtyard. Washing and cooking were often done in the courtyard, taking advantage of the open space and natural light.[5]

Traditional Qatari houses featured simple but functional bathrooms. These washrooms, often adjoined to each of the typically one to two main rooms of a house, were designed to ensure privacy while facilitating easy access to water from the well. All family members used the washrooms at all the times of the day for various purposes, including bathing, washing hands and feet, and other personal hygiene activities.[5]

Access

The architectural approach to accessing homes in Islamic societies varies widely, influenced by factors such as land availability, safety, and noise insulation. In Qatar, houses often open onto either a cul-de-sac or a public thoroughfare. These entrances usually incorporate a hairpin curve or right-angled turn to ensure privacy. The positioning of street doorways is carefully considered to avoid direct alignment with opposite entrances, enhancing privacy and preventing potential nuisances. Unlike other Islamic countries, where separate family entrances are common, most Qatari houses feature a single entrance with two doors: a large door for family access and a smaller one for guests.[5]

Madabis

The manufacturing of date syrup is one of the oldest industries in Qatar, dating back to at least the 17th century. Qatar's natural landscape can support only a few types of agriculture, and date palms are among them. The syrup was obtained by using a traditional date press called madabis or madbasa. Due to its high-calorie content and nutrient density, it was a cheap and quick source of energy for the locals, particularly pearl divers.[9]

The construction of madabis employed traditional techniques reflective of the era. Utilizing locally available materials such as stones, limestone, sandstone, and coral, craftsmen built these rectangular or square rooms with meticulous attention to detail. The outer walls, made of irregular stones, provided structural integrity, while inner walls crafted from beachrocks (froush) added insulation. Traditional roofing methods, including danshil beams and palm fronds, ensured stability and protection from the elements.[10]

Mosques

Qatari mosques, much like their counterparts in the broader Persian Gulf region, exhibit a distinct architectural style characterized by a rectangular or square courtyard. This courtyard typically features a qibla gallery on one side, oriented towards Mecca, and covered with thin wooden logs known as danshil or the more robust khashab-al-murabaa. The gallery's walls include a mihrab niche at its center, with a pulpit niche (known as minbar) to the right.[11]

The courtyard's floor is often covered with sea sand, locally abundant. Access to the courtyard is provided through three doors: one directly opposite the qibla gallery and two on the sides. Ablution areas (maybaa) and minarets are strategically placed, usually at the northeast corner of the courtyard.[11]

The structural design of mosques in Qatar, dating from the late 18th to early 20th centuries, typically includes a wooden pulpit and minimal ornamental details. The mihrab niche, projecting from the qibla wall, may be covered with one or two domes. The ceiling structures incorporate lightweight bamboo or reed lattice patterns, providing a decorative yet functional element.[11]

Domes are a rare but notable feature in some Qatari mosques, such as the Abu Al-Qubaib mosque in Doha and Dukhan Masjid in Dukhan, where they rest on square bases made of white stone and plaster. The gallery pillars are generally square in cross-section, although historical records indicate the existence of cylindrical columns in older mosques like those in Zubarah.[11]

Windows in the qibla gallery are designed to allow ventilation and light, with wooden frames and iron bars providing security. The place of ablution, often a rectangular platform in the courtyard, includes a well for ritual washing.[11]

Minarets in Qatari mosques vary in shape, ranging from conical to cylindrical, and often include balconies for the muezzin to call to prayer. These structures are typically adorned with plastered stone or wood railings and may feature decorative elements like small columns (hilya) on their domes.[11]

Forts

Qatar's forts represent an essential part of the country's architectural heritage, reflecting the strategic and defensive needs of different historical periods. Key sites include:

Murwab Fort

Located on the edge of a fertile lowland, approximately 15 km north of Dukhan, the excavated site of Murwab Fort can be found. This site included about 250 houses surrounding the fortress. Excavations revealed two mosques, numerous graves, and a well within the fortress courtyard.[12] Murwab Fort is the oldest known fort in the country and was built over the ruins of a previous fort which was destroyed by a fire.[13] It is rectangular in shape and is thought to have served as a palatial residence. The structure is similar to other palatial residences dating to the Abbasid period elsewhere in the Middle East.[14] A large courtyard with doors leading to twelve different rectangular rooms is in the center of the fort. The entrance, located on the north side, is 4.6 feet wide. Construction materials used for the wall were rocks and mud.[15]

