Trial

| Criminal procedure |

|---|

| Criminal trials and convictions |

| Rights of the accused |

| Verdict |

| Sentencing |

|

| Post-sentencing |

| Related areas of law |

| Portals |

|

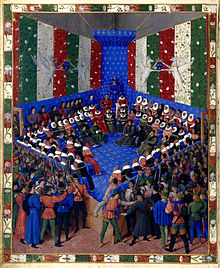

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, which may occur before a judge, jury, or other designated trier of fact, aims to achieve a resolution to their dispute.[1]

Types by finder of fact

Where the trial is held before a group of members of the community, it is called a jury trial. Where the trial is held solely before a judge, it is called a bench trial.[2] Hearings before administrative bodies may have many of the features of a trial before a court, but are typically not referred to as trials. An appeal (appellate proceeding) is also generally not deemed a trial, because such proceedings are usually restricted to a review of the evidence presented before the trial court, and do not permit the introduction of new evidence.

Types by dispute

Criminal

A criminal trial is designed to resolve accusations brought (usually by a government) against a person accused of a crime. In common law systems, most criminal defendants are entitled to a trial held before a jury. Because the state is attempting to use its power to deprive the accused of life, liberty, or property, the rights of the accused afforded to criminal defendants are typically broad. The rules of criminal procedure provide rules for criminal trials.

Civil

A civil trial is generally held to settle lawsuits or civil claims—non-criminal disputes. In some countries, the government can both sue and be sued in a civil capacity. The rules of civil procedure provide rules for civil trials.

Administrative

Although administrative hearings are not ordinarily considered trials, they retain many elements found in more "formal" trial settings. When the dispute goes to a judicial setting, it is called an administrative trial, to revise the administrative hearing, depending on the jurisdiction. The types of disputes handled in these hearings are governed by administrative law and auxiliarily by civil trial law.

Labor

Labor law (also known as employment law) is the body of laws, administrative rulings, and precedents which address the legal rights of, and restrictions on, working people and their organizations. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, employer, and union. Individual labour law concerns employees' rights at work also through the contract for work. Employment standards are social norms (in some cases also technical standards) for the minimum socially acceptable conditions under which employees or contractors are allowed to work. Government agencies (such as the former US Employment Standards Administration) enforce labour law (legislature, regulatory, or judicial).

Systems

Adversarial

In common law systems, an adversarial or accusatory approach is used to adjudicate guilt or innocence. The assumption is that the truth is more likely to emerge from the open contest between the prosecution and the defense in presenting the evidence and opposing legal arguments, with a judge acting as a neutral referee and as the arbiter of the law. In several jurisdictions in more serious cases, there is a jury to determine the facts, although some common law jurisdictions have abolished the jury trial. This polarizes the issues, with each competitor acting in its own self-interest, and so presenting the facts and interpretations of the law in a deliberately biased way.

The intention is that through a process of argument and counter-argument, examination-in-chief and cross-examination, each side will test the truthfulness, relevancy, and sufficiency of the opponent's evidence and arguments. To maintain fairness, there is a presumption of innocence, and the burden of proof lies on the prosecution. Critics of the system argue that the desire to win is more important than the search for truth. Further, the results are likely to be affected by structural inequalities. Those defendants with resources can afford to hire the best lawyers. Some trials are—or were—of a more summary nature, as certain questions of evidence were taken as resolved (see handhabend and backberend).[3][4][5]

Inquisitorial

In civil law legal systems, the responsibility for supervising the investigation by the police into whether a crime has been committed falls on an examining magistrate or judge who then conducts the trial. The assumption is that the truth is more likely to emerge from an impartial and exhaustive investigation, both before and during the trial itself. The examining magistrate or judge acts as an inquisitor who directs the fact-gathering process by questioning witnesses, interrogating the suspect, and collecting other evidence.

The lawyers who represent the interests of the state and the accused have a limited role to offer legal arguments and alternative interpretations to the facts that emerge during the process. All the interested parties are expected to cooperate in the investigation by answering the magistrate or judge's questions and, when asked, supplying all relevant evidence. The trial only takes place after all the evidence has been collected and the investigation is completed. Thus, most of the factual uncertainties will already be resolved, and the examining magistrate or judge will already have resolved that there is prima facie of guilt.

