Kambojas: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1144962530 by HistoryofIran (talk) Undone due to disruptive editing and leading towards vandalism. User provides no reason as to the rermoval of this text whilst I have previously stated the reasoning for keeping it as he doesnt provide a neutra point of view hence it as been undone. |

m Normalize {{Multiple issues}}: Merge 1 template into {{Multiple issues}}: Under construction |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Short description|Ancient Indian Kingdom}} |

{{Short description|Ancient Indian Kingdom}} |

||

{{Multiple issues| |

{{Multiple issues| |

||

| Line 5: | Line 4: | ||

{{cite check|date=September 2009}} |

{{cite check|date=September 2009}} |

||

{{synthesis|date=November 2009}} |

{{synthesis|date=November 2009}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

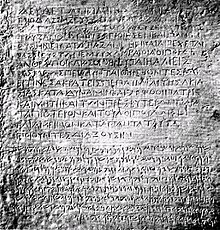

[[Image:AsokaKandahar.jpg|thumb|The [[Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription]], in which the Kambojas are mentioned]] |

[[Image:AsokaKandahar.jpg|thumb|The [[Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription]], in which the Kambojas are mentioned]] |

||

Revision as of 06:12, 17 March 2023

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The Kambojas were a southeastern Iranian people[a] who inhabited the northeastern most part of the territory populated by Iranian tribes, which bordered the Indian lands. They only appear in Indo-Aryan inscriptions and literature, being first attested during the later part of the Vedic period.[1]

They spoke a language similar to Younger Avestan, whose words are considered to have been incorporated in the Aramao-Iranian version of the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription erected by the Maurya emperor Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE).[1][2] They were adherents of Zoroastrianism, as demonstrated by their beliefs that insects, snakes, worms, frogs, and other small animals had to be killed, a practice mentioned in the Avestan Vendidad.[1]

Name

Kamboja- (later form Kāmboja-) was the name of their territory and identical to the Old Iranian name of *Kambauǰa-, whose meaning is uncertain. A long-standing theory is the one proposed by J. Charpentier in 1923, in which he suggests that the name is connected to the name of Cambyses I and Cambyses II (Kambū̌jiya or Kambauj in Old Persian), both kings from the Achaemenid dynasty. The theory has been discussed several times, but the issues that it posed were never persuadingly resolved.[1]

In the same year, S. Lévi proposed that the name is of Austroasiatic origin, though this is typically rejected.[1]

Geography

The historical boundaries detailing the confederation of the Kambojas is varied. All scholarly and literary accounts encompass a large area at a crossroads between South Asia, Central Asia and West Asia.

D. C. Sircar supposed the Kambojas to have lived in various settlements in the wide area lying between Punjab, Iran, to the south of Balkh.[3]The Mahabharata locates the Kambojas on the near side of the Hindu Kush as neighbors to the Daradas and according to Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri their capital was located at Rajapura in modern day Jammu.[4]

According to R.S. Sharma the Parama Kamboja Kingdom was "located in Central Asia in the Pamir area which largely covered modern Tajikistan. In Tajikistan, the remains of a horse, chariots and spoked wheels, cremation, and Svastika, which are associated with the Indo-aryan speakers dating to between 1500 and 1000 BC, have been found." [5]

History

Reputation

The Kambojas were famous in ancient times for their excellent breed of horses and as remarkable horsemen. According to the Mahāvastu(ii, 185), it states that 'The superb horses of the Kambojas are praised' and according to the 'Sumangala-vilasena'(vol 1, p. 124) the Kambojas were described as the 'home of the horses'.[6]

According to Etienne Lamotte: "Furthermore, Kamboja is regularly mentioned as the "homeland of horses" (asvanam oyatanam), and it was this well-established reputation which possibly earned the horse-breeders of Bajaur and Swat the epithet of Aspasioi (from Old Persian aspa) and Assakenoi (from Sanskrit aśva "horse")."[7] Acording to Arrian(IV.24.6–25, 4), the Aśvaka followed a scorched Earth policy and describes an event during Alexander the Greats invasion where the inhabitants of a city named Arigaeum burnt it down following Alexanders advance and fled.[8] Quintus Curtius Rufus(VIII.10.23–9) vivdly describes the moment Alexander the Great was wounded in the calf by an Assacani arrow during a scouting operation of the city of Masaga.[9] When the battle of Masaga commenced, the Assacani gained a reputation for their women fighting side by side with their husbands in what was a last stand for survival.[10]

When many were thus wounded and not a few killed, the women, taking the arms of the fallen, fought side by side with the men for the imminence of the danger and the great interests at stake forced them to do violence to their nature, and to take an active part in the defence.

