Denial of the virgin birth of Jesus

Denial of the virgin birth of Jesus is found among various groups and individuals throughout the history of Christianity. These groups and individuals often took an approach to Christology that understands Jesus to be human, the literal son of human parents.[2][3]

In the 19th century, the view was sometimes called psilanthropism, a term that derives from the combination of the Greek ψιλός (psilós), "plain", "mere" or "bare", and ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos) "human". Psilanthropists then generally denied both the virgin birth of Jesus and his divinity. Denial of the virgin birth is distinct from adoptionism and may or may not be present in beliefs described as adoptionist.

Early Christianity

The group most closely associated with denial of the virgin birth were the Ebionites. However, Jerome does not say that all Ebionites denied the virgin birth, but only contrasts their view with the acceptance of the doctrine on the part of a related group, the Nazarenes.[4][5]

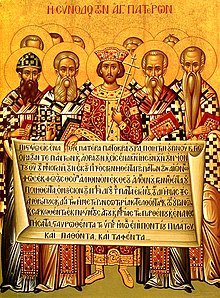

The view was rejected by the ecumenical councils, especially in the First Council of Nicaea, which was convened to deal directly with the nature of Christ's divinity.[6]

Pagan and Jewish accounts

In the 2nd century, the Greek philosopher Celsus claimed that Jesus was the illegitimate son of a soldier named Panthera. The same claim is made by the medieval Jewish text Toledot Yeshu.[7]

Reformation

The turmoil of the Reformation gave rise to many radical groups and individuals, some of whom were accused of denying, or actually did deny, the virgin birth. For example, during the trial of Lorenzo Tizzano before the Inquisition at Venice in 1550, it was charged that the circle of the late Juan de Valdés (died 1541) at Naples had included such individuals.[8] Early Unitarians, often called Socinians, after Laelio Sozzini who first published the first unitarian analysis of John's Logos in 1550, were sometimes accused of denying the virgin birth, but mainly only denied the pre-existence of Christ in heaven. For Sozzini's better known nephew Fausto Sozzini the miraculous virgin birth was the element in their belief which removed the need for the pre-existence to which they objected.[9] The Socinians in fact excommunicated from their number the translator of the first Bible in Belarusian, Symon Budny, for his denial of the virgin birth.[10]

A large scale change among Unitarians to acceptance of a human father for Jesus took place only in the time of Joseph Priestley.[11] The young Samuel Taylor Coleridge was an example of what he called "a psilanthropist, one of those who believe our Lord to have been the real son of Joseph"[12] but later in life Coleridge decisively rejected this idea and accepted traditional Christian belief in the virgin birth.[13][14][15]

19th–21st centuries

Biblical scholars, churchmen, and theologians who have notably rejected the virgin birth include:

- Albrecht Ritschl, nineteenth-century German Lutheran theologian, considered one of the fathers of Liberal Protestantism.[16]

- Harry Emerson Fosdick, American Baptist pastor, prominent proponent of Liberal Protestantism. In a famous 1922 sermon delivered from the pulpit of First Presbyterian Church in New York, titled "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?", Fosdick called the Virgin Birth into question, saying it required belief in "a special biological miracle."[17]

- Fritz Barth, Swiss Reformed minister, and father of Karl Barth. Fritz's views cost him at least two significant promotions.[18]

- James A. Pike, Episcopal bishop of California (1958–1966), who first declared his doubt about the Virgin Birth in the December 21, 1960 issue of the journal Christian Century.[19][20]

- Martin Luther King's private writings show that he rejected biblical literalism; he described the Bible as "mythological", doubted that Jesus was born of a virgin and did not believe that the story of Jonah and the whale was true.[21]

- John Shelby Spong, retired Episcopal bishop of Newark, author of Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus, who following feminist scholar Jane Schaberg, wrote that, "A God who can be seen in the limp form of a convicted criminal dying alone on a cross on Calvary can surely also be seen in an illegitimate baby boy born through the aggressive and selfish act of a man sexually violating a teenage girl."[22]

- Marcus J. Borg, prominent member of the Jesus Seminar, author of numerous books, and co-author of The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions, who viewed the birth stories as "metaphorical narratives", and stated, "I do not think the virginal conception is historical, and I do not think there was a special star or wise men or shepherds or birth in a stable in Bethlehem. Thus I do not see these stories as historical reports but as literary creations."[23]

- John Dominic Crossan, prominent member of the Jesus Seminar, author of Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography, who has stated, "I understand the virginal conception of Jesus to be a confessional statement about Jesus' status and not a biological statement about Mary's body. It is later faith in Jesus as an adult retrojected mythologically onto Jesus as an infant."[24]

