Pancho Villa Expedition: Difference between revisions

m Robot - Speedily moving category Mexico – United States relations to Category:Mexico–United States relations per CFDS. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

|image=[[File:VillaUncleSamBerrymanCartoon.png|310px]] |

|image=[[File:VillaUncleSamBerrymanCartoon.png|310px]] |

||

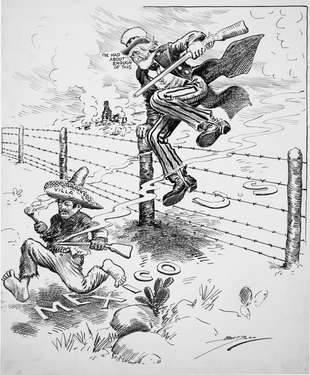

|caption=Cartoon by [[Clifford Berryman]] reflects American attitudes about the expedition |

|caption=Cartoon by [[Clifford Berryman]] reflects American attitudes about the expedition |

||

|date=1916 - 1917 |

|date=March 14, 1916 - February 7, 1917 |

||

|place=[[Northern Mexico]] |

|place=[[Northern Mexico]] |

||

|result=United States withdrawal in 1917. |

|result=Villistas dispersed, United States withdrawal in 1917. |

||

|combatant1={{flag|United States|1912}} |

|combatant1={{flag|United States|1912}} |

||

|combatant2=[[Villistas]]<br/>[[Carrancistas |

|combatant2=[[Villistas]]<br/>[[Carrancistas]] |

||

|commander1={{flagicon|United States|1912}} [[John J. Pershing]] |

|commander1={{flagicon|United States|1912}} [[John J. Pershing]]<br>{{flagicon|United States|1912}} [[George A. Dodd]]<br>{{flagicon|United States|1912}} [[Frank Tompkins]] |

||

|commander2=[[Pancho Villa]] |

|commander2=[[Pancho Villa]]<br>[[Felipe Angeles]]<br>[[Julio Cárdenas]] |

||

|strength1= |

|strength1= |

||

|strength2= |

|strength2= |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Pancho Villa Expedition'''—officially known in the United States as the '''Mexican Expedition'''<ref |

The '''Pancho Villa Expedition'''—officially known in the United States as the '''Mexican Expedition'''<ref>http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/mexex.html</ref> and sometimes colloquially referred to as the '''Punitive Expedition'''—was a [[military operation]] conducted by the [[United States Army]] against the paramilitary forces of [[Mexico|Mexican]] [[insurgent]] [[Pancho Villa|Francisco "Pancho" Villa]] from 1916 to 1917 during the [[Mexican Revolution]]. The expedition was launched in retaliation for Villa's [[Battle of Columbus (1916)|attack]] on the town of [[Columbus, New Mexico|Columbus]], [[New Mexico]] and was the most remembered event of the [[Border War (1910-1918)|Border War]]. The expeditions had one objective, to capture Villa dead or alive and put a stop to any future forays by his paramilitary forces on American soil.<ref>http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/fall/mexican-punitive-expedition-1.html</ref> The official beginning and ending dates of the Mexican Expedition are March 14, 1916 and February 7, 1917. |

||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

Trouble between the United States and Pancho Villa had been growing since 1915, when the |

Trouble between the United States and Pancho Villa had been growing since 1915, when the United States government disappointed Villa by siding with and giving its official recognition to [[Venustiano Carranza]]'s national government. Feeling betrayed, Villa began attacking American property and citizens in northern Mexico. The most serious incident occurred in January 1916, when sixteen American employees of the [[ASARCO]] company were removed from a train near [[Santa Isabel, Chihuahua|Santa Isabel]], [[Chihuahua (state)|Chihuahua]] and summarily stripped and executed. Villa kept his men south of the border to avoid a direct confrontation with the United States Army forces which were being deployed to protect the border. |

||

At approximately 4:17 am on March 9, 1916, Villa's troops attacked Columbus, New Mexico and its local detachment of the [[13th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|13th Cavalry Regiment]], killing 10 civilians and eight soldiers, and wounding two civilians and six soldiers.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca: Villa's Raid on Columbus, New Mexico |url= http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/comment/huachuca/HI1-12.htm |journal=Huachuca Illustrated |volume=1 |year=1993 |accessdate=2008-11-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1= Page, Walter Hines |last= |first= |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1916 |author2= Page, Arthur Wilson |month=April |title=The March Of Events: Making Mexico Understand |journal=[[World's Work|The World's Work: A History of Our Time]] |volume=XXXI |issue= |pages=584–593 |id= |url=http://books.google.com/?id=09_Sr9emceQC&pg=PA584 |accessdate=2009-08-04 |quote= }}</ref> The raiders also burned the town, took many horses and mules and seized available [[machine gun]]s, ammunition and merchandise, before being pursued back into Mexico. However, Villa's troops suffered considerable losses, with at least 67 dead. About 13 others would later die of their wounds. Five Mexicans were taken prisoner and later executed. The battle may have been spurred by an American merchant in Columbus who supplied Villa with weapons and ammunition. After Villa paid several thousand dollars in cash in advance, the merchant decided to stop supplying him with weapons and demanded payment in gold.{{Citation needed|date=January 2011}} |

