William McKinley 1896 presidential campaign

| William McKinley for President | |

|---|---|

| |

| Campaign | U.S. presidential election, 1896 |

| Candidate | William McKinley 39th Governor of Ohio (1892–1896) Garret Hobart President of the New Jersey Senate (1881–1882) |

| Affiliation | Republican Party |

| Status | Elected: November 3, 1896 |

| Headquarters | Chicago, New York City |

| Key people |

|

| Receipts | US$3,500,000 to $16,500,000 (estimated)[1] |

In 1896, William McKinley was elected President of the United States. McKinley, a Republican and former Governor of Ohio, defeated the joint Democratic and Populist nominee, William Jennings Bryan, as well as minor-party candidates. McKinley's decisive victory in what is sometimes seen as a realigning election ended a period of close presidential contests, and ushered in an era of dominance for the Republican Party.

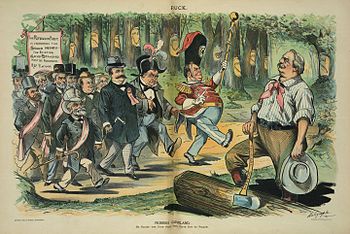

McKinley was born in 1843 in Niles, Ohio. After service as an Army officer in the Civil War, he became a lawyer and settled in Canton, Ohio. In 1876 he was elected to Congress, and he remained there most of the time until 1890, when he was defeated for re-election in a gerrymandered district. By this time he was considered a likely presidential candidate, especially after being elected governor in 1891 and 1893. McKinley had incautiously co-signed the loans of a friend, and demands for repayment were made on him when his friend went bankrupt in the Panic of 1893. Personal insolvency would have removed McKinley as a factor in the 1896 campaign, but he was rescued from this by businessmen who supported him, led by his friend and political manager, Mark Hanna. With that obstacle removed, Hanna built McKinley's campaign organization through 1895 and 1896. McKinley refused to deal with the eastern bosses such as Thomas Platt and Matthew Quay, and they tried to block his nomination by encouraging state favorite son candidates to run and prevent McKinley from getting a majority of delegate votes at the Republican National Convention, which might force him to make deals on political patronage. Their efforts were in vain, as the large, efficient McKinley organization swept him to a first ballot victory at the convention, with New Jersey's Garret Hobart as his running mate.

McKinley was a noted protectionist, and was confident of winning an election fought on that question. But it was free silver that became the issue of the day, with Bryan capturing the Democratic nomination as a foe of the gold standard. Hanna raised millions for a campaign of education with trainloads of pamphlets to convince the voters that free silver would be harmful, and once that had its effect, even more were printed on protectionism. McKinley stayed at home in Canton, running a front porch campaign and reaching millions through newspaper coverage of the speeches he gave to organized groups of people. This contrasted with Bryan, who toured the nation by rail in his campaign. Supported by the well-to-do, urban dwellers, and prosperous farmers, McKinley won a majority of the popular vote and an easy victory in the Electoral College. McKinley's systemized approach to gaining the presidency laid the groundwork for modern campaigns, and he forged an electoral coalition that would keep the Republicans in power most of the time until 1932.

Background

William McKinley was born in Niles, Ohio in 1843. He left college to work as a teacher, and enlisted in the Union Army when the American Civil War broke out in 1861. He served throughout the war, ending it as a brevet major. Afterwards, he attended Albany Law School in New York state, and was admitted to the bar in Ohio. He settled in Canton, Ohio; after practicing law there, he was elected to Congress in 1876, and except for short periods served there until 1891. In 1890 he was defeated for re-election, but he was elected governor the following year, serving two two-year terms.[2]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

39th Governor of Ohio

25th President of the United States

First term

Second term

Presidential campaigns

Legacy

|

||

In the latter part of the 19th century, Ohio was deemed a crucial battleground state; taking its electoral votes was thought essential for a Republican to win the White House. One way of, hopefully, assuring victory there was to nominate a son of Ohio.[3] Between 1865 and 1929, every Republican president who first gained his office by election (that is, rather than succeeding on the death of his predecessor) was born in Ohio.[4] Deadlocked Republican conventions in 1876, 1880, and 1888 turned to men born in Ohio, and in each case the nominee won the presidency. Thus, any successful Ohio Republican was a plausible president. One of McKinley's rivals among the Ohio contenders was Governor Joseph B. Foraker, but Foraker's light dimmed when he was defeated for a third two-year term in 1889.[5]

There were strong factional conflicts within the Ohio Republican party; one source of bitterness was the 1888 Republican National Convention. Ohio Republicans had endorsed the state's senior senator, John Sherman, for president. This was Sherman's third attempt at the Republican nomination; among his supporters were Cleveland industrialist Mark Hanna, and Governor Foraker, whom Hanna had to that point strongly supported. After repeated balloting, Sherman did not get close to the number of delegate votes needed to nominate, and when rumors swept the convention that the party's 1884 nominee, former Maine senator James G. Blaine, might enter the race, Foraker expressed willingness to support Blaine. This dealt a serious blow to Sherman's candidacy by showing division in his home state, and the nomination went to former Indiana senator Benjamin Harrison, who was Ohio-born and went on to be elected. McKinley had received some delegate votes, and his action in refusing to consider a candidacy while pledged to support Sherman impressed Mark Hanna. The industrialist was outraged at Foraker and abandoned him. McKinley and Hanna shared similar political views, including support for a tariff to protect and encourage American industry, and in the years following 1888, Hanna became a strong supporter of McKinley.[6]

Revenue from tariffs was then a major source of income for the federal government. There was no federal income tax, and tariff debates were passionate;[7] the 1888 presidential election had them as a major issue.[8] Many Democrats supported a tariff for revenue only—that is, the purpose of tariffs should be to finance government, not to encourage American manufacturers. McKinley disagreed with that and sponsored the McKinley Tariff of 1890. This act, passed by the Republican-dominated Congress, raised rates on imports to protect American industry. McKinley's tariff proved unpopular among many people who had to pay the increased prices, and was seen as a reason not only for his defeat for re-election to Congress in 1890, but also for the Republicans losing control of both House and Senate in that year's midterm elections.[9] Nevertheless, McKinley's defeat did not, in the end, damage his political prospects, as the Democrats were blamed for gerrymandering him out of his seat.[10]

