Switzerland during the World Wars: Difference between revisions

→World War I: expanded and removed tag |

→World War I: expanded and added pictures |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

During the war the Swiss border was crossed about 1,000 times by belligerents<ref name="HDS32">{{HDS|8926-3-2|World War I-1914 to 1918}}</ref> with some of these incidents occuring around the ''Dreisprachen Piz'' or Three Languages Peak (near the [[Stelvio Pass]]; languages being [[Italian (language)|Italian]], [[Romansh language|Romansh]] and [[German (language)|German]]). Switzerland had an outpost and a hotel (which was destroyed as it was used by the Austrians) on the peak. During the war, fierce battles were fought in the ice and snow of the area, with gun fire even crossing into Swiss areas at times. The three nations made an agreement not to fire over Swiss territory which jutted out in between Austria (to the north) and Italy (to the south). Instead they could fire down the pass, as Swiss territory was up and around the peak. |

During the war the Swiss border was crossed about 1,000 times by belligerents<ref name="HDS32">{{HDS|8926-3-2|World War I-1914 to 1918}}</ref> with some of these incidents occuring around the ''Dreisprachen Piz'' or Three Languages Peak (near the [[Stelvio Pass]]; languages being [[Italian (language)|Italian]], [[Romansh language|Romansh]] and [[German (language)|German]]). Switzerland had an outpost and a hotel (which was destroyed as it was used by the Austrians) on the peak. During the war, fierce battles were fought in the ice and snow of the area, with gun fire even crossing into Swiss areas at times. The three nations made an agreement not to fire over Swiss territory which jutted out in between Austria (to the north) and Italy (to the south). Instead they could fire down the pass, as Swiss territory was up and around the peak. |

||

Following the outbreak of the war, neutral Switzerland became a haven for many politicians, artists, pacifists, and thinkers<ref>{{HDS|8932-1-5|Culture during World War I}}</ref>. Berne, Zürich und Geneva became centers of debate and discussion. In Zürich two very different anti-war groups would create a lasting change on the world, the [[Bolshevik]]s and the [[Dada]]ists. |

|||

The 1917 [[Dada]] movement of [[Zürich]] was essentially a cultural reaction to the war, initiated by exiles. [[Lenin]] was also exiled in Zürich, from where he travelled directly to [[Petrograd]] to lead the [[October Revolution|Russian Revolution]]. |

|||

[[Image:Zürich - Spiegelgasse 14 - Lenin IMG 1325.jpg|thumb|left|Plaque on Lenin's house at Spiegelgasse 14 in Zürich]] |

|||

The Bolsheviks were a faction of [[Socialism|socialists]] that centered around [[Lenin]]. Following the outbreak of the war, Lenin was stunned when the large Social Democratic parties of Europe (at that time self-described as Marxist) supported their various countries’ war efforts. Lenin (against the war in his belief that the peasants and workers were fighting the battle of the [[bourgeoisie]] for them) adopted the stance that what he described as an “imperialist war” ought to be turned into a civil war between the classes. He left Austria for neutral Switzerland in 1914 following the outbreak of the war and was active in Switzerland until 1917. Following the 1917 [[February Revolution]] in Russia and the abdication of Tsar [[Nicholas II of Russia|Nicholas II]] he left Switzerland via the ''Sealed Train'' to [[Petrograd]] from where he would shortly lead the [[October Revolution]] in Russia. |

|||

[[Image:Cabaretvoltaire.jpg|thumb|Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, as it appears today]] |

|||

While the Dada art movement was also an anti-war organinzation, they used art to oppose all wars. The founders of the movement had left Germany and Romania to escape the destruction of the war. At the [[Cabaret Voltaire (Zürich)|Cabaret Voltaire]] in Zürich they but on performances expressing their disgust with the war and the interests that inspired it. By some accounts Dada coalesced on October 6, 1916 at the cabaret. The artists used abstraction to fight against the social, political, and cultural ideas of that time that they believed had caused the war. Abstraction was viewed as the result of a lack of planning and logical thought processes.<ref name="nga.gov">{{Citation | url = http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2006/dada/cities/index.shtm}}</ref>. When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zürich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities. |

