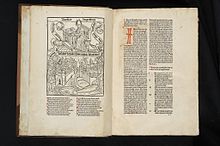

The City of God

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

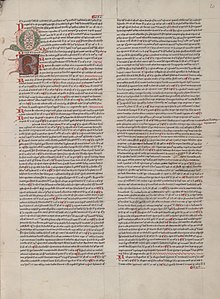

The City of God , opening text, manuscript c. 1470 | |

| Author | Augustine of Hippo |

|---|---|

| Original title | De civitate Dei contra paganos |

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Christian philosophy, Christian theology, Neoplatonism |

| Genre | theology |

Publication date | Completed work published AD 426 |

| Publication place | Western Roman Empire |

| Media type | Manuscript |

| 239.3 | |

| LC Class | BR65 .A64 |

Original text | De civitate Dei contra paganos at Latin Wikisource |

| Translation | The City of God at Wikisource |

| Part of a series on |

| Augustine of Hippo |

|---|

|

| Augustinianism |

| Works |

| Influences and followers |

| Related topics |

| Related categories |

| Part of a series on |

| Neoplatonism |

|---|

|

|

|

On the City of God Against the Pagans (Latin: De civitate Dei contra paganos), often called The City of God, is a book of Christian philosophy written in Latin by Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD. The book was in response to allegations that Christianity brought about the decline of Rome and is considered one of Augustine's most important works, standing alongside The Confessions, The Enchiridion, On Christian Doctrine, and On the Trinity.[1] As a work of one of the most influential Church Fathers, The City of God is a cornerstone of Western thought, expounding on many questions of theology, such as the suffering of the righteous, the existence of evil, the conflict between free will and divine omniscience, and the doctrine of original sin.[2][3]

Background

The sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 left Romans in a deep state of shock, and many Romans saw it as punishment for abandoning traditional Roman religion in favor of Christianity. In response to these accusations, and in order to console Christians, Augustine wrote The City of God as an argument for the truth of Christianity over competing religions and philosophies. He argues that Christianity was not responsible for the Sack of Rome but instead responsible for Rome's success. Even if the earthly rule of the Empire was imperiled, it was the City of God that would ultimately triumph. Augustine's focus was Heaven, a theme of many Christian works of Late Antiquity. Despite Christianity's designation as the official religion of the Empire, Augustine declared its message to be spiritual rather than political. Christianity, he argued, should be concerned with the mystical, heavenly city, the New Jerusalem, rather than with earthly politics.

The book presents human history as a conflict between what Augustine calls the Earthly City (often colloquially referred to as the City of Man, and mentioned once on page 644, chapter 1 of book 15) and the City of God, a conflict that is destined to end in victory for the latter. The City of God is marked by people who forgo earthly pleasure to dedicate themselves to the eternal truths of God, now revealed fully in the Christian faith. The Earthly City, on the other hand, consists of people who have immersed themselves in the cares and pleasures of the present, passing world.[4]

Augustine's thesis depicts the history of the world as universal warfare between God and the Devil. This metaphysical war is not limited by time but only by geography on Earth. In this war, God moves (by divine intervention, Providence) those governments, political/ideological movements and military forces aligned (or aligned the most) with the Catholic Church (the City of God) in order to oppose by all means—including military—those governments, political/ideological movements and military forces aligned (or aligned the most) with the Devil (the City of the World).

This concept of world history guided by Divine Providence in a universal war between God and the Devil is part of the official doctrine of the Catholic Church as most recently stated in the Second Vatican Council's Gaudium et Spes document: "The Church ... holds that in her most benign Lord and Master can be found the key, the focal point and the goal of man, as well as of all human history ... all of human life, whether individual or collective, shows itself to be a dramatic struggle between good and evil, between light and darkness ... The Lord is the goal of human history the focal point of the longings of history and of civilization, the center of the human race, the joy of every heart and the answer to all its yearnings."

Structure

- Part I (Books I–X): a polemical critique of Roman religion and philosophy, corresponding to the Earthly City

- Book I–V: A critique of pagan religion

- Book I: a criticism of the pagans who attribute the sack of Rome to Christianity despite being saved by taking refuge in Christian churches. The book also explains good and bad things happen to righteous and wicked people alike, and it consoles the women violated in the recent calamity.

- Book II: a proof that because of the worship of the pagan gods, Rome suffered the greatest calamity of all, that is, moral corruption.

- Book III: a proof that the pagan gods failed to save Rome numerous times in the past from worldly disasters, such as the sack of Rome by the Gauls.

- Book IV: a proof that the power and long duration of the Roman empire was due not to the pagan gods but to the Christian God.

- Book V: a refutation of the doctrine of fate and an explanation of the Christian doctrine of free will and its consistency with God's omniscience. The book proves that Rome's dominion was due to the virtue of the Romans and explains the true happiness of the Christian emperors.

- Book VI–X: A critique of pagan philosophy

- Book VI: a refutation of the assertion that the pagan gods are to be worshipped for eternal life (rather than temporal benefits). Augustine claimed that even the esteemed pagan theologist Varro held the gods in contempt.