- Robert Funk, founder of the Jesus Seminar, and author of Honest to Jesus, who has asserted, "We can be certain that Mary did not conceive Jesus without the assistance of human sperm. It is unclear whether Joseph or some other unnamed male was the biological father of Jesus. It is possible that Jesus was illegitimate."[25]

- Jane Schaberg, feminist biblical scholar and author of The Illegitimacy of Jesus, who contended that Matthew and Luke were aware that Jesus had been conceived illegitimately, probably as a result of rape, and had left hints of that knowledge, even though their main purpose was to explore the theological significance of Jesus' birth.[26]

- Uta Ranke-Heinemann, who contends that the virgin birth of Jesus was meant—and should be understood—as an allegory of a special initiative of God, comparable to God's creation of Adam, and in line with legends and allegories of antiquity.[27]

- David Jenkins, Bishop of Durham from 1984 until 1994, was the first senior Anglican clergyman to come to the attention of the UK media for his position that "I wouldn't put it past God to arrange a virgin birth if he wanted. But I don't think he did."[28]

- Gerd Lüdemann, German New Testament scholar and historian, member of the Jesus Seminar, and author of Virgin Birth? The Real Story of Mary and Her Son Jesus, argued that early Christians had developed the idea of a virgin birth as a later "reaction to the report, meant as a slander but historically correct, that Jesus was conceived or born outside wedlock. ... It has a historical foundation in the fact that Jesus really did have another father than Joseph and was in fact fathered before Mary's marriage, presumably through rape."[29]

- Robin Meyers, United Church of Christ minister, proponent of Progressive Christianity, and author of Saving Jesus From the Church: How to Stop Worshiping Christ and Start Following Jesus. Asserts that "A beautiful, but obviously contrived, tale is the virgin birth, which may have been used to cover a scandal."[30]

Sects and denominations

The Divine Principle, the textbook of the Unification movement (also called the Unification Church), a new religious movement founded in South Korea, does not include the teaching that Zechariah was the father of Jesus; however some of its members hold that belief. Notably, this view is advanced by Young Oon Kim, citing the work of British liberal theologian Leslie Weatherhead in her book Unification Theology (1980).[31][32][33][34]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite), founded by James Jesse Strang, rejects the virgin birth and believes that Jesus' father was Joseph, husband of Mary.[35]

See also

- Virgin birth of Jesus

- Arianism

- King Jesus (novel) (semi-historical novel)

- Adam God doctrine (while not necessarily denying the Virgin Birth per-se, implies sexual relations between God the Father and Mary)

References

- ^ Marthaler, Berard L. (2007). The Creed: the apostolic faith in contemporary theology. 3rd ed. ISBN 0-89622-537-2 page 129

- ^ The Westminster handbook to patristic theology by John Anthony McGuckin 2004 ISBN 0-664-22396-6 page 286

- ^ Thinking of Christ: proclamation, explanation, meaning by Tatha Wiley 2003 ISBN 0-8264-1530-X page 257

- ^ Machen, J. Gresham (1958) [1st pub. Harper: 1930]. The Virgin Birth of Christ. London: James Clarke & Co. pp. 22–36. ISBN 978-0-227-67630-1.

Apparently Jerome does not say in so many words that the Ebionites denied the virgin birth. But he seems to contrast their view with the acceptance of the doctrine on the part of the Nazarenes. In one place, Epiphanius says that he does not [...] the terminology (at least) differs; for by these writers those who accepted the virgin birth are called "Nazarenes," while the term Ebionites is reserved for those who denied it. Epiphanius' terminology has been followed by some scholars[.]

- ^ Ådna, Jostein (2005). The Formation of the Early Church. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 269. ISBN 3161485610.

...he makes a distinction between two kinds of Ebionites: one group denied the virgin birth, others did not. When describing the latter group, Eusebius notes that, despite the fact that they accepted the virgin birth, they were still heretics...

- ^ Carr, A. Wesley (2005). Angels and Principalities, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01875-7 page 131

- ^ Laato, Antti (2016-04-11). "Celsus, Toledot Yeshu and Early Traces of Apology for Virginal Birth of Jesus". Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis. 27: 61–80. doi:10.30674/scripta.66569. ISSN 2343-4937.

- ^ Earl Morse Wilbur A History of Unitarianism: Socinianism and its Antecedents 1946 Page 92 In the trial of Lorenzo Tizzano (or Tizziano) before the Inquisition at Venice in 1550, evidence was given that in Valdes's circle at Naples there were heretics that denied the virgin birth...

- ^ David Munroe Cory Faustus Socinus 1932 p. 103 "We find that all these doctrines, considered essential by the orthodox, are completely repudiated by Socinus. ... Christ's unique divine sonship (divina filiatio) is guaranteed for Socinus by the virgin birth."

