Royal Game of Ur

One of the five gameboards found by Sir Leonard Woolley in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, now held in the British Museum[1] | |

| Years active | Earliest boards date to c. 2600 – c. 2400 BC[a] during the Early Dynastic III, being played popularly in the Middle East through late antiquity and in Kochi, India through the 1950s |

|---|---|

| Genres | |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | 10–30 seconds |

| Playing time | Usually around 30 minutes |

| Chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics, counting, probability |

| Synonyms |

|

The Royal Game of Ur is a two-player strategy race board game of the tables family that was first played in ancient Mesopotamia during the early third millennium BC. The game was popular across the Middle East among people of all social strata, and boards for playing it have been found at locations as far away from Mesopotamia as Crete and Sri Lanka. One board, held by the British Museum, is dated to c. 2600 – c. 2400 BC, making it one of the oldest game boards in the world.[2]

The Royal Game of Ur is sometimes equated to another ancient game which it closely resembles, the Game of Twenty Squares.

At the height of its popularity, the game acquired spiritual significance, and events in the game were believed to reflect a player's future and convey messages from deities or other supernatural beings. The Game of Ur remained popular until late antiquity, when it stopped being played, possibly evolving into, or being displaced by, a form of tables game. It was eventually forgotten everywhere except among the Jewish population of the Indian city of Kochi, who continued playing a version of it called 'Asha' until the 1950s when they began emigrating to Israel.[3]

The Game of Ur received its name because it was first rediscovered by the English archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley during his excavations of the Royal Cemetery at Ur between 1922 and 1934. Copies of the game have since been found by other archaeologists across the Middle East. A partial description in cuneiform of the rules of the Game of Ur as played in the second century BC has been preserved on a Babylonian clay tablet written by the scribe Itti-Marduk-balāṭu.

Based on this tablet and the shape of the gameboard, Irving Finkel, a British Museum curator, reconstructed the basic rules of how the game might have been played. The object of the game is to run the course of the board and bear all one's pieces off before one's opponent. Like modern backgammon, the game combines elements of both strategy and luck.

History

The Game of Ur was popular across the Middle East[4][6] and boards for it have been found in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Cyprus and Crete.[4][6][7] Four gameboards bearing a very close resemblance to the Royal Game of Ur were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.[8] These boards came with small boxes to store dice and game pieces[8] and many had senet boards on the reverse sides so that the same board could be used to play either game and merely had to be flipped over.[8]

The game was popular among all social classes.[4] A graffito version of the game carved with a sharp object, possibly a dagger, was discovered on one of the human-headed winged bull gate sentinels from the palace of Sargon II (721–705 BC) in the city of Khorsabad.[4][5]

The Game of Ur eventually acquired superstitious significance[4][9] and the tablet of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu provides vague predictions for the players' futures if they land on certain spaces,[4][9] such as "You will find a friend", "You will become powerful like a lion", or "You will draw fine beer".[4][9] People saw relationships between a player's success in the game and their success in real life.[4][9] Seemingly random events, such as landing on a certain square, were interpreted as messages from deities, ghosts of deceased ancestors, or from a person's own soul.[9]

A 2013 study of nearly one hundred well-dated game boards across the Near East shows significant changes over 1,200 years of time in the layout of squares on the board.[7] This indicates that game rules and game play were not static, but changed over time. The study further shows the game was transmitted from Mesopotamia to the Levant around 1800 BC, from the Levant to Egypt around 1600 BC where it picked up small innovations in board design (additional squares), and from Egypt or the Levant to Cyprus and Nubia. Several apparently failed innovations in board design also appear (i.e., only one example of a specific board design is known from the archaeological record).[7]

It is unclear what led to the Game of Ur's eventual decline during late antiquity.[9] One theory holds that it evolved into backgammon;[9] whereas another holds that early forms of backgammon eclipsed the Game of Ur in popularity, causing players to eventually forget about the older game.[4][9] At some point before the game fell out of popularity in the Middle East, it was apparently introduced to the Indian city of Kochi by a group of Jewish merchants.[4][9]

Members of the Jewish population of Kochi were still playing a recognizable form of the Game of Ur, which they called Aasha,[3] by the time they started emigrating to Israel in the 1950s after World War II.[4][9] The Kochi version of the game had twenty squares, just like the original Mesopotamian version, but each player had twelve pieces rather than seven, and the placement of the twenty squares was slightly different.[4]

