Christianization: Difference between revisions

Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) redid lead. I can't tell if it's any better or not. I just hope the reviewer likes it. |

Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) In response to GA failure and reviewer critique, I have redone the article from a new perspective that is hopefully more focused. It has most of its original content {{Copied}} into this one with a couple sentences here and there copied from Christianity and paganism, and maybe History of Christianity. It isn't perfect, references need updating now, and I will do that immediately. Tag: harv-error |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{History of religion}} |

{{History of religion}} |

||

{{Christianity|expanded=Related}} |

{{Christianity|expanded=Related}} |

||

'''Christianization''' or '''Christianisation''' is a term used to describe conversion to Christianity. An individual's Christianization can be said to begin when they adopt certain designated beliefs and become part of a community who share those beliefs. Throughout history, a long list of previously pagan songs, practices, spaces and places have been Christianized through ritual rededication and redefinition of their purpose or meaning in Christian terms. Christianization occurs in a nation when common lifestyles and community activities reflect some measure of Christian ethics and goals. |

|||

It began when individual followers of [[Jesus]] formed communities in first century Palestine. Christianization spread through the Roman Empire and neighboring empires in the next few centuries, converting most of the Germanic barbarian peoples who would form the ethnic communities that would become the future nations of Europe. The first countries to make Christianity their state religion were [[Kingdom of Armenia (antiquity)|Armenia]], [[Kingdom of Iberia|Georgia]], [[Kingdom of Aksum|Ethiopia and Eritrea]] in the fourth century; those societies had been voluntarily Christianized before that designation was made official. By the end of the fifth and beginning of the sixth century, the Eastern Roman Empire was finally fully Christianized, but this was imposed by the Emperor [[Justinian I]]. Visigothic Spain of the seventh century was the first to require Christian baptism of all its citizens. |

|||

'''Christianization''' (or '''Christianisation''') is a term used to describe conversion to Christianity. An individual's Christianization begins when they adopt certain designated beliefs and become part of a community which shares those beliefs. Throughout history, a long list of previously pagan songs, practices, spaces and places have been (voluntarily and involuntarily) Christianized through ritual rededication and redefinition of their purpose or meaning in Christian terms. Christianization occurs in a nation when common lifestyles and community activities reflect some measure of Christian ethics and goals. |

|||

In Central and Eastern Europe of the 8th and 9th centuries, Christianization began with the aristocracy and was an integral part of the political centralization of the new nations being formed.{{sfn|Štefan|2022|p=101}} [[Bulgaria]], [[Bohemia]] (which became [[Czechoslovakia]]), the [[Serbia|Serbs]] and the [[Croatia|Croats]], along with [[Hungary]], and [[Poland]], voluntarily joined the Western, Latin church, sometimes pressuring their people to follow. Christianization often took centuries to accomplish. The Christianization of the [[Kievan Rus']], (the ancestors of [[Belarus]], [[Russia]], and [[Ukraine]]), began in the tenth century and used coercion to Christianize the population, as it was a state church with state control of religion. The two centuries around the turn of the first millennium brought Europe's most significant Christianization of the Middle Ages.{{sfn|Klaniczay|2004|p=99}} What had been two dangerous and aggressive enemies, (the Scandinavian Vikings on the northern borders, and the Hungarians in the east), voluntarily adopted Christianity and founded kingdoms that sought a place among the European states.{{sfn|Klaniczay|2004|p=99}} |

|||

Christianization began when the early individual followers of [[Jesus]] became itinerant preachers in response to the command recorded in Matthew 28:19, (sometimes called the [[Great Commission]]), to go to all the nations of the world and preach the [[The Gospel|good news]] about Jesus. <ref>Plummer, Robert L. "The Great Commission in the New Testament." The Challenge of the Great Commission: Essays on God’s Mandate for the Local Church (2005): pages 33-47.</ref> It spread through the Roman Empire, Europe of the Middle Ages, and in the twenty-first century, has become a global phenomenon. |

|||

The Northern Crusades, from 1147 to 1316, form a unique chapter in Christianization. They were largely political, led by local princes against their own enemies, for their own gain, and conversion by these princes was almost always a result of armed conquest.{{sfn|Leighton|2021|pp=393–408}} Colonialism and imperialism has both aided and inhibited Christianization. Modern Christianization has become a global phenomenon. |

|||

===Individual conversion=== |

|||

==Christianization== |

|||

{{Main|Conversion to Christianity}} |

|||

The first stage of Christianization begins when personal conversions take place. For nations, this has historically been associated with missions and missionaries, and is therefore called the mission period.{{sfn|Ščavinskas|2017|p=57}} |

|||

James P. Hanigan writes that individual conversion is the foundational experience and the central message of Christianization.<ref name="Hanigan">{{cite journal|last=Hanigan|first=James P.|title=Conversion and Christian Ethics|url=http://theologytoday.ptsem.edu/apr1983/v40-1-article3.htm |journal=Theology Today|volume=40|number=1|date=April 1983|access-date=2009-06-17 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120502195942/http://theologytoday.ptsem.edu/apr1983/v40-1-article3.htm |archive-date=2012-05-02 }}</ref>{{rp|p=25}} The normative form of Christian conversion begins with an experience of being thrown off balance through cognitive and psychological disequilibrium, followed by an awakening of consciousness and a new awareness of God.<ref name="Hanigan"/>{{rp|pp=28-29}} Hanigan compares it to "death and rebirth, a turning away..., a putting off of the old..., a change of mind and heart".<ref name="Hanigan"/>{{rp|pp=25-26}} The person responds by acknowledging and confessing personal lostness and sinfulness, and then accepting a [[Universal call to holiness|call to holiness]] thus restoring balance.<ref name="Hanigan"/>{{rp|pp=25-28}} |

|||

====Baptism==== |

|||

The second stage is consolidation. The convert's way of life begins to transform.{{sfn|Ščavinskas|2017|p=59}} Their world out-look changes and former customs, such as burial customs, are changed to reflect Christian practices.{{sfn|Ščavinskas|2017|p=59}} On a societal basis, Christian communities form; the first dedicated church structures are built; monasteries and dioceses are established; and the first parishes are created.{{sfn|Ščavinskas|2017|p=59}} During this stage, Christianization establishes schools and spreads education, translates Christian writings to local languages, often developing a script to do so, thereby creating the first literature of what had been a pre-literate culture.{{sfn|Puspitasari|2013|pp=87-88}} |

|||

{{Main|Baptism}} |

|||

[[File:Piero, battesimo di cristo 04.jpg|thumb|Piero,_battesimo_di_cristo_04|baptism of Christ by Piero]] |

|||

Jesus began his ministry after his baptism by [[John the Baptist]] which can be dated to approximately AD 28–35 based on references by the Jewish historian Josephus in his ([[s:The Antiquities of the Jews/Book XVIII#Chapter 5|''Antiquities'' 18.5.2]]).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gillman |first1=Florence Morgan |title=Herodias: At Home in that Fox's Den |date=2003 |publisher=Liturgical Press |isbn=978-0-8146-5108-7 |url=https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=rFRFe8QdO1gC |language=en |pages=25–30}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hoehner |first1=Harold W. |title=Herod Antipas |date=1983 |volume=17 |series=Contemporary evangelical perspectives |publisher=Zondervan |isbn=978-0-310-42251-8 |pages=125–127}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Novak |first1=Ralph Martin |title=Christianity and the Roman Empire: Background Texts |date=2001 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-1-56338-347-2 |url=https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TNWkzgEACAAJ |language=en |pages=302–303}}</ref>{{sfn|Hoehner|1978|pp=29–37}} |

|||

Individual conversion is followed by the initiation rite of baptism.{{sfn|McKinion|2001|p=5}} In Christianity's earliest communities, candidates for baptism were introduced by someone willing to stand [[surety]] for their character and conduct. Baptism created a set of responsibilities within the Christian community.{{sfn|MacCormack|1997|p=655}} Candidates for baptism were instructed in the major tenets of the faith, examined for moral living, sat separately in worship, were not yet allowed to receive the communion eucharist, but were still generally expected to demonstrate commitment to the community, and obedience to [[Christ (title)|Christ]]'s commands, before being accepted into the community as a full member. This could take months to years.{{sfn|McKinion|2001|pp=5-6}} |

|||

The third step in the process of Christianization involves the interchange that occurs when two cultural systems interconnect. Christianization has never been a one-way process.{{sfn|Scourfield|2007|p=2}}{{refn|group=note| [[Michele R. Salzman|Michelle Salzman]] has shown that in the process of converting the Roman Empire's aristocracy, Christianity absorbed the values of that aristocracy.{{sfn|Salzman|2002|pp=200-219}} Several early Christian writers, including Justin (2nd century), Tertullian, and Origen (3rd century) wrote of Mithraists copying Christian beliefs.{{sfn|Abruzzi|2018|p=24}} Christianity adopted aspects of Platonic thought, names for months and days of the week – even the concept of a seven-day week – from Roman paganism.{{sfn|Rausing|1995|p=229}}{{sfn|Scourfield|2007|pp=18; 20-22}}}} According to archaeologist Anna Collar, when groups of people with different ways of life come into contact with each other, they naturally exchange ideas and practices.{{sfn|Collar|2013|pp=1-10}} This is sometimes referred to as syncretism, but syncretism is a controversial concept, so instead, many scholars use the terms inculturation and acculturation instead.{{sfn|Ščavinskas|2017|p=61}} |