At approximately 4:17 am on March 9, 1916, Villa's troops attacked Columbus, New Mexico and its local detachment of the [[13th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|13th Cavalry Regiment]], killing 10 civilians and eight soldiers, and wounding two civilians and six soldiers.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca: Villa's Raid on Columbus, New Mexico |url= http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/comment/huachuca/HI1-12.htm |journal=Huachuca Illustrated |volume=1 |year=1993 |accessdate=2008-11-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1= Page, Walter Hines |last= |first= |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1916 |author2= Page, Arthur Wilson |month=April |title=The March Of Events: Making Mexico Understand |journal=[[World's Work|The World's Work: A History of Our Time]] |volume=XXXI |issue= |pages=584–593 |id= |url=http://books.google.com/?id=09_Sr9emceQC&pg=PA584 |accessdate=2009-08-04 |quote= }}</ref> The raiders also burned the town, took many horses and mules and seized available [[machine gun]]s, ammunition and merchandise, before being pursued back into Mexico. However, Villa's troops suffered considerable losses, with at least 67 dead. About 13 others would later die of their wounds. Five Mexicans were taken prisoner and later executed. The battle may have been spurred by an American merchant in Columbus who supplied Villa with weapons and ammunition. After Villa paid several thousand dollars in cash in advance, the merchant decided to stop supplying him with weapons and demanded payment in gold.{{Citation needed|date=January 2011}} |

||

==Expedition== |

==Expedition== |

||

On March 15,<ref name="Marcovitz2002">{{cite book|author=Hal Marcovitz|title=Pancho Villa|url= http://books.google.com/books?id=B8ZVUEkInBEC&pg=PA66|accessdate=18 March 2011|date=March 2002| publisher=Infobase Publishing|isbn=9780791072578|page=66}}</ref> on orders from [[President of the United States|President]] [[Woodrow Wilson]], [[Major general (United States)|Major General]] [[John J. Pershing]] led an expeditionary force of 4,800 men into Mexico to capture Villa, who had already had more than a week to disperse and conceal his forces before the |

On March 15,<ref name="Marcovitz2002">{{cite book|author=Hal Marcovitz|title=Pancho Villa|url= http://books.google.com/books?id=B8ZVUEkInBEC&pg=PA66|accessdate=18 March 2011|date=March 2002| publisher=Infobase Publishing|isbn=9780791072578|page=66}}</ref> on orders from [[President of the United States|President]] [[Woodrow Wilson]], [[Major general (United States)|Major General]] [[John J. Pershing]] led an expeditionary force of 4,800 men into Mexico to capture Villa, who had already had more than a week to disperse and conceal his forces before the expedition tried to seek them out in unmapped terrain. Beginning March 19, the newly-adopted [[Curtiss JN-4]] [[fixed-wing aircraft|airplane]] was used by the [[1st Reconnaissance Squadron|1st Provisional Aero Squadron]] to conduct aerial reconnaissance.<ref name="Hurst2008">{{cite book|author=James W. Hurst|title=Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing: the Punitive Expedition in Mexico|url= http://books.google.com/books?id=mTDxfXWB7RsC&pg=PA122|accessdate=18 March 2011|year=2008|publisher =Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=9780313350047|page=122}}</ref> Pershing divided his force into two "''flying columns''" to seek out Villa, and made his main base encampment at [[Pueblo de Casas Grandes|Casas Grandes]], Chihuahua. Due to disputes with the Carranza administration over the use of the [[Mexico North Western Railway]] to supply his troops, the United States Army employed a truck-train system to convoy supplies to the encampment and the [[United States Army Signal Corps|Signal Corps]] set up [[wireless telegraph]] service from the border to Pershing's headquarters. |

||

| ⚫ | The first [[Battle of Guerrero|battle]] between the Villistas and the expedition occurred on March 29, 1916, at San Geronimo Ranch, near the town of [[Vicente Guerrero|Guerrero]]. After a long march through the [[Sierra Madre Occidental|Sierra Madre]], [[Colonel]] [[George A. Dodd]] and his command of 370 men, from the [[7th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|7th Cavalry]], launched what was called the "''last true [[charge#cavalry charges|cavalry charge]]''" in history. During the five hour battle, Pancho Villa lost over seventy-five of his men killed or wounded and he was forced to retreat into the mountains. Only five of the Americans were hurt, none of them fatally. The battle is considered the single most successful engagement of the expedition and it was the closest Pershing's men came to capturing Villa.<ref>http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/2-7cav.htm</ref><ref>Boot, pg. 199</ref><ref>Beede, pg. 218-219</ref><ref>Boot, pg. 199</ref><ref>http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/mexico_pershing.htm</ref> |