|||

In 1917 Switzerland's neutrality was seriously questioned when the [[Grimm-Hoffmann Affair]] erupted. [[Robert Grimm]], a [[socialist]] politician, traveled to [[Russia]] as an [[political activism|activist]] to negotiate a [[separate peace]] between Russia and [[Germany]], in order to end the war on the Eastern Front in the interests of socialism and [[pacifism]]. Misrepresenting himself as a [[diplomat]] and an actual representative of the Swiss government, he made progress but was forced to admit fraud and return home when the Allies found out about the proposed peace deal. Neutrality was restored by the resignation of [[Arthur Hoffmann]], the [[Swiss Federal Council]]lor who had supported Grimm. |

|||

Switzerland's neutrality was seriously questioned when the [[Grimm-Hoffmann Affair]] erupted, but it was short-lived. |

|||

==Interwar period== |

==Interwar period== |

||

Revision as of 02:43, 30 December 2008

| History of Switzerland |

|---|

|

| Early history |

| Old Swiss Confederacy |

|

| Transitional period |

|

| Modern history |

|

| Timeline |

| Topical |

|

|

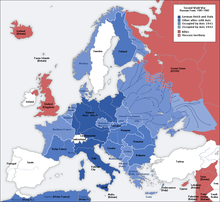

During both World War I and World War II, Switzerland managed to keep a stance of armed neutrality, and was not involved militarily. It was, however, precisely because of its neutral status, of considerable interest to all parties involved, as the scene for diplomacy, espionage, commerce, and as safe haven for refugees.

World War I

Switzerland maintained a state of armed neutrality during the war. However with the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary and the Entente Powers of France and Italy all sharing borders and populations with Switzerland, this was not easy to accomplish. From December 1914 until the spring of 1918 Swiss troops were deployed in the Jura along the French border over concern that the trench war might spill into Switzerland. Of lesser concern was the Italian border, but troops were also stationed in the Unterengadin region of Graubünden[1]. While the German speaking majority generally favored the Central Powers, the French and, later, Italian speaking population sided with the Entente Powers which would cause conflict in 1918, but keep the country out of the war. During the war Switzerland was blockaded by the Allies and therefore suffered some difficulties. However, because Switzerland was centrally located, neutral, and generally undamaged, the war allowed the growth of the Swiss banking industry[1]. For the same reasons, Switzerland became a haven for refugees and revolutionaries.

Following the organization of the army in 1907 and expansion in 1911, the Swiss Army consisted of about 250,000 men with an additional 200,000 in supporting roles[2]. The size of the Swiss military was considered by both sides in the pre-War years, especially in the Schlieffen Plan. Following an impressive showing during maneuvers in 1912 convinced both France and Germany of the professionalism of the Swiss Army.

Following the declarations of war in July 1914, on 1 August 1914 the Swiss Army was mobilized and by August 7 the newly appointed general Ulrich Wille had about 220,000 men under his command. By 11 August much of the army had been deployed along the Jura border with France. With smaller units deployed along the east and southern borders. This remained unchanged until May 1915 when Italy entered the war on the Entente side. At this point troops were deployed to the Unterengadin valley, Val Müstair and along the southern border.

Once it became clear that the Allies and Central Powers would respect Swiss neutrality, the number of troops deployed began to dropp. After September 1914, some soldiers were released to return to their farms and vital industries. In November 1916, the Swiss had only 38,000 men in the army. This number increased during the winter of 1916-17 to over 100,000 due to a proposed French attack that would cross Switzerland. When this attack failed to occur the army began to shrink again. Due to wide-spread workers' strikes, by the end of the war the army had shrunk to only 12,500 men[3].

