Amduat

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

The Amduat[pronunciation?] (Ancient Egyptian: jmj dwꜣt, literally "That Which Is In the Afterworld", also translated as "Text of the Hidden Chamber Which is in the Underworld" and "Book of What is in the Underworld"; Arabic: كتاب الآخرة, romanized: Kitab al-Akhira)[1] is an important ancient Egyptian funerary text of the New Kingdom of Egypt. Similar to previous funerary texts, such as the Old Kingdom's Pyramid Texts, or the First Intermediate Period's Coffin Texts, the Amduat was found carved on the internal walls of a pharaoh's tomb.[2] Unlike other funerary texts, however, it was reserved almost exclusively for pharaohs until the Twenty-first Dynasty, or very select nobility.[2]

The Amduat tells the story of Ra, the Egyptian sun god who makes a daily journey through the underworld, from the time when the sun sets in the west till it rises again in the east. This is associated with imagery of continual death and rebirth, as the sun 'dies' when it sets, and through the trials of rebirth in the underworld, it is once again 'reborn' at the beginning of a new day. It is said that the deceased Pharaoh will take this same journey through the underworld, ultimately to be reborn and become one with Ra, residing with him forever.[3] Many gods, goddesses, and deities help both Ra and the deceased soul on this journey in a variety of ways, such as Khepri, Isis, and Osiris being some of the main ones.[2] This is alongside many unnamed or unknown deities, which are often given reference to within the text of the Amduat itself.

As well as enumerating and naming the inhabitants of the Duat (Egyptian word for the underworld), both good and bad, the illustrations of the work show clearly the topography of the underworld. Early fragments of the Amduat can be found in the tombs of Hatshepsut & Thutmose I (KV20), as well as Thutmose I (KV38), but the earliest complete version is found in KV34, the tomb of Thutmose III in the Valley of the Kings.[4]

Content of the Amduat

The underworld is divided into twelve hours of the night, each representing different allies and enemies for the Pharaoh/sun god to encounter. The Amduat names all of these gods and monsters, such as the serpent of Mehen or the 'World Encircler' which play a variety of roles to either help or harm Ra and the deceased soul. The main purpose of the Amduat is to give information about the geography of the underworld, as well as the names and descriptions of these gods and monsters to the Ba (or soul) of the dead Pharaoh, so he can call upon them for help or use their name to defeat them. [4]

The Amduat is represented in two forms within tombs: a shorter version of the text that simply covers the journey of Ra, and a much longer version that is both textually and pictorially represented. The long version typically contains the shorter version at the very end of the journey, as well as the directions for how the Amduat should be shown depicted on the walls of the tomb.[5]

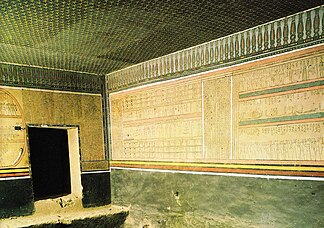

Visually, the Amduat is typically broken into 3 continuous horizontal registers, with vertical registers of text separating each of the 12 hours. Each of the vertical textual registers contain information about the title of the hour, name of the gateway (either a pylon, door, or gate that is guarded by a deity) that connects them, as well as the name of the region of the underworld in order to distinguish the progression of Ra's daily journey.[5] The 12 hours follow along through 12 distinct regions of the Duat, while the 3 registers represent some of the physical locations within these regions.[6] Additionally, at the end of each hour is a textual explanation of what happened within that region of the underworld.

Each of the top middle registers contains creatures and items typical of the Egyptian underworld, while the bottom registers contain additional information or details represented pictorially regarding the specific hour.[4] The middle horizontal register traditionally starts with Ra on his solar barque (a type of boat), entering a new realm or ‘hour’ of the underworld.

Throughout the text of the Amduat, Ra is depicted as being "ram-headed" as he descends into the underworld and becomes separated from his body, being left only with his 'Ba' as he seeks to reunite with his body, which is now in the form of Osiris, in the ensuing hours. The hieroglyph for Ba is the same as the one for a ram in Ancient Egyptian, suggesting that his appearance is a visual pun.[3]

The Egyptian underworld is often depicted as being the place of death, but also renewal for many deities and the souls that pass through. As such, it is often known as a 'place of opposites,' which is best represented in hour 5 with the waters of Nun (the river that in the underworld is called the 'Wernes', but is the Nile in the land of the living) intermingling with the desert sands of Sokar.[4][7] Here, it can be seen that life and death are meeting within the underworld, creating a chaos that only the influence of Maat can control. Maat is the deity of truth, order, and most importantly control, so she is often seen alongside the deceased pharaoh or Ra as they continue the normal order of the suns path daily, depicted most often as her signature feather.