||

Pershing divided his force into two columns to seek out Villa, and made his main base encampment at [[Pueblo de Casas Grandes|Casas Grandes]], Chihuahua. Due to disputes with the Carranza administration over the use of the [[Mexico North Western Railway]] to supply his troops, the United States Army employed a truck-train system to convoy supplies to the encampment and the [[United States Army Signal Corps|Signal Corps]] set up [[wireless telegraph]] service from the border to Pershing's headquarters. |

|||

| ⚫ | On April 12, 1916, about 100 men of the 13th Cavalry were [[Battle of Parral|attacked]] by an estimated 500 Mexican troops as they were leaving the town of [[Parral, Chihuahua|Parral]]. The American commander, Colonel [[Frank Tompkins]], knew he could not win a conventional engagement, so in a running battle he and his men were able to retreat to a fortified village nearby while repulsing Mexican cavalry charges at the same time. Two Americans were killed in the fight and another six were wounded, the Mexicans lost between fourteen and seventy men according to conflicting accounts.<ref>Boot, pg. 201-203</ref><ref>http://www.cabq.gov/veterans/history/worldwari</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The first [[Battle of Guerrero|battle]] between the Villistas and the expedition occurred on March 29, 1916, at the town of [[Vicente Guerrero|Guerrero]]. After a long march through the [[Sierra Madre]], [[Colonel]] [[George A. Dodd]] and his command of 370 men from the [[7th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|7th Cavalry]] |

||

Colonel Dodd and the 7th Cavalry fought another engagement on April 22 with about 200 Villistas, under Candelaro Cervantes, at small village of Tomochic. As the Americans entered the village, fighting broke out when the Mexicans opened fire from the surrounding hills. Dodd first sent patrols out to engage the Villistas' [[rear guard]], to the east of Tomochic, and after they were "''scattered''" the main body was located on a plain, to the north of town, and brought into action. Skirmishing continued for some time but when it became night the Villistas retreated and the Americans assembled in Tomochic. The 7th Cavalry lost two men killed and four wounded. Colonel Dodd reported that his men killed at least thirty rebels.<ref>http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~wmayo/individual/military/mexicanexpedition.htm</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | On April 12, 1916, about 100 men of the 13th Cavalry were [[Battle of Parral|attacked]] by an estimated 500 Mexican troops as they were leaving the town of [[Parral, Chihuahua|Parral]]. The American commander, Colonel [[Frank Tompkins]], knew he could not win a conventional engagement, so |

||

The next battle was fought at a ranch near Ojos Azules on May 5. In another charge, six troops of the [[11th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|11th Cavalry]] and a detachment of [[Apache Scouts]] routed Julio Acosta and his band of about 100 rebels during what [[Friedrich Katz]] called the "''greatest victory that the Punitive Expedition would achieve.''" Without a single casualty, the Americans killed forty-one Villistas and wounded many more. The survivors, including Acosta, were dispersed but they later regrouped to continue fighting the Carrancistas.<ref>http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/cavalry-lasts.htm</ref><ref>Katz, pg. 575</ref><ref>http://huachuca-www.army.mil/sites/History/PDFS/buffsoldv1.pdf</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | [[United States National Guard|National Guard]] units from [[Texas]], [[Arizona]], and New Mexico |

||

While the 11th Cavalry was engaged at Ojos Azules, dozens of Mexican raiders, under the command of a Villista officer, [[Glenn Springs Raid|attacked]] the towns of [[Boquillas, Texas|Boquillas]] and [[Glenn Springs, Texas|Glenn Springs]], Texas. At Glenn Springs the Mexicans won a small battle against a squad of nine [[14th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|14th Cavalry]] soldiers and at Boquillas the robbed the place and took two captives. When the United States Army learned of the incident a "''little punitive expedition''" was sent into [[Coahuila]] to return the captives and stolen property. On May 12, Colonel George T. Langhorne and two troops from the [[8th Cavalry Regiment|8th Cavalry]] rescued the two prisoners at El Pino without a fight and on May 15 a small detachment of cavalrymen encountered some of the raiders at Castillon. During the "''brief firefight''" that ensued, five of the Mexicans were killed and two were wounded while the Americans had no casualties.<ref>http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jcgdu</ref><ref>Beede, pg. 203-204</ref><ref>http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10914FF3B5512738FDDA10994DD405B868DF1D3</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | Nonetheless, activities on the border were far from dull. The troops had to be on constant alert as border raids were still an occasional nuisance. |