Modern rediscovery

The British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley discovered five gameboards of the Game of Ur during his excavation of the Royal Cemetery at Ur between 1922 and 1934.[6][8][9] Because the game was first discovered in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, it became known as the "Royal Game of Ur", but later archaeologists uncovered other copies of the game from other locations across the Middle East.[9] The boards discovered by Woolley date to around 2,600–2,400 BC.[2][10][b]

All five boards were of an identical type, but they were made of different materials and had different decorations.[6][8] Woolley reproduced images of two of these boards in his 1949 book, The First Phases.[6][8] One of these is a relatively simple set with a background composed of discs of shell with blue or red centers set in wood-covered bitumen.[6][8] The other is a more elaborate one completely covered with shell plaques, inlaid with red limestone and lapis lazuli.[6][8] Other gameboards are often engraved with images of animals.[4][6][8]

Play

Reconstruction

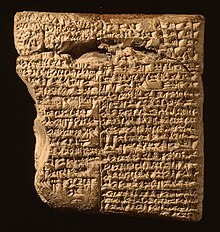

When the Game of Ur was first discovered, no one knew how it was played.[6][8][9][12] Then, in the early 1980s, Irving Finkel, a curator at the British Museum, translated a clay tablet written c. 177 BC by the Babylonian scribe Itti-Marduk-balāṭu describing how the game was played during that time period, based on an earlier description of the rules by another scribe named Iddin-Bēl.[9][12] This tablet was written during the waning days of Babylonian civilization,[9] long after the time when the Game of Ur was first played.[8]

It had been discovered in 1880 in the ruins of Babylon and sold to the British Museum.[12] Finkel also used photographs of another tablet describing the rules, which had been in the personal collection of Count Aymar de Liedekerke-Beaufort, but was destroyed during World War I.[12]

This second tablet was undated, but is believed by archaeologists to have been written several centuries earlier than the tablet by Itti-Marduk-balāṭu and to have originated from the city of Uruk.[12] The backs of both tablets show diagrams of the gameboard, clearly indicating which game they are describing.[4][12] Based on these rules and the shape of the gameboard, Finkel was able to reconstruct how the game might have been played.[8][9][12]

Basic rules

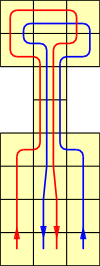

The Game of Ur is a race game[8][9][12] and it is probably an ancestor of the tables family of games that are still played today and include backgammon.[8][9] The Game of Ur is played using two sets of seven game pieces, similar to those used in draughts or checkers.[8] One set of pieces is white with five black dots and the other set is black with five white dots.[6][8] The gameboard is composed of two rectangular sets of boxes, one containing three rows of four boxes each and the other containing three rows of two boxes each, joined by a "narrow bridge" of two boxes.[12]

The gameplay involves elements of both luck and strategy.[8] Movements are determined by rolling a set of four-sided, tetrahedron-shaped dice.[6][8] Two of the four corners of each die are marked and the other two are not, giving each die an equal chance of landing with a marked or unmarked corner facing up.[6][8] The number of marked ends facing upwards after a roll of the dice indicates how many spaces a player may move during that turn.[12] A single game can last up to half an hour.[8]

The objective of the game is for a player to move all seven of their pieces along the course and off the board before their opponent.[8] On all surviving gameboards, the two sides of the board are always identical with each other, suggesting that one side of the board belongs to one player and the opposite side to the other player.[6] When a piece is on one of the player's own squares, it is safe from capture.[8]

When it is on one of the eight squares in the middle of the board, the opponent's pieces may capture it by landing on the same space, sending the piece back off the board so that it must restart the course from the beginning.[8] This means there are six "safe" squares and eight "combat" squares.[8] There can never be more than one piece on a single square at any given time, so having too many pieces on the board at once can impede a player's mobility.[8]

When a player rolls a number using the dice, they may choose to move any of their pieces on the board or add a new piece to the board if they still have pieces that have not entered the game.[8] A player is not required to capture a piece every time they have the opportunity.[8] Nonetheless, players are required to move a piece whenever possible, even if it results in an unfavorable outcome.[8]

All surviving gameboards have a colored rosette in the middle of the center row.[6][12] According to Finkel's reconstruction, if a piece is located on the space with the rosette, it is safe from capture. Finkel also states that when a piece lands on any of the three rosettes, the player gets an extra roll.[12]

In order to remove a piece from the board, a player must roll exactly the number of spaces remaining until the end of the course plus one.[8] If the player rolls a number any higher or lower than this number, they may not remove the piece from the board.[8] Once a player removes all their pieces off the board in this manner, that player wins the game.