Sometime between 1888 and 1890, McKinley decided to run for president, but to have a realistic chance of attaining that goal, he needed to regain office. Foraker's ambition then was the Senate—he planned to challenge Sherman in the legislative election to be held in January 1892[a]—and he agreed to nominate McKinley for governor at the state convention in Columbus.[11] McKinley was elected, and Sherman narrowly turned back Foraker's challenge with considerable help from Hanna.[12]

Harrison had proven unpopular even in his own party, and by the start of 1892, McKinley was talked about as a potential presidential candidate.[13] McKinley's name was not offered in nomination at the 1892 Republican National Convention, where he served as permanent chairman, but some delegates voted for him anyway, and he finished third behind Harrison (who won a first ballot victory) and Blaine. Hanna had sought support from delegates, but his and McKinley's strategy is uncertain, due to lack of surviving documents. According to Hanna biographer William T. Horner, "McKinley's behavior at the convention supports the idea that he liked the attention but was not ready for a campaign".[14] According to McKinley biographer H. Wayne Morgan, many delegates "saw in [McKinley] their nominee for 1896".[15]

Gaining the nomination

Preparing for a run

Harrison was defeated in the November 1892 election by former president Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, who returned to the White House in March 1893. President Harrison left office proclaiming the nation's prosperity, but in May, amid economic uncertainty that caused many people to convert assets into gold, the stock market crashed, and many firms went bankrupt. The depression that ensued became known as the Panic of 1893.[16] Among those who became insolvent in 1893 was a McKinley friend, Robert Walker.[17] McKinley had co-signed promissory notes for Walker, and thought the total to be $17,000. Walker had deceived McKinley, telling the governor that fresh loans were renewals of old ones, and the total indebtedness, for which McKinley had made himself liable, was over $130,000. That sum was beyond McKinley's means, and he planned to resign and earn the money as a lawyer.[18] He was rescued by Hanna and other wealthy supporters, who raised the money to pay the loans.[19] According to McKinley biographer Kevin Phillips, the governor's backers "paid off the cosigned notes so that McKinley—by now, the probable next president—did not need to go back to practicing law".[20]

The public sympathized with McKinley for his financial trouble,[21] and he was easily re-elected as governor in late 1893.[22] At that time, the United States, for all practical purposes, was on the gold standard. Many Democrats, and some Republicans, felt that the gold standard limited economic growth, and supported bimetallism, making silver legal tender, as it had been until the passage of the Coinage Act of 1873. Doing so would likely be inflationary, permitting holders of silver to deposit bullion at the mints, and receive payment for about twice the silver's 1896 market value. Many farmers, faced with the long decline in agricultural prices that persisted through the first half of the 1890s, felt that bimetallism would expand the money supply and make it easier to pay their debts.[23] Cleveland was a firm supporter of the gold standard, and believed the massive amounts of silver-backed currency issued pursuant to the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 had helped crash the economy. In 1893 he forced through the act's repeal, outraging western Democrats such as Nebraska Congressman William Jennings Bryan.[24] The Democratic Congress in 1894 passed the Wilson–Gorman Tariff, significantly lowering many rates from the McKinley Tariff of 1890.[25] The economy did not improve in 1894, and other Cleveland actions, such as federal intervention to halt the Pullman strike, further split his party,[26]

The 1894 election campaign saw the Democrats divided, and the electorate further split by the new People's Party (or Populists), which had emerged from the agricultural discontent. There were more demands for McKinley to speak than he could possibly fulfill. Campaigning throughout the eastern half of the country on behalf of Republican candidates, and venturing even to New Orleans in the Democratic Solid South, McKinley spoke to large, enthusiastic crowds as often as 23 times in a day. According to his biographer Margaret Leech, "McKinley's fervor was irresistible to his audiences. He was better than a spellbinder. He was a vote-getter. The whirlwind campaign of the Governor of Ohio was a sensation of the autumn."[27] The 1894 elections saw the Democrats suffer the greatest losses by a majority party in congressional history, as the Republicans again took control of both houses.[28]

First modern primary campaign

The outcome of the 1894 elections made it increasingly likely that a Republican would be the next president. At the time, the presidential nominating process started much later than it subsequently would, and McKinley, in quietly organizing his campaign with Hanna's aid in the early months of 1895, was alone among the candidates in acting so early. Other potential Republican candidates were former president Harrison, incoming Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed of Maine, Iowa Senator William B. Allison, and several state favorite sons, such as Illinois Senator Shelby Cullom. If former president Harrison entered the race, he would immediately become a major contender, and uncertainty over his status hung over the race in 1895.[29] At the time, unless there was an incumbent elected Republican president, the nomination was generally not decided until the convention, with state political bosses and delegates exacting a price for their support. A candidate's efforts to gain the nomination did not begin until shortly before the state delegate conventions in the spring of the election year, where fights over the makeup of the delegation often focused on who would be on it, rather than who delegates would support. McKinley and Hanna decided on a systematic nationwide effort to gain the nomination, employing what onetime presidential adviser Karl Rove—author of a 2015 book on the 1896 race—called "the first modern primary campaign".[b][30]

To devote himself full-time to McKinley's presidential campaign, Hanna in 1895 turned over management of his companies to his brother Leonard, and rented a house in Thomasville, Georgia, expressing a dislike for Cleveland's winters. He was joined there by William and Ida McKinley in early 1895. The location was a plausibly nonpolitical vacation spot for McKinley, and also permitted him to meet many southern Republicans, including blacks. Although southern Republicans rarely had local electoral success, they elected a substantial number of delegates to the national convention.[31] McKinley and Hanna hosted many southern Republican leaders in Thomasville, subsidizing those who did not have the money to come, and made many converts. The governor also traveled in the South; in Savannah at the end of March 1895, he became the first presidential hopeful in American history to address an audience of blacks when he spoke at an African American church.[32] By the time he left Thomasville, he had gained the support of the majority of likely southern delegates;[33] Platt wrote mournfully in his autobiography that Hanna "had the South practically solid before some of us awakened".[34]