||

On May 14, [[Lieutenant]] [[George S. Patton]], 8th Cavalry, raided the San Miguelito Ranch, near Rubio, Chihuahua. Patton, a future [[World War II]] general, was out looking to buy some corn from the Mexicans when he came across the ranch of [[Julio Cárdenas]], an important leader in the Villista military organization. With fifteen men and three [[Dodge]] [[Armored car (military)|armored cars]], Patton led America's first [[armored vehicle]] attack and personally shot Cardenas and two other men. The young lieutenant then had the three Mexicans strapped to the hood of the cars and driven back to General Pershing's headquarters at [[Colonia Dublan]]. Patton is said to have carved three notches into the twin [[Colt Single Action Army handgun|Colt Peacemaker]]s he carried, representing the men he killed that day. General Pershing called him the "''Bandito''".<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9E03E3DB1031E733A05750C2A9639C946796D6CF Cardena's Family Saw Him Die at Bay; Shot Four Times, Villa Captain Fought Before Mother, Wife, and Daughter], [[New York Times]], May 23, 1916 at 5.</ref> |

|||

In June, [[Lieutenant]] [[George S. Patton]] raided a small community and killed [[Julio Cárdenas]], an important leader in the Villista military organization, and two other men. Patton personally killed Cardenas, and is reported to have carved notches into his revolvers.<ref>[http://www.pattonhq.com/timeline.html Patton Headquarters website timeline]</ref> |

|||

<ref>[http://www.pattonhq.com/timeline.html Patton Headquarters website timeline]</ref><ref>http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars1900s/p/mexican-punitive-expedition.htm</ref><ref>http://www.hsgng.org/pages/pancho.htm</ref> |

|||

The Villistas launched an attack of their own on May 25. This time a small force of ten men from the 7th Cavalry were out looking for stray [[cattle]] and correcting maps when they were ambushed by twenty rebels just south of Cruces. One American [[corporal]] was killed and two other men were wounded though they killed two of the "''bandit leaders''" and drove the rest off.<ref>Pierce pg. 87</ref><ref>http://www.patton-mania.com/George_S_Patton/george_s_patton.html</ref> |

|||

On June 21,<ref>Hurst, James W. ''Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing'' Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2008. ISBN 0313350043</ref> American forces, including elements of the 7th Cavalry and the African-American [[10th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|10th Cavalry Regiment]], attacked [[Mexican Army]] troops in the [[Battle of Carrizal]], resulting in many cavalry troops becoming prisoners of the Mexicans, and effectively ending the 10th Cavalry's usefulness in the campaign.<ref name=usacmh>[http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/mexex.html "Named Campaigns - Mexican Expedition"] [[United States Army Center of Military History]]</ref> |

|||

On June 2, Lieutenant James A. Shannon and twenty Apache scouts fought a small skirmish with some of Candelaro Cervantes' men after they stole a few horses from the [[5th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|5th Cavalry]]. Shannon and the Apaches found the rebels' trail, which was a week old by then, and followed it for some time until finally catching up with the Mexicans near Las Varas Pass, about forty miles south of [[Namiquipa]]. Using the cover of darkness, Sannon and his scouts attacked the Villistas hideout, killing one of them and wounding another without losses to themselves. The one rebel who died was thought to be the the leader as he carried a sword during the fight.<ref>http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FA0A11FF3E5D1A728DDDAD0894DE405B868DF1D3</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | While the expedition did make contact with Villista formations, killing two of his generals and about |

||

Another skirmish was fought on June 9, north of Pershing's headquarters and the city of Chihuahua. Twenty men from the 13th Cavalry encountered an equally small force of Villistas and chased them through Santa Clara Canyon. Three of the Mexicans were killed and the rest escaped. There were no American casualties.<ref>Pierce, pg. 87</ref> |

|||

==Withdrawal== |

|||

| ⚫ | The bulk of American forces were withdrawn in January 1917. Pershing publicly claimed the expedition was a success, although he complained privately to his family that President Wilson had imposed too many restrictions, which made it impossible for him to fulfill his mission.<ref>http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars1900s/p/mexican-punitive-expedition.htm</ref> He admitted to having been "''outwitted and out-bluffed at every turn''" and wrote that "''when the true history is written, it will not be a very inspiring chapter for school children, or even grownups to contemplate. Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw, we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover, like a whipped curr with its tail between its legs.''" |

||

The last engagement of the Mexican Expedition was fought on June 21 when American forces, including elements of the 7th Cavalry and the African-American [[10th Cavalry Regiment (United States)|10th Cavalry]], were defeated by Carrancista soldiers at the [[Battle of Carrizal]]. [[Captain (land)|Captain]] Charles T. Boyd was killed and ten of his men were killed while another twenty-four were taken prisoner. The Mexicans didn't do much better though. They reported the loss of twenty-four men killed and forty-three wounded, including thier commander, General Felix Gomez. When General Pershing learned of the battle he was furious and asked for permission to attack the Carrancista garrison of Chihuahua. President Wilson refused, knowing that it would certainly start a war.<ref>Hurst, James W. ''Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing'' Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2008. ISBN 0313350043</ref><ref>http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/mexex.html</ref><ref>Pierce, pg. 87-88</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | While the expedition did make contact with Villista formations, killing two of his generals and about 160 of his men, it failed in its major objectives, neither stopping border raids — which continued while the expedition was in Mexico, nor capturing Villa. However, between the date of the American withdrawal and Villa's retirement in 1920, Villa's troops were no longer an effective fighting force, being hemmed in by American and Mexican federal troops and money and arms blockades on both sides of the border. |

