Palestinian refugees: Difference between revisions

Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) m →Origin of the Palestinian refugees: minor reword |

Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) →Origin of the Palestinian refugees: expand on background |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

[[Image:Palestinian refugees.jpg|300px|thumb|right|[[1948 Palestinian exodus|Palestinian refugees in 1948]]]] |

[[Image:Palestinian refugees.jpg|300px|thumb|right|[[1948 Palestinian exodus|Palestinian refugees in 1948]]]] |

||

{{main article|1948 Palestinian exodus|Causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus|Palestinian Exodus 1949 to 1956}} |

{{main article|1948 Palestinian exodus|Causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus|Palestinian Exodus 1949 to 1956}} |

||

The hostilities of the [[1948 Arab–Israeli War]] erupted in mid-May 1948, involving the newly established State of Israel and the four neighbouring Arab states. The fighting took place throughout the territory of the British Mandate. The fighting resulted in the flight of peoples (both Jews and Arabs) from their homes. |

|||

Between December 1947 and March 1948, around 100,000 Palestinians left their homes. Among them were many from the higher and middle classes from the cities, who left voluntarily, expecting to return when the situation had calmed down.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], pp.138-139.</ref> From April to July, between 250,000 and 300,000 fled in front of Haganah offensives, mainly from the towns of [[Operation Bi'ur Hametz|Haifa]], Tiberias, Beit-Shean, Safed, Jaffa and Acre, that lost more than 90 percent of their Arab inhabitants.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], p.262</ref> Some expulsions arose, particularly along the Tel-Aviv - Jerusalem road<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], pp.233-240.</ref> and in Eastern Galilee.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], pp.248-252.</ref> After the truce of June, about 100,000 Palestinians became refugees.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], p.448.</ref> |

Between December 1947 and March 1948, around 100,000 Palestinians left their homes. Among them were many from the higher and middle classes from the cities, who left voluntarily, expecting to return when the situation had calmed down.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], pp.138-139.</ref> From April to July, between 250,000 and 300,000 fled in front of Haganah offensives, mainly from the towns of [[Operation Bi'ur Hametz|Haifa]], Tiberias, Beit-Shean, Safed, Jaffa and Acre, that lost more than 90 percent of their Arab inhabitants.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], p.262</ref> Some expulsions arose, particularly along the Tel-Aviv - Jerusalem road<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], pp.233-240.</ref> and in Eastern Galilee.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], pp.248-252.</ref> After the truce of June, about 100,000 Palestinians became refugees.<ref>[[#morris birth revisited|Benny Morris (2003)]], p.448.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:55, 14 May 2009

| Total 2005 population (including descendants): | 4.25 million [1] |

|---|---|

| Estimated original 1948-49 refugees: | 367,000 to 950,000 |

| Regions with significant populations: | Gaza Strip, Jordan, West Bank, Lebanon, Syria |

| Languages: | Arabic |

| Religions: | Sunni Islam, Greek Orthodoxy, Greek Catholicism, other forms of Christianity |

Palestinian refugees or Palestine refugees are people or their descendants, predominantly Arabs, who fled or were expelled from their homes during and after the 1948 Palestine War, within that part of the British Mandate of Palestine that the United Nations decided should be the territory of the State of Israel.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) defines a Palestinian refugee as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict". UNRWA's definition of a Palestinian refugee also covers the descendants of persons who became refugees in 1948[2] regardless of whether they reside in areas designated as refugee camps or in established, permanent communities.[3] This is a major departure from the normal definition of refugee.

Descendants of Palestinian refugees under the authority of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) are the only group to be granted refugee status on that basis alone.[4] Based on this definition, the number of Palestine refugees has grown from 711,000 in 1950[5] to over four million registered with the UN in 2002.

Some displaced Palestinians resettled in other countries where their situation is often precarious. Many remained refugees and continue to reside in refugee camps.

Origin of the Palestinian refugees

1948 Arab-Israeli War

The examples and perspective in this article may not include all significant viewpoints. (March 2009) |

The hostilities of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War erupted in mid-May 1948, involving the newly established State of Israel and the four neighbouring Arab states. The fighting took place throughout the territory of the British Mandate. The fighting resulted in the flight of peoples (both Jews and Arabs) from their homes.

