The Battle of Algiers

| The Battle of Algiers | |

|---|---|

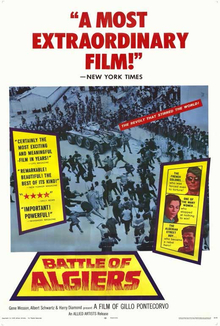

U.S. theatrical release poster | |

| Italian: La battaglia di Algeri Arabic: Maʿrakat al-Jazāʾir | |

| Directed by | Gillo Pontecorvo |

| Written by | Franco Solinas |

| Story by | Franco Solinas Gillo Pontecorvo |

| Based on | Souvenirs de la Bataille d'Alger by Saadi Yacef |

| Produced by | Antonio Musu Saadi Yacef |

| Starring | Jean Martin Saadi Yacef Brahim Haggiag Tommaso Neri |

| Cinematography | Marcello Gatti |

| Edited by | Mario Morra Mario Serandrei |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone Gillo Pontecorvo |

Production companies | Igor Film Casbah Film |

| Distributed by | Allied Artists (USA) |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Countries | Italy Algeria |

| Languages | Arabic French |

| Budget | $806,735 |

| Box office | $879,794 (domestic)[2] |

The Battle of Algiers (Italian: La battaglia di Algeri; Arabic: معركة الجزائر, romanized: Maʿrakat al-Jazāʾir) is a 1966 Italian-Algerian war film co-written and directed by Gillo Pontecorvo. It is based on action undertaken by rebels during the Algerian War (1954–1962) against the French government in North Africa, the most prominent being the eponymous Battle of Algiers, the capital of Algeria. It was shot on location in a Roberto Rossellini-inspired newsreel style: in black and white with documentary-type editing to add to its sense of historical authenticity, with mostly non-professional actors who had lived through the real battle. The film's score was composed by Pontecorvo and Ennio Morricone. It is often associated with Italian neorealist cinema.[3]

The film concentrates mainly on revolutionary fighter Ali La Pointe during the years between 1954 and 1957, when guerrilla fighters of the FLN went into Algiers. Their actions were met by French paratroopers attempting to regain territory. The highly dramatic film is about the organization of a guerrilla movement and the illegal methods, such as torture, used by the French to stop it. Algeria succeeded in gaining independence from the French, which Pontecorvo addresses in the film's epilogue.[4]

The film was met with international acclaim, and it's considered to be one of the greatest films of all time. It won the Golden Lion at the 27th Venice Film Festival among other awards and nominations. It also was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. A subject of sociopolitical controversy in France, the film was not screened in the country for five years.[1] Insurgent groups and state authorities have considered it to be an important commentary on urban guerrilla warfare. In Sight and Sound's 2022 poll of the greatest films of all time, it ranked 45th on the critics' list and 22nd with directors.

In 2008, the film was included on the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage’s 100 Italian films to be saved, a list of 100 films that "have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978."[5]

Subject

The Battle of Algiers reconstructs the events that occurred in the capital city of French Algeria between November 1954 and December 1957, during the Algerian War of Independence. The narrative begins with the organization of revolutionary cells in the Casbah. Because of partisan warfare between the Algerian locals and Pied-Noir, in which both sides commit acts of increasing violence, France sends French Army paratroopers to the city to fight against and capture members of the National Liberation Front (FLN). The paratroopers are depicted as neutralizing the whole of the FLN leadership through either assassination or capture. The film ends with a coda depicting nationalist demonstrations and riots, suggesting that although France won the Battle of Algiers, it lost the Algerian War.[4]

The tactics of the FLN guerrilla insurgency and the French counter insurgency, and the uglier incidents of the war are depicted. Both colonizer and colonized commit atrocities against civilians. The FLN commandeer the Casbah via summary execution of Algerian criminals and suspected French collaborators; they commit terrorism, including actions like the real-life Milk Bar Café bombing, to harass Europeans. The security forces resort to killings and indiscriminate violence against the opposition. French paratroops are depicted as routinely using torture, intimidation, and murder.[4]

Pontecorvo and Solinas created several protagonists in their screenplay who are based on historical war figures. The story begins and ends from the perspective of Ali la Pointe (Brahim Haggiag), a petty criminal who is politically radicalized while in prison. He is recruited by FLN commander El-hadi Jafar, played by Saadi Yacef, who was a veteran FLN commander.[6]