||

===National Guard service=== |

|||

| ⚫ | [[United States National Guard|National Guard]] units from [[Texas]], [[Arizona]], and New Mexico were called into service on May 8, 1916.<ref name="archives.gov">Prologue Magazine, Winter 1997, Vol. 29, No. 4, The United States Armed Forces and the Mexican Punitive Expedition: Part 2 By Mitchell Yockelson, Retrieved 24 Feb 10, http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/winter/mexican-punitive-expedition-2.html#F8#F8</ref> With congressional approval of the [[National Defense Act]] on June 3, 1916, Guard units from the remainder of the states, and the District of Columbia, were also called for duty on the border.<ref>War Department, Annual Report of the Secretary of War for the Fiscal Year, 1916, Vol. 1 (1916)</ref> In mid-June, President Wilson called out 110,000 National Guard for border service but only one regiment of the National Guard, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, served in Mexico with Pershing's Expedition.<ref>{{cite book|title= Historical & Pictoral Review National Guard of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts|year=1939| publisher=Army and Navy Press|location=Baton Rouge}}</ref> The bulk of of the National Guard troops would cross the border into Mexico but were used instead as a show of force. They spent most of their time training. |

||

| ⚫ | Nonetheless, activities on the border were far from dull. The troops had to be on constant alert as border raids were still an occasional nuisance. The Mexican Expedition proved to be an excellent training environment for the officers and men of the National Guard, who would be recalled to Federal Service later that same year of 1917 for duty in [[World War I]]. Many National Guard leaders in both World Wars traced their first federal service to the Mexican Expedition. |

||

==Aftermath== |

|||

| ⚫ | The bulk of American forces were withdrawn in January 1917. Pershing publicly claimed the expedition was a success, although he complained privately to his family that President Wilson had imposed too many restrictions, which made it impossible for him to fulfill his mission.<ref>http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars1900s/p/mexican-punitive-expedition.htm</ref> He admitted to having been "''outwitted and out-bluffed at every turn''" and wrote that "''when the true history is written, it will not be a very inspiring chapter for school children, or even grownups to contemplate. Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw, we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover, like a whipped curr with its tail between its legs.''" |

||

General Pershing was permitted to bring into New Mexico 527 Chinese refugees who had assisted him during the expedition, despite the ban on Chinese immigration at that time due to the [[Chinese Exclusion Act]]. The Chinese refugees, known as "Pershing's Chinese", were allowed to remain in the U.S. if they worked under the supervision of the military as cooks and servants on bases. In 1921, Congress passed Public Resolution 29, which allowed them to remain in the country permanently under the conditions of the 1892 [[Geary Act]]. Most of them settled in [[San Antonio]].<ref>[http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/CC/pjc1.html Chinese in Texas]</ref> |

General Pershing was permitted to bring into New Mexico 527 Chinese refugees who had assisted him during the expedition, despite the ban on Chinese immigration at that time due to the [[Chinese Exclusion Act]]. The Chinese refugees, known as "Pershing's Chinese", were allowed to remain in the U.S. if they worked under the supervision of the military as cooks and servants on bases. In 1921, Congress passed Public Resolution 29, which allowed them to remain in the country permanently under the conditions of the 1892 [[Geary Act]]. Most of them settled in [[San Antonio]].<ref>[http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/CC/pjc1.html Chinese in Texas]</ref> |

||

| Line 105: | Line 117: | ||

*{{cite book|last=Boot|first=Max|coauthors=|title=The savage wars of peace: small wars and the rise of American power|series=|url=|year=2003|location=|publisher=Basic Books|isbn=046500721X}} |

*{{cite book|last=Boot|first=Max|coauthors=|title=The savage wars of peace: small wars and the rise of American power|series=|url=|year=2003|location=|publisher=Basic Books|isbn=046500721X}} |

||

*{{cite book|last=Beede|first=Benjamin R.|coauthors=|title=The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898-1934: an encyclopedia|series=|url=|year=1994|location=|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn= 0824056248}} |