Between December 1947 and March 1948, around 100,000 Palestinians left their homes. Among them were many from the higher and middle classes from the cities, who left voluntarily, expecting to return when the situation had calmed down.[6] From April to July, between 250,000 and 300,000 fled in front of Haganah offensives, mainly from the towns of Haifa, Tiberias, Beit-Shean, Safed, Jaffa and Acre, that lost more than 90 percent of their Arab inhabitants.[7] Some expulsions arose, particularly along the Tel-Aviv - Jerusalem road[8] and in Eastern Galilee.[9] After the truce of June, about 100,000 Palestinians became refugees.[10]

About 50,000 inhabitants of Lydda and Ramle were expelled towards Ramallah by Israeli forces during Operation Danny,[11] and most others during clearing operations performed by the IDF on its rear areas.[12] During Operation Dekel, the Arabs of Nazareth and South Galilee could remain in their homes.[13] They later formed the core of the Arab Israelis. From October to November 1948, the IDF launched Operation Yoav to chase Egyptian forces from the Negev and Operation Hiram to chase the Arab Liberation Army from North Galilee. This generated an exodus of 200,000 to 220,000 Palestinians. Here, Arabs fled fearing atrocities or were expelled if they had not fled.[14] During Operation Hiram, at least nine massacres of Arabs were performed by IDF soldiers.[15] After the war, from 1948 to 1950, the IDF cleared its borders, which resulted in the expulsion of around 30,000 to 40,000 Arabs.[16]

The causes and responsibilities of the exodus are a matter of controversy among historians and commentators of the conflict.[17]. While contested by many academics such as professor Efraim Karsh,[18] historian Anita Shapira,[19] and author Norman Finkelstein[20] Morris' interpretations have become widely accepted among New Historians, and other academic and public circles. [21]. Whereas historians now agree on most of the events of that period there is still disagreement on whether the exodus was the result of a plan designed before or during the war by Zionist leaders, or whether it was an unintended result of the war.[22]

Six days war

During the Six days war around 280,000 to 325,000 Palestinians flight[23] out of the territories occupied by Israel during and in the aftermath of the Six-Day War including the demolition of the Palestinian villages of Imwas, Yalo, and Beit Nuba, Surit, Beit Awwa, Beit Mirsem, Shuyukh, Jiftlik, Agarith and Huseirat and the "emptying" of the refugee camps of ʿAqabat Jabr and ʿEin Sulṭān.[24] The Special Committee heard allegations of the destruction of over 400 Arab villages, but no evidence in corroboration was furnished to the Special Committee to investigate Israeli practices affecting the human rights of the population of the occupied territories.[25]

UNRWA definition

Whereas most refugees are the concern of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), most Palestinian refugees - those in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan - come under the older body UNRWA. On 11 December 1948, UN Resolution 194 was passed. It called, among other things, for the return of refugees from Arab-Israeli hostilities then ongoing, although it did not specify only Arab refugees. Resolution 302 (IV) of 8 December 1949, set up UNRWA specifically to deal with the Palestinian refugee problem. Palestinian refugees outside of UNRWA's area of operations do fall under UNHCR's mandate, however.

The United Nations never formally defined the term Palestinian refugee. The definition used in practice evolved independently of the UNHCR definition, established by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The UNRWA defines a Palestine refugee as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict,"[26] This definition has generally only been applied to those who living in one of the countries where UNRWA provides relief. The UNRWA also registers as refugees descendants in the male line of Palestine refugees, and persons in need of support who first became refugees as a result of the 1967 conflict. The UNRWA definition in practice is thus both more restrictive and more inclusive than the 1951 definition. For example, the definition excludes persons taking refuge in countries other than Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, but includes descendants of refugees as well as the refugees themselves. In many cases UNHCR provides support for the children of refugees too.

