Akan people: Difference between revisions

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

===Patrilineality=== |

===Patrilineality=== |

||

Other aspects of the Akan culture were determined [[patrilineally]], rather than matrilineally. Thus their culture was ''both'' matrilineal and patrilineal, or [[ambilineal]]. There were 12 patrilineal ''[[ntoro]]'' (which means life force, or spirit) groups, and each person was a lifelong member of one's father's group. Each ''ntoro'' had its own surnames, taboos, ritual purifications and forms of etiquette – its own part of the Akan culture.<ref name=encyBr /> |

Other aspects of the Akan culture were determined [[patrilineally]], rather than matrilineally. Thus their culture was ''both'' matrilineal and patrilineal, or [[ambilineal]]. There were 12 patrilineal ''[[ntoro]]'' (which means life force, or spirit) groups, and each person was a lifelong member of one's father's group. Each ''ntoro'' had its own surnames, taboos, ritual purifications and forms of etiquette – its own part of the Akan culture.<ref name=encyBr /> |

||

==Elements of Akan culture== |

|||

[[File:Kent wove.jpg||thumb|left| Kente cloth]] |

|||

*[[Adinkra]] |

|||

*[[Akan goldweights]] |

|||

*[[Akan name]]s |

|||

*[[Akan Chieftaincy]] |

|||

*[[Akan Calendar]] |

|||

*[[Akan religion]] |

|||

*[[Akan art]] |

|||

*[[Abusua]] |

|||

*[[Adamorobe Sign Language]] |

|||

*[[Bono state]] |

|||

*[[Kente]] |

|||

*[[Sankofa]] |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 10:50, 15 February 2011

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| ~12 Million | |

| ~8 Million | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| ~41,000 | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| unknown | |

| Other Caribbean countries | unknown |

| Languages | |

| Central Tano languages, English, French | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, African traditional religion, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Akan | |

The Akan people are an ethnic linguistic group of West Africa. They speak the Akan languages.

This group includes the following sub-ethnic groups: Ashanti, the Akwamu, the Akyem , the Akuapem, the Denkyira, the Abron, the Aowin, the Ahanta, the Anyi, the Akropong-Akuapem, the Baoule, the Chokosi, the Coromantins, the Fante, the Kwahu, the Guan people, the Sefwi, the Ahafo, the Assin, the Evalue, the Wassa the Adjukru, the Akye, the Alladian, the Attie,the M'Bato, the Abidji, the Bri-an, the Avikam,the Avatime the Ebrie, the Ehotile, the Nzema, the Ndyuka people and other peoples of both modern day Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire or, origin in these countries. The Akan also belong to several clans called Abusua which transcend these sub-ethnic groups.

Origin

Akans trace their ancestry to Bono Manso which existed in the middle ages.

Brief history

From the 15th century to the 19th century, the Akan people dominated gold mining and the gold trade in the region. From the 17th century on, the Akan were among the most powerful group(s) in the West African region. They fought many battles against the European colonists to maintain autonomy. During the slave trade, enslaved Akans such as the Coromantins of Jamaica, and numerous others including the descendants of the Akwamu in St. John were responsible for numerous of slave rebellions in the new world.

By the early 1900s, all Akan lands were colonized by the French and English. On the 6th of March 1957, Akan lands in the Gold Coast rejected British rule, by the efforts of Kwame Nkrumah, and were joined with British Togoland to form the independent nation of Ghana. The Ivory Coast became independent on 7 August 1960.

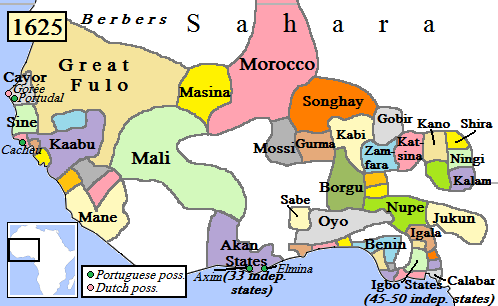

1625 historical map of west Africa

Culture

Akan art is wide-ranging and renowned, especially for the tradition of crafting bronze gold weights, which were made using the lost wax casting method. Branches of the Akan include the Abron and the Afutu. The Akan culture is the most dominant and apparent in present-day Ghana.