|||

The normative practice in the ancient church was baptism by immersion of the whole head and body of an adult, with the exception of infants in danger of death, until the fifth or sixth century.<ref>Jensen, Robin M. "Material and Documentary Evidence for the Practice of Early Christian Baptism." Journal of Early Christian Studies, vol. 20 no. 3, 2012, p. 371-405. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/earl.2012.0019.</ref>{{rp|p=371}} Historian [[Phillip Schaff]] has written that sprinkling, or pouring of water on the head of a sick or dying person, where immersion was impractical, was also practiced in ancient times and up through the twelfth century.<ref name="Schaff 1882">{{cite book |last1=Schaff |first1=Philip |title=History of the Christian Church |date=1882 |publisher=C. Scribner's Sons}}</ref>{{rp|p=469}} Infant baptism was controversial for the Protestant Reformers, but according to Schaff, it was practiced by the ancients and is neither required nor forbidden in the New Testament.<ref name="Schaff 1882"/>{{rp|p=470}} |

|||

Anthropologist Aylward Shorter defines inculturation as the "ongoing dialogue" between Christian teachings and local culture. The church adapts itself to a particular local cultural context just as local culture and places are also adapted to the church.{{sfn|Shorter|2006|p=11}} This has at times involved appropriation, removal and/or redesignation of aspects of native religion and former sacred spaces allowing them to find a place in the new religious system.{{sfn|Gregory|1986|p=234}} In some cases the survival of local custom was encouraged by Christian missionaries, while other aspects of traditional religion survived despite the opposition of the missionaries.{{sfn|Gregory|1986|p=234}} |

|||

[[File:Baptism at Eastside Christian Church2018.jpg|thumb|Baptism_at_Eastside_Christian_Church2018|modern baptism at Eastside Christian church]] |

|||

====Eucharist==== |

|||

Variations in the results, according to Clark, are based largely on local ethnic composition, political structure and the local locus of power.{{sfn|Clark|1979|p=377}} Ancient Germanic societies tended to be communal by nature rather than oriented around individuality, and loyalty to the king meant the conversion of the ruler was generally followed by the mass conversion of his subjects.{{sfn|Cusack|1998|p=35}} Clark has also written that different methods were used by different individual missionaries contributing to differing results.{{sfn|Clark|1979|p=394}} |

|||

{{Main|Eucharist }} |

|||

The celebration of the eucharist (also called communion) was the common unifier for early Christian communities, and remains one of the most important of Christian rituals. Early Christians believed the Christian message, the celebration of communion (the Eucharist) and the rite of baptism came directly from [[Jesus]] of [[Nazareth]].{{sfn|McKinion|2001|p=5}} |

|||

[[File:Brooklyn Museum - The Communion of the Apostles (La communion des apôtres) - James Tissot.jpg|thumb|Brooklyn_Museum_-_The_Communion_of_the_Apostles_(La_communion_des_apôtres)_-_James_Tissot|The Communion of the Apostles by James Tissot]] |

|||

Father Enrico Mazza writes that the "Eucharist is an imitation of the Last Supper" when Jesus gathered his followers for their last meal together the night before he was arrested and killed.<ref name="Baldwin 2000">BALDOVIN, J. F. THE CELEBRATION OF THE EUCHARIST: THE ORIGIN OF THE RITE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF ITS INTERPRETATION (Book Review). Theological Studies, [s. l.], v. 61, n. 3, p. 583, 2000. DOI 10.1177/004056390006100330. Disponível em: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lkh&AN=3505011&site=eds-live&scope=site. Acesso em: 5 ago. 2023.</ref>{{rp|p=583}} While the majority share the view of Mazza, there are others such as New Testament scholar [[Bruce Chilton]], who argue that there were multiple origins of the Eucharist.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Armstrong |first1=John H. |title=Understanding Four Views on the Lord's Supper |date=2007 |publisher=Zondervan |isbn=9780310262688 |pages=13-15}}</ref><ref name="Baldwin 2000"/>{{rp|p=584}} |

|||

In the Middle Ages, the Eucharist came to be understood as a sacrament (wherein God is present) that evidenced Christ's sacrifice, and the prayer given with the rite was to include two [[Strophe|strophes]] of thanksgiving and one of petition. The prayer later developed into the modern version of a narrative, a memorial to Christ and an invocation of the Holy Spirit.<ref name="Baldwin 2000"/>{{rp|p=583}} |

|||

Anthropologist Jerry E. Clark writes: "Acculturation has been defined as the changes that occur in one or both cultures when two different cultures come in contact. In the case of missionaries and the American Indians, the process of acculturation was purposely one-sided."{{sfn|Clark|1979|p=377}} Recent anthropological work on acculturation has led contemporary scholars to write that its traditional definition can only be used when both societies involved in exchange have some autonomy.{{sfn|Berkhofer|2014|pp=x-xi}} In the case of a loss of political autonomy, as happened with Native Americans, directed or forced acculturation produces an alternative definition.{{sfn|Berkhofer|2014|pp=x-xi}} [[Robert F. Berkhofer]] references E. A. Hobble's definition as saying that acculturation under directed contact is "the process of interaction between two societies by which the culture of the society in subordinate position is drastically modified to conform to the culture of the dominant society."{{sfn|Berkhofer|2014|p=xi}} |

|||

====[[Confirmation]]==== |

|||

History connects [[Christianity and colonialism|Christianization with colonialism]], especially but not limited to the [[New World]] and other regions subject to [[settler colonialism]].{{sfn|Clark|1979|pp=377-380}} History also connects Christianization with opposition to colonialism. African historian [[Lamin Sanneh]] writes that there is an equal amount of evidence of both missionary support and missionary opposition to colonialism through "protest and resistance both in the church and in politics".{{sfn|Sanneh|2007|p=134-137}}<blockquote> "Despite their role as allies of the empire, missions also developed the vernacular that inspired sentiments of national identity and thus undercut Christianity's identification with colonial rule".{{sfn|Sanneh|2007|p=271}}</blockquote> |

|||

[[File:(1918) Cape Mount, Confirmation Class.jpg|thumb|(1918)_Cape_Mount,_Confirmation_Class|Confirmation class of 1918 at Cape Mount]] |

|||

During the Middle Ages, confirmation was added to the rites of initiation.<ref name="Alfsvåg, K. (2022)">Alfsvåg, K. (2022). The Role of Confirmation in Christian Initiation. Journal of Youth and Theology (published online ahead of print 2022). https://doi.org/10.1163/24055093-bja10036</ref>{{rp|p=1}} While baptism, instruction, and Eucharist have remained the essential elements of initiation in all Christian communities, <blockquote>Some see baptism, confirmation, and first communion as different elements in a unified rite through which one becomes a part of the Christian |

|||

church. Others consider confirmation a separate rite which may or may not be considered a condition for becoming a fully accepted member of the church in the sense that one is invited to take part in the celebration of the Eucharist. Among those who see confirmation as a separate rite some see it as a sacrament, while others consider it a combination of intercessory prayer and graduation ceremony after a period of instruction.</blockquote> |

|||

===Christianization of places and practices=== |

|||

''Integration'' happened when an individual engaged both their heritage culture and the larger society; ''[[cultural assimilation|assimilation]]'' or ''separation'' occurred when an individual became oriented exclusively to one or the other culture. Orientation to neither culture is ''marginalization''.{{sfn|Sam|Berry|2010|p=abstract}} In the [[Late Middle Ages]], and later colonialism, the mixture of religion with politics led to some instances of forced conversion by the sword, [[racialism]] and the marginalization of entire groups.{{sfn|Sam|Berry|2010|p=abstract}} |

|||

{{Main|Christianized sites}} |

|||

Christianization has at times involved appropriation, removal and/or redesignation of aspects of native religion and former sacred spaces. This was allowed, or required, or sometimes forbidden by the missionaries involved.{{sfn|Gregory|1986|p=234}} The church adapts to its local cultural context, just as local culture and places are adapted to the church, or in other words, Christianization has always worked in both directions: Christianity absorbs from native culture as it is absorbed into it.{{sfn|Shorter|2006|p=11}}<ref name="Robert 2009">{{cite book |last1=Robert |first1=Dana L. |title=Christian Mission: How Christianity Became a World Religion |date=2009 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=9780631236191 |edition=illustrated}}</ref>{{rp|p=177}} |

|||

When Christianity spread beyond Judaea, it first arrived in [[Jewish diaspora]] communities.{{sfn|Bokenkotter|2007|p=18}} The Christian church was modeled on the synagogue, and Christian philosophers synthesized their Christian views with Semitic monotheism and Greek thought.{{sfn|Praet|1992–1993|p=108}}{{sfn|Boatwright|Gargola|Talbert|2004|p=426}} Christianity adopted aspects of Platonic thought, names for months and days of the week – even the concept of a seven-day week – from Roman paganism.{{sfn|Rausing|1995|p=229}}{{sfn|Scourfield|2007|pp=18; 20-22}} |

