165th Rifle Division

| 165th Rifle Division (July 8, 1940 - December 27, 1941) 165th Rifle Division (December 1941 - June 1946) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1940–1946 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Battle of Kiev (1941) Battle of Lyuban Battle of Nevel (1943) Operation Bagration Lublin–Brest offensive Vistula–Oder offensive East Pomeranian offensive Battle of Berlin |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Siedlce (2nd Formation) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Ivan Vasilevich Zakharevich Col. Pavel Ivanovich Solenov Col. Vasilii Ivanovich Morozov Col. Nikolai Ivanovich Kaladze |

The 165th Rifle Division was originally formed as an infantry division of the Red Army in the North Caucasus Military District in July 1940, based on the shtat (table of organization and equipment) of September 13, 1939. It was still in that District at the time of the German invasion, and it was soon moved to the vicinity of Kyiv as part of Southwestern Front. It would remain defending south of the Ukrainian capital into September, eventually as part of 37th Army, when it was deeply encircled and destroyed.

A new 165th was created in January 1942 in the Ural Military District based on a 400-series division that began forming the previous month. After forming up until April it was sent west by rail where it was assigned to Leningrad Front.

1st Formation

The division first began forming on July 8, 1940, at Ordzhonikidze in the North Caucasus Military District. Its order of battle on June 22, 1941, was as follows:

- 562nd Rifle Regiment

- 641st Rifle Regiment

- 751st Rifle Regiment

- 608th Artillery Regiment[1]

- 199th Antitank Battalion

- 451st Antiaircraft Battalion

- 199th Reconnaissance Battalion

- 206th Sapper Battalion

- 305th Signal Battalion

- 164th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 153rd Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Platoon

- 199th Motor Transport Battalion

- 155th Field Postal Station

- 41st Field Office of the State Bank

Col. Ivan Vasilevich Zakharevich took command of the division on July 16, where he would remain for the duration of the 1st formation. At the start of the German invasion it was part of 64th Rifle Corps, with the 175th Rifle Division.[2] After a brief period to complete its mobilization it began moving by rail, with its Corps, toward the front in early July, concentrating at Rudnevka by July 12.[3] 64th Corps was now in the reserves of Southwestern Front.[4]

Defense of Kyiv

The 13th and 14th Panzer Divisions reached the Irpin River west of Kyiv on July 11 after breaking through Southwestern Front near Zhytomyr. The German command was divided on plans to directly attack Kyiv to seize its crossings over the Dniepr River, but by July 13 German reconnaissance made it clear that Soviet fortifications and troop concentrations ruled out any possibility of taking the city by surprise. Kyiv would remain in Soviet hands for more than two further months. At about the same time the 64th Corps moved into positions along the Irpin, with the 175th west and southwest of Boiarka, and the 165th further southwest.[5] In Order No. 034/op of August 1 the commander of the Southwestern Direction, Marshal S. M. Budyonny, wrote:

For a long time now, the 64th Rifle Corps has been demonstrating low combat effectiveness. Both divisions of this corps, and especially the 165th, leave the battlefield at the first appearance of the enemy. On July 31, the 165th division again failed to fulfil its combat mission and retreated to the Vasilkov line.[6]

During late July and into early August the XXIX Army Corps of German 6th Army made numerous attempts to capture Kyiv, but all of these were foiled. As German forces advanced on Boiarka 64th Corps was split apart, with the 165th pushed across the Dniepr and the 175th falling back by August 11 into the Kiev Fortified Region, defending the city's southwestern sector.[7] As of the beginning of the month the Corps was being disbanded and the 165th came under direct command of Southwestern Front. Later in August it was subordinated to the new 37th Army,[8] which was tasked with continuing the defense of Kyiv. Meanwhile, the 2nd Panzer Group and 2nd Army of Army Group Center began their drives southward. By September 10 the remnants of 5th and 37th Armies were grouped north of Kozelets but on September 16 the 2nd Panzer linked up with the 1st Panzer Group of Army Group South well to the east and the Army was deeply encircled.[9] As of September 15 the 165th had been effectively destroyed, but in common with most of the encircled divisions of Southwestern Front it officially remained on the books until December 27, when it was finally written off.

2nd Formation

The 436th Rifle Division began forming in December 1941 until January 23, 1942 at Kurgan in the Ural Military District. On the latter date it was redesignated as the new 165th Rifle Division.[10] Its order of battle was very similar to that of the 1st formation:

- 562nd Rifle Regiment

- 641st Rifle Regiment

- 751st Rifle Regiment

- 608th Artillery Regiment[11]

- 199th Antitank Battalion

- 199th Reconnaissance Company

- 202nd Sapper Battalion

- 305th Signal Battalion (later 305th Signal Company)

- 164th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 533rd Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Platoon

- 199th Motor Transport Company

- 149th Field Bakery

- 914th Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 1670th Field Postal Station

- 1091st Field Office of the State Bank

Col. Pavel Ivanovich Solenov was appointed to command on the date of redesignation. The division remained forming and training in the Ural District into April, when it began moving west by rail, joining the 6th Guards Rifle Corps in Leningrad Front by the beginning of May.[12] When it left the Urals the 165th was at full strength with over 12,000 officers and enlisted personnel allotted.[13] It joined the active army on May 7.