Lieutenant-Colonel Mathieu, the paratroop commander, is the principal French character. Other characters are the boy Petit Omar, a street urchin who is an FLN messenger; Larbi Ben M'hidi, a top FLN leader who provides the political rationale for the insurgency; and Djamila, Zohra, and Hassiba, three FLN women urban guerrillas who carry out a terrorist attack. The Battle of Algiers also features thousands of Algerian extras. Pontecorvo intended to have them portray the "Casbah-as-chorus", communicating with chanting, wailing, and physical effect.[3]

Production and style

Screenplay

The Battle of Algiers was inspired by the 1962 book Souvenirs de la Bataille d'Alger, an FLN military commander's account of the campaign, by Saadi Yacef.[7] Yacef wrote the book while he was held as a prisoner of the French, and it served to boost morale for the FLN and other militants. After independence, the French released Yacef, who became a leader in the new government. The Algerian government backed adapting Yacef's memoir as a film. Salash Baazi, an FLN leader who had been exiled by the French, approached Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo and screenwriter Franco Solinas with the project.[citation needed]

To meet the demands of film, The Battle of Algiers uses composite characters and changes the names of certain persons. For example, Colonel Mathieu is a composite of several French counterinsurgency officers, especially Jacques Massu.[8] Saadi Yacef has said that Mathieu was based more on Marcel Bigeard, although the character is also reminiscent of Roger Trinquier.[9] Accused of portraying Mathieu as too elegant and noble, screenwriter Solinas denied that this was his intention. He said in an interview that the Colonel is "elegant and cultured, because Western civilization is neither inelegant nor uncultured".[10]

Visual style

For The Battle of Algiers, Pontecorvo and cinematographer Marcello Gatti filmed in black and white and experimented with various techniques to give the film the look of newsreel and documentary film. The effect was so convincing that American releases carried a notice that "not one foot" of newsreel was used.[11]

Pontecorvo's use of fictional realism enables the movie "to operate along a double-bind as it consciously addresses different audiences." The film makes special use of television in order to link western audiences with images they are constantly faced with that are asserted to express the "truth". The film seems to be filmed through the point of view of a western reporter, as telephoto lenses and hand-held cameras are used, whilst "depicting the struggle from a 'safe' distance with French soldiers placed between the crowds and camera."[12]

Cast

Pontecorvo chose to cast non-professional Algerians. He chose people whom he met, picking them mainly on appearance and emotional effect (as a result, many of their lines were dubbed).[13] The sole professional actor of the movie was Jean Martin, who played Colonel Mathieu; Martin was a French actor who had worked primarily in theatre. Pontecorvo wanted a professional actor, but one who would not be familiar to most audiences, as this could have interfered with the movie's intended realism.[citation needed]

Martin had been dismissed several years earlier from the Théâtre National Populaire for signing the manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian War. Martin was a veteran; he had served in a paratroop regiment during the Indochina War and he had taken part in the French Resistance. His portrayal had autobiographical depth. According to an interview with screenwriter Franco Solinas, the working relationship between Martin and Pontecorvo was not always easy. Unsure whether Martin's professional acting style would contrast too much with the non-professionals, Pontecorvo argued about Martin's acting choices.[14]

Saadi Yacef, who plays El-Hadi Jaffar, and Samia Kerbash, who plays Fathia, were both members of the FLN and Pontecorvo is said to have been greatly inspired by their accounts. The actors credited are:

- Jean Martin as Colonel Philippe Mathieu

- Saadi Yacef as El-Hadi Jafar

- Brahim Haggiag as Ali La Pointe

- Tommaso Neri as Captain Dubois

- Samia Kerbash as Fathia

- Ugo Paletti as a Captain

- Fusia El Kader as Halima

- Franco Moruzzi as Mahmoud

- Mohamed Ben Kassen as Little Omar

Sound and music

Sound – both music and effects – perform important functions in the movie. Indigenous Algerian drumming, rather than dialogue, is heard during a scene in which female FLN militants prepare for bombings. In addition, Pontecorvo used the sounds of gunfire, helicopters and truck engines to symbolize the French methods of battle, while bomb blasts, ululation, wailing and chanting symbolize the Algerian methods. Gillo Pontecorvo wrote the music for The Battle of Algiers, but because he was classified as a "melodist-composer" in Italy, he was required to work with another composer as well; his good friend Ennio Morricone collaborated with him. The solo military drum, which is heard throughout the film, is played by the famous Italian drummer Pierino Munari.[15]