*{{cite book|last=Beede|first=Benjamin R.|coauthors=|title=The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898-1934: an encyclopedia|series=|url=|year=1994|location=|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn= 0824056248}} |

||

*{{cite book|last=Pierce|first=Frank C.|authorlink=|title=A brief history of the lower Rio Grande valley|publisher=George Banta publishing company|series=|year=1917|doi=|isbn=}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Katz|first=Friedrich|authorlink=|title=The life and times of Pancho Villa|publisher=Stanford University Press|series=|year=1998|doi=|isbn=0804730466}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category}} |

{{Commons category}} |

||

Revision as of 08:11, 24 November 2011

| Pancho Villa Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican Revolution, Border War | |||||||

Cartoon by Clifford Berryman reflects American attitudes about the expedition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Villistas Carrancistas | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Pancho Villa Felipe Angeles Julio Cárdenas | ||||||

The Pancho Villa Expedition—officially known in the United States as the Mexican Expedition[1] and sometimes colloquially referred to as the Punitive Expedition—was a military operation conducted by the United States Army against the paramilitary forces of Mexican insurgent Francisco "Pancho" Villa from 1916 to 1917 during the Mexican Revolution. The expedition was launched in retaliation for Villa's attack on the town of Columbus, New Mexico and was the most remembered event of the Border War. The expeditions had one objective, to capture Villa dead or alive and put a stop to any future forays by his paramilitary forces on American soil.[2] The official beginning and ending dates of the Mexican Expedition are March 14, 1916 and February 7, 1917.

Background

Trouble between the United States and Pancho Villa had been growing since 1915, when the United States government disappointed Villa by siding with and giving its official recognition to Venustiano Carranza's national government. Feeling betrayed, Villa began attacking American property and citizens in northern Mexico. The most serious incident occurred in January 1916, when sixteen American employees of the ASARCO company were removed from a train near Santa Isabel, Chihuahua and summarily stripped and executed. Villa kept his men south of the border to avoid a direct confrontation with the United States Army forces which were being deployed to protect the border.

At approximately 4:17 am on March 9, 1916, Villa's troops attacked Columbus, New Mexico and its local detachment of the 13th Cavalry Regiment, killing 10 civilians and eight soldiers, and wounding two civilians and six soldiers.[3][4] The raiders also burned the town, took many horses and mules and seized available machine guns, ammunition and merchandise, before being pursued back into Mexico. However, Villa's troops suffered considerable losses, with at least 67 dead. About 13 others would later die of their wounds. Five Mexicans were taken prisoner and later executed. The battle may have been spurred by an American merchant in Columbus who supplied Villa with weapons and ammunition. After Villa paid several thousand dollars in cash in advance, the merchant decided to stop supplying him with weapons and demanded payment in gold.[citation needed]

Expedition

On March 15,[5] on orders from President Woodrow Wilson, Major General John J. Pershing led an expeditionary force of 4,800 men into Mexico to capture Villa, who had already had more than a week to disperse and conceal his forces before the expedition tried to seek them out in unmapped terrain. Beginning March 19, the newly-adopted Curtiss JN-4 airplane was used by the 1st Provisional Aero Squadron to conduct aerial reconnaissance.[6] Pershing divided his force into two "flying columns" to seek out Villa, and made his main base encampment at Casas Grandes, Chihuahua. Due to disputes with the Carranza administration over the use of the Mexico North Western Railway to supply his troops, the United States Army employed a truck-train system to convoy supplies to the encampment and the Signal Corps set up wireless telegraph service from the border to Pershing's headquarters.

The first battle between the Villistas and the expedition occurred on March 29, 1916, at San Geronimo Ranch, near the town of Guerrero. After a long march through the Sierra Madre, Colonel George A. Dodd and his command of 370 men, from the 7th Cavalry, launched what was called the "last true cavalry charge" in history. During the five hour battle, Pancho Villa lost over seventy-five of his men killed or wounded and he was forced to retreat into the mountains. Only five of the Americans were hurt, none of them fatally. The battle is considered the single most successful engagement of the expedition and it was the closest Pershing's men came to capturing Villa.[7][8][9][10][11]

On April 12, 1916, about 100 men of the 13th Cavalry were attacked by an estimated 500 Mexican troops as they were leaving the town of Parral. The American commander, Colonel Frank Tompkins, knew he could not win a conventional engagement, so in a running battle he and his men were able to retreat to a fortified village nearby while repulsing Mexican cavalry charges at the same time. Two Americans were killed in the fight and another six were wounded, the Mexicans lost between fourteen and seventy men according to conflicting accounts.[12][13]

Colonel Dodd and the 7th Cavalry fought another engagement on April 22 with about 200 Villistas, under Candelaro Cervantes, at small village of Tomochic. As the Americans entered the village, fighting broke out when the Mexicans opened fire from the surrounding hills. Dodd first sent patrols out to engage the Villistas' rear guard, to the east of Tomochic, and after they were "scattered" the main body was located on a plain, to the north of town, and brought into action. Skirmishing continued for some time but when it became night the Villistas retreated and the Americans assembled in Tomochic. The 7th Cavalry lost two men killed and four wounded. Colonel Dodd reported that his men killed at least thirty rebels.[14]