Gambling

One archaeological dig uncovered twenty-one white balls alongside a set of the Game of Ur.[8] It is believed that these balls were probably used for placing wagers.[8] According to the tablet of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, whenever a player skips one of the boxes marked with a rosette, they must place a token in the pot.[12] If a player lands on a rosette, they may take a token from the pot.[12]

Game of Twenty

The Game of Twenty or Game of Twenty Squares is another ancient tables game similar to the Royal Game of Ur.[c] Egyptian gaming boxes often have a board for this game on the opposite side to that for the better-known game of senet. It dates roughly to the period from 1500 BC to 300 BC and is known to have been played in the region that includes Babylon, Mesopotamia and Persia, as well as Egypt. The board comprises two distinct sections; a quadrant of 3 × 4 squares, like that in the Ur game, and a row or 'arm' of 8 squares projecting from the central row of the quadrant. It has five rosettes. The rules are not precisely known but it appears likely that players entered all their 5 pieces onto the arm and aimed to bear them off from the sides of the quadrant, perhaps having contested the arm by hitting opposing pieces off.[13]

Footnotes

- ^ See, for example, one of the boards discovered by Woolley and now at the British Museum.[2]

- ^ Some earlier sources date the boards to 3,000 BC, but most recent sources, including the British Museum, date them to 2,600–2,400 BC.

- ^ Finkel (2007) sees them as the same game, whereas Parlett (2018) distinguishes them.

References

- ^ "game-board | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c game-board: Museum number 120834 at britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ a b S, Priyadershini (1 October 2015). "Traditional board games: From Kochi to Iraq". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2019 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Green, William (19 June 2008). "Big Game Hunter". Time. London. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ a b Collon, Dominique (1 July 2011). "Assyrian guardian figure". BBC History. BBC. Archived from the original on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bell, Robert Charles (1979) [1960]. Board and table games from many civilizations (Revised ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 16, 17, 21, 25. ISBN 1306356377. OCLC 868966489.

- ^ a b c Alex de Voogt; Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi; Jelmer W. Eerkens (April 2014). "Cultural Transmission in the Ancient Near East: Twenty Squares and Fifty-Eight holes". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (4): 1715–1730. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.11.008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Botermans, Jack (2008). The book of games : strategy, tactics & history. Fankbonner, Edgar Loy. New York: Sterling. pp. [1]. ISBN 9781402742217. OCLC 86069181.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Donovan, Tristan (2017). It's all a game : the history of board games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan (First ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 13–16. ISBN 9781250082725. OCLC 960239246.

- ^ Christ et al. (2016), p. 72.

- ^ "tablet | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Becker, Andrea (2007). "The Royal Game of Ur". In Finkel, Irving (ed.). Ancient Board Games in Perspective: Papers from the 1990 British Museum Colloquium, with Additional Contributions. London, England: British Museum Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780714111537. OCLC 150371733.

- ^ Parlett (2018), pp. 65–66.

Further reading

- Botermans, Jack (1988). Le Monde des jeux. Paris: Le Chêne. ISBN 978-2851085122.

- Crist, Walter, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi and Alex de Voogt (2016). Ancient Egyptians at Play: Board Games Across Borders. UK: Bloomsbury.

- Finkel, Irving (2007), "On the Royal Game of Ur," in Ancient Board Games in Perspective, ed. Irving Finkel. London: British Museum Press, pp. 16–32.

- Finkel, Irving (1991). La tablette des régles du jeu royal d'Ur. Jouer dans l'Antiquité, Catalogue de l'Exposition. Marseille: Musée d'Archéologie Méditerranéenne.

- Finkel, Irving (2005) [1995]. Games: Discover and Play Five Famous Ancient Games (3rd ed.). London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714131122

- Lhôte, Jean-Marie (1993). Histoire des jeux de société. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2080109293.

- Parlett, David (2018) [1999]. History of Board Games. Brattleboro, VT: Echo. ISBN 978-1-62654-881-7

External links

- Deciphering the world's oldest rule book – Irving Finkel – The British Museum

- Tom Scott vs Irving Finkel: The Royal Game of Ur – The British Museum

- Play the Royal Game of Ur on GouziGouza