Ar Rakiyat Fort

Situated 110 km from Doha, near Zubarah, Ar Rakiyat Fort is a typical desert fortress with a rectangular plan, four corner towers, and rooms along its northern, eastern, and western walls. Built from limestone and clay, it includes a freshwater well and was restored in 1988. The fortress dates back to between the 17th and 19th centuries, with archaeological evidence pointing to its use during the Abbasid period.[16] In 2022, using traditional building materials, the Department of Architectural Conservation of Qatar Museums completed the second restoration of the main structural building components including plastering, flooring, installation of a wooden ceiling, and doors.[17][18]

Ath Thaqab Fort

Located in Ath Thaqab in northwest Qatar, Ath Thaqab Fort has a rectangular shape with four corner towers and a main entrance in the northern wall. The site includes a deep well and rooms around the courtyard. Built from limestone and clay, the fort likely dates to the 17th-19th centuries. The discovery of an Abbasid coin suggests an earlier historical context, though further excavations are required for a definitive answer.[19]

Al Wajbah Fort

Al Wajbah Fort is located in the locality of Al Wajbah in Al Rayyan, 15 km west of Doha.[20] The fort was built in 1882 and was the location of an important battle when the army of Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani subdued the Ottoman army in 1893, in what would eventually be known as the Battle of Al Wajbah.[21] It was used as the residence of Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani at various periods. The fort's most prominent features are its four watchtowers.[22] Constructed from local stone and clay, it underwent restoration in the later 20th century.[23]

Zubarah Fort

Situated in the northwest of the Qatar Peninsula, the Al Zubara Fort was built in 1938 and later restored. It has a square plan with four corner towers, high walls, and a central courtyard. The fortress features a mosque, galleries, and rooms with traditional wooden ceilings. It was initially constructed for border protection and later used by border guard forces.[24] It occupies the UNESCO World Heritage site of Zubarah, and is considered the most notable attraction of the site.[25]

Al Koot Fort

One of Doha's few remaining military installations, Al Koot Fort was built around 1925 to serve as a prison. It has a square plan with high walls and corner towers. The fortress was restored in 1978 and opened as an exhibition space in 1985. The design includes features for effective prisoner control and surveillance.[26] The fort was built in close proximity to Souq Waqif so that market thieves could easily be apprehended by officers on duty.[27]

Construction materials

Limestone

The Qatari Peninsula's surface is predominantly limestone, covered with a thin layer of sand, loess, and clay, forming the region's agricultural soils. Limestone has been a fundamental building material for centuries, used in the construction of houses, castles, towers, and mosques. Builders in Qatar and the Persian Gulf utilized various locally available stones, including coral slabs and pebbles. Coral slabs, obtained from coastal areas at low tide, were especially valued for their use in wall masonry, niches, and wall lintels. Another type of limestone, collected from the surface or cut from limestone hills, was used in construction but required covering with gypsum plaster for durability.[28]

Coral slabs (frush)

Coral slabs are tiles measuring approximately 70 cm x 50 cm and 7 cm thick, sourced from coastal areas. They were prized for their suitability in building due to their availability and ease of use in construction, as corals are notably prevalent in Qatari waters which contain 48% of the coral reefs in the Persian Gulf.[29] These slabs were primarily used for walls, niches, and other architectural features.[28]

Clay

Natural clay was abundant on some coastal terraces and served as an excellent bonding material in masonry. It was used to coat the exterior walls of buildings and for making mud bricks. To improve the clay's binding properties, chopped straw was added. Despite its advantages, clay was susceptible to weather conditions, particularly rain, necessitating periodic maintenance and protective measures.[28]

Gypsum (calcium sulfate)

Gypsum, locally sourced from areas like Al Khor, Simaisma, and Fuwayrit, was a crucial material in Qatari construction. It was used for plastering walls inside and outside buildings, making molds for ornaments, and enhancing the weather resistance of structures. Gypsum plaster covered masonry walls to prevent moisture penetration and decorate the exterior surfaces.[28]

Palm trunks

Palm tree trunks, after being cut and dried, were used extensively for roofing in traditional Qatari houses. These trunks provided structural support but were less load-bearing than other materials like danshil. They were typically used in combination with other roofing materials to create a stable and durable roof.[28]

Danshil (stabilized wood)

Danshil, a type of stabilized wood, was commonly used in roofing, door lintels, and structural connectors in buildings. This material, imported from East Africa, was prized for its durability and resistance to weather conditions. It was often painted in bright colors and used decoratively in architectural elements.[28]