In giving attention to national affairs, McKinley neglected his home front in Ohio, and when the Republican state convention met in Zanesville in May 1895, it proved to be controlled by the resurgent Foraker, who sought the Senate seat to be filled by the Ohio General Assembly in January 1896. That convention endorsed McKinley for president and Foraker for Senate, and nominated Foraker supporters for state and party offices, including Asa Bushnell to succeed McKinley as governor.[35] McKinley realized that it would be risky to have a faction hostile to the presidential candidate within his home state, and sought an alliance, campaigning for Bushnell and for a Republican legislature that would send Foraker to Washington. The voters chose Bushnell and gave the state Republicans a large majority in the legislature. In January 1896, Foraker was overwhelmingly elected (to take office in March 1897), and McKinley gained Foraker's agreement to support him for president, assuring party political peace at home.[36]

During 1895, Hanna journeyed east to meet with the political bosses there, including Pennsylvania Senator Matthew Quay and Thomas C. Platt of New York. He returned to report that the bosses were willing to assure McKinley's nomination in exchange for a pledge to give them control over patronage in their states and a promise in writing that Platt would be Treasury Secretary. McKinley was unwilling to deal, seeking a nomination without strings, and Hanna, though noting that this made his task much harder, undertook to get it. McKinley decided on a theme for his nomination campaign, "The People Against the Bosses".[37] With Hanna's aid, McKinley found talented men to run the state organizations, who would in turn find locals to ensure McKinley triumphed at the series of conventions that would elect delegates to the June 1896 Republican convention in St. Louis. Notable among these appointments was Charles G. Dawes in Illinois, a young banker and entrepreneur who had recently moved to Chicago from Nebraska, where he had known Congressman Bryan. In trying to organize Illinois for McKinley, Dawes faced the enmity of the local Republican bosses, who preferred to take a delegation to St. Louis that would support Senator Cullom until the bosses made the right deal.[38]

McKinley left office as governor in January 1896. In February, Harrison made it clear that he would not seek a third nomination. Hanna's operatives immediately organized Harrison's home state of Indiana for McKinley with a haste that the former president privately found unseemly. By early 1896, the Reed and Allison campaigns were beginning to form themselves, but they had little luck in Indiana. McKinley challenged his rivals everywhere except in states, such as Iowa, that he deemed had serious candidates like Senator Allison. The favorite son candidacies of Minnesota Senator Cushman K. Davis and former Nebraska senator Charles F. Manderson fell victim to the McKinley forces, well-financed by Hanna, who took their states away from them.[39] McKinley was disliked by the American Protective Association, an anti-Catholic group angered that as governor he had appointed to office members of that faith. Their wide pamphleting caused Hanna to act against falsehoods that his candidate was a Catholic.[40]

According to historian Stanley Jones in his account of the 1896 campaign, "another feature common to the Reed and Allison campaigns was their failure to make headway against the tide which was running toward McKinley. In fact, both campaigns from the moment they were launched were in retreat."[41] In March and April 1896, state conventions in Ohio, Michigan, California, Indiana, and other states elected delegates to the national convention, instructed to vote for McKinley.[34] In New England, McKinley made inroads into Reed's regional support, as New Hampshire proclaimed no preference between the Speaker and McKinley, and the Vermont convention expressed support for McKinley.[42] The Ohioan was not successful everywhere; Iowa remained loyally behind Allison, Morton won a majority of the New York delegation, and the bosses were successful in denying McKinley in New Mexico Territory and Oklahoma Territory.[43] The contest was still undetermined going into the April 29 Illinois state convention, with the McKinley forces led by Dawes against the local bosses. McKinley gained most of Illinois' delegates, giving him a sizable lead, and influencing remaining state conventions to jump on his bandwagon.[44]

McKinley remained well ahead when the state conventions concluded, leaving his opponents' only hope the Republican National Committee (RNC), which would make initial rulings on which delegates would be seated; there were contested seats or rival delegations in several states, and rulings against McKinley could still deprive him of a first-ballot majority. When the RNC met in mid-June, just prior to the convention, McKinley was easily victorious in almost all cases.[45]

Republican convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention convened at the Wigwam, a temporary structure in St. Louis, on June 16. With most credentials battles settled in McKinley's favor, the roll of delegates drawn up by the RNC heavily favored the Ohioan, though Reed, Allison, Morton and Quay remained in the race. The credentials report served as a test vote, which the McKinley forces won easily. Hanna, who was a delegate from Ohio, was in full control of the convention.[46][47]

Many westerners, including Republicans, were supporters of free silver. McKinley's advisors had anticipated there would be strong feelings about the currency question, and pressed the candidate for a decision on what the party platform should say on the subject. McKinley had hoped to avoid this issue; his surrogates had presented him as firmly for the gold standard in the East, where support for that policy was strong. Western supporters, who often favored silver, were told he was sympathetic to the bimetallic cause. In the following years, several McKinley associates, including publisher H. H. Kohlsaat and Wisconsin's Henry C. Payne, took credit for including an explicit mention of the gold standard in the platform's currency plank (for they deemed it vital to the Republican victory in November), but it was not inserted in the draft until Hanna consulted with McKinley by telephone. The silver Republicans from the West were led by Colorado Senator Henry M. Teller, who drafted a plank promoting free silver, only to see it voted down in the drafting committee, and in the full Platform Committee.[c] Teller was determined to have the full convention vote on his language, although it was certain he would lose as most Republican delegates favored the gold standard. The debate was held on June 18. After Teller's minority report was voted down and the gold plank adopted by an overwhelming majority, 23 delegates, including Teller and his Senate colleagues Frank Cannon of Utah and Fred Dubois of Idaho, walked out of the convention and thus left the Republican Party. Amid a tumultuous scene, an angry Hanna was seen standing on a chair, shouting at the departing men, "Go! Go! Go!"[48]

Although Platt desired a recess, Hanna refused, wanting the convention to complete its work that day, and the delegates proceeded to the presidential nomination. McKinley had insisted that Foraker nominate him to demonstrate the unity of the Ohio Republican Party, and after some reluctance by the senator-elect, who feared blame if anything went wrong, Foraker agreed. McKinley was waiting with family and friends at his house in Canton, being kept up to date by telegraph and telephone. He was able to listen to part of Foraker's speech, and the tremendous reception that met it, over the phone line. McKinley was easily nominated on the first ballot, with Reed his nearest competitor. Canton erupted in celebration, with McKinley making speech after speech to the townsfolk and to those who poured in that day by rail from across Ohio, even from his birthplace of Niles.[49]