Maat is also an important goddess for the pharaoh due to her representing order, as it was expected for the pharaoh to invoke Maat to keep order over the kingdom of Egypt, thereby also pushing away chaos and disorder. Her inclusion on the journey of the sun's setting and eventual rebirth once more may suggest that this is the order of the world and that is therefore overseen by her.[3]

Additionally, the depiction of the Amduat is not just tied to the wall carvings within a tomb, as the tombs themselves are often a part of representing the Amduat in its entirety.[4] Thutmose III's tomb is a very well preserved example of how the Amduat should be physically and pictorially represented, setting the example for the pharaohs that came after him.[6]

The hours

Hour 1: The sun god enters from the western horizon (akhet) which is a transition between day and night. Just below the image of Ra in his solar bargue is the alternate depiction of the sungod as a scarab in a smaller barque. This is the god Khepri, who Ra turns into once the sun rises once more and is likely depicted in hour 1 as the sun begins to set for the night. The upper and lower registers contain a labeled list of the common and/or important creatures and beings found within the underworld.[3] Two depictions of the goddess Maat are present leading Ra's barque, possibly showing how her order is still present even in the chaos of the underworld.[8]

Hour 2: This is when Ra officially enters the underworld on his barque along with four other boats beside him, leaving the transition between life & death or between day & night. This region of the underworld is categorized by its representation of the primeval waters of Nun as a body of water called 'Wernes'.[7][4] Maat is once more depicted, though now only as her symbol of a curved feather on one of the boats, and is supported by an unnamed being. This hour stresses fertility, represented both by the waters of Nun and the unnamed gods of the lower register who are all associated with images of agriculture and farming.[7]

Hour 3: In this region, the waters of Nun are now transformed into the 'Waters of Osiris,' and is marked by Osiris being visually represented on the lower register. Ancient Egyptians believed that the Nile was sourced from the underworld, and so Osiris's inclusion at this point of the journey makes sense when considering he is the god of the afterlife, as well as fertility and agriculture.[9] There are still four boats just as there were in the second hour, but there is no clear depiction of the god Ra on any of them, with the text of the Amduat stating that Ra was split between them.[9]

Hour 4: Ra reaches Imhet, the barren desert land of Sokar, the underworld hawk deity. At this point, the sungod has reached deep enough into the underworld and away from his own light that he cannot see, having to rely on his own voice as a way to guide himself and his crew out of the darkness.[10][4] Without any water to traverse, the solar barque turns into a double-headed, fire-breathing serpent as Ra's only means to traverse this pitch-black and sandy region. This hour is particularly notable for the visual break it takes from the other hours in that it has a giant sand path 'zig-zag' through all three registers, uniting them all, but making it hard for Ra to traverse on account of the various doors in the way.[10]

Hour 5: The land of Sokar continues into this hour, as does the serpent-barque. This is the region of opposites, seen in the waters of Nun uniting with the desert lands of Sokar. Osiris's burial mound is seen on the top register with Khepri crawling out, representing the eventual rebirth of Ra that begins with recovering the body of Osiris.[11] There is a narrow passage-way that it is attempting to get through, resulting in all of the friendly beings of this regions (including the scarab representation of Khepri) helping to pull the boat. An oval representing the 'Cavern of Sokar' is present on the bottom register with the god himself being contained by a lake of fire surrounding the cavern.[11]

Hour 6: This is when the most significant event in the underworld occurs. The body of the sungod (or possibly the body of Osiris no longer mummiform) is seen with Khepri's scarab form, being protected by the serpent of Mehen as he regenerates. The Mehen serpent at this point joins the journey, staying with him through the rest of the hours.[12] Once again, Ra's solar barque travels the waters of Nun as regenerative power flows, helping to revitalize the Ba of Ra as it is reunited with his body in the form of Osiris.[4] This renews the light of the sun in this hour, represented as a sun-disc crown appearing on Ra's head. Additionally, representations of the kings of lower and upper Egypt are found here as the recently deceased king must face his predecessors before being reborn himself.[12]