|||

==Ancient (Ante-Nicaean) Christianity (1st to 3rd centuries)== |

|||

[[File:Eucharistic bread.jpg|thumb|Eucharistic_bread|early depiction of Eucharist celebration found in catacombs beneath Rome]] |

|||

{{Main|Early Christianity|Acts of the Apostles|Historiography of the Christianization of the Roman Empire}} |

|||

Christian art in the catacombs beneath Rome rose out of a reinterpretation of Jewish and pagan symbolism.{{sfn|Goodenough|1962|p=138}}.{{sfn|Testa|1998|p=80}} While many new subjects appear for the first time in the Christian catacombs - i.e. the Good Shepherd, Baptism, and the Eucharistic meal – the Orant figures (women praying with upraised hands) probably came directly from pagan art.{{sfn|Testa|1998|p=82}}{{sfn|Goodenough|1962|p=125}}{{refn|group=note|The [[Ichthys]], Christian Fish, also known colloquially as the Jesus Fish, was an early Christian symbol. Early Christians used the Ichthys symbol to identify themselves as followers of Jesus Christ and to proclaim their commitment to Christianity. Ichthys is the Ancient Greek word for "fish," which explains why the sign resembles a fish;{{sfn|Fairchild|2021}} the Greek word ιχθυς is an [[acronym and initialism|acronym]] for the phrase transliterated as "Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter", that is, "Jesus Christ, God's Son, the Savior". There are several other possible connections with Christian tradition relating to this symbol: that it was a reference to the [[feeding of the multitude]]; that it referred to some of [[Twelve Apostles|the apostles]] having previously been fishermen; or that the word ''Christ'' was pronounced by Jews in a similar way to the Hebrew word for ''fish'' (though ''Nuna'' is the normal [[Aramaic]] word for fish, making this seem unlikely).{{sfn|Fairchild|2021}}}} |

|||

{{See also|Early centers of Christianity#Rome}} |

|||

[[File:Distribution of the documented presence of Christian congregations in the first three centuries.tif|upright=1.5|thumb|Map of the Roman empire with distribution of Christian congregations displayed for each century|alt=this is a map showing how and where congregations formed ins the first three centuries]] |

|||

[[Bruce Forbes|Bruce David Forbes]] says that "Some way or another, Christmas was started to compete with rival Roman religions, or to co-opt the winter celebrations as a way to spread Christianity, or to baptize the winter festivals with Christian meaning in an effort to limit their [drunken] excesses. Most likely all three".{{sfn|Forbes|2008|p=30}} [[Michele R. Salzman|Michelle Salzman]] has shown that, in the process of converting the Roman Empire's aristocracy, Christianity absorbed the values of that aristocracy.{{sfn|Salzman|2002|pp=200-219}} |

|||

===Early method=== |

|||

{{Main|Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation}} |

|||

Christianization began in the Roman Empire in Jerusalem around 30–40 AD, spreading outward quickly. The Church in Rome was founded by [[Saint Peter|Peter]] and [[Paul the Apostle|Paul]] in the 1st century.{{sfn|Burton|2018|p=129}} There is agreement among twenty-first century scholars that Christianization of the Roman Empire in its first three centuries did not happen by imposition.{{sfn|Runciman|2004|p=6}} Christianization of this period was the cumulative result of multiple individual decisions and behaviors.{{sfn|Collar|2013|p=6}} |

|||

Some scholars have suggested that characteristics of some pagan gods — or at least their roles — were transferred to Christian saints after the fourth century.{{sfn|Kloft|2010|p=25}} [[Demetrius of Thessaloniki]] became venerated as the patron of agriculture during the Middle Ages. According to historian Hans Kloft, that was because the Eleusinian Mysteries, Demeter's cult, ended in the 4th century, and the Greek rural population gradually transferred her rites and roles onto the Christian saint Demetrius.{{sfn|Kloft|2010|p=25}} |

|||

While enduring three centuries of on-again, off-again persecution, from differing levels of government ranging from local to imperial, Christianity had remained 'self-organized' and without central authority.{{sfn|Collar|2013|pp=6; 36; 39}} In this manner, it reached an important [[Threshold model|threshold of success]] between 150 and 250, when it moved from less than 50,000 adherents to over a million, and became self-sustaining and able to generate enough further growth that there was no longer a viable means of stopping it.{{sfn|Collar|2013|p=325}}{{sfn|Harnett|2017|pp=200; 217}}{{sfn|Hopkins|1998|p=193}}{{sfn|Runciman|2004|page=3}} Scholars agree there was a significant rise in the absolute number of Christians in the third century.{{sfn|Runciman|2004|p=4}} |

|||

The Roman Empire cannot be considered to have been Christianized before Justinian I in the sixth century.{{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=652-653}} Instead, there was a vigorous public culture shared by polytheists, Jews and Christians alike.{{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=652-653}} By the time a fifth-century pope attempted to denounce the [[Lupercalia]] as 'pagan superstition', religion scholar [[Elizabeth A. Clark|Elizabeth Clark]] says "it fell on deaf ears".{{sfn|Clark|1992|pp=543–546}} In Historian [[Robert Austin Markus|R. A. Markus's]] reading of events, this marked a colonialization by Christians of pagan values and practices.{{sfn|Markus|1990|pp=141–142}} For Alan Cameron, the mixed culture that included the continuation of the circuses, amphitheaters and games – sans sacrifice – on into the sixth century involved the secularization of paganism rather than appropriation by Christianity.{{sfn|Cameron|2011|pp=8–10}} |

|||

===Characteristics=== |

|||

[[File:Saint James the Just.jpg|thumb|right|[[James, brother of Jesus|James the Just]], whose judgment was adopted in the Apostolic Decree of {{bibleverse||Acts|15:19–29}}, c. 50 AD|alt=stylized portrait of Jame the Just]] |

|||

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories.{{sfn|Meeks|2003|p=79}} Many scholars have seen this inclusivity as the primary reason for Christianization's early success.{{sfn|Praet|1992|p=49}} The [[Council of Jerusalem|Apostolic Decree]] helped to establish Ancient Christianity as unhindered by either ethnic or geographical ties.{{refn|group=note| The [[Council of Jerusalem]] (around 50 AD) agreed the lack of [[circumcision]] could not be a basis for excluding [[Gentile]] believers from membership in the Jesus community. They instructed converts to avoid "pollution of idols, fornication, things strangled, and blood" ([[KJV]], Acts 15:20–21).{{sfn|Fahy|1963|p=249}} These were put into writing, distributed ([[KJV]] Acts 16:4–5) by messengers present at the council, and were received as an encouragement.{{sfn|Fahy|1963|p=257}}}} Christianity was experienced as a new start, and was open to both men and women, rich and poor. Baptism was free. There were no fees, and it was intellectually [[Egalitarianism|egalitarian]], making [[philosophy]] and [[ethics]] available to ordinary people including those who might have lacked [[literacy]].{{sfn|Praet|1992|p=45–48}} [[Homogeneity and heterogeneity|Heterogeneity]] characterized the groups formed by [[Paul the Apostle]], and the role of [[women]] was much greater than in any of the forms of Judaism or paganism in existence at the time.{{sfn|Meeks|2003|p=81}} |

|||

Several early Christian writers, including [[Justin Martyr|Justin]] (2nd century), [[Tertullian]], and [[Origen]] (3rd century) wrote of Mithraists copying Christian beliefs and practices.{{sfn|Abruzzi|2018|p=24}} |

|||

Ante-Nicaean Christianity was also highly exclusive.{{sfn|Trebilco|2017|pp=85, 218}} Believing was the crucial and defining characteristic that set a "high boundary" that strongly excluded the "[[Infidel|unbeliever]]".{{sfn|Trebilco|2017|pp=85, 218}} [[Keith Hopkins]] asserts: "It is this exclusivism, idealized or practiced, which marks Christianity off from most other religious groups in the ancient world".{{sfn|Hopkins|1998|p=187}} The early Christian had exacting moral standards that included avoiding contact with those that were seen as still "in bondage to the Evil One": ([[s:Bible (King James)/2 Corinthians#2 Corinthians 6|2 Corinthians 6:1-18]]; [[s:Bible (King James)/1 John#1 John 2|1 John 2: 15-18]]; [[s:Bible (King James)/Revelation#Revelation 18|Revelation 18: 4]]; II Clement 6; Epistle of Barnabas, 1920).{{sfn|Green|2010|pp=126–127}} In Daniel Praet's view, the exclusivity of Christian monotheism formed an important part of its success, enabling it to maintain its independence in a society that [[Syncretism|syncretized]] religion.{{sfn|Praet|1992|p=68;108}} |