This left the question of the vice presidential candidate. McKinley had offered the second place on the ticket to Reed, who had refused it. Platt wanted Morton, who had been vice president under Harrison; the New York governor did not want it, and McKinley did not want him. It was usual at that time for major-party tickets to have one candidate from Ohio or Indiana, and the other from New York, but with that state having supported Morton for the nomination, putting a New Yorker on the ticket would be an unmerited reward.[50] RNC vice chairman Garret Hobart was from Paterson, New Jersey, near to New York City. He was a businessman, lawyer, and former state legislator, and was acceptable to Hanna and other Republican backers while being popular among party activists. Several days before the convention, McKinley chose him as running mate, though no announcement was made.[51] At the convention, Hobart expressed surprise in a letter to his wife,[52] but his selection had been strongly rumored and buttons with his name and McKinley's seen in St. Louis.[50] Delegates ratified the selection of Hobart, nominating him on the first ballot.[52]

General election campaign

Getting an opponent

In the days after the Republican convention, McKinley remained in Canton. Hanna had been elected chairman of the RNC during the convention; he established campaign headquarters in Chicago,[d] in the electorally-crucial Midwest, appointed an executive committee and began to organize the campaign, which as chairman was his responsibility. McKinley oversaw the activities of Hanna and other key managers, and addressed delegations of workers who came to visit him. He met with Hobart, who came to Canton on a brief visit on June 30, 1896, and who joined his running mate in speaking to a crowd of visitors. In his speeches, McKinley concentrated on tariffs, which he expected to dominate the campaign, and gave short shrift to the currency question.[53] As McKinley awaited his opponent, he privately commented on the nationwide debate over silver, stating to his Canton crony, Judge William R. Day, "This money matter is unduly prominent. In thirty days you won't hear anything about it."[54] The future Secretary of State and Supreme Court justice responded: "In my opinion in thirty days you won't hear of anything else."[54]

At the time McKinley was nominated, it was not clear who his Democratic rival would be. Cleveland's opponents within his party had mobilized into an organized effort to take over the Democratic Party and pass a platform supporting free silver. The platform was deemed of highest priority, and only once that fight was won was a candidate for president to be considered. Despite this resolution, several Democrats sought the nomination, with the foremost being former Missouri representative Richard P. Bland and former Iowa governor Horace Boies. Others either seeking or spoken of for the nomination included South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman, Senator Joseph C. Blackburn of Kentucky, and former Nebraska representative William Jennings Bryan.[55]

Dawes had known Bryan in Nebraska, and predicted that if the former congressman got to address the convention, he would use his skills as a speaker to stampede it to a nomination. McKinley and Hanna mocked Dawes, telling him that Bland would be the Democratic choice.[56][57] The 1896 Democratic National Convention opened in Chicago on July 7, with the silverites in full control; they drafted a platform supporting free silver. The final speaker during the debate on the platform was former congressman Bryan, who with Dawes in the gallery delivered a speech decrying the gold standard that to Democrats, according to Phillips, was "messianic—a call to arms".[57] Dawes deemed his friend's Cross of Gold speech magnificent, though with "pitiably weak" logic, but it won Bryan the presidential nomination, and Phillips noted that the address "unnerved Midwestern Republicans, mindful of their own distrust of the East, and threw a weighty stone into the quiet pool of June GOP electoral assumptions".[57]

When journalist Murat Halstead telephoned McKinley from Chicago to inform him that Bryan would be nominated, he responded dismissively and hung up the phone.[58] Bryan's nomination briefly gratified the Republicans, believing that his selection would lead to an easy victory for McKinley.[59] In those days when the presidential campaign did not begin in earnest until September, Hanna had planned a vacation while McKinley anticipated a quiet summer. The Republicans were caught by surprise by the wave of enthusiasm that Bryan's speech and nomination caused, and scuttled these plans; as Hanna wrote to McKinley on July 16, "the Chicago convention has changed everything".[60]

Fundraising and organization

Hanna quickly realized that the currency issue struck an emotional chord in many Americans, and decided on a campaign to persuade the voter that "sound money", the gold standard unless modified by international agreement, was much preferable to bimetallism. Such propaganda would not be cheap, as before the age of television and radio, the most effective way of reaching the electorate was through the written word, and through public speakers who would address meetings on behalf of the candidate. This would take money, and Hanna undertook to secure it from his corporate connections.[61] As Hanna began his fundraising efforts in late July, the Populists met in St. Louis. Faced with splitting the silver vote, they chose to endorse Bryan, beginning their dissolution as a party.[62]

Large sums had to be spent quickly, and Hanna energetically built a businesslike campaign. Bryan's surge contributed to a sense of crisis that enabled Hanna to make peace in his party, eventually uniting all behind McKinley with the exception of some Silver Republicans. But as the campaign began operations, and began them on a huge scale, money was short.[63] Hanna initially spent much of his time in New York, where many financiers were based. He faced resistance at first, both because he was not yet widely known on the national scene, and because some moneymen, although appalled at the Democratic position on the currency issue, felt Bryan was so extreme that McKinley was sure to win. Others were disappointed New York Governor Morton was not the presidential nominee, but their support became warmer as they came to know McKinley and Hanna. Reports of Bryan support in the crucial Midwest, and intervention by Hanna's old schoolmate, John D. Rockefeller (his Standard Oil gave $250,000), made executives more willing to listen. After a gloomy August for the campaign's fundraising, in September, corporate moguls "opened their purse strings to Hanna".[64] J. P. Morgan gave $250,000. Dawes recorded an official figure for fundraising of $3,570,397.13, twice what the Republicans had raised in 1892, and as much as ten times what Bryan may have had to spend.[65] Dawes' figure did not include fundraising by state and local committees, nor in-kind donations such as railroad fare discounts, which were heavily subsidized for Republican political travelers, including the delegations going to see McKinley. Estimates of what Republicans may have raised in total have ranged as high as $16.5 million.[66]