— Diodorus (XVII.84.1), History of civilisations of Central Asia, Vol II, p. 75

Mauryan empire

According to the Mudrarakshasa when Chandragupta Maurya made his alliance with the Trigarta king, Parvatek, his military composed of men from the Kamboja republic among others which are mentioned in the list.[11][12] Rock Edict XIII of Ashoka tells us that the Kambojas had enjoyed autonomy under the Mauryas,[13][14] and according to Paul J. Kosmin the Kambojas and Ghandharans represented the Western border of the empire.[15]The republics mentioned in Rock Edict V are the Yonas, Kambojas, Gandharas, Nabhakas and the Nabhapamkitas, they are designated as araja vishaya in Rock Edict XIII, which means that they were kingless, republican polities that formed a self-governing political unit under the Maurya emperors.[16][17]Ashoka sent missionaries to the Kambojas to convert them to Buddhism, and recorded this fact in his Rock Edict V.[18][19]

Invasion into India

During the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, clans of the Kambojas from Central Asia in alliance with the Sakas, Pahlavas and the Yavanas entered present-day India, spreading into Sindhu, Saurashtra, Malwa, Rajasthan, Punjab and Surasena, and set up independent principalities in western and south-western India. Later, a branch of the same people took Gauda and Varendra territories from the Palas and established the Kamboja-Pala Dynasty of Bengal in Eastern India.[20][21][22]

There are references to the hordes of the Sakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, and Pahlavas in the Bala Kanda of the Valmiki Ramayana. In these verses one may see glimpses of the struggles of the Hindus with the invading hordes from the north-west.[13][23][24] The royal family of the Kamuias mentioned in the Mathura Lion Capital are believed to be linked to the royal house of Taxila in Gandhara.[25] In the medieval era, the Kambojas are known to have seized north-west Bengal (Gauda and Radha) from the Palas of Bengal and established their own Kamboja-Pala Dynasty. Indian texts like Markandeya Purana, Vishnu Dharmottari Agni Purana,[26]

Kamboja-Pala dynasty

According to renowned historian Abdul Momin Chowdhury, the expanionist movements of Yashodharman may have led to the downfall of the Pala Empire and the rise of Kamboja dominence in Bengal, eventually leading to the Kambojas carving out a state for themselves between the 10th and 11th century.[27]The evidence given by him supporting the existence of this dynasty were from the Dinajpur pillar inscription ''which formerly stood in the palace of the Maharaja of Dinajpur and records the erection of a Siva temple by a King belonging to the Kamboja family'' and the Irda pillar inscription stating 'Kamboja-vamas-Tilaka' defined as 'the mother of the Maharaja belonging to the Kamboja family'.[28]

The question of how the Kambojas entered into the region has been subject of controversy, Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri has presumed that these Kambojas may have entered into Bengal through the conquests of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty whilst R. C. Majumdar has suggested that ''they were simply officials in the Pala Empire who had taken advantage of internal weakness'' leading to them usurping control.[29]

See also

Notes

- ^ Scholarship agree that the Kambojas were Iranian.[30] Richard N. Frye stated that "Their location and the meaning of the word Kamboja are much debated, but it is at least agreed that they were Iranians living to the northwest of the subcontinent."[31]

References

- ^ a b c d e Schmitt 2021.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 136.

- ^ Sircar, D. C. (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. p. 100. ISBN 9788120806900.

- ^ Bimala Charan Law. Some Ksatriya Tribes Of Ancient India. BRAOU, Digital Library Of India. University Of Calcutta. p. 236.