|||

In both Jewish and Roman tradition, genetic families were buried together, but an important cultural shift took place in the way Christians buried one another: they gathered unrelated Christians into a common burial space, as if they really were one family, "commemorated them with homogeneous memorials and expanded the commemorative audience to the entire local community of coreligionists" thereby redefining the concept of family.{{sfn|Yasin|2005|p=433}}{{sfn|Hellerman|2009|p=6}} |

|||

[[Christian monasticism]] emerged in the third century, and [[monks]] soon became crucial to the process of Christianization. Their numbers grew such that, "by the fifth century, monasticism had become a dominant force impacting all areas of society".{{sfn|Crislip|2005|p=1-3}}{{sfn|Gibbon|1776|loc=Chapter 38}} |

|||

=== |

=====Temple conversion within Roman Empire===== |

||

In 301, [[Christianization of Armenia|Armenia]] became the first kingdom in history to adopt Christianity as an official state religion.{{sfn|Cohan|2005|p=333}} The transformations taking place in these centuries of the Roman Empire had been slower to catch on in Caucasia. Indigenous writing did not begin until the fifth century, there was an absence of large cities, and many institutions such as monasticism did not exist in Caucasia until the seventh century.{{sfn|Aleksidze|2018|p=138}} Scholarly consensus places the Christianization of the Armenian and Georgian elites in the first half of the fourth century, although Armenian tradition says Christianization began in the first century through the Apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew.{{sfn|Aleksidze|2018|p=135}} This is said to have eventually led to the conversion of the Arsacid family, (the royal house of Armenia), through [[St. Gregory the Illuminator]] in the early fourth century.{{sfn|Aleksidze|2018|p=135}} |

|||

Christianization took many generations and was not a uniform process.{{sfn|Thomson|1988|p=35}} Robert Thomson writes that it was not the officially established hierarchy of the church that spread Christianity in Armenia. "It was the unorganized activity of wandering holy men that brought about the Christianization of the populace at large".{{sfn|Thomson|1988|p=45}} The most significant stage in this process was the development of a script for the native tongue.{{sfn|Thomson|1988|p=45}} |

|||

Scholars do not agree on the exact date of [[Christianization of Georgia]], but most assert the early 4th century when [[Mirian III]] of the [[Kingdom of Iberia]] (known locally as [[Kartli]]) adopted Christianity.{{sfn|Rapp|2007|p=138}} According to medieval [[Georgian Chronicles]], Christianization began with [[Andrew the Apostle]] and culminated in the evangelization of Iberia through the efforts of a captive woman known in Iberian tradition as [[Saint Nino]] in the fourth century.{{sfn|Aleksidze|2018|pp=135-136}} Fifth, 8th, and 12th century accounts of the conversion of Georgia reveal how pre-Christian practices were taken up and reinterpreted by Christian narrators.{{sfn|Horn|1998|p=262}} |

|||

In 325, the [[Kingdom of Aksum]] (Modern Ethiopia and Eritrea) became the second country to declare Christianity as its official state religion.{{sfn|Brita|2020|p=252}} |

|||

==Late antiquity (4th–5th centuries)== |

|||

{{main|Christianization of the Roman Empire|Spread of Christianity}} |

{{main|Christianization of the Roman Empire|Spread of Christianity}} |

||

{{further|Constantine I and Christianity|Persecution of paganism under Theodosius I}} |

{{further|Constantine I and Christianity|Persecution of paganism under Theodosius I}} |

||

[[File:Ancient Roman Temple, Évora - Apr 2011.jpg|thumb|Ancient_Roman_Temple,_Évora_-_Apr_2011|Ancient Roman Temple Evora. Believed to have been dedicated to the Roman goddess Diana, this 2nd or 3rd century temple survived because it was converted to a number of uses over the centuries -- such as an armory, theater and animal slaughterhouse.]] |

|||

[[File:Constantine's conversion.jpg|thumb|left|''Constantine's conversion'', by [[Peter Paul Rubens|Rubens]].]] |

|||

In Late Antique Roman Empire, sites already consecrated as pagan temples or [[Mithraism|mithraea]] began being converted into Christian churches.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=xxxix}}{{sfn|Markus|1990|p=142}} Scholarship has been divided over whether this was a general effort to demolish the pagan past, simple pragmatism, or perhaps an attempt to preserve the past's art and architecture, or most likely, some combination.{{sfn|Schuddeboom|2017|pp=166-167; 177}} |

|||

[[R. P. C. Hanson]] says the direct conversion of temples into churches began in the mid-fifth century but only in a few isolated incidents.{{sfn|Hanson|1978|p=257}} According to modern archaeology, 120 pagan temples were converted to churches in the whole of the empire, out of the thousands of temples that existed, with the majority of those conversions dated after the fifth century. It is likely this timing stems from the fact that these buildings and sacred places remained officially in public use, ownership could only be transferred by the emperor, and temples remained protected by law.{{sfn|Schuddeboom|2017|p=181-182}} |

|||

Peter Brown has written that, "it would be profoundly misleading" to claim that the cultural and social changes that took place in Late Antiquity reflected "in any way" that the empire had become Christianized.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=652}} Brown asserts "it is impossible to speak of a Christian empire as existing before Justinian" in the sixth century. {{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=652-653}} |

|||

In the fourth century, there were no conversions of temples in the city of Rome itself.{{sfn|Schuddeboom|2017|pp=169}} It is only with the formation of the Papal State in the eighth century, (when the emperor's properties in the West came into the possession of the bishop of Rome), that the conversions of temples in Rome took off in earnest.{{sfn|Schuddeboom|2017|p=179}} |

|||

Instead, the "flowering of a vigorous public culture that polytheists, Jews and Christians alike could share... [that] could be described as Christian "only in the narrowest sense" developed. It is true that Christianity made sure blood sacrifice played no part in that culture, but the sheer success and unusual stability of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian state also ensured that "the edges of potential conflict were blurred... It would be wrong to look for further signs of Christianization at this time".{{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=652-653}} |

|||

According to Dutch historian Feyo L. Schuddeboom, individual temples and temple sites in the city were converted to churches primarily to preserve their exceptional architecture. They were also used pragmatically because of the importance of their location at the center of town.{{sfn|Schuddeboom|2017|pp=181-182}} |

|||

===Favoritism and hostility=== |

|||

The Christianization of the [[Roman Empire]] is frequently divided by scholars into the two phases of before and after the conversion of [[Constantine I (emperor)|Constantine]] in 312.{{sfn|Siecienski|2017|p=3}}{{refn|group=note|There have, historically, been many different scholarly views on Constantine's religious policies.{{sfn|Drake|1995|pp=2, 15}} For example [[Jacob Burckhardt]] has characterized Constantine as being "essentially unreligious" and as using the Church solely to support his power and ambition. Drake asserts that "critical reaction against Burckhardt's anachronistic reading has been decisive."{{sfn|Drake|1995|pp=1, 2}} According to Burckhardt, being Christian automatically meant being intolerant, while Drake says that assumes a uniformity of belief within Christianity that does not exist in the historical record.{{sfn|Drake|1995|p=3}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

Brown calls Constantine's conversion a "very Roman conversion."{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=61}} "He had risen to power in a series of deathly civil wars, destroyed the system of divided empire, believed the Christian God had brought him victory, and therefore regarded that god as the proper recipient of religio".{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=61}} Brown says Constantine was over 40, had most likely been a traditional polytheist, and was a savvy and ruthless politician when he declared himself a Christian.{{sfn|Brown|2012|pp=60-61}} }} According to [[Harold A. Drake]], Constantine's official imperial religious policies did not stem from faith as much as they stemmed from his duty as Emperor to maintain peace in the empire.{{sfn|Siecienski|2017|p=4}} Drake asserts that, since Constantine's reign followed Diocletian's failure to enforce a particular religious view, Constantine was able to observe that coercion had not produced peace.{{sfn|Siecienski|2017|p=4}} |

|||

====Temple and icon destruction==== |

|||

Contemporary scholars are in general agreement that Constantine did not support the suppression of paganism by force.{{sfn|Leithart|2010|p=302}}{{sfn|Wiemer|1994|p=523}}{{sfn|Drake|1995|p=7–9}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|pp=122-126}} He never engaged in a [[purge]],{{sfn|Leithart|2010|p=304}} there were no pagan martyrs during his reign.{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=74}}{{sfn|Thompson|2005|p=87,93}} Pagans remained in important positions at his court.{{sfn|Leithart|2010|p=302}} Constantine ruled for 31 years and never outlawed paganism.{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=74}}{{sfn|Drake|1995|pp=3, 7}} A few authors suggest that "true Christian sentiment" might have motivated Constantine, since he held the conviction that, in the realm of faith, only freedom mattered.{{sfn|Digeser|2000|p=169}}{{refn|group=note|During his long reign, Constantine destroyed a few temples, plundered more, and generally neglected the rest.{{sfn|Wiemer|1994|p=523}} In Eusebius' church history, there is a bold claim of a Constantinian campaign against the temples, however, there are discrepancies in the evidence.{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|p=123}} Temple destruction is attested to in 43 cases in the written sources, but only four have been confirmed by archaeological evidence.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|pp=xxvii; xxiv}} {{paragraph break}} Trombley and MacMullen explain that discrepancies between literary sources and archaeological evidence exist because it is common for details in the literary sources to be ambiguous and unclear.{{sfn|Trombley|1995a|pp=166–168; 335–336}} For example, [[John Malalas|Malalas]] claimed Constantine destroyed all the temples, then he said Theodisius destroyed them all, then he said Constantine converted them all to churches.{{sfn|Trombley|2001|pp=246–282}}{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=110}}{{paragraph break}} At the sacred oak and spring at [[Mamre]], a site venerated and occupied by Jews, Christians, and pagans alike, the literature says Constantine ordered the burning of the idols, the destruction of the altar, and erection of a church on the spot of the temple.{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|p=131}} The archaeology of the site shows that Constantine's church, along with its attendant buildings, only occupied a peripheral sector of the precinct, leaving the rest unhindered.{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=31}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