From his house on North Market Street in Canton, McKinley ran his campaign, with telephone and telegraph at his disposal. Hanna was busy meeting with executives to extract funds, and delegated much of the day-to-day policymaking to others, most prominently Dawes, who was a member of the campaign executive committee and was responsible for distributing much of the money that Hanna raised. Payne was nominally in charge of the Chicago office, but Dawes, a member of the McKinley inner circle, had more influence. Pamphlets were sent from Chicago in carload lots across the country. The campaign spent almost $500,000 on printing alone, which Stanley Jones, in his account of the 1896 campaign, estimated paid for hundreds of millions of pamphlets.[67] The campaign paid for hundreds of speakers to stump on McKinley's behalf.[68] Efforts were made to keep expenses down; Dawes insisted on competitive bidding,[69] and most of his top-level hires were business associates, not political operatives. Others prominent in the Chicago office included Charles Dick, the secretary of the organization and later a senator.[70]

Front porch campaign

We know what partial free trade has done for the labor of the United States. It has diminished its employment and earnings. We do not propose now to inaugurate a currency system that will cheat labor in its pay. The laboring men of this country whenever they give one day's work to their employers, want to be paid in full dollars good anywhere in the world ... We want in this country good work, good wages, and good money.

William McKinley, address to a delegation of Pennsylvania ironworkers, September 19, 1896.[71]

From the moment he was nominated, McKinley was beset by supporters coming to Canton to hail him, hoping to hear him give a political speech. McKinley remained in Canton, available to the public every day but Sunday, continuously from his June nomination until Election Day in November, excepting one trip in July to give previously arranged nonpolitical speeches in Cleveland and at Mount Union College. He also took one weekend of rest in late August.[72] The need to greet and speak to supporters made it difficult for McKinley to get campaign work done; one political club interrupted his conference with Hobart in late June. McKinley complained that his time was not being well managed.[73]

Bryan's announcement, after gaining the Democratic nomination, that he would undertake a nationwide tour by rail, something then unusual for presidential candidates, put pressure on McKinley to match him. Hanna especially urged his candidate to hit the road. McKinley decided against this, feeling that he could not outdo Bryan, who was a brilliant stump speaker, and that he would be foolish to try. "I might as well put up a trapeze on my front lawn and compete against some professional athlete as go out speaking against Bryan. I have to think when I speak."[74] Furthermore, no matter how McKinley traveled, Bryan would upstage him by choosing a less comfortable manner. McKinley was unwilling to compete with Bryan on the Democrat's terms, and sought to find his own way to reach the people.[75]

The front porch campaign that McKinley decided on was a natural extension of the pilgrimages to Canton by McKinley devotees that were already occurring. After a few initial stumbles, things settled into routine by mid-September. While any group could visit McKinley by writing in advance,[75] his campaign arranged for many of them, and they came from towns small and large.[76] If possible, the group's leader was brought to Canton in advance to confer with McKinley on what each would say; if not, the group would be met at the Canton railroad station by a McKinley representative, who would discuss what would be said with the group's leader. There were parades every day in Canton that campaign season, as the groups marched through the bunting-draped streets, escorted by a mounted troop known as the McKinley Home Guards, who saw to it that groups arrived at the McKinley residence on a prearranged schedule. There, the group leader would deliver his remarks, and McKinley would deliver a reply often prepared in advance. Afterwards, there might be refreshments or the opportunity to shake hands with McKinley, before the delegation was escorted off for their return journey to the railroad station. If it rained, the meetings took place in one of several indoor venues.[77]

Bicycling was the latest craze in the United States in 1896, and among those who came to salute McKinley was a brigade of bicyclists, who pulled images of McKinley and Hobart behind their vehicles, and performed tricks as they went to see their presidential candidate.[78] The people of Canton joined in enthusiastically, and restaurants and souvenir venders expanded their operations. A popular source of keepsakes was the wood of McKinley's front porch or fence, whittled as supporters listened, and the blades of his lawn, when not trampled underfoot, made later appearances in scrapbooks. In between delegations, McKinley entertained visitors; future Secretary of State John Hay, a major backer, came to Canton reluctantly, not relishing the crowds, but wrote "he met me at the [railroad] station, gave me meat & took me upstairs and talked for two hours as calmly & serenely as if we were summer boarders in Bethlehem, at a loss for means to kill time. I was more struck than ever with his mask. It is a genuine Italian ecclesiastical face of the XVth Century."[79]

With his campaign ill-financed, Bryan was his own greatest asset, and traveled to 27 of the 45 states, logging 18,000 miles (29,000 km), and in his estimated 600 speeches reached some 5,000,000 listeners.[80] McKinley did not match those numbers, speaking 300 times to 750,000 visitors, but in remaining at home, he avoided the fatigue of Bryan's exhausting tour. The Republican was better able to provide fresh material for the next day's newspapers without making gaffes; Bryan made several. According to R. Hal Williams in his book on the 1896 campaign, "The Front Porch Campaign was a remarkable success."[81]

Issues and tactics

Bryan's nomination caused defections and divisions in the Republican party; many farmers in the Midwest, even in McKinley's Ohio, found the inflation it was expected free silver would cause to be attractive, as it would make it easier to repay debts. Polls in battleground midwestern states, and word from activists there, showed that Bryan had made deep inroads into Republican support. One survey in August showed that of the midwestern states, only Wisconsin was safe for the Republicans.[82]

By early in August, the McKinley campaign had decided upon a strategy: appeal to labor and established farmers.[83] McKinley, on the urgent advice of his advisers, by the middle of that month had decided that the currency question must be addressed immediately, and the campaign machine began the process of generating millions of publications and sending hundreds of speakers into the field. The pamphlets contained quotes or articles from McKinley, members of Congress, and financial experts on why a bimetallic standard would be ruinous to the country.[84] Theodore Roosevelt, then a member of the New York City Police Commission, recalled seeing boxcars full of paper being dispatched when he visited the Chicago headquarters in August.[85] For the benefit of those who did not read English, there were pamphlets in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Yiddish, German, Polish, Norwegian, Italian, Danish, and Dutch. Pre-written articles were sent to periodicals, and the campaign paid for friendly newspapers to be sent to thousands of citizens across the country for the duration.[84] Five million families received McKinley campaign materials on a weekly basis.[86] Among the surrogates sent out on McKinley's behalf was newspaper editor Warren G. Harding, paid to make speeches across Ohio. The future president made a positive impression and three years later was elected to the Ohio State Senate, beginning his political rise.[87]