Mangroves

Mangrove stems, used in the form of mats, were placed above danshil to create a base layer in roofing. This material was valued for its strength and durability, often used interchangeably with palm branches (duun) and bamboo (baszhil).[28]

Baszhil (bamboo)

Bamboo, known locally as baszhil, was imported from India and East Africa and was used in making doors, chests, and cabinets. It was placed above danshil in roofing and sometimes painted in vibrant colors. Bamboo's long transportation distance did not significantly affect its cost, making it a popular material in the Persian Gulf.[28]

Duun (palm branches)

Palm branches were gathered and joined to form large mats, used to cover danshil and baszhil. These mats provided additional support and protection in roofing structures, contributing to the overall stability and weather resistance of traditional Qatari buildings.[28]

Teak wood

Teak wood, known for its strength and durability, was imported from India and East Africa. It was used in various construction elements, including doors and furniture. Despite the long transportation distance, teak wood remained an affordable and popular material in the region.[28]

Tamarisk wood

Wood from the tamarisk tree is prized for its use in the construction of door frames, door bolts and back-of-door support frames.[30]

Modern architecture

Qatar in the past two decades has pinpointed its place on the world map with prominent global landmarks including Education City which showcases architecture from numerous architects including Rem Koolhaas who designed the Qatar National Library during 2018 and the Qatar Foundation headquarters back in 2014.[31]

Among Qatar's notable architects is Japanese architect Arata Isozaki who contributed towards designing countless buildings in Education City,[32] including the Qatar National Convention Center (QNCC), the Liberal Arts and Science Building (LAS) and the Qatar Foundation Ceremonial Court.[31]

Qatar's art initiatives have expanded tremendously in recent years with the opening of massive great projects including the Doha Fire Station which exhibits art at the heart of the city.[33]

Arts and museums have played a pivotal role in improving Qatar's tourism and inviting people to understand Qatar's history and heritage with the openings of the National Museum of Qatar, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Msheireb Museums and the Museum of Islamic Arts.[33]

Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani has played a significant role in bringing art to Qatar,[34] particularly with the latest art installations at the Hamad International Airport (HIA) showcasing pieces of work by numerous global artists in collaboration with Qatar Museums Authority.[35]

Under the guidance of the CEO of Qatar Foundation, Sheikha Moza bint Nasser,[36] Education City has become a home for modernistic buildings originating from worldwide architects contributing to the building of schools, universities, offices, and accommodations for the community.[31][37]

Examples of modern architecture

In Education City:

- Qatar National Convention Center (2011) designed by Arata Isozaki[38]

- Qatar Foundation Ceremonial Court (2007) designed by Arata Isozaki[39]

- Qatar Foundation Headquarters (2014) designed by Rem Koolhaas[40]

- Northwestern University in Qatar (2017) designed by Antoine Predock[41]

- Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar (2008) designed by Ricardo Legorreta and Victor Legorreta[42]

- Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar (1998) designed by Mimar Consult[32]

- Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (2003) designed by Arata Isozaki[43]

- Liberal Arts and Science building (2004) designed by Arata Isozaki[44]

- Georgetown School of Foreign Service in Qatar (2010) designed by Ricardo Legorreta and Victor Legorreta[45]

- Texas A&M University in Qatar (2007) designed by Ricardo Legorreta and Victor Legorreta[46]

- Qatar Academy (1997) designed by Al Seed Consultant and Design Studio

- Awsaj Academy (2011) designed by James Cubitt and Partners

- Qatar Science and Technology Park (2009) designed by Woods Bagot[47]

- Strategic Studies Center (2014), also known as Think Bay designed by Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA)

- Qatar National Library (2018) designed by Rem Koolhaas[48]

- Sidra Medical and Research Center (2017) designed by Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects[49]

- Al Shaqab (2019) designed by Leigh & Orange Architects[50]

- Student Center (2012) designed by Ricardo Legorreta and Victor Legorreta

- Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies (2014) designed by Mangera Yvars Architects[51]

- Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art (2010) designed by Jean-Francois Bodin[52]

-

Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies designed by Mangera Yvars Architects

-

Northwestern University in Qatar designed by Antoine Predock

-

Qatar Foundation Headquarters designed by Rem Koolhaas

-

Qatar National Library designed by Rem Koolhaas

-

Three of the five matching skyscrapers associated with the Doha City Center Mall

References

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. p. 5.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jaidah, Ibrahim; Bourennane, Malika (2010). The History of Qatari Architecture 1800-1950. Skira. pp. 19–23. ISBN 978-8861307933.

