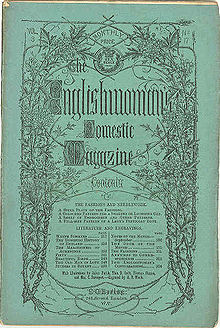

The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine

The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (EDM) was a monthly magazine which was published between 1852[1] and 1879.[2] Initially, the periodical was jointly edited by Isabella Mary Beeton and her husband Samuel Orchart Beeton, with Isabella contributing to sections on domestic management, fashion, embroidery and even translations of French novels.[3] Some of her contributions were later collected to form her widely acclaimed Book of Household Management.[4] The editors sought to inform as well as entertain their readers; providing the advice of an 'encouraging friend' and 'cultivation of the mind'[5] alongside serialised fiction, short stories and poetry. More unusually, it also featured patterns for dressmaking.

Originally priced at 2d, the periodical was a relatively cheap option for young, middle-class women. In 1860, however, following the Paper Tax abolition, the Beeton's decided to take the publication in a slightly different direction; opting to relaunch in a larger format and include high quality coloured plates.[6] Subsequently, the price of the magazine rose to 6d.

In 1865, following the death of Isabella Beeton, the magazine was co-edited by her friend, Matilda Brown.

In 1867, Beeton expanded the existing correspondence section of the magazine. The contents of this "Conversazione", now included contributions by men, included material extolling the attractions of corsetry[7]/tight-lacing, cross-dressing[8] and flagellation;[9] extracts on the latter were republished in pornographic compilations such as The Birchen Bouquet.[10]

Social importance

Through their correspondence columns and the subjects of their serialised fiction, The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine provided a platform for middle-class women to express and confront the anxieties of femininity and domesticity.[11] It was also a valuable resource for fashion, being 'the first English serial to make dress patterns and the latest fashions available to a mass audience'.[12]

The magazine was considered an essential tool for any Victorian woman looking to fit into society and keep up with the times, especially in terms of fashion. Beeton later published other journals, some specifically on Victorian fashion. Le Moniteur de la Mode and The Queen appeared in 1861. They emphasized what was already featured in the EDM.[13] The magazine was a way for readers to write in and explain their own lives and problem remedies. It could be used as an encyclopedia, a correspondence between readers, and a place for women to share their thoughts on everyday issues.

Corsets

Corsets and tight-lacing were extensively explored by EDM. Tight-lacing was used as a way to enhance a women's figure, as it gradually added pressure on her waist to make it smaller over time. Some women slept in their corsets in hopes of tying it tighter in the morning. EDM had a correspondence column called, “The Corset Correspondence”. Two columns “Cupids Letter-Bag” and “Englishwoman’s Conversazione” were later combined into “The Conversazione””.[14] The editors “decided to create some detached volumes about the themes due to the profit that this topic brought in. The Corset and the Crinoline (later republished as The Freaks of Fashion) and a History of the Rod”.[14]

EDM became a source of information for Victorian women. It sparked controversy, especially in terms of fashion and the pressures it put on women to look a certain way in a society obsessed with appearance. Corsets became the rage. Young girls, sometimes under the age of ten, were forced to tighten their waists before puberty. For instance, “The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine of September 1872 included a pattern and sketch for a garment called baby stays, which were not boned but could be tied tightly”.[15] “L. Thompson, a correspondent in the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, not only recommended putting young girls in stays at an early age, but suggested that it was actually the common practice: ”It is seldom that girls are allowed to attain the age of fourteen or fifteen before commencing stays. The great secret is to begin their use as early as possible, and no…severe compression will be requisite. It seems absurd to allow the waist to grow large and clumsy, and then reduce it again to more elegant proportions by means which must at first be more less productive of inconvenience””.[15] The idea was to direct body growth to minimize the possibility of an unfashionable figure.

Corseting girls and the health (mental and physical) problems it could create was a frequent discussion point. “In 1867 an innocent letter from a mother worried about the use of corsets in her daughter’s school sparked a long discussion, in which the connection between tight-lacing, torture and pleasure was made explicit. Right when the “corset correspondence” ended, a more sadistic subject rose, concerning the habit of whipping to control female servants and girls”.[14] Furthermore, “a letter, which started the long discussion of tight-lacing, came from a mother complaining that she had left her “merry, romping girl” in a “large and fashionable boarding school near London” when she went abroad. On her return four years later she saw a “tall pale young lady glide slowly in with measured gait and languidly embrace me”; her absurdly small waist explained her change in demeanor”.[15]

References

- ^ Margaret Beetham (2004). "Beeton, Samuel Orchart (1831-1877)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Albert Johannsen (1950). "Beeton, Samuel Orchart". The House of Beadle & Adams and its Dime and Nickel Novels: The Story of a Vanished Literature. Vol. II. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 32–33.

- ^ "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ Beetham, Margaret; Boardman, Kay (2001). Victorian women's magazines: an anthology. Manchester University Press. pp. 32, 36. ISBN 978-0-7190-5879-0.

- ^ "Our Address". The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine. 1 (1): 1. 1852 – via Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals.

- ^ Onslow, Barbara (2000). Women of the press in nineteenth-century Britain. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23602-6. OCLC 44075916.

- ^ Margaret Beetham (1991). "'Natural but firm': the corset correspondence in the Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine". Women: A Cultural Review. 2 (2): 163–167. doi:10.1080/09574049108578076.

- ^ Ekins, Richard; King, Dave (1996). Blending genders: social aspects of cross-dressing and sex-changing. Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-415-11552-0.

- ^ Marcus 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Kathryn Hughes (2001). The Victorian governess. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-85285-325-9.

- ^ Beetham, Margaret (1996). A magazine of her own? : domesticity and desire in the woman's magazine, 1800-1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04920-2. OCLC 33244682.

- ^ "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ Diamond, Marion (1997). "Maria Rye and "The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine"". Victorian Periodicals Review. 30: 5–16. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Moja, Beatrice. "The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine: a Victorian Fashion Guide Edited by the Famous Mrs Beeton". Academia. Liverpool J. Moores University. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Helene E. (1977). "The Exquisite Slave: The Role of Clothes in the Making of the Victorian Woman". Signs. 2 (3): 554–569. doi:10.1086/493387. JSTOR 3173265.

Sources

- The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, 1852-1879. Curated chronological listing of open-access copies of The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, including those available at Google Books, the Hathi Trust, and the Internet Archive.

- Marcus, Sharon (2007). Between Women Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England. ISBN 9780691128351. OCLC 1020172224.