On his front porch, McKinley urged sound money, though he never ceased to promote protectionism to support American industry. Horner noted, "the campaign effectively linked both gold and protectionism with patriotism."[88] McKinley felt that he could not campaign entirely on the money issue, as many midwestern Republicans who supported silver considered protection the major issue of the campaign, and would stay with the party if it promoted tariffs.[71] These issues were given different emphases sectionally: in the East and South, the money issue was stressed most strongly, while tariffs were given more attention in the Midwest. McKinley had little support in the mining-dominated Rocky Mountain states, where even most Republicans were for silver and Bryan. On the Pacific coast, where there was strong silver sentiment, but where McKinley had some hope of winning, the tariff was made the major issue.[89]

McKinley soothed ruffled feathers of party bigwigs by mail and in person. Though former president Harrison refused to tour, he gave a speech in New York where he railed against free silver, stating, "the first dirty errand that a dirty dollar does is to cheat the workingman".[90] The public was closely following the campaign, and the Republican efforts had their effect. In September, polls showed the midwestern states leaning Republican, though silver-supporting Iowa was still close.[91] McKinley's running mate, Hobart, continued to look after his law practice and business interests, and was apparently a major contributor to the Republican campaign. He helped to run the New York office, gave some speeches from his own front porch in Paterson, and in October went on a short campaign tour of New Jersey, though he was a reluctant public speaker. Hobart was much stronger for the gold standard than was McKinley, and made clear his views in his speeches.[92]

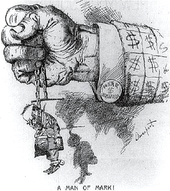

William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal was hostile to McKinley throughout the campaign; prior to the Republican convention, Alfred Henry Lewis accused Hanna of acting on behalf of a syndicate, controlling McKinley.[93] During the general election campaign, the Democratic newspapers, especially the papers owned by Hearst, attacked Hanna for his supposed role as McKinley's political master. These articles and cartoons have contributed to a lasting popular belief that McKinley was not his own man, but that he was effectively owned by the corporations, through Hanna. Homer Davenport's cartoons for the Hearst papers were especially effective in molding public opinion about Hanna, who was often depicted as "Dollar Mark", in a suit decorated with dollar signs (a term for which "dollar mark" was a common alternative). McKinley's 1893 personal financial crisis allowed him to be convincingly depicted as a child, helpless in the hands of businessmen and their mere tool in the 1896 campaign.[94] Hearst and the Journal gave $41,000 to Bryan's campaign, one of the largest the Democrats received, but that amount was dwarfed by the sums raised by Hanna.[95]

September saw Maine and Vermont go heavily Republican in their state elections, meaning the Northeast was likely safe for McKinley. Early in that month, dissident Democrats, who favored the gold standard and President Cleveland's policies, formed the National Democratic Party, or Gold Democrats, meeting in Indianapolis. The nomination of Illinois Senator John M. Palmer for president and former Kentucky governor Simon Bolivar Buckner for vice president meant Bryan would have to overcome an electoral split in his party.[96] Hanna applauded the selection, and predicted it would get large numbers of votes.[97] There was no chance Palmer would win the election, and Hanna saw to it that the Gold Democrats were aided with quietly-provided funds.[96]

The Midwest was the crucial battleground, and both parties poured in their resources, with Bryan spending most of his time there, as did Hanna. McKinley and Hanna began to sense that the flood of materials and speakers on the silver question had had their effect in the Midwest. Dawes began to slow the flow of pamphlets against silver, and set loose a flood of material favoring McKinley's tariff policies.[98][99] Events favored the Republicans: wheat prices rose considerably in the final weeks of the campaign, lessening the enthusiasm of farmers for free silver.[100] The Democrats alleged that Republicans were coercing workers into voting for McKinley on threat of losing their jobs; Hanna denied it, and offered a reward for evidence, that was not claimed.[101] To Bryan's outrage, Hanna called for a "Flag Day" for the final Saturday, October 31, as the campaign again sought to link support for McKinley to patriotism, a theme echoed by the candidate as he addressed his final delegations. Hundreds of thousands marched through the streets of the nation's cities in honor of the flag; New York City saw its largest parade since 1865. Election day was November 3; on its eve Hanna and Dawes predicted overwhelming victory.[100]

Election

Stanley Jones wrote of the 1896 campaign:

For the people it was a campaign of study and analysis, of exhortation and conviction—a campaign of search for economic and political truth. Pamphlets tumbled from the presses, to be snatched up eagerly, to be read, reread, studied, debated, to become guides to economic thought and political action. They were printed and distributed by the million, enough to provide several copies for every man, woman, and child in the country; but the people clamored for more. Favorite pamphlets became dog-eared, grimy, fell apart as their owners laboriously restudied their arguments and quoted from them in public and private debate.[102]

Voters cast their ballots on November 3, and that evening gathered in cities and around telegraph offices. In places like New York, the results were projected by stereopticon onto the sides of newspaper buildings. The election was considered by many to be the most crucial since 1860, and large numbers of voters followed the returns all night. McKinley cast his ballot early, going with his brother Abner to the polling place, and met Hanna for lunch. That evening, McKinley sat in his library as the returns came in by telegraph. It was quickly apparent that McKinley was leading, and by midnight he had pencilled the figure "241" on a pad, the number of electoral votes of states that were certain, enough for victory.[103][104] Hanna wired from Cleveland to Canton, "The feeling here beggars description ... I will not attempt bulletins. You are elected to the highest office of the land by a people who always loved and trusted you."[105]

McKinley won the entire Northeast and Midwest, and broke into the border states to win Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and West Virginia. He won North Dakota, and came close in South Dakota, Kansas, and in Bryan's Nebraska. McKinley was also successful in California and Oregon.[106][107] McKinley won with 7.1 million votes to Bryan's 6.5 million, 51% to 47%. The electoral vote was not as close: 271 for McKinley to 176 for Bryan.[108] McKinley increased the Republican vote by 2,000,000 from Harrison's defeat in 1892, though Bryan also increased the Democratic total.[109]