The next battle was fought at a ranch near Ojos Azules on May 5. In another charge, six troops of the 11th Cavalry and a detachment of Apache Scouts routed Julio Acosta and his band of about 100 rebels during what Friedrich Katz called the "greatest victory that the Punitive Expedition would achieve." Without a single casualty, the Americans killed forty-one Villistas and wounded many more. The survivors, including Acosta, were dispersed but they later regrouped to continue fighting the Carrancistas.[15][16][17]

While the 11th Cavalry was engaged at Ojos Azules, dozens of Mexican raiders, under the command of a Villista officer, attacked the towns of Boquillas and Glenn Springs, Texas. At Glenn Springs the Mexicans won a small battle against a squad of nine 14th Cavalry soldiers and at Boquillas the robbed the place and took two captives. When the United States Army learned of the incident a "little punitive expedition" was sent into Coahuila to return the captives and stolen property. On May 12, Colonel George T. Langhorne and two troops from the 8th Cavalry rescued the two prisoners at El Pino without a fight and on May 15 a small detachment of cavalrymen encountered some of the raiders at Castillon. During the "brief firefight" that ensued, five of the Mexicans were killed and two were wounded while the Americans had no casualties.[18][19][20]

On May 14, Lieutenant George S. Patton, 8th Cavalry, raided the San Miguelito Ranch, near Rubio, Chihuahua. Patton, a future World War II general, was out looking to buy some corn from the Mexicans when he came across the ranch of Julio Cárdenas, an important leader in the Villista military organization. With fifteen men and three Dodge armored cars, Patton led America's first armored vehicle attack and personally shot Cardenas and two other men. The young lieutenant then had the three Mexicans strapped to the hood of the cars and driven back to General Pershing's headquarters at Colonia Dublan. Patton is said to have carved three notches into the twin Colt Peacemakers he carried, representing the men he killed that day. General Pershing called him the "Bandito".[21] [22][23][24]

The Villistas launched an attack of their own on May 25. This time a small force of ten men from the 7th Cavalry were out looking for stray cattle and correcting maps when they were ambushed by twenty rebels just south of Cruces. One American corporal was killed and two other men were wounded though they killed two of the "bandit leaders" and drove the rest off.[25][26]

On June 2, Lieutenant James A. Shannon and twenty Apache scouts fought a small skirmish with some of Candelaro Cervantes' men after they stole a few horses from the 5th Cavalry. Shannon and the Apaches found the rebels' trail, which was a week old by then, and followed it for some time until finally catching up with the Mexicans near Las Varas Pass, about forty miles south of Namiquipa. Using the cover of darkness, Sannon and his scouts attacked the Villistas hideout, killing one of them and wounding another without losses to themselves. The one rebel who died was thought to be the the leader as he carried a sword during the fight.[27]

Another skirmish was fought on June 9, north of Pershing's headquarters and the city of Chihuahua. Twenty men from the 13th Cavalry encountered an equally small force of Villistas and chased them through Santa Clara Canyon. Three of the Mexicans were killed and the rest escaped. There were no American casualties.[28]

The last engagement of the Mexican Expedition was fought on June 21 when American forces, including elements of the 7th Cavalry and the African-American 10th Cavalry, were defeated by Carrancista soldiers at the Battle of Carrizal. Captain Charles T. Boyd was killed and ten of his men were killed while another twenty-four were taken prisoner. The Mexicans didn't do much better though. They reported the loss of twenty-four men killed and forty-three wounded, including thier commander, General Felix Gomez. When General Pershing learned of the battle he was furious and asked for permission to attack the Carrancista garrison of Chihuahua. President Wilson refused, knowing that it would certainly start a war.[29][30][31]

While the expedition did make contact with Villista formations, killing two of his generals and about 160 of his men, it failed in its major objectives, neither stopping border raids — which continued while the expedition was in Mexico, nor capturing Villa. However, between the date of the American withdrawal and Villa's retirement in 1920, Villa's troops were no longer an effective fighting force, being hemmed in by American and Mexican federal troops and money and arms blockades on both sides of the border.

National Guard service

National Guard units from Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico were called into service on May 8, 1916.[32] With congressional approval of the National Defense Act on June 3, 1916, Guard units from the remainder of the states, and the District of Columbia, were also called for duty on the border.[33] In mid-June, President Wilson called out 110,000 National Guard for border service but only one regiment of the National Guard, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, served in Mexico with Pershing's Expedition.[34] The bulk of of the National Guard troops would cross the border into Mexico but were used instead as a show of force. They spent most of their time training.