During his long reign (307 - 337), [[Constantine the Great|Constantine]] (the first Christian emperor) destroyed a few temples, plundered more, and generally neglected the rest.{{sfn|Wiemer|1994|p=523}} Classicist Scott Bradbury says Constantine "confiscated temple funds to help finance his own building projects", and he confiscated temple hoards of gold and silver to establish a stable currency; on a few occasions, he confiscated temple land.{{sfn|Bradbury|1995}} |

|||

A number of elements coincided to end the temples, but none of them were strictly religious.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=82}} Earthquakes caused much of the destruction of this era.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=28}} Civil conflict and external invasions also destroyed many temples and shrines.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=xxvi}} Economics was also a factor.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=82}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1995|p=353}}{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=60}} {{paragraph break}} |

|||

[[File:Constantine's conversion.jpg|thumb|left|''Constantine's conversion'', by [[Peter Paul Rubens|Rubens]].]] |

|||

The Roman economy of the third and fourth centuries struggled, and traditional polytheism was expensive and dependent upon donations from the state and private elites.{{sfn|Jones|1986|pp=8–10;13;735}} Roger S. Bagnall reports that imperial financial support declined markedly after Augustus.{{sfn|Bagnall|2021|pp=261-269}} Lower [[budget]]s meant the physical decline of [[Urban area|urban]] structures of all types. {{paragraph break}} |

|||

In the 300 years prior to the reign of Constantine, Roman authority had confiscated various church properties, some of which were associated with Christian holy places. For example, Christian historians alleged that [[Hadrian]] (2nd century) had, in the military colony of [[Aelia Capitolina]] ([[Jerusalem]]), constructed a temple to [[Aphrodite]] on the site of the [[crucifixion of Jesus]] on [[Calvary|Golgotha]] hill in order to suppress [[Jewish Christian]] veneration there.{{sfn|Loosley|2012|p=3}} Constantine was vigorous in reclaiming such properties whenever these issues were brought to his attention, and he used reclamation to justify the Aphrodite temple's destruction. Using the vocabulary of reclamation, Constantine acquired several more sites of Christian significance in the Holy Land.{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=30}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|p=132}} |

|||

This progressive decay was accompanied by an increased trade in salvaged building materials, as the practice of [[recycling]] became common in Late Antiquity.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=2}} Economic struggles meant that necessity drove much of the destruction and conversion of pagan religious monuments.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=82}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1995|p=353}}{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=60}} In many instances, such as in [[Tripolitania]], this happened before Constantine the Great became emperor.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=29}}{{paragraph break}} Constantine "confiscated temple funds to help finance his own building projects", and he confiscated temple hoards of gold and silver to establish a stable currency; on a few occasions, he confiscated temple land;{{sfn|Bradbury|1995}} he refused to personally support pagan beliefs and practices while also speaking out against them.{{sfn|Boyd|2005|p=16}} He forbade pagan sacrifices and closed temples that continued to offer them;{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=74}} he wrote laws that favored Christianity; he granted to Christians those governmental privileges, such as tax exemptions and the right to hold property, that had previously been available only to pagan priests;{{sfn|Southern|2015|p=455–457}}{{sfn|Gerberding|Moran Cruz|2004|p=55–56}} he personally endowed Christians with gifts of money, land and government positions.{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=243}}{{sfn|Leithart|2010|p=302}} Yet Constantine never stopped the established state support of the traditional religious institutions.{{sfn|Boyd|2005|p=16}} }} |

|||

In Eusebius' church history, there is a bold claim of a Constantinian campaign to destroy the temples, however, there are discrepancies in the evidence.{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|p=123}}{{refn|group=note|A number of elements coincided to end the temples, but none of them were strictly religious.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=82}} Earthquakes caused much of the destruction of this era.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=28}} Civil conflict and external invasions also destroyed many temples and shrines.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=xxvi}} Economics was also a factor.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=82}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1995|p=353}}{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=60}} |

|||

Making the adoption of Christianity beneficial was Constantine's primary approach to religion, and imperial favor was important to successful Christianization over the next century.{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=243}}{{sfn|Southern|2015|p=455–457}} However, Constantine must have written the laws that threatened and menaced pagans who continued to practice sacrifice. There is no evidence of any of the horrific punishments ever being enacted.{{sfn|Digeser|2000|pp=168-169}} There is no record of anyone being executed for violating religious laws before Tiberius II Constantine at the end of the sixth century (574–582).{{sfn|Thompson|2005|p=93}} Still, classicist Scott Bradbury notes that the complete disappearance of public sacrifice by the mid-fourth century "in many towns and cities must be attributed to the atmosphere created by imperial and episcopal hostility".{{sfn|Bradbury|1995|p=345-356}}{{refn|group=note|Constantine did not destroy large numbers of temples, but he did destroy a few. In the previous 300 years, Roman authority had periodically confiscated various church properties, some of which were associated with Christian holy places. For example, Christian historians alleged that [[Hadrian]] (2nd century) had, in the military colony of [[Aelia Capitolina]] ([[Jerusalem]]), constructed a temple to [[Aphrodite]] on the site of the [[crucifixion of Jesus]] on [[Calvary|Golgotha]] hill in order to suppress [[Jewish Christian]] veneration there.{{sfn|Loosley|2012|p=3}} Constantine was vigorous in reclaiming confiscated properties whenever these issues were brought to his attention, and he used reclamation to justify the destruction of Aphrodite's temple in Jerusalem.{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=30}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|p=132}} Using the vocabulary of reclamation, Constantine acquired several more sites of Christian significance in the Holy Land.{{paragraph break}} |

|||

{{paragraph break}} |

|||

The Roman economy of the third and fourth centuries struggled, and traditional polytheism was expensive and dependent upon donations from the state and private elites.{{sfn|Jones|1986|pp=8–10;13;735}} Roger S. Bagnall reports that imperial financial support of the Temples declined markedly after Augustus.{{sfn|Bagnall|2021|pp=261-269}} Lower [[budget]]s meant the physical decline of [[Urban area|urban]] structures of all types. |

|||

{{paragraph break}} |

|||

This progressive decay was accompanied by an increased trade in salvaged building materials, as the practice of [[recycling]] became common in Late Antiquity.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=2}} Economic struggles meant that necessity drove much of the destruction and conversion of pagan religious monuments.{{sfn|Leone|2013|p=82}}{{sfn|Bradbury|1995|p=353}}{{sfn|Brown|2003|p=60}}}} Temple destruction is attested to in 43 cases in the written sources, but only four have been confirmed by archaeological evidence.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|pp=xxvii; xxiv}} Trombley and MacMullen explain that discrepancies between literary sources and archaeological evidence exist because it is common for details in the literary sources to be ambiguous and unclear.{{sfn|Trombley|1995a|pp=166–168; 335–336}} For example, [[John Malalas|Malalas]] claimed Constantine destroyed all the temples, then he said Theodisius destroyed them all, then he said Constantine converted them all to churches.{{sfn|Trombley|2001|pp=246–282}}{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=110}}{{refn|group=note|At the sacred oak and spring at [[Mamre]], a site venerated and occupied by Jews, Christians, and pagans alike, the literature says Constantine ordered the burning of the idols, the destruction of the altar, and erection of a church on the spot of the temple.{{sfn|Bradbury|1994|p=131}} The archaeology of the site shows that Constantine's church, along with its attendant buildings, only occupied a peripheral sector of the precinct, leaving the rest unhindered.{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=31}}{{paragraph break}} In Gaul of the fourth century, 2.4% of known temples and religious sites were destroyed, some by barbarians.{{sfn|Lavan|2011|pp=165-181}} In Africa, the city of Cyrene has good evidence of the burning of several temples; Asia Minor has produced one weak possibility; in Greece the only strong candidate may relate to a barbarian raid instead of Christians. Egypt has produced no archaeologically confirmed temple destructions from this period except the [[Serapeum of Alexandria|Serapeum]]. In Italy there is one; Britain has the highest percentage with 2 out of 40 temples.{{sfn|Lavan|2011|p=xxv}}}} |

|||

The element of pagan culture most abhorrent to Christians was sacrifice, and altars used for it were routinely smashed. Christians were deeply offended by the blood of slaughtered victims as they were reminded of their own past sufferings associated with such altars.{{sfn|Bradbury|1995|pp=331; 346}} |

|||

Calculated acts of desecration – removing the hands and feet of statues of the divine, mutilating heads and genitals, tearing down altars and "purging sacred precincts with fire" – were acts committed by the people during the early centuries. While seen as 'proving' the impotence of the gods, pagan icons were also seen as having been "polluted" by the practice of sacrifice. They were, therefore, in need of "desacralization" or "deconsecration" (a practice not limited to Christians).{{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=649-652}} Brown says that, while it was in some ways studiously vindictive, it was not indiscriminate or extensive.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=650}}{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|pp=39, 40}} Once these objects were detached from 'the contagion' of sacrifice, they were seen as having returned to innocence. Many statues and temples were then preserved as art.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=650}} Professor of Byzantine history Helen Saradi-Mendelovici writes that this process implies appreciation of antique art and a conscious desire to find a way to include it in Christian culture.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=303}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