Persons receiving relief support from UNRWA are explicitly excluded from the 1951 Convention, depriving them of some of the benefits of that convention such as some legal protections. However, a 2002 decision of UNHCR made it clear that the 1951 Convention applies at least to Palestinian refugees who need support but fail to fit the UNRWA working definition.[27] UNRWA records show about 5% "False and duplicate registration."[27] Today, about 30% of those registering with the UNRWA as Palestine refugees are living in areas designated as refugee camps.[28]

Critics of UNRWA say that the present definition give Palestine refugees a favored status when compared with other refugee groups, which the UNHCR defines in terms of nationality as opposed to a relatively short number of years of residency.[29] Defenders of UNRWA respond that it is precisely the stateless status of the Palestinians under British mandate in 1948 that made it necessary to create a definition of refugee based on other criteria than nationality. Historians, such as Martha Gellhorn and Dr. Walter Pinner, have also blamed UNRWA for distortion of statistics and even of sheer fraud. Pinner wrote in 1959 that the actual number of refugees then was only 367,000.[30]

Refugee statistics

The number of Palestine refugees seem to vary depending on who is reporting. Both Israel and Palestine sources seem to suggest inflated and deflated numbers. The 1948-49 for example, the Israel government suggested a number as low as 520,000 as opposed to 850,000 by their Palestine counterparts. The UNRWA cites 726,000 people.[31]

The number of descendents of Palestinian refugees by country as of 2005 were as follows:

- Jordan 1,827,877 refugees

- Gaza 986,034 refugees

- West Bank 699,817 refugees

- Syria 432,048 refugees

- Lebanon 404,170 refugees

- Saudi Arabia 240,000 refugees

- Egypt 70,245 refugees[1]

Note: The UNHCR does NOT consider refugee status hereditary. Refugees are required to be granted asylum where they arrive, and their descendents given citizenship.[32]

Jordan refugees

Several commentators of the Palestinian refugee situation have voiced concerns over the population estimates. Former UNRWA chief-attorney James G. Lindsay considers the current number of refugees to be largely inaccurate: "In Jordan, where 2 million Palestinian refugees live, all but 167,000 have citizenship, and are fully eligible for government services including education and health care." Lindsay suggests that eliminating services to refugees whose needs are subsidized by Jordan "would reduce the refugee list by 40%." [33][34]

Positions on the problem and right of return

On 11 December 1948 the General Assembly discussed Bernadotte's report and resolved: "that refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbour should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.[35]" This resolution has been annually re-affirmed by the UN ever since, but some say Israel continues to defy it and prevent the return of the refugees to their homes[citation needed].

The Arab League issued instructions barring the Arab states from granting citizenship to Palestinian Arab refugees (or their descendants) "to avoid dissolution of their identity and protect their right to return to their homeland".[36]

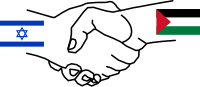

| Part of a series on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict |

| Israeli–Palestinian peace process |

|---|

|

Palestinian leaders claim a right of return for Palestinian refugees. Their claim is based on Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which declares that "Everyone has the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country." Although all Arab League members at the time- Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen- voted against the resolution,[37] they also cite United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, which "Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return [...]."[38] However Resolution 194 refers to traditional (non-hereditary) refugees, not Palestinian refugees.

The Palestinian National Authority supports this claim, and has been prepared to negotiate its implementation at the various peace talks. Both Fatah and Hamas hold a strong position for a right of return, with Fatah being prepared to discuss the issue while Hamas is not.[39]

Since 1967, several attempts have been made to meet the terms of both Israel and the Palestinian people. Most recently, the government of Israel, in collaboration with the United Nations, attempted to accommodate the refugee concern by facilitating the creation of an independent Palestinian state. This was negotiated during the Oslo Accords. However, the Second Intifada and Israeli retaliation has halted the phasing process and makes the likelihood of a future sovereign Palestinian state uncertain. [40][41]

Further reading

- Bowker, Robert P. G. (2003). Palestinian Refugees: Mythology, Identity, and the Search for Peace. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1588262022

- Gelber, Yoav (2006). Palestine 1948. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-075-0.

- Gerson, Allan (1978). Israel, the West Bank and International Law. Routledge. ISBN 0714630918

- McDowall, David (1989). Palestine and Israel: The Uprising and Beyond. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1850432899.

- Morris, Benny (2003). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521009677

- Pappe, Ilan (2006). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, London and New York: Oneworld, 2006. ISBN 1851684670

- Segev, Tom (2007) 1967 Israel, The War and the Year that Transformed the Middle East Little Brown ISBN 978-0-316-72478-4

- Seliktar, Ofira (2002). Divided We Stand: American Jews, Israel, and the Peace Process. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-97408-1

References

- ^ a b "Total registered refugees per country and area" (PDF). United Nations. 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Who is a Palestine refugee?" (HTML). UNRWA. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Ruth Lapidoth (2002). "Legal aspects of the Palestinian refugee question" (HTML). Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Publications/Statistics" (HTML). UNRWA. 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the Period from [[11 December]] [[1949]] to [[23 October]] [[1950]]" (HTML). United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine. 1950. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Benny Morris (2003), pp.138-139.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), p.262

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), pp.233-240.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), pp.248-252.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), p.448.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), pp.423-436.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), p.438.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), pp.415-423.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), p.492.