Critics argue that the examining magistrate or judge has too much power with the responsibilities of both investigating and adjudicating on the merits of the case. Although lay assessors do sit as a form of jury to offer advice to the magistrate or judge at the conclusion of the trial, their role is subordinate. Further, because a professional has been in charge of all aspects of the case to the conclusion of the trial, there are fewer opportunities to appeal the conviction alleging some procedural error.[6]

Mistrials

A judge may cancel a trial prior to the return of a verdict; legal parlance designates this as a "mistrial". A judge may declare a mistrial due to:

- The court determining that it lacks jurisdiction over a case.

- Evidence being admitted improperly, or new evidence that might seriously affect the outcome of the trial being discovered.

- Misconduct by a party, juror,[7] or an outside actor, if it prevents due process.

- A hung jury which cannot reach a verdict with the required degree of unanimity. In a criminal trial, if the jury is able to reach a verdict on some charges but not others, the defendant may be retried on the charges that led to the deadlock, at the discretion of the prosecution.

- Disqualification of a juror after the jury is empaneled, if no alternative juror is available and the litigants do not agree to proceed with the remaining jurors, or the remaining jurors not meeting the required number for a trial.

- The illness or death of a juror or attorney.

Either side may submit a motion for a mistrial; on occasion, the presiding judge may declare one on a motion of their own. If a mistrial is declared, the case at hand may be retried at the discretion of the plaintiff or prosecution, as long as double jeopardy does not bar that party from doing so.

Other types

Some other kinds of processes for resolving conflicts are also expressed as trials. For example, the United States Constitution requires that, following the impeachment of the president, a judge, or another federal officer by the House of Representatives, the subject of the impeachment may only be removed from office by an impeachment trial in the Senate. In earlier times, disputes were often settled through a trial by ordeal, where parties would have to endure physical suffering in order to prove their righteousness; or through a trial by combat, in which the winner of a physical fight was deemed righteous in their cause.

See also

References

- ^ Schultz, Norman. Fact-Finding. Accessed 17 November 2008

- ^ Black, Henry Campbell (1990). Black's Law Dictionary, 6th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing. pp. 156. ISBN 0-314-76271-X.

- ^ Hale, Sandra Beatriz (July 2004). The Discourse of Court Interpreting: Discourse Practices of the Law, the Witness and the Interpreter. John Benjamins. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-58811-517-1.

- ^ Richards, Edward P.; Katharine C. Rathbun (1999-08-15). Medical Care Law. Jones & Bartlett. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8342-1603-7.

- ^ Care, Jennifer Corrin (2004-01-12). Civil Procedure and Courts in the South Pacific. Routledge Cavendish. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-85941-719-5.

- ^ See:

- (in Italian) Antonia Fiori, "Quasi denunciante fama : note sull’introduzione del processo tra rito accusatorio e inquisitorio", in Der Einfluss der Kanonistik auf die europäische Rechtskultur, 3. Strafrecht und Strafprozeß, ed. O. Condorelli, Fr. Roumy, M. Schmoeckel; Cologne, Weimar, Vienna, 2012, p. 351–367

- Richard M. Fraher, "IV Lateran's Revolution in Criminal Procedure: the Birth of inquisitio, the End of Ordeals and Innocent III's Vision of Ecclesiastical Politics", in Studia in honorem eminentissimi cardinalis Alphonsi M. Stickler, ed. Rosalius Josephus Castillo Lara. Rome: Salesian Pontifical University (Pontificia studiorum universitas salesiana, Facilitas juris canonici, Studia et textus historie juris canonici, 7), 1992, p. 97–111

- (in German) Lotte Kéry, "Inquisitio-denunciatio-exceptio: Möglichkeiten der Verfahrenseinleitung im Dekretalenrecht, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte, Kanonistische Abteilung, 87, 2001, p. 226–268.

- (in French) Julien Théry, "fama : L’opinion publique comme preuve. Aperçu sur la révolution médiévale de l'inquisitoire (XIIe–XIVe s.)", in La preuve en justice de l'Antiquité à nos jours, ed. Br. Lemesle. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2003, p. 119–147, online].

- Julien Théry, "Judicial Inquiry as an Instrument of Centralized Government: The Papacy’s Criminal Proceedings against Prelates in the Age of Theocracy (mid-12th to mid-14th century)", in Proceedings of the 14th International Congress of Medieval Canon Law, Vatican City, 2016, p. 875–889.

- (in German) Winfried Trusen, "Der Inquisitionsprozess : seine historischen Grundlagen und frühen Formen", Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte, Kanonistische Abteilung, 74, 1988, p. 171–215

- ^ St. Eve, Amy J.; Zuckerman, Michael A. (2012). "Ensuring an Impartial Jury in the Age of Social Media" (PDF). Duke Law & Technology Review. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on Aug 9, 2017.