Hour 7: Regenerating the light of Ra is a very dangerous moment in the journey, as it attracts the forces of evil present in the underworld. In this hour, Apep swallows all of the waters of Nun in an attempt to stop the barque and kill Osiris through Ra once more, preventing the daily cycle of the sun.[13] The goddess Isis places a magic spell upon the barque in order to allow it to continue traveling through the regions without the need for water. On the upper register, the enemies of Osiris are punished for their intent to cause him harm, and the lower register contains humanized depictions of the stars following Ra's path to the end of the underworld.[13]

Hour 8: Ra has been fully regenerated and the powers of evil have been avoided through the help of the gods. Now, Ra comes across 5 doors that he must command open with his voice, adding to the hardships on this journey.[14] The unnamed gods on the upper and lower registers are seen creating new clothing, again associated with ideas of rebirth and renewal. The solar barque is pulled along by 8 unnamed gods to help Ra reach the surface once more. [14]

Hour 9: Ra's solar barque is pulled by 12 oarsmen in this hour, helping to pull him towards the light of the living world. The three idols present in front of the men are there to help the gods carrying stalks of grain disperse bread and beer to the dead in the underworld. No further explanation is offered in the text as to why this is done, but is likely tied to the ideas of the deceased 'living' in the underworld, and therefore still require sustenance.[15]

Hour 10: Ra continues his journey, being protected by his 12 oarsmen who now carry weapons to protect against any enemies, but especially against Apep. On the lower register is an image of those who drowned in water being pulled to shore by Horus, the god of the sky (in addition to many other things).[16] This is a comforting image as it was believed in Ancient Egypt that those who did not receive a proper burial could never reach the underworld or eternal life, and so this hour of the Amduat shows that this isn't the case however, and not all hope is lost for these lost souls.[16]

Hour 11: The eyes of Ra are fully healed as a symbol of his health and rejuvenation. On the lower register, a giant serpent known as the 'World-Encircler" is brought in by a row of 12 unnamed deities. A bright red sun-disk protected by a serpent (similar to how Mehen protects Ra) has appeared on the prow of the boat at this point, showing that the time of Ra's journey through the underworld is coming to an end.[17] Horus calls upon a monstrous serpent with the unquenchable fire to destroy the enemies of his father, Osiris, by burning their corpses and cooking their souls.[17]

Hour 12: Finally, the sungod is at the end of the underworld and the end of his journey, having been reborn once again. He takes on the form of Khepri as the morning sun crests on the horizon. He is led out of the underworld by many deities and gods, the giant serpent 'World-Encircler' joining the parade as well.[18]

Once the deceased finished their journey through the underworld, they arrived at the Hall of Maat. Here they would undergo the Weighing of the Heart ceremony where their purity would be the determining factor in whether they would be allowed to enter the Kingdom of Osiris.

Amduat Tombs

Understanding Amduat tombs[19] can be just as important as understanding the hours of the Amduat as there are instructions at the end of the Amduat text on how it should be presented within a tomb. This implies that the physical representation of it is just as important as the pictorial representation in guiding the deceased to the afterlife alongside Ra.

Amduat tombs are associated with the beginning of the New Kingdom of Egypt, and became popular with the construction of the Tomb of Thutmose III, who ruled halfway through the Eighteenth Dynasty. Being found in the Valley of the Kings, his tomb follows the architectural tradition of being a subterranean monument, shaped in what Egyptologist Josh Roberson calls a “curved and bent axe” style.[6] Following that style, it can be seen in the corresponding image that Thutmose III's tomb contained his burial chamber which was connected to four storage rooms, an antechamber, a well shaft, and three connected corridors leading out to the entrance.

There are many possible reasons for this style growing in popularity, likely tied to the various symbolic interpretations of the rooms found within the tomb. There are no agreed upon descriptions for the purposes of these rooms and what was contained inside of them, with historians like Erik Hornung and Friedrich Abitz attempting to explain them in their respective academic pursuits.