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims - First Arab-Israeli War - Operation Yoav.

- ^ Benny Morris (2003), p.538

- ^ Shlaim, Avi, "The War of the Israeli Historians." Center for Arab Studies, 1 December 2003 (retrieved 17 February 2009)

- ^ http://www.meforum.org/article/711 Benny Morris's Reign of Error, Revisited

- ^ Anita Shapira, The Past Is Not a Foreign Country, The New Republic, 29 November 1999.

- ^ N. Finkelstein, 1991, ‘Myths, Old and New’, J. Palestine Studies, 21(1), p. 66-89

- ^ Shlaim, Avi. (1995) The Debate about 1948. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 27:3, 287-304.

- ^ Benny Morris, 1989, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, Cambridge University Press; Benny Morris, 1991, 1948 and after; Israel and the Palestinians, Clarendon Press, Oxford; Walid Khalidi, 1992, All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, Institute for Palestine Studies; Nur Masalha, 1992, Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of "Transfer" in Zionist Political Thought, Institue for Palestine Studies; Efraim Karsh, 1997, Fabricating Israeli History: The "New Historians", Cass; Benny Morris, 2004, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press; Yoav Gelber, 2006, Palestine 1948: War, Escape and the Palestinian Refugee Problem, Oxford University Press; Ilan Pappé, 2006, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, OneWorld

- ^ Bowker, 2003, p. 81.

- ^ Gerson, 1978, p. 162.

- ^ UN Doc A/8389 of 5 October 1971. Para 57. appearing in the Sunday Times (London) on 11 October 1970, where reference is made not only to the villages of Jalou, Beit Nuba, and Imwas, also referred to by the Special Committee in its first report, but in addition to villages like Surit, Beit Awwa, Beit Mirsem and El-Shuyoukh in the Hebron area and Jiflik, Agarith and Huseirat, in the Jordan Valley. The Special Committee has ascertained that all these villages have been completely destroyed Para 58. the village of Nebi Samwil was in fact destroyed by Israeli armed forces on March 22, 1971.

- ^ "UNRWA's Frequently Asked Questions under "Who is a Palestine refugee?" begins "For operational purposes, UNRWA has defined Palestine refugee as any person whose "normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict." Palestine refugees eligible for UNRWA assistance, are mainly persons who fulfill the above definition and descendants of fathers fulfilling the definition."" (HTML). United Nations. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Note on the Applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees to Palestinian refugees" (HTML). United Nations. 2002. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "g" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Arlene Kushner (2004). "United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East" (PDF). Israel Resource News. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); line feed character in|title=at position 39 (help) - ^ "Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees" (PDF). UNHCR. 1951 and 1967. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Pinner, Dr. Walter (1959 and 1967). How many refugees? and The Legend of the Arab Refugees. McGibbon & Kee. pp. ?.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ http://www.arts.mc.gill.ca.mepp/new-prrn/background (Palestine refugee researchnet

- ^ http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home

- ^ http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1233304645372&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FPrinter 'UNRWA staff not tested for terror ties' Jpost

- ^ http://www.mepeace.org/forum/topics/fixing-unrwa-by-james-g Repairing the UN’s Troubled System of Aid to Palestinian Refugees

- ^ http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/043/65/IMG/NR004365.pdf?OpenElement

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ "[[United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194]]" (PDF). United Nations. 1948. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite news}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ R. Brynen, 'Addressing the Palestinian Refugee Issue: A Brief Overview' (McGill University, background paper for the Refugee Coordination Forum, Berlin, April 2007), p.15, available at http://www.arts.mcgill.ca/mepp/new_prrn/research/papers/brynen-070514.pdf (11/03/08)

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/middle_east/israel_and_the_palestinians/key_documents/1682727.stm Oslo Accords Declaration of Principals

- ^ http://www.ynet.co.il/english/articles/0,7340,L-3558676,00.html 2nd Intifada forgotten