- ^ The Jews in old Poland, 1000-1795 ed. Antony Polonsky, Jakub Basista, Andrzej Link-Lenczowski - 1993 p. 32 "Budny rejected the eternality of Christ and, in the notes to his translation of the New Testament, denied the Virgin birth, assenting that Jesus was Joseph's son. Even among heretical leaders Szymon Budny was considered a heretic and they would have nothing to do with him."

- ^ J. D. Bowers Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America 0271045817 2010 p. 33 "As a result, Priestley spent the remainder of the decade embroiled in a public battle with the Reverend Samuel Horsley, ... the virgin birth was ascriptural, and the doctrine of the atonement was contrived over centuries of theological errors."

- ^ Coleridge "I was a psilanthropist, one of those who believe our Lord to have been the real son of Joseph." 1817 Biog. Lit. i 168, in Cyclopædia of Biblical, theological, and ecclesiastical literature, Volume 2 by John McClintock, James Strong 1894 p. 406.

- ^ Samuel Taylor Coleridge by Basil Willey, p. 156.

- ^ Cyclopædia of Biblical, theological, and ecclesiastical literature, Volume 2 by John McClintock, James Strong 1894 p. 406.

- ^ Bowers, J. D., Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America, 2007, ISBN 0-271-02951-X, p. 36.

- ^ Frei, Hans Wilhelm (March 18, 2018). "Albrecht Ritschl". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ Mohler Jr, R. Albert (December 24, 2003). "Can a Christian deny the Virgin Birth?". BaptistPress.com. First Person. Southern Baptist Convention. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Dustin Resch, Barth's Interpretation of the Virgin Birth: A Sign of Mystery, 2016: "...to have cost him at least two significant promotions. Even given the unhappy consequences of Fritz Barth's denial of the virgin birth, such a position was well established in the mainstream of European biblical and theological scholarship."[page needed]

- ^ Robertson, David M. (2004). A Passionate Pilgrim: A Biography of Bishop James A. Pike. Knopf.

- ^ Douthat, Ross (2012). Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics. Free Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9781439178300.

- ^ Chakko Kuruvila, Matthai (January 15, 2007). "Writings show King as liberal Christian, rejecting literalism". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Spong, John Shelby (1992). Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus, HarperSanFrancisco, p. 185. ISBN 9780060675134.

- ^ Borg, Marcus J. (1998). "The Meaning of the Birth Stories", in Marcus J. Borg and N. T. Wright, The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions, HarperSanFrancisco, p. 179. ISBN 0-06-060875-7.

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic (1994). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography, HarperSanFrancisco, p. 23. ISBN 9780060616618.

- ^ Funk, Robert W. (1996). Honest to Jesus: Jesus for a New Millennium. HarperSanFrancisco, p. 294. ISBN 9780060627577.

- ^ Schaberg, Jane (1987). The Illegitimacy of Jesus: A Feminist Interpretation of the Infancy Narratives. Harper & Row. ISBN 0062546880 pp. 33-34. Reprint: Crossroad, 1990. Expanded 20th Anniversary Edition: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2006. ISBN 9781905048830.

- ^ Ranke-Heinemann, Uta. Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven. Garden City: Doubleday, 1990. ISBN 0-385-26527-1.

- ^ Nineham, Dennis (2016-09-04). "The Right Rev David Jenkins obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ Lüdemann, Gerd (1998). Virgin Birth? The Real Story of Mary and Her Son Jesus. London: SCM Press ISBN 9780334027249; Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International. ISBN 9781563382437 pp. 60, 138.

- ^ Meyers, Robin R. (2009). Saving Jesus From the Church: How to Stop Worshiping Christ and Start Following Jesus. HarperOne. ISBN 9780061568213 p. 40.

- ^ Religious Requirements and Practices of Certain Selected Groups: A Handbook for Chaplains, By U. S. Department of the Army, Published by The Minerva Group, Inc., 2001, ISBN 0-89875-607-3, ISBN 978-0-89875-607-4, page 1–42. Google books listing

- ^ Sontag, Fredrick (1977). Sun Myung Moon and the Unification Church. Abingdon. pp. 102–105. ISBN 0-687-40622-6.

- ^ Weatherhead, L.D. (1965). The Christian Agnostic. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 59–63. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2022-03-15.

- ^ Tucker, Ruth A. (1989). Another Gospel: Cults, Alternative Religions, and the New Age Movement. Grand Rapids: Academie Books/Zondervan. ISBN 0-310-25937-1 pp. 250-251

- ^ Brasich, Adam S. “Jesus Christ, Son of Man: James J. Strang's Apologetic Christology.” Journal of Mormon History, vol. 45, no. 3, 2019, pp. 26–50. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jmormhist.45.3.0026. Accessed 14 Dec. 2020.