Bryan had hoped to sweep the rural vote and make inroads on urban labor, but he was not successful. McKinley became the first Republican candidate to win in New York City, and won in its rival city of Brooklyn as well. He lost only one city with a population of over 45,000 in the Midwest, and won many rural counties in crucial states. Although Bryan won all states south of Kentucky and from Texas east, McKinley won most urban centers there.[107]

Election day. Went after dinner to vote for Wm. McKinley

John A. Sanborn, farmer, Franklin, Nebraska. Diary entry for November 3, 1896.[110]

Irish immigrants generally remained loyal to the Democratic Party, but McKinley's promises of sound money attracted German-Americans who were appalled by Bryan's inflationary proposals. German-Americans had long been Democratic; efforts by that party to rebut McKinley, including circulating a statement by Bismarck in support of bimetallism, were ineffective. Many Catholics and recent immigrants favored McKinley because of the dislike the American Protective Association had for him.[111]

Appraisal

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Karl Rove saw several reasons for McKinley's triumph. McKinley campaigned on big issues, the tariff and sound money. The candidate went after Bryan's strongest issue, silver, arguing that bimetallism would harm Americans and hit the working class hardest. McKinley's theme was that it was morally wrong to debase the currency; he linked his stand for sound money with the tariff and with patriotism, appealing to crucial voter blocs who gave McKinley the biggest victory in a presidential election since Grant in 1872. He reached out to immigrants and urban factory workers, recognizing their importance in a changing America. And to implement these strategies, McKinley, with Hanna's aid, created a larger, more organized campaign structure than had previously been seen in presidential campaigns.[113]

Jones noted, "The Republican Party, under the skillful leadership of McKinley and Hanna, produced a combination of votes which gave it the victory in 1896 and which promised Republican ascendency for many years in the future."[114] The 1896 presidential race is often considered a realigning election, when there is a major shift in voting patterns, upsetting the political balance. McKinley was supported by middle-class and wealthy voters, urban laborers, and prosperous farmers; this coalition would keep the Republicans mostly in power until the 1930s.[115] McKinley's wooing of the Midwest would pay ample dividends in the years to come, as it remained solidly Republican in most years until 1932.[116]

Williams suggested that McKinley's campaign of education of the voter through speakers and literature brought him victory, but with a cost to the close identification between voters and the political parties that was typical in the 19th century. Voter turnout was almost 80 percent in 1896, about average for presidential elections in the late 19th century, but then dropped substantially and remained at lower levels as voters, who once participated in rallies and torchlight processions for candidates, were distracted by radio and by professional sports. Nevertheless, later campaigns tried to recapture the magic of 1896; Warren G. Harding conducted his own front porch campaign in 1920, even borrowing the flagpole from McKinley's old front yard.[117]

William D. Harpine, studying McKinley's rhetoric during the front porch campaign, argued that McKinley's campaign was in some ways ahead of its time, "even in the age of broadcasting, most candidates for nationwide office embark on a campaign tour. In 1896, long before the advent of broadcasting, McKinley accomplished the same purpose as a modem candidate, and did so without making a campaign tour."[118] The visits of the delegations to the McKinley home in Canton constituted a series of media events that McKinley used to get his speeches into the newspapers.[118] In speaking from his front porch, McKinley was not principally addressing the delegations, but the many Americans who would not visit Canton, and who would read the speeches in newspapers.[119] Williams agreed, "the remarkable Front Porch Campaign used modern technology to bring 750,000 visitors to his small hometown and dispatched his message nationwide."[120]

Rove, while an advisor to Texas Governor George W. Bush during the 2000 election campaign, often spoke of the parallels he saw between McKinley and his 1896 campaign, and the 2000 election, going so far as to fax copies of books on McKinley. The media took the parallels further than Rove intended, making comparisons between him and Hanna, hinting that Rove controlled Bush like it was said Hanna controlled McKinley.[121] Williams also saw the lasting effect of McKinley's 1896 campaign, "a new approach to campaigning, the educational or merchandising style, continues to mold campaigns today, as does McKinley's focus on message, Hanna's use of money, and Dawes's reliance on efficiency and education ... more than a century later, Americans and their political leaders can still learn from the events of the 1890s, whose lessons echo down the years today."[122]

Harpine saw McKinley's personal touch as key to his successful race:

McKinley created the impression that he was, in the fashion of pre-Civil War candidates, waiting casually at home for the people to elect him. Yet, McKinley during the summer of 1896 initiated a vigorous, carefully crafted campaign that employed all of the resources available to him to reach and persuade the national voting public ... There was something folksy about campaigning so casually from a modest, middle-class home. When the throngs of voters stepped off the train in Canton, they discovered that McKinley was to all appearances one of them. It was in large part this quality, the ability to project warm personality through these groups to the press, that led to the success of the Front Porch campaign.[123]

Results

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| William McKinley | Republican | Ohio | 7,108,480 | 51.03% | 271 | Garret A. Hobart | New Jersey | 271 |

| William Jennings Bryan | Democratic – People's | Nebraska | 6,509,052(a) | 46.70% | 176 | Arthur Sewall(b) | Maine | 149 |

| Thomas E. Watson(c) | Georgia | 27 | ||||||

| John M. Palmer | National Democratic | Illinois | 133,537 | 0.96% | 0 | Simon Bolivar Buckner | Kentucky | 0 |

| Joshua Levering | Prohibition | Maryland | 124,896 | 0.90% | 0 | Hale Johnson | Illinois | 0 |

| Charles Matchett | Socialist Labor | New York | 36,359 | 0.26% | 0 | Matthew Maguire | New Jersey | 0 |

| Charles Eugene Bentley | National Prohibition | Nebraska | 19,367 | 0.14% | 0 | James Southgate | North Carolina | 0 |

| Other | 1,570 | 0.01% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 13,936,957 | 100% | 447 | 447 | ||||

| Needed to win | 224 | 224 | ||||||

(a) Includes 222,583 votes as the People's nominee.

(b) Sewall was Bryan's Democratic running mate.

(c) Watson was Bryan's People's running mate.[124]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Until 1913, state legislatures elected senators.

- ^ Although at the time, no state conducted a primary election for president.

- ^ Formally, the Committee on Resolutions, and chaired by Senator-elect Foraker.