During the war the Swiss border was crossed about 1,000 times by belligerents[3] with some of these incidents occuring around the Dreisprachen Piz or Three Languages Peak (near the Stelvio Pass; languages being Italian, Romansh and German). Switzerland had an outpost and a hotel (which was destroyed as it was used by the Austrians) on the peak. During the war, fierce battles were fought in the ice and snow of the area, with gun fire even crossing into Swiss areas at times. The three nations made an agreement not to fire over Swiss territory which jutted out in between Austria (to the north) and Italy (to the south). Instead they could fire down the pass, as Swiss territory was up and around the peak.

Following the outbreak of the war, neutral Switzerland became a haven for many politicians, artists, pacifists, and thinkers[4]. Berne, Zürich und Geneva became centers of debate and discussion. In Zürich two very different anti-war groups would create a lasting change on the world, the Bolsheviks and the Dadaists.

The Bolsheviks were a faction of socialists that centered around Lenin. Following the outbreak of the war, Lenin was stunned when the large Social Democratic parties of Europe (at that time self-described as Marxist) supported their various countries’ war efforts. Lenin (against the war in his belief that the peasants and workers were fighting the battle of the bourgeoisie for them) adopted the stance that what he described as an “imperialist war” ought to be turned into a civil war between the classes. He left Austria for neutral Switzerland in 1914 following the outbreak of the war and was active in Switzerland until 1917. Following the 1917 February Revolution in Russia and the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II he left Switzerland via the Sealed Train to Petrograd from where he would shortly lead the October Revolution in Russia.

While the Dada art movement was also an anti-war organinzation, they used art to oppose all wars. The founders of the movement had left Germany and Romania to escape the destruction of the war. At the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich they but on performances expressing their disgust with the war and the interests that inspired it. By some accounts Dada coalesced on October 6, 1916 at the cabaret. The artists used abstraction to fight against the social, political, and cultural ideas of that time that they believed had caused the war. Abstraction was viewed as the result of a lack of planning and logical thought processes.[5]. When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zürich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities.

In 1917 Switzerland's neutrality was seriously questioned when the Grimm-Hoffmann Affair erupted. Robert Grimm, a socialist politician, traveled to Russia as an activist to negotiate a separate peace between Russia and Germany, in order to end the war on the Eastern Front in the interests of socialism and pacifism. Misrepresenting himself as a diplomat and an actual representative of the Swiss government, he made progress but was forced to admit fraud and return home when the Allies found out about the proposed peace deal. Neutrality was restored by the resignation of Arthur Hoffmann, the Swiss Federal Councillor who had supported Grimm.

Interwar period

One potential result of World War I was an expansion of Switzerland itself during the Interwar Period. In a referendum held in the Austrian state of Vorarlberg on 11 May 1919 over 80% of those voting supported a proposal that the state should join the Swiss Confederation. However, this was prevented by the opposition of the Austrian Government, the Allies, Swiss liberals, the Swiss-Italians and the Swiss-French.[6]

In 1920, Switzerland joined the League of Nations.

World War II

During World War II, detailed invasion plans were drawn up by the German military command,[7] such as Operation Tannenbaum, but Switzerland was never attacked. Switzerland was able to remain independent through a combination of economic concessions to Germany, military deterrence and good fortune as larger events during the war delayed an invasion. Attempts by Switzerland's small Nazi party to cause an Anschluss with Germany failed miserably, largely due to Switzerland's multicultural heritage, strong sense of national identity, and long tradition of direct democracy and civil liberties. The Swiss press vigorously criticized the Third Reich, often infuriating its leadership. Under General Henri Guisan, a massive mobilization of militia forces was ordered. The Swiss military strategy was changed from one of static defense at the borders, to a strategy of organized long-term attrition and withdrawal to strong, well-stockpiled positions high in the Alps known as the Réduit. This controversial strategy was essentially one of deterrence. The idea was to make clear to the Third Reich that the cost of an invasion would be very high. During an invasion, the Swiss Army would cede control of the economic heartland and population centers, but retain control of crucial rail links and passes in the Réduit. Switzerland was an important base for espionage by both sides in the conflict and often mediated communications between the Axis and Allied powers by serving as a protecting power. Though neutral the Swiss were very Pro-allied and were quite disturbed by any type of Nazi sympathizer within the military ranks. Sympathizers were normally given very dismal jobs such as prison guards and other types of remedial work. Despite public and political pressure some higher ranking officers within the Swiss Army were sympathetic towards the Nazis, notably Colonel Arthur Fonjallaz and Colonel Eugen Bircher, who led the Schweizerischer Vaterländischer Verband.