- ^ a b c d Eddisford, Daniel; Carter, Robert (26 October 2016). "The Vernacular Architecture of Doha, Qatar" (PDF). University College London. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ Al-Muhannadi, Hamad (2012). "Chapter 9: The Traditional Roles of al-Majlis" (PDF). Studies in Qatari Folklore. Vol. 2. Heritage Department of the Ministry of Culture and Sports (Qatar). pp. 155–160. ISBN 978-9927122316. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 19–23.

- ^ "Traditional Qatari Culture" (PDF). Qatar Tourism. p. 11. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Al Maashani, Musllam; Menon, Lakshmi Venugopal (May 2023). "Traditional Date Presses (madabis) in Qatar" (PDF). Gulf Studies Centre of Qatar University. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 15–21.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. p. 29.

- ^ "History of Qatar" (PDF). Qatar Embassy in Thailand. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Qatar. London: Stacey International. 2000. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Settlements of Qatar". Qatar Museums. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Jaidah, Ibrahim; Bourennane, Malika (2010). The History of Qatari Architecture 1800-1950. Skira. p. 34. ISBN 978-8861307933.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 33–35.

- ^ "Qatar Museums restores historic Al Rakiyat Fort". thepeninsulaqatar.com. 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ^ "Qatar Museums restores Al Rakiyat Fort in the north-east of the country". ILoveQatar.net. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 35–37.

- ^ "Visit Qatar". Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Al Wajbah Fort is a landmark in the history of Qatar and a tourist attraction". The Consulate General of the State of Qatar. 18 November 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Museums and forts". Ministry of Interior (Qatar). Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 39–41.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. p. 42.

- ^ Sideridis, Dimitris (19 March 2019). "Al Zubarah: Vanished port is a gateway to Qatar's past". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 43–44.

- ^ "Al Koot Fort". Explore Qatar. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mohammad Jassim Al-Kholaifi (2006). Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage. pp. 105–108.

- ^ "Qatar home to 48% of coral reefs in Arabian Gulf". The Peninsula Qatar. 17 October 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Al-Obaidli, Saleh (2022). Ahşap Kapılar (Wooden Doors) (PDF) (in Turkish). Translated by Caymazoğlu, Yakup; Stiti, Mustapha. Doha: Al Waraq Printing Press. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Jodidio, Philip. (2014). Education city : building foundations for the future. Doha: Qatar Foundation, Capital Projects Directorate. ISBN 9788416142361. OCLC 899565075.

- ^ a b Bonilla, Leslie. "Pearls, Souqs and Daggers: Inside the Hidden Elements of Education City Architecture". The Daily Q. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ a b "Visit Qatar | Discover a Unique Destination". www.visitqatar.qa. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ "HE Sheikha Al Mayassa Al Thani, Chairperson of Qatar Museums, is the Guest Editor of the November 2022 Issue of Vogue Arabia". Vogue Arabia. 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Falconer, Morgan (2002-04-30). Butt, Hamad. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t097571.

- ^ "Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser | Qatar Foundation". www.qf.org.qa. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Explore Qatar's Education City". www.qf.org.qa. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Qatar National Convention Centre / Arata Isozaki". ArchDaily. 2013-09-10. Retrieved 2022-11-25.

- ^ "Ceremonial Court and the Ceremonial Green Spine". visitqatar.com. Retrieved 2022-11-25.

- ^ "QF Conversation: Rem Koolhaas". Qatar Foundation. 2017-11-08. Retrieved 2022-11-25.

- ^ "HBKU Carnegie Mellon / Legorreta + Legorreta". ArchDaily. 2014-12-12. Retrieved 2022-11-25.

- ^ "Home in Qatar - Carnegie Mellon University | CMU". www.cmu.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "The Building | Weill Cornell Medicine - Qatar". qatar-weill.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Liberal Arts and Science Building, Doha Qatar". www.archnet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "Georgetown University / LEGORRETA". ArchDaily. 2018-11-05. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "Texas A&M Engineering Building". www.qatar.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "Qatar / Woods Bagot". ArchDaily. 2013-07-31. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Our Building | Qatar National Library". www.qnl.qa. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Sidra Medical and Research Center / Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects". ArchDaily. 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Al Shaqab Equestrian Academy". Leigh & Orange Architects. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ^ "Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies by Mangera Yvars Architects | Universities". Architonic. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ "Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art". universes.art. Retrieved 2022-11-30.