- ^ There was also a New York headquarters, run by McKinley's cousin William M. Osborne, along with Hobart and Quay. It was responsible for sending literature to the East and South, which were not expected to be important in the election. See Rove, pp. 240–241, Connolly, p. 27, Jones, pp. 278–279, 295

References

- ^ Horner, p. 169.

- ^ Gould, Louis L. (February 2000). "McKinley, William". American National Biography. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ Dean, p. 58.

- ^ Rove, p. 7.

- ^ Phillips, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Rove, pp. 69–75.

- ^ Rove, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Horner, p. 194.

- ^ Rove, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Horner, p. 85.

- ^ Rove, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Horner, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Morgan 1969, p. 125.

- ^ Horner, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Morgan 1969, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Williams, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Phillips, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Morgan 1969, pp. 129–134.

- ^ Horner, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Phillips, p. 68.

- ^ Leech, p. 60.

- ^ Williams, p. 39.

- ^ Jones, pp. 6–13.

- ^ Williams, pp. 27–35.

- ^ Jones, p. 46.

- ^ Rove, pp. 141–144.

- ^ Leech, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Williams, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Jones, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Rove, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Croly, pp. 173–176.

- ^ Rove, pp. 110–115.

- ^ Horner, p. 142.

- ^ a b Williams, p. 57.

- ^ Walters, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Jones, p. 109.

- ^ Horner, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Rove, pp. 116–121.

- ^ Jones, pp. 114–118.

- ^ Leech, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Jones, p. 103.

- ^ Jones, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Rove, pp. 163–166.

- ^ Horner, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Rove, pp. 215–221.

- ^ Rove, pp. 227–233.

- ^ Jones, p. 161.

- ^ Jones, pp. 162–173.

- ^ Leech, pp. 81–83.

- ^ a b Croly, p. 191.

- ^ Jones, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b Hatfield, p. 290.

- ^ Rove, pp. 240–242.

- ^ a b Rhodes, p. 19.

- ^ Rove, pp. 248–252.

- ^ Coletta, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b c Phillips, p. 74.

- ^ Coletta, p. 143.

- ^ Horner, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Williams, p. 129.

- ^ Horner, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Jones, pp. 244, 262.

- ^ Morgan 1969, pp. 508–509.

- ^ Horner, pp. 186–191, 210.

- ^ Williams, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Horner, pp. 193–200.

- ^ Jones, pp. 276–279.

- ^ Morgan 1969, pp. 516–517.

- ^ Jones, p. 279.

- ^ Williams, p. 194.

- ^ a b Jones, p. 287.

- ^ Leech, p. 87.

- ^ Rove, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Williams, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Williams, p. 131.

- ^ Jones, p. 283.

- ^ Rove, pp. 311–315.

- ^ Horner, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Taliaferro, p. 307.

- ^ Morgan 1969, pp. 515–516.

- ^ Williams, p. 134.

- ^ Williams, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Morgan 1969, p. 508.

- ^ a b Horner, p. 202.

- ^ Rove, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Morgan 1969, p. 509.

- ^ Dean, p. 23.

- ^ Horner, p. 204.

- ^ Jones, pp. 281–288.

- ^ Morgan 1969, p. 510.

- ^ Phillips, p. 75.

- ^ Connolly, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Jones, p. 177.

- ^ Horner, p. 127.

- ^ Williams, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Williams, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Rove, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Williams, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Rove, pp. 331–332.

- ^ a b Williams, pp. 142–145.

- ^ Rove, pp. 349–351.

- ^ Jones, p. 332.

- ^ Morgan 1969, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Williams, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Morgan 2003, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Morgan 1969, p. 521.

- ^ a b Williams, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Morgan 1969, p. 522.

- ^ Jones, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Williams, p. 149.

- ^ Jones, pp. 345–346.

- ^ "After Words with Karl Rove". C-SPAN. January 2, 2016. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- ^ Rove, pp. 365–369.

- ^ Jones, p. 346.

- ^ Williams, pp. xi, 152–153.

- ^ Jones, pp. 347–348.

- ^ Williams, pp. 168–170.

- ^ a b Harpine, p. 74.

- ^ Harpine, p. 85.

- ^ Williams, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Horner, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Williams, p. 171.

- ^ Harpine, p. 87.

- ^ Source: National Archives, USA Election Atlas

Bibliography

Books

- Coletta, Paulo E. (1964). William Jennings Bryan: Political Evangelist, 1860–1908. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0022-7.

- Croly, Herbert (1912). Marcus Alonzo Hanna: His Life and Work. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 715683. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- Dean, John W. (2004). Warren Harding (Kindle ed.). Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-6956-3.

- Hatfield, Mark O. (1997). Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993 (PDF). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-0968-6.

- Horner, William T. (2010). Ohio's Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man and Myth. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1894-9.

- Jones, Stanley L. (1964). The Presidential Election of 1896. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. OCLC 445683.

- Leech, Margaret (1959). In the Days of McKinley. New York: Harper and Brothers. OCLC 456809.

- Morgan, H. Wayne (1969). From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2136-2.

- Morgan, H. Wayne (2003). William McKinley and His America (revised ed.). Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-765-1.

- Phillips, Kevin (2003). William McKinley. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6953-2.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1922). The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897–1909. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 457006.

- Rove, Karl (2015). The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-5295-2.

- Taliaferro, John (2013). All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt (Kindle ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9741-4.

- Walters, Everett (1948). Joseph Benson Foraker: An Uncompromising Republican. Columbus, OH: The Ohio History Press. OCLC 477641.

- Williams, R. Hal (2010). Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan and the Remarkable Election of 1896. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1721-0.

Journals

- Connolly, Michael J. (2010). "'I Make Politics My Recreation': Vice President Garret A. Hobart and Nineteenth Century Republican Business Politics". New Jersey History. 125 (1): 20–39. doi:10.14713/njh.v125i1.1019.

- Harpine, William D. (Summer 2000). "Playing to the Press in McKinley's Front Porch Campaign: The Early Weeks of a Nineteenth-Century Pseudo-Event". Rhetorical Studies Quarterly. 30 (3): 73–90. doi:10.1080/02773940009391183. JSTOR 3886055. S2CID 143880262.