Additional calculated acts of desecration – removing the hands and feet or mutilating heads and genitals of statues, and "purging sacred precincts with fire" – were acts committed by the common people during the early centuries.{{refn|group=note|There are only a few examples of Christian officials having any involvement in the violent destruction of pagan shrines. [[Sulpicius Severus]], in his ''Vita,'' describes [[Martin of Tours]] as a dedicated destroyer of temples and sacred trees, saying "wherever he destroyed [[heathen temple]]s, there he used immediately to build either churches or monasteries".{{sfn|Severus – Vita}} There is agreement that Martin destroyed temples and shrines, but there is a discrepancy between the written text and archaeology: none of the churches attributed to Martin can be shown to have existed in Gaul in the fourth century.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=178}} {{paragraph break}} |

|||

In the 380s, one eastern official (generally identified as the praetorian prefect [[Maternus Cynegius|Cynegius]]), used the army under his control and bands of [[monk]]s to destroy temples in the eastern provinces.{{sfn|Haas|2002|pp=160–162}} According to [[Alan Cameron (classicist)|Alan Cameron]], this violence was unofficial and without support from Christian clergy or state magistrates.{{sfn|Cameron|2011|p=799}}{{sfn|Salzman|2006|pp=284–285}}}} While seen as 'proving' the impotence of the gods, pagan icons were also seen as having been "polluted" by the practice of sacrifice. They were, therefore, in need of "desacralization" or "deconsecration".{{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=649-652}} Brown says that, while it was in some ways studiously vindictive, it was not indiscriminate or extensive.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=650}}{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|pp=39, 40}} Once temples, icons or statues were detached from 'the contagion' of sacrifice, they were seen as having returned to innocence. Many statues and temples were then preserved as art.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=650}} Professor of Byzantine history Helen Saradi-Mendelovici writes that this process implies appreciation of antique art and a conscious desire to find a way to include it in Christian culture.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=303}} |

|||

Paganism did not end when public sacrifice did.{{sfn|Constantelos|1964|p=372}}{{sfn|Brown|1998|pp=641; 645}} Brown explains that polytheists were accustomed to offering prayers to the gods in many ways and places that did not include sacrifice, that pollution was only associated with sacrifice, and that the ban on sacrifice had fixed boundaries and limits.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=645}} Paganism thus remained widespread into the early fifth century continuing in parts of the empire into the seventh and beyond.{{sfn|Salzman|2002|p=182}} |

|||

=== |

====Other sacred sites==== |

||

[[File:Spoleto SSalvatore Presbiterio1.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Physical Christianization: the choir of San Salvatore, [[Spoleto]], occupies the [[cella]] of a Roman temple.]] |

|||

{{See also|Interpretatio Christiana}} |

|||

Christianizing native religious and cultural activities and beliefs became official in the sixth century. This argument (in favor of what in modern terms is syncretism), is preserved in the [[Bede|Venerable Bede]]'s ''[[Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum]]'' in the form of a letter from Pope Gregory to [[Mellitus]] (d.604).{{sfn|Bede|2007|p=53}} L. C. Jane has translated Bede's text: <blockquote>Tell Augustine that he should by no means destroy the temples of the gods but rather the idols within those temples. Let him, after he has purified them with holy water, place altars and relics of the saints in them. For, if those temples are well built, they should be converted from the worship of demons to the service of the true God. Thus, seeing that their places of worship are not destroyed, the people will banish error from their hearts and come to places familiar and dear to them in acknowledgement and worship of the true God. [[Bede]], [[Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum]] (1.30)</blockquote> |

|||

<blockquote>Late Antiquity from the third to the sixth centuries was the era of the development of the great Christian narrative, an ''interpretatio Christiana'' of the history of humankind. In this reconstruction of the past, Christian writers built on preceding tradition, creating competing chronologies and alternative histories.{{sfn|Kahlos|2015|p=12}}</blockquote> In the early fourth century, Eusebius wrote ''Chronici canones''. In it, he developed an elaborate synchronistic chronology reinterpreting the Greco-Roman past to reflect a Christian perspective.{{sfn|Kahlos|2015|pp=11; 28}} |

|||

[[File:GraoullyAugusteMigette.jpg|thumb|left|Representation of [[Clement of Metz|Saint Clement]] fighting the Graoully dragon in the Roman amphitheater of [[Metz]]. Christian hagiography presents bishops as pious and powerful, defeating demons posing as pagan gods.{{sfn|Brown|1993|pp=90–91; 640}} ]] |

|||

When [[Benedict of Nursia|Benedict]] moved to [[Monte Cassino]] about 530, a small temple with a sacred grove and a separate altar to Apollo stood on the hill. The population was still mostly pagan. The land was most likely granted as a gift to Benedict from one of his supporters. This would explain the authoritative way he immediately cut down the groves, removed the altar, and built an oratory before the locals were converted.{{sfn|Farmer|1995|p=26}} |

|||

Orosius wrote ''Historiae adversus paganos'' in the early fifth century in response to the charge that the Roman Empire was in misery and ruins because it had converted to Christianity and neglected the old gods.{{sfn|Kahlos|2015|p=28}} [[Maijastina Kahlos]] explains that, "In order to refute these claims, Orosius reviewed the entire history of Rome, demonstrating that the alleged glorious past of the Romans in fact consisted of war, despair and suffering".{{sfn|Kahlos|2015|p=28}} |

|||

Christianization of the Irish landscape was a complex process that varied considerably depending on local conditions.{{sfn|Harney|2017|p=104}} Ancient sites were viewed with veneration, and were excluded or included for Christian use based largely on diverse local feeling about their nature, character, ethos and even location.{{sfn|Harney|2017|p=120,121}} |

|||

====Theodosius I and orthodoxy==== |

|||

{{Main|Theodosius I}} |

|||

[[File:Diffusion of ideas.svg|upright=1|thumb|Theoretical graph of growth of Christianity in first five centuries of Roman empire|alt=this is a graph showing the normal distribution of a population as how the diffusion of ideas most likely took place]] |

|||

Theodosius I gained a reputation as the emperor who crushed paganism in order to establish Nicene Christianity as the one official religion of the empire in the centuries following his death. Modern historians no longer see this as actual history, but instead, see it as a later interpretation of history – a rewriting of history – by Christian writers.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|p=3}} Cameron explains that, since Theodosius's predecessors [[Constantine I|Constantine]], [[Constantius II|Constantius]], and [[Valens]] had all been [[semi-Arian]]s, it fell to the orthodox Theodosius to receive from Christian literary tradition most of the credit for the final triumph of Christianity.{{sfn|Cameron|1993|p=74 (note 177)}} {{refn|group=note| Numerous literary sources, both Christian and pagan, falsely attributed to Theodosius multiple anti-pagan initiatives such as the withdrawal of state funding to pagan cults (this measure belongs to [[Gratian]]) and the demolition of temples (for which there is no primary evidence).{{sfn|Cameron|1993|pp=46–47, 72}} |

|||

{{paragraph break}}Theodosius was also associated with the ending of the Vestal virgins, but twenty-first century scholarship asserts the Virgins continued until 415 and suffered no more under Theodosius than they had since Gratian restricted their finances.{{sfn|Testa|2007|p=260}} |

|||

{{paragraph break}}Theodosius did turn pagan holidays into workdays, but the festivals associated with them continued.{{sfn|Graf|pp=229–232}} |

|||

{{paragraph break}}Theodosius was associated with ending the [[ancient Olympic Games]], which he also probably did not do.{{sfn|Perrottet|2004|pp=[https://archive.org/details/nakedolympicstru00perr/page/190 190]–}}{{sfn|Hamlet|2004|pp=53–75}} {{ill|Sofie Remijsen|nl}} says there are several reasons to conclude the Olympic games continued after Theodosius I, and that they came to an end under [[Theodosius II|Theodosius the second]], by accident, instead. Two extant scholia on Lucian connect the end of the games with a fire that burned down the temple of the [[Temple of Olympian Zeus, Athens|Olympian Zeus]] during Theodosius the second's reign.{{sfn|Remijsen|2015|p=49}} }} |