The Tomb of Thutmose III

As discussed by Historians Catherine Roehrig and Barbara Richter, the architecture of Thutmose III's tomb is likely meant to mirror the structure of the underworld as the Amduat displays it.[4] Found within the burial chamber of the pharaoh, the Amduat was a guide for him to follow through the underworld, as well as a way to achieve rebirth for himself after death. This may be why the structure of the tomb itself slopes downwards and winds around, to form that bent shape, as historians theorize that it may reflect the confusing and labyrinthian structure of the underworld itself. [4][6]

It begins by starting on the west side of the room, and ending to the east side of the room in order to mirror the cycle of the sun. The Amduat ending on the east side of the room lines up with the sun rising in the east, representing the rebirth and renewal that the pharaoh hoped to achieve at the end of his journey. The hours are out of order on the walls however, with hours 5 and 6 being placed between hours 1 and 12.[5] This may be a representation of a spiral design, as someone who views the Amduat in numerical order will have to complete an irregular circle throughout the room, again being associated with ideas of a continual cycle.[4]

Additionally, the rounded corners of the room create an oval shape which has many interpretations: it may represent the continual, circular life cycle of the sun's journey,[5] or may line up with the rounded corner edge of the actual illustrated Amduat present on the walls.[6] Connections to the oval (or cartouche-shaped)[6] cavern of Sokar in the 6th hour may also be present in the oval burial chamber and sarcophagus of Thutmose III and connect to ideas of rebirth or renewal that the pharaoh wished to achieve for himself.[4] His sarcophagus, found in the center of the burial chamber, is similarly oval-shaped as well, including his name which is within a royal cartouche. [4]

Other Examples of Amduat Tombs

The vizier to Thutmose III, Useramun, was a rare example of someone not of royal-birth having their tomb in the Amduat style. This may be due to many reasons, but shows how exclusive royal tombs were to the pharaoh and his immediate family. It is notable that Useramun's tomb only contained the images of hours 3 and 4, not the whole journey of the sun which only adds to the exclusivity of the Amduat to royalty in Ancient Egyptian funerary traditions.

Amenhotep II (KV 35) and Amenhotep III (KV 22) both have examples of completed Amduat texts within their burial tombs as well, following many of the conventions that Thutmose III began within his tomb.

Later Eighteenth Dynasty tombs strayed away from this approach to follow a more linear design style, being arranged by a single long corridor and straightening out the previously ‘bent axe’ style of earlier pharaohs.[6] The Amduat was still present in these tombs, though was not only reserved for the burial chambers, as it was depicted throughout the various parts of the tomb. Additionally, with the rise of the Ramesside Period in the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt, the Amduat began to appear alongside other funerary texts like The Book of Gates and The Book of Caverns as expansions of the mythos of the Egyptian Underworld.[6]

At the end of the New Kingdom, the Amduat seems to have lost its exclusivity, appearing on both coffins and papyri for deceased people of a lower class than royalty or nobility. [5]

Gallery

-

Partial image of the 5th hour of the Amduat depicting Osiris within the cavern (Tomb of Thutmose III, Valley of the Kings)

-

Hours 9 and 10 of the Amduat (Cat. 1776, Museo Egizio)

-

Hour 11 of the Amduat (Cat. 1776, Museo Egizio)

-

Full image of hour 12 of the Amduat (Cat. 1776, Museo Egizio)

Notes

- ^ Forman and Quirke (1996), p. 117.

- ^ a b c Hornung, Erik; Lorton, David (1999). The ancient Egyptian books of the afterlife. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8014-3515-7.

- ^ a b c d Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Richter, Barbara A. (2008). "The Amduat and Its Relationship to the Architecture of Early 18th Dynasty Royal Burial Chambers". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 44: 73–104. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 27801622.

- ^ a b c d e Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the Afterlife: The Egyptian Amduat - A Quest for Immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Roberson, Joshua. "The Rebirth of the Sun: Mortuary Art and Architecture in the Royal Tombs of New Kingdom Egypt". Expedition Magazine. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ a b c Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. p. 25. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 58–61. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 68–73. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 80–85. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 90–95. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 102–105. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Abt, Theodor; Hornung, Erik (2003). Knowledge for the afterlife: the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (First ed.). Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. pp. 140–143. ISBN 978-3-9522608-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Roberson, Joshua. "The Rebirth of the Sun: Mortuary Art and Architecture in the Royal Tombs of New Kingdom Egypt". Expedition Magazine. p. 15-16. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

References

- Forman, Werner and Stephen Quirke. (1996). Hieroglyphs and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2751-1.

- Erik Hornung trans. David Lorton (1999). The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press.

- Hornung, Erik; Abt, Theodor (editors): The Egyptian Amduat. The Book of the Hidden Chamber. English translation by David Warburton, revised and edited by Erik Hornung and Theodor Abt. Living Human Heritage Publications, Zurich 2007. (Images, hieroglyphs, transcription and English translation).

- Knowledge for the Afterlife - the Egyptian Amduat - a quest for immortality (1963), Theodore Abt and Erik Hornung, Living Human Heritage.