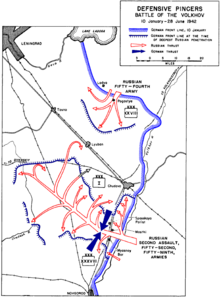

Battle of Lyuban

By late April the Red Army's winter counteroffensive had wound down to a halt from sheer exhaustion without many of the STAVKA's objectives being attained. One of these was breaking the siege of Leningrad. 2nd Shock and 54th Armies attempted to break through to the city from the south and east beginning in early January but 2nd Shock had become immobilized in a deep salient without reaching the initial objective of Lyuban. By May it was necessary to rescue the Army from its predicament in the forests and thawing swamps. It had been encircled in late March, but soon partially relieved when a narrow corridor was forced through the German lines near Miasnoi Bor. This route became practically useless when it was flooded by the spring rains.[14]

On April 30 the commander of the recently-designated Volkhov Group of Forces, Lt. Gen. M. S. Khozin, ordered the commander of 2nd Shock, Lt. Gen. A. A. Vlasov, to take up an all-round defense. Meanwhile, Khozin began planning for a new operation to enlarge the corridor between Miasnoi Bor and Spasskaya Polist, which was submitted to the STAVKA on May 2. To this end the 6th Guards Corps was to be reinforced with the 4th and 24th Guards Rifle Divisions plus the 24th and 58th Rifle Brigades, all of which required refitting, which was to be completed by mid-May. The Corps was then to widen the corridor, reinforce 2nd Shock, and join in a combined attack with 59th Army to encircle and eliminate the German forces in the Chudovo area. On May 12 Khozin reported that German reinforcements were arriving at Spasskaya Polist and north of Lyubtsy, which seemed to indicate another effort would be made to cut 2nd Shock's communications. He now directed Vlasov to prepare for a breakout operation by stages.[15]

The breakout battle began on May 16 and continued for several days, but proved largely futile, at significant cost to both those inside and outside the pocket. At 1720 hours on May 21 the STAVKA sent orders for 2nd Shock to break out once and for all and to clear German forces from the east bank of the Volkhov River at Kirishi and Gruzino no later than June 1. Also on May 21 orders arrived to send 6th Guards Corps, minus the 165th, to reinforce Northwestern Front's operations in the Demyansk region. By now, 2nd Shock had lost as much as 70 percent of its original strength and was lacking all types of supplies. On May 24 it began the first phase of its withdrawal from its most advanced positions, and Army Group became alarmed that it might escape. To this end, on May 30 the XXXVIII and I Army Corps launched a joint attack to finally cut the corridor to the pocket. This was complete by noon on May 31st.[16] In a desperate effort to reopen the gap the 165th was thrown into battle near Miasnoi Bor on June 1, without artillery support, and soon lost 50 percent of its combat strength without any success. The division would remain effectively crippled for many months to come, and on June 17 Khozin removed Colonel Solenov from command, replacing him with Col. Vasilii Ivanovich Morozov, who had been leading the 58th Rifle Brigade.[17]

References

Citations

- ^ Charles C. Sharp, "Red Legions", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed Before June 1941, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. VIII, Nafziger, 1996, p. 81

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 12

- ^ Sharp, "Red Legions", p. 82

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 24

- ^ David Stahel, Kiev 1941, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2012, pp. 77-80

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140101052005/http://bdsa.ru/documents/html/donesaugust41/410801.html. In Russian. Retrieved August 22, 2024

- ^ Stahel, Kiev 1941, pp. 81, 84-85

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, pp. 33, 43

- ^ Stahel, Kiev 1941, pp. 210, 228-29

- ^ Walter S. Dunn Jr., Stalin's Keys to Victory, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2007, p. 99

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed From 1942 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. X, Nafziger, 1996, p. 66

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, pp. 76, 81

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", p. 66

- ^ David M. Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941 - 1944, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2002, pp. 177-78, 182, 189-91

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941 - 1944, pp. 191-96

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941 - 1944, pp. 198-99, 201-03

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20110813111828/http://generalvlasov.ru/documents/zapiska-o-srive-boevoi-operacii-voisk-2-udarnoi-armii.html. In Russian. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

Bibliography

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. p. 81

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 189–90