|||

In Greece of the sixth century, the [[Parthenon]], the [[Erechtheion]], and the [[Theseion]] were turned into churches, but Alison Frantz has won consensus support of her view that, aside from a few rare instances, temple conversions took place in and after the seventh century, after the displacements caused by the Slavic invasions.{{sfn|Gregory|1986|p=233}} |

|||

Nearly all the sources available on Theodosius are ecclesiastical histories that are highly colored and carefully curated for public reading.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|p=3}} Beginning with contemporaries like the bishop [[Ambrose]], and followed in the next century by church historians such as [[Theodoret]], these histories focus on Theodosius' impact on the church as uniformly positive, orthodox and anti-pagan, frequently going beyond admiration into [[panegyric]] and [[hagiography]].{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|p=3-5}} |

|||

In early Anglo-Saxon England, non-stop religious development meant paganism and Christianity were never completely separate.{{sfn|Wood|2007|p=34}} Lorcan Harney has reported that Anglo-Saxon churches were built by pagan barrows after the 11th century.{{sfn|Harney|2017|p=107}} [[Richard A. Fletcher]] suggests that, within the British Isles and other areas of northern Europe that were formerly [[druid]]ic, there are a dense number of [[holy]] wells and holy springs that are now attributed to a [[saint]], often a highly local saint, unknown elsewhere.{{sfn|Fletcher|1999|p=254}}{{sfn|Weston|1942|p=26}} In earlier times many of these were seen as guarded by supernatural forces such as the [[melusina]], and many such pre-Christian holy wells appear to have survived as baptistries.{{sfn|Harney|2017|pp=119-121}} |

|||

Theodosius did champion Christian orthodoxy, and the majority of the laws he wrote were intended to eliminate heresies and promote unity within Christianity. Scholars say there is little, if any, evidence that Theodosius I ever pursued an active policy against the traditional cults.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|loc=chapter 8; 82}} |

|||

By 771, Charlemagne had inherited the three-century long conflict with the Saxons who regularly specifically targeted churches and monasteries in brutal raids into Frankish territory.{{sfn|Dean|2015|pp=15-16}} In January 772, Charlemagne retaliated with an attack on the Saxon's most important holy site, a [[sacred groves|sacred grove]] in southern Engria.{{sfn|Dean|2015|p=16}} "It was dominated by the [[Irminsul]] ('Great Pillar'), which was either a (wooden) pillar or an ancient tree and presumably symbolized Germanic religion's 'Universal Tree'. The Franks cut down the Irminsul, looted the accumulated sacrificial treasures (which the King distributed among his men), and torched the entire grove... Charlemagne ordered a Frankish fortress to be erected at the Eresburg".{{sfn|Dean|2015|pp=16-17}} |

|||

In 380, he issued the [[Edict of Thessalonica]] to the people of Constantinople. It was addressed to Arian Christians, granted Christians no favors or advantages over other religions, and it is clear from mandates issued in the years after 380, that Theodosius had not intended it as a requirement for pagans or Jews to convert to Christianity.{{sfn|Sáry|2019|pp=72-74; 77}} Hungarian legal scholar Pál Sáry explains that, "In 393, the emperor was gravely disturbed that the Jewish assemblies had been forbidden in certain places. For this reason, he stated with emphasis that the sect of the Jews was forbidden by no law".{{sfn|Sáry|2019|pp=72-74; fn. 32, 33, 34; 77}}{{refn|group=note|The Edict of Thessalonica declared those Christians who refused the Nicene faith to be ''infames'', and prohibited them from using Christian churches.{{sfn|Sáry|2019|pp=73, 77}} Sáry uses this example: "After his arrival in Constantinople, Theodosius offered to confirm the Arian bishop Demophilus in his see, if he would accept the Nicene Creed. After Demophilus refused the offer, the emperor immediately directed him to surrender all his churches to the Catholics."{{sfn|Sáry|2019|p=79}}}} |

|||

Early historians of Scandinavian Christianization wrote of dramatic events associated with Christianization in the manner of political propagandists according to {{ill|John Kousgärd Sørensen|Da}} who references the 1987 survey by Birgit Sawyer.<ref name="Sørensen 1990">Kousgård Sørensen, J. (1990). The change of religion and the names. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis, 13, 394–403. https://doi.org/10.30674/scripta.67188</ref>{{rp|p=394}} Sørensen focuses on the changes of names, both personal and place names, showing that cultic elements were not banned from personal names and are still in evidence today.<ref name="Sørensen 1990"/>{{rp|pp=395-397}} Considering place names, large numbers of pre-Christian names survive into the present day demonstrating missionaries had the sense that eradicating elements of the old religion was not necessary.<ref name="Sørensen 1990"/>{{rp|p=400}} Indications are that the process of Christianization in Denmark was peaceful and gradual and did not include the complete eradication of the old cultic associations. However, there are local differences as well.<ref name="Sørensen 1990"/>{{rp|p=400, 402}} |

|||

It has long been an accepted axiom that a universal ban on paganism, and the establishment of Christianity as the singular religion of the empire, can be implied from Theodosius' later laws such as that issued in November 392.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|loc=chapter 8; 82}}{{sfn|Errington|2006|loc=chapter 8; 248–249, 251}}{{sfn|Errington|1997|pp=410–415}}{{refn|group=note| The English translation reads: "16.10.12 (8th November 392): Emperors Theodosius, Arcadius and Honorius to Rufinus, praetorian prefect: nobody, of whatsoever condition and class, who was appointed for an office or some privilege, should he be powerful for his origin or born in humble conditions, absolutely nowhere, in no city, shall offer an innocent victim to the meaningless idols, nor, as a worse sacrilege, worship the Lares with fire, the Genius with wine, the Penates with perfumes, nor shall light lamps or put incense after them, nor hang wreaths. If someone dares to sacrifice a victim or consult its still warm intrails, he'll be charged for high treason and subject to the prescribed penalty, even though he didn't try to divine anything in favour or against the prince's health. For the crime to be grave it's enough the will of going against the laws of nature, to investigate illicit things, to discover the hidden, to try the forbidden, to want to put an end to everyone else's health, to hope in someone's death. If someone adores, by putting incense after them, images made by human hands and therefore suffering the passing of time, or suddenly fears in a ridicule manner what himself made, or, after putting ribbons on a tree or constructing an altar out of clumps, tries to honor the vane idols with an even modest gift, but completely despising religion, he will be charged of religion violation and will be punished with confiscation of the house or land in which the superstition of gentiles will be proven to have survived. Therefore, all places in which will be proven that the smoke of incense raised, if they're property of the person who burnt the incense, will be attributed to the imperial revenue. If the guilty tries some form of sacrifice in a public temple or sanctuary or in a place belonging to another person and if this latter is recognized unaware of what happened, the guilty will pay 25 pounds of gold and the same amount will be paid by every accomplice. We wish judges, defender and curial officers in every city to implement what we said, so that on one hand they refer violations to the court, on the other they punish the referred facts. But if they conceal something for benevolence or let it unpunished for negligence, they'll underwent the trial; if they have been warned of the crime but omitted to implement the provided punishment, they would pay a fine of 30 pounds and so their staff."<ref>{{cite web |last1=Simioni |first1=Manuela |title=THEODOSIAN CODE (CODEX THEODOSIANUS) 16.10: TEXT |url=http://www.giornopaganomemoria.it/theodosian1610.html# |website=European Pagan Memory Day |access-date=14 February 2023}}</ref>}} This law was only sent to Rufinus in the East;{{sfn|Cameron|2011|pp=61}} it describes and bans all types of private domestic sacrifice, which were thought to have "slipped out from under public control";{{sfn|Bilias |Grigolo|2019|p=82}} it bans magic used for divining the future from such sacrifices, and any idolatry associated with those sacrifices.{{sfn|Kahlos|2019|p=146}} It makes no mention of Christianity at all.{{sfn|Roux|2018}}{{sfn|Simeoni|n.d.}} [[Sozomen]], the Constantinopolitan lawyer, wrote a history of the church around 443 where he evaluates the law of 392 as having had only minor significance at the time it was issued.{{sfn|Errington|1997|p=431}}{{sfn|Cameron|2011|pp=60, 63, 68}}{{refn|group=note|The Theodosian Law Code has long been one of the principal historical sources for the study of Late Antiquity.{{sfn|Lepelley|1992|pp=50–76}} Gibbon described the Theodosian decrees, in his ''Memoires'', as a work of history rather than jurisprudence.{{sfn|Quinault|McKitterick|2002|p=25}} Brown says the language of these laws is uniformly vehement, and penalties are harsh and frequently horrifying, leading some historians, such as [[Ramsay MacMullen]], to see them as a 'declaration of war' on traditional religious practices.{{sfn|MacMullen|1981|p=100}}{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=638}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