Over the course of the war, Switzerland interned 300,000 refugees. 104,000 of these were foreign troops held according to the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers outlined in the Hague Conventions. The rest were foreign civilians and were either interned or granted tolerance or residence permits by the cantonal authorities. Refugees were not allowed to hold jobs. 60,000 of the refugees were civilians escaping persecution by the Nazis. Of these, 26,000 to 27,000 were Jews.[8] At the beginning of the war, Switzerland had a Jewish population of about 25,000 [9] and a total population of about 4 million. By the end of the war, there were over 115,000 refuge-seeking people of all categories in Switzerland, representing the maximum number of refugees at any one time.[8] On those refused entry, a Swiss government representative said, "Our little lifeboat is full." Although Switzerland harbored more Jewish refugees than any other country, between 10,000 and 25,000 civilian refugees, mainly Jewish, were refused entry due to the already dwindling supplies.

At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Switzerland immediately began to mobilize for a possible invasion. The entire country was fully mobilized in only three days. The Swiss government began to fortify positions throughout the country. The army and militias total strength grew to over 500,000.

Nazi Germany repeatedly violated Swiss airspace. During the Invasion of France, German aircraft violated Swiss airspace no fewer than 197 times.[9] In several air incidents, the Swiss (using 10 Bf-109 D, 80 Bf-109 E fighters bought from Germany and some Morane-Saulnier M.S.406s built under license in Switzerland), shot down 11 Luftwaffe planes between 10 May 1940 and 17 June 1940.[9] Germany protested diplomatically on 5 June 1940, and with a second note on 19 June 1940 which contained clear threats. Hitler was especially furious when he saw that German equipment was shooting down German pilots. He said they would respond "in another matter".[9] On 20 June 1940, the Swiss air force was ordered to stop intercepting planes violating Swiss airspace. Swiss fighters began to instead force intruding aircraft to land at Swiss airfields. Anti-aircraft units still operated. Later, Hitler unsuccessfully sent saboteurs to destroy airfields.[10]

Allied aircraft also intruded on Swiss airspace during the war, mostly Allied bombers returning from raids over Italy and Germany that had been damaged and whose crews preferred internment by the Swiss to becoming prisoners of war. Over a hundred Allied aircraft and their crews were interned.[11]

Switzerland, surrounded by Axis controlled territory, also suffered from Allied bombings during the war; most notably the accidental bombing of Schaffhausen by American planes on April 1 1944. It was mistaken for a nearby German town and 40 people were killed and over 50 buildings destroyed.[12][11][13]

The bombing limited much of the leniency the Swiss had to allied airspace violations. Eventually, the problem became so bad that the Swiss authorized fighter attacks on belligerent U.S. aircraft. [citation needed] Victims of these mistaken bombings were not limited to Swiss civilians however, but included the often confused American aircrews, shot down by the Swiss fighters as well as several Swiss fighters shot down by American airman. In February 1945, 18 civilians were killed by Allied bombs dropped over Stein am Rhein, Vals, and Rafz. Perhaps the most notorious incident[citation needed] came on March 4, 1945, when both Basel and Zurich were accidentally bombed by Allied aircraft. The attack on Basel's railway station led to the destruction of a passenger train, but no casualties were reported. However, a B-24 Liberator dropped its bomb load over Zurich, destroying two buildings and killing 5 civilians. The aircraft's crew believed that they were attacking Freiburg in Germany.[13] As John Helmreich points out, Sincock and Balides, in choosing a target of opportunity, "...missed the marshalling yard they were aiming for, missed the city they were aiming for, and even missed the country they were aiming for."