Nonetheless, activities on the border were far from dull. The troops had to be on constant alert as border raids were still an occasional nuisance. The Mexican Expedition proved to be an excellent training environment for the officers and men of the National Guard, who would be recalled to Federal Service later that same year of 1917 for duty in World War I. Many National Guard leaders in both World Wars traced their first federal service to the Mexican Expedition.

Aftermath

The bulk of American forces were withdrawn in January 1917. Pershing publicly claimed the expedition was a success, although he complained privately to his family that President Wilson had imposed too many restrictions, which made it impossible for him to fulfill his mission.[35] He admitted to having been "outwitted and out-bluffed at every turn" and wrote that "when the true history is written, it will not be a very inspiring chapter for school children, or even grownups to contemplate. Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw, we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover, like a whipped curr with its tail between its legs."

General Pershing was permitted to bring into New Mexico 527 Chinese refugees who had assisted him during the expedition, despite the ban on Chinese immigration at that time due to the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Chinese refugees, known as "Pershing's Chinese", were allowed to remain in the U.S. if they worked under the supervision of the military as cooks and servants on bases. In 1921, Congress passed Public Resolution 29, which allowed them to remain in the country permanently under the conditions of the 1892 Geary Act. Most of them settled in San Antonio.[36]

Soldiers who took part in the Villa campaign were awarded the Mexican Service Medal.

Order of Battle

United States Army:

Gallery

-

Columbus, New Mexico after Pancho Villa's attack on March 9, 1916

-

Men of the 13th Cavalry wait to embark a train at Columbus for operations in the Pancho Villa Expedition

-

Staging area in Columbus, New Mexico for truck trains that supplied John J. Pershing's troops during the expedition

-

Company A, First Arkansas Infantry, on the skirmish line near Deming, New Mexico during the 1916 Mexican Expedition

-

The 1st Aero Squadron on the Mexican border in 1916, marked with red star insignia on rudder and wings

-

Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry who were taken prisoner during the Battle of Carrizal on June 21, 1916

-

Members of the 6th and 16th Infantry withdrawing homeward in January 1917

See also

References

Notes

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/mexex.html

- ^ http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/fall/mexican-punitive-expedition-1.html

- ^ "Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca: Villa's Raid on Columbus, New Mexico". Huachuca Illustrated. 1. 1993. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (1916). "The March Of Events: Making Mexico Understand". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXI: 584–593. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hal Marcovitz (March 2002). Pancho Villa. Infobase Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9780791072578. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ James W. Hurst (2008). Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing: the Punitive Expedition in Mexico. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 122. ISBN 9780313350047. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/2-7cav.htm

- ^ Boot, pg. 199

- ^ Beede, pg. 218-219

- ^ Boot, pg. 199

- ^ http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/mexico_pershing.htm

- ^ Boot, pg. 201-203

- ^ http://www.cabq.gov/veterans/history/worldwari

- ^ http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~wmayo/individual/military/mexicanexpedition.htm

- ^ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/cavalry-lasts.htm

- ^ Katz, pg. 575

- ^ http://huachuca-www.army.mil/sites/History/PDFS/buffsoldv1.pdf

- ^ http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jcgdu

- ^ Beede, pg. 203-204

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10914FF3B5512738FDDA10994DD405B868DF1D3

- ^ Cardena's Family Saw Him Die at Bay; Shot Four Times, Villa Captain Fought Before Mother, Wife, and Daughter, New York Times, May 23, 1916 at 5.

- ^ Patton Headquarters website timeline

- ^ http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars1900s/p/mexican-punitive-expedition.htm

- ^ http://www.hsgng.org/pages/pancho.htm

- ^ Pierce pg. 87

- ^ http://www.patton-mania.com/George_S_Patton/george_s_patton.html

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FA0A11FF3E5D1A728DDDAD0894DE405B868DF1D3

- ^ Pierce, pg. 87

- ^ Hurst, James W. Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2008. ISBN 0313350043

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/mexex.html

- ^ Pierce, pg. 87-88

- ^ Prologue Magazine, Winter 1997, Vol. 29, No. 4, The United States Armed Forces and the Mexican Punitive Expedition: Part 2 By Mitchell Yockelson, Retrieved 24 Feb 10, http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/winter/mexican-punitive-expedition-2.html#F8#F8

- ^ War Department, Annual Report of the Secretary of War for the Fiscal Year, 1916, Vol. 1 (1916)

- ^ Historical & Pictoral Review National Guard of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Baton Rouge: Army and Navy Press. 1939.

- ^ http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars1900s/p/mexican-punitive-expedition.htm

- ^ Chinese in Texas

Bibliography

- Boot, Max (2003). The savage wars of peace: small wars and the rise of American power. Basic Books. ISBN 046500721X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Beede, Benjamin R. (1994). The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898-1934: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0824056248.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Pierce, Frank C. (1917). A brief history of the lower Rio Grande valley. George Banta publishing company.

- Katz, Friedrich (1998). The life and times of Pancho Villa. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804730466.