It has been a common axiom among historians that the laws marked a turning point in the decline of paganism.{{sfn|Trombley|2001|p=12}} Yet, many contemporary scholars such as Lepelley, Brown and Cameron, and others question using a legal document as a record of history.{{sfn|Lepelley|1992|pp=50–76}} They say no legal code has the ability to tell how, or if, its policies were actually carried out.{{sfn|Stachura|2018|p=246}}{{sfn|Salzman|1993|p=378}} There is no record of anyone in Constantine's era being executed for sacrificing, nor is there evidence of any of the horrific punishments ever being enacted.{{sfn|Digeser|2000|pp=168–169}}{{sfn|Thompson|2005|p=93}} Archaeologists Luke Lavan and Michael Mulryan have written that the Code can be seen to document "Christian ambition" but not historic reality.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=xxii}}{{sfn|Lepelley|1992|pp=50–76}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

The overtly violent fourth century that one would expect to find from taking the laws at face value is simply not supported by archaeological evidence from around the Mediterranean.{{sfn|Mulryan|2011|p=41}}{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|pp=xxi, 138}}{{sfn|Errington|1997|p=398}} Cameron concludes there is no solid evidence for a universal ban on paganism in the Roman empire.{{sfn|Cameron|2011|pp=61; 99}}}} |

|||

Outside of Scandinavia, old names did not fare as well.<ref name="Sørensen 1990"/>{{rp|pp=400-401}} <blockquote>The highest point in Paris was known in the pre-Christian period as the Hill of Mercury, Mons Mercuri. Evidence of the worship of this Roman god here was removed in the early Christian period and in the ninth century a sanctuary was built here, dedicated to the 10000 martyrs. The hill was then called Mons Martyrum, the name by which it is still known (Mont Martres) (Longnon 1923, 377; Vincent 1937, 307). San Marino in northern Italy, the shrine of Saint Marino, replaced a pre-Christian cultic name for the place: Monte Titano, where the Titans had been worshipped (Pfeiffer 1980, 79). [The] Monte Giove "Hill of Jupiter" came to be known as San Bernardo, in honour of St Bernhard (Pfeiffer 1980, 79). In Germany an old Wodanesberg "Hill of Ódin" was renamed Godesberg (Bach 1956, 553). Ä controversial but not unreasonable suggestion is that the locality named by Ädam of Bremen as Fosetisland "land of the god Foseti" is to be identified with Helgoland "the holy land", the island off the coast of northern Friesland which, according to Ädam, was treated with superstitious respect by all sailors, particularly pirates (Laur 1960, 360 with refer- ences), <ref name="Sørensen 1990"/>{{rp|p=401}}</blockquote> |

|||

During the reign of Theodosius, pagans were continuously appointed to prominent positions and pagan aristocrats remained in high offices.{{sfn|Sáry|2019|p=73}} Theodosius allowed pagan practices that did not involve sacrifice to be performed publicly and temples to remain open.{{sfn|Kahlos|2019|p=35 (and note 45)}}{{sfn|Errington|2006|pp=245, 251}}{{sfn|Woods|loc=Religious Policy}}{{refn|group=note|During his first official tour of Italy (389–391), the emperor won over the influential pagan lobby in the Roman Senate by appointing its foremost members to important administrative posts.{{sfn|Cameron|2011|pp=56, 64}} Theodosius also nominated the last pair of pagan consuls in Roman history ([[Eutolmius Tatianus|Tatianus]] and [[Quintus Aurelius Symmachus Eusebius|Symmachus]]) in 391.{{sfn|Bagnall et al|1987|p=317}}{{paragraph break}} He also voiced his support for the preservation of temple buildings, but nonetheless failed to prevent the damaging of several holy sites in the eastern provinces.{{sfn|Woods|loc=Religious Policy}}{{sfn|Errington|2006|p=249}}{{sfn|MacMullen|1984|p=90}} {{paragraph break}} |

|||

Following the death in 388 of [[Maternus Cynegius|Cynegius]], the praetorian prefect thought to be responsible for that vandalization, Theodosius replaced him with a moderate pagan who subsequently moved to protect the temples.{{sfn|Trombley|2001|p=53}}{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|loc=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Cameron|2011|p=57}} {{paragraph break}} There is no evidence of any desire on the part of the emperor to institute a systematic destruction of temples anywhere in the Theodosian Code, and no evidence in the archaeological record that extensive temple destruction took place.{{sfn|Lavan|Mulryan|2011|p=xxx}}{{sfn|Fowden|1978|p=63}} According to Bayliss, "There is no single law of the Theodosian Code containing a specific order for the destruction of temples that does not include the pretext of sacrifice or idolatry. Even Theodosius' law of 435, seen by most scholars as the ''coup de grace'' of surviving temples only applies to the temples of pagans who had committed illegal acts of sacrifice. It is quite possible that the significance of this law has been overemphasized by scholars".{{sfn|Bayliss|2004|p=41}} }} In his 2020 biography of Theodosius, Mark Hebblewhite concludes that Theodosius never saw himself, or advertised himself, as a destroyer of the old cults. The emperor's efforts at Christianization were "targeted, tactical, and nuanced".{{sfn|Hebblewhite|2020|loc=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Errington|2006|p=251}}{{sfn|Cameron|2011|p=71}} |

|||

The practice of replacing pagan beliefs and motifs with Christian, and purposefully not recording the pagan history (such as the names of pagan gods, or details of pagan religious practices), has been compared to the practice of ''[[damnatio memoriae]]''.{{sfn|Strzelczyk|1987|p=60}} |

|||

===Method=== |

|||

According to H. A. Drake, Christians worried about the validity of coerced faith and resisted such aggressive actions for centuries.{{sfn|Drake|2011|p=196}} Tertullian held that 'the free exercise of religious choice was a tenet of both man made and natural law', and that religion was 'something to be taken up voluntarily, not under duress".{{sfn|Drake|1996|p=10}} In Peter Garnsey's view, "Christians were the only group in antiquity to enunciate conditions for practicing religious toleration as a principle, rather than as an expedient".{{sfn|Drake|1996|p=10}} |

|||

===Conversion of nations=== |

|||

In the fourth century, a council of Spanish Bishops meeting in [[Elvira]] on the coast of Spain, determined that Christians who died in attacks on idol temples should not be received as martyrs. The bishops wrote that they took this stand of disapproval because "such actions cannot be found in the Gospels, nor were they ever undertaken by the Apostles".{{sfn|Drake|2011|p=203}} |

|||

{{Main|Early Christianity|Acts of the Apostles|Historiography of the Christianization of the Roman Empire|Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation}} |

|||

{{See also|Early centers of Christianity#Rome}} |

|||

Drake suggests this stands as testimony to the tradition established in early Christianity which favored and operated toward peace, moderation, and conciliation. "It was a tradition that held true belief could not be compelled for the simple reason that God could tell the difference between voluntary and coerced worship".{{sfn|Drake|2011|p=203}} Peter Brown has written that, <blockquote>It would be a full two centuries before Justinian would envisage the compulsory baptism of remaining polytheists, and a further century until Heraclius and the Visigothic kings of Spain would attempt to baptize the Jews. In the fourth century, such ambitious schemes were impossible.{{sfn|Brown|1998|p=640}}</blockquote> |

|||

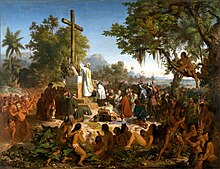

Dana L. Robert has written that Christianization across multiple cultures, societies and nations is understandable only through the concept of ''mission''.<ref name="Robert 2009"/>{{rp|p=1}} Missions, as the embodiment of the Great Commission, are driven by a universalist logic, cannot be equated with western colonialism, but are instead a multi-cultural often complex historical process.<ref name="Robert 2009"/>{{rp|p=1}} |

|||

====Roman Empire==== |

|||

There is no evidence to indicate that conversion of pagans through force was an accepted method of Christianization at any point in Late Antiquity; all uses of imperial force concerning religion were aimed at Christian heretics such as the [[Donatism|Donatists]] and the [[Manichaeism|Manichaeans]].{{sfn|Salzman|2006|pp=268–269}}{{sfn|Marcos|2013|pp=1–16}}{{refn|group=note|In his 1984 book, ''Christianizing the Roman Empire: (A.D. 100–400)'', and again in 1997, [[Ramsay MacMullen]] argues that widespread Christian anti–pagan violence, as well as persecution from a "bloodthirsty" and violent Constantine (and his successors), caused the Christianization of the Roman Empire in the fourth century.{{sfn|MacMullen|1984|p=46–50}}{{sfn|Salzman|2006|p=265}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

=====Christianization without coercion===== |

|||

Award winning historian Michelle Renee Salzman describes MacMullen's book as "controversial".{{sfn|Salzman|2006|p=265}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||

There is agreement among twenty-first century scholars that Christianization of the Roman Empire in its first three centuries did not happen by imposition.{{sfn|Runciman|2004|p=6}} Christianization emerged naturally as the cumulative result of multiple individual decisions and behaviors.{{sfn|Collar|2013|p=6}} |

|||

In a review, T. D. Barnes has written that MacMullen's book treats "non-Christian evidence as better and more reliable than Christian evidence", generalizes from pagan polemics as if they were unchallenged fact, misses important facts entirely, and shows an important selectivity in his choices of what ancient and modern works he discusses.{{sfn|Barnes|1985|p=496}}{{paragraph break}} |

|||