Some of their most important mythological stories are called anansesem. Anansesem literally means 'the spider story', but can in a figurative sense also mean "traveler's tales". These "spider stories" are sometimes also referred to as nyankomsem; 'words of a sky god'. The stories generally, but not always, revolve around Kwaku Ananse, a trickster spirit, often depicted as a spider, human, or a combination thereof.

Matrilineality

The Akan rural and political organization was based on matrilineal lineages, which were the basis of inheritance and succession. A lineage was defined as all those related by matrilineal descent from a particular ancestress. Several lineages would be grouped into a political unit headed by a chief and a council of elders, each of whom was the elected head of a lineage. Public offices were thus vested in the lineage, as was land tenure and other lineage property. In other words, lineage property had to be inherited only by matrilineal kin.[1]

The political units above were likewise grouped into eight larger groups called abusua, similar to clans in other societies: Aduana, Agona, Asakyiri, Asenie, Asona, Bretuo, Ekuona and Oyoko; or sometimes more than these. The members of each abusua were united by their belief that they were all descended from the same ancient ancestress, so marriage between members of the same abusua was forbidden. One inherited or was a lifelong member of the lineage, the political unit and the abusua of one's mother, regardless of one's gender and/or marriage.[1]

According to this source[2] of further information about the Akan, "A man is strongly related to his mother's brother (wɔfa) but only weakly related to his father's brother. This must be viewed in the context of a polygamous society in which the mother/child bond is likely to be much stronger than the father/child bond. As a result, in inheritance, a man's nephew (his sister's son) (wɔfase) will have priority over his own son. Uncle-nephew relationships therefore assume a dominant position."[2]

"The principles governing inheritance stress sex, generation and age – that is to say, men come before women and seniors before juniors." .... When a woman’s brothers were available, a consideration of generational seniority stipulated that the line of brothers be exhausted before the right to inherit lineage property passed down to the next senior genealogical generation of sisters' sons. Finally, "it is when all possible male heirs have been exhausted that the females" may inherit.[2]

Patrilineality

Other aspects of the Akan culture were determined patrilineally, rather than matrilineally. Thus their culture was both matrilineal and patrilineal, or ambilineal. There were 12 patrilineal ntoro (which means life force, or spirit) groups, and each person was a lifelong member of one's father's group. Each ntoro had its own surnames, taboos, ritual purifications and forms of etiquette – its own part of the Akan culture.[1]

See also

- Empire of Ashanti

- Gyaaman

- Bono Manso

- Rulers of the Akan state of Asante

- List of rulers of the Akan state of Adanse

- Rulers of the Akan state of Akyem Abuakwa

- List of rulers of the Akan states of Akwamu and Twifo-Heman

- List of rulers of the Akan state of Denkyira

- List of rulers of the Akan state of Bono-Tekyiman

- List of rulers of the Akan state of Gyaaman

Endnotes

- ^ a b c Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 1970. William Benton, publisher (The University of Chicago). ISBN 0-85229-135-3, Vol. 1, p.477. (This p. 477 Akan article was written by Kofi Abrefa Busia, formerly Professor of Sociology and Culture of Africa at the University of Leiden, Netherlands.)

- ^ a b c http://ashanti.com.au/pb/wp_8078438f.html

References

- Antubam, Kofi; Ghana's heritage of Culture, Leipzig 1963

- Kyerematen, A.A.Y.; Panoply of Ghana, London 1964

- Meyerowitz, Eva L. R.; Akan Traditions of Origin, London (published around 1950)

- Meyerowitz, Eva L. R.; At the court of an African King, London 1962

- Obeng, Ernest E.; Ancient Ashanti Chieftaincy, Tema (Ghana) 1986

- Bartle, Philip F.W. (January 1978). "Forty Days; The AkanCalendar". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute.. (Edinburgh University Press) 48 (1): 80–84.

- For the Akan, the first-born twin is considered the younger, as the elder stays behind to help the younger out.

- Kente Cloth." African Journey. webmaster@projectexploration.org. 25 Sep 2007.

- Effah-Gyamfi, Kwaku (1979) Traditional history of the Bono State Legon: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana.

- Effah-Gyamfi, Kwaku (1985) Bono Manso: an archaeological investigation into early Akan urbanism (African occasional papers, no. 2) Calgary: Dept. of Archaeology, University of Calgary Press. ISBN 0-919813-27-5

- Meyerowitz, E.L.R. (1949) 'Bono-Mansu, the earliest centre of civilisation in the Gold Coast', Proceedings of the III International West African Conference, 118–120.