- Book VII: a demonstration that eternal life is not granted by Janus, Jupiter, Saturn, and other select gods.

- Book VIII: an argument against the Platonists and their natural theology, which Augustine views as the closest approximation of Christian truth, and a refutation of Apuleius' insistence of the worship of demons as mediators between God and man. The book also contains a refutation against Hermeticism.

- Book IX: a proof that all demons are evil and that only Christ can provide man with eternal happiness.

- Book X: a teaching that the good angels wish that God alone is worshipped and a proof that no sacrifice can lead to purification except that of Christ.

- Book I–V: A critique of pagan religion

- Part II (Books XI–XXII): discussion on the City of God and its relationship to the Earthly City

- Books XI–XIV: the origins of the two cities

- Book XI: the origins of the two cities from the separation of the good and bad angels, and a detailed analysis of Genesis 1.

- Book XII: answers to why some angels are good and others bad, and a close examination of the creation of man.

- Book XIII: teaching that death originated as a penalty for Adam's sin, the fall of man.

- Book XIV: teachings on the original sin as the cause for future lust and shame as a just punishment for lust.

- Books XV–XVIII: the history or progress of the two cities, including foundational theological principles about Jews.

- Book XV: an analysis of the events in Genesis between the time of Cain and Abel to the time of the flood.

- Book XVI: the progress of the two cities from Noah to Abraham, and the progress of the heavenly city from Abraham to the kings of Israel.

- Book XVII: the history of the city of God from Samuel to David and to Christ, and Christological interpretations of the prophecies in Kings and Psalms.

- Book XVIII: the parallel history of the earthly and heavenly cities from Abraham to the end. Doctrine of Witness, that Jews received prophecy predicting Jesus, and that Jews are dispersed among the nations to provide independent testimony of the Hebrew Scriptures.

- Books XIX–XXII: the deserved destinies of the two cities.

- Book XIX: the end of the two cities, and the happiness of the people of Christ.

- Book XX: the prophecies of the Last Judgment in the Old and New Testaments.

- Book XXI: the eternal punishment for the city of the devil.

- Book XXII: the eternal happiness for the saints and explanations of the resurrection of the body.

- Books XI–XIV: the origins of the two cities

English translations

- The City of God. Translation by William Babcock, notes by Boniface Ramsey. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2012.

- The City of God against the Pagans. Translation by R. W. Dyson. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-46475-7

- The City of God. Translation by Henry Bettenson. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1972.

- The City of God: Volumes XVI–XVIII Translation by Eva Matthews Sanford with William M. Green. Loeb Classical Library 415, 1965.

- City of God. Translation by William M. Green. Cambridge University Press, 1963

- The City of God. Translation by Gerald G. Walsh, S. J., et al. Introduction by Étienne Gilson. New York: Doubleday, Image Books, 1958.

- The City of God. Translation by Marcus Dods. Introduction by Thomas Merton. New York: The Modern Library, a division of Random House, Inc., 1950. First published: 1871.

- The City of God. Translation by John Healey. Introduction by Ernest Barker. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1945.

- Of the Citie of God. Translation by John Healey. Notes by Juan Luis Vives. London: George Eld, 1610.

References

- ^ Comstock, Patrick. "Historical Context for City of God by Augustine". Columbia College. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Brandon (July 2014). "Augustine: Advocate of Free Will, Defender of Predestination" (PDF). Journal of Undergraduate Research – via University of Notre Dame.

- ^ Tornau, Christian (25 September 2019). "Saint Augustine". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Mommsen, Theodor (1951). "St. Augustine and the Christian Idea of Progress: The Background of the City of God". Journal of the History of Ideas. 12 (3): 346–374. doi:10.2307/2707751. JSTOR 2707751.

- ^ "De civitate Dei; Epigrammata in S. Maximinum". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

Further reading

- Horn, Christoph (1997). Augustinus. De civitate dei. Klassiker auslegen, vol. 11. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, ISBN 3-05-002871-8.

- Vareille, Agnès (2023). Saint Augustin et l'écriture polyphonique. Citations classiques et genèse de la pensée dans la Cité de Dieu. Turnhout: Brepols, ISBN 9782851213280 (see the English summary in the Review by James J. O'Donnell at Bryn Mawr Classical Review).

- Wetzel, James (2012). Augustine's City of God: A Critical Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-57644-4.

External links

Media related to De Civitate Dei at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Civitate Dei at Wikimedia Commons Works related to The City of God at Wikisource

Works related to The City of God at Wikisource Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: De civitate Dei

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: De civitate Dei- De civitate dei (in Latin) – The Latin Library.

- The City of God – Dods translation, New Advent. Excerpts only.

The City of God public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Dods translation)

The City of God public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Dods translation)- The City of God – Marcus Dods translation, CCEL

- Lewis E 197 Expositio in civitatem dei S. Augustini (Commentary on St. Augustine's City of God) at OPenn

Texts about the work