The Swiss reaction, although somewhat skeptical, was to treat these violations of their neutrality as 'accidents'. The United States was warned that single aircraft would be forced down, and would still be allowed to seek refuge, while bomber formations in violation of airspace would be intercepted. While American politicians and diplomats tried to minimise the political damage caused by these incidents, others took a more hostile view. Some senior commanders argued that, as Switzerland was 'full of German sympathisers', it deserved to be bombed.[citation needed] General Harris Hall even suggested that it was the Germans themselves who were flying captured allied planes over Switzerland in an attempt to gain a propaganda victory.[citation needed] However the U.S. eventually apologized for the violations.

Danger from U.S. Bombers came not only from accidental bombings, but from the aircraft themselves. In many cases once a crippled bomber reached Switzerland and was out of enemy territory crews would often bail out leaving the aircraft to continue until it crashed.

Controversy over financial relationships with Nazi Germany

Switzerland's trade was blockaded by both the Allies and by the Axis. Both sides openly exerted pressure on Switzerland not to trade with the other. Economic cooperation and extension of credit to the Third Reich varied according to the perceived likelihood of invasion, and the availability of other trading partners. Concessions reached their zenith after a crucial rail link through Vichy France was severed in 1942, leaving Switzerland completely surrounded by the Axis. Switzerland relied on trade for half of its food and essentially all of its fuel, but controlled vital trans-alpine rail tunnels between Germany and Italy. Switzerland's most important exports during the war were precision machine tools, watches, jewel bearings (used in bombsights), electricity, and dairy products. During World War Two, the Swiss franc was the only remaining major freely convertible currency in the world,[citation needed] and both the Allies and the Germans sold large amounts of gold to the Swiss National Bank. Between 1940 and 1945, the German Reichsbank sold 1.3 billion francs worth of gold to Swiss Banks in exchange for Swiss francs and other foreign currency.[8] Hundreds of millions of francs worth of this gold was monetary gold plundered from the central banks of occupied countries. 581,000 francs of "Melmer" gold taken from Holocaust victims in eastern Europe was sold to Swiss banks.[8] In total, trade between Germany and Switzerland contributed about 0.5% to the German war effort and did not significantly lengthen the war.[8]

In the 1990s, controversy over a class-action lawsuit brought in Brooklyn, New York over Jewish assets in Holocaust-era bank accounts prompted the Swiss government to commission the most recent and authoritative study of Switzerland's interaction with the Nazi regime. The final report by this independent panel of international scholars, known as the Bergier Commission,[8] was issued in 2002.

References

- ^ a b World War I-Introduction in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ World War I-Preparation in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.Error in template * invalid parameter (Template:HDS): "1"

- ^ a b World War I-1914 to 1918 in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.Error in template * invalid parameter (Template:HDS): "1"

- ^ Culture during World War I in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.Error in template * invalid parameter (Template:HDS): "1"

- ^ http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2006/dada/cities/index.shtm

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ C2D - Centre d'études et de documentation sur la démocratie directe

- ^ Let's Swallow Switzerland by Klaus Urner (Lexington Books, 2002).

- ^ a b c d e f The Bergier Commission Final Report

- ^ a b c d The Neutrals by Time Life (Time Life Books, 1995).

- ^ Essential Militaria, Nicholas Hobbes, 2005

- ^ a b The Diplomacy of Apology: U.S. Bombings of Switzerland during World War II

- ^ Schaffhausen im Zweiten Weltkrieg

- ^ a b US-Bomben auf Schweizer Kantone

Further reading

- 1. Switzerland Under Siege 1939-1945, Leo Schelbert, Editor ISBN 0-89725-414-7

- 2. Between the Alps and a Hard Place, Switzerland in World War II and the Rewriting of History, Angelo M. Codevilla ISBN 0-89526-238-X