- ^ Sharma, R. S. (2006-09-18). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908786-0.

- ^ "Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahabharata: Upayana Parva". INDIAN CULTURE. p. 36. Retrieved 2023-03-15.

- ^ Madhava Basak. History Of Indian Buddhism Etienne Lamotte. p. 100.

- ^ "PDF.js viewer" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. p. 23. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ "PDF.js viewer" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. p. 74. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ "PDF.js viewer" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. p. 75. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Kumar, Raj (2008). History Of The Chamar Dynasty : (From 6Th Century A.D. To 12Th Century A.D.). Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7835-635-8.

- ^ Thakur, Molu Ram (1997). Myths, Rituals, and Beliefs in Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-071-2.

- ^ a b "Political History of Ancient India", H. C. Raychaudhuri, B. N. Mukerjee, University of Calcutta, 1996.

- ^ H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee; Asoka and His Inscriptions, 3d Ed, 1968, p 149, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa.

- ^ Kosmin, Paul J. (2014-06-23). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- ^ Hindu Polity, A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, 1978, p 117-121, K. P. Jayswal; Ancient India, 2003, pp 839-40, V. D. Mahajan; Northern India, p 42, Mehta Vasisitha Dev Mohan etc

- ^ Bimbisāra to Aśoka: With an Appendix on the Later Mauryas, 1977, p 123, Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya.

- ^ The North-west India of the Second Century B.C., 1974, p 40, Mehta Vasishtha Dev Mohan - India; Tribes in Ancient India, 1973, p 7

- ^ Yar-Shater 1983, p. 951

- ^ Geographical Data in the Early Purāṇas: A Critical Study, 1972, p 168, M. R. Singh - India.

- ^ History of Ceylon, 1959, p 91, Ceylon University, University of Ceylon, Peradeniya, Hem Chandra Ray, K. M. De Silva.

- ^ Pande (R.) 1984, p. 93

- ^ Shrava 1981, p. 12

- ^ Rishi, 1982, p. 100

- ^ See: Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol II, Part I, p xxxvi; see also p 36, Sten Konow; Indian Culture, 1934, p 193, Indian Research Institute; Cf: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1990, p 142, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland - Middle East.

- ^ Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 127

- ^ Caudhurī, Ābadula Mamina (1967). Dynastic History of Bengal, C. 750-1200 A.D. Asiatic Society of Pakistan. p. 104.

- ^ Caudhurī, Ābadula Mamina (1967). Dynastic History of Bengal, C. 750-1200 A.D. Asiatic Society of Pakistan. pp. 108, 109.

- ^ Caudhurī, Ābadula Mamina (1967). Dynastic History of Bengal, C. 750-1200 A.D. Asiatic Society of Pakistan. p. 113.

- ^ Schmitt 2021; Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 129; Scott 1990, p. 45; Kubica 2023, p. 88; Emmerick 1983, p. 951; Fussman 1987, pp. 779–785; Eggermont 1966, p. 293.

- ^ Frye 1984, p. 154.

Bibliography

- Boyce, Mary; Grenet, Frantz (1991). Beck, Roger (ed.). A History of Zoroastrianism, Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman Rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004293915.

- Eggermont, P.H.L. (1966). The Murundas and the Ancient Trade-Route From Taxila To Ujjain. Brill. pp. 257–296. doi:10.1163/156852066X00119.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Emmerick, R. E. (1983). "Buddhism among Iranians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(2): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 949–964. ISBN 0-521-24693-8.

- Kubica, Olga (2023). Greco-Buddhist Relations in the Hellenistic Far East: Sources and Contexts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1032193007.

- Fussman, G. (1987). "Aśoka ii. Aśoka and Iran". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume II/7:ʿArūż–Aśoka IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 779–785. ISBN 978-0-71009-107-9.

- Frye, R. N. (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3406093975.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2021). "Kamboja". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Scott, David Alan (1990). "The Iranian Face of Buddhism". East and West. 40 (1): 43–77. JSTOR 29756924. (registration required)