Release, reception and legacy

Initial reception

The film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for three Academy Awards (in non-consecutive years, a unique achievement): Best Foreign Language Film in 1966, and Best Screenplay (Gillo Pontecorvo and Franco Solinas) and Best Director (Gillo Pontecorvo) in 1968.[16] Other awards include the City of Venice Cinema Prize (1966), the International Critics Award (1966), the City of Imola Prize (1966), the Italian Silver Ribbon Prize (director, photography, producer), the Ajace Prize of the Cinema d'Essai (1967), the Italian Golden Asphodel (1966), Diosa de Plata at the Acapulco Film Festival (1966), the Golden Grolla (1966), the Riccione Prize (1966), Best Film of 1967 by Cuban critics (in a poll sponsored by Cuban magazine Cine), and the United Churches of America Prize (1967).

Given national divisions over the Algerian War, The Battle of Algiers generated considerable political controversy in France. It was one of the first films to directly confront the issue of French imperialism that reached the French Métropole; earlier films like Godard's Le petit soldat had only addressed such matters in passing.[17] Its initial festival screenings sparked nearly unanimous backlash among French critics. At the Venice Film Festival, the delegation of French journalists refused to attend the film's screening and abandoned the festival altogether when it received the Golden Lion.[18] Despite the high international acclaim, the national press and film industry united in opposition to the idea of releasing the film in French cinemas.[19]

The Battle of Algiers was formally banned by the French government for one year, though it did not see release in France for several more years because no private distributor would take the film.[18] Pontecorvo maintained that he had made a politically neutral film, contrary to the reaction of a French government that he described as "very sensitive on the Algerian issue," and he said "The Algerians put no obstacles in our way because they knew that I'd be making a more or less objective film about the subject."[20] In 1970 the film finally received a certificate for distribution in France, but release was further delayed until 1971 because of terroristic threats as well as civil opposition from veterans' groups.[19] The Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), a far-right paramilitary group, made bomb threats to theaters that sought to show the film.[18] Pontecorvo also received death threats.[17] Upon its release, reviews in the French press were generally much more favourable. Anti-censorship advocates came to the film's defense, and many critics reevaluated the film in light of the country's recent protest movements.[19] Most French audiences found its portrayal of the conflict to be nuanced and balanced, and the only disruption occurred in Lyons when an attendant threw ink at the screen.[18] Also, The international version of the film was shortened with torture scenes cut for British and American theaters.[1]

In the United States, the response to the film was altogether and immediately more positive than it had been in France.[18] The film achieved a surprising degree of popular success at the American box office, stoked by anti-war sentiments amid the movement against military involvement in Vietnam.[21] In a review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert called it a "great film" that "may be a deeper film experience than many audiences can withstand: too cynical, too true, too cruel and too heartbreaking. It is about the Algerian war, but those not interested in Algeria may substitute another war; The Battle of Algiers has a universal frame of reference."[22] Robert Sitton at The Washington Post called the film "One of the most beautiful I have ever seen" and said it "is just as important for our times as the works of Griffith, Leni Riefenstahl, Carl Dreyer and Luchino Visconti were for theirs."[18] Pauline Kael championed the film in The New Yorker, writing: "The burning passion of Pontecorvo acts directly on your emotions. He is the most dangerous kind of Marxist: a Marxist poet."[18]

Retrospective appraisal and influence

On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 99% based on 93 reviews, with an average rating of 9.10/10; the site's consensus reads: "A powerful, documentary-like examination of the response to an occupying force, The Battle of Algiers hasn't aged a bit since its release in 1966."[23] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 96 out of 100—indicating "universal acclaim"—based on 22 reviews collected since its 2004 re-release.[24]

By the time of the film's 2004 re-release, French reception was much more positive, with most critics accepting the film's aesthetic merits and historic significance as a given. A review in Libération deemed it the "best film ever made about the Algerian war" because it had been "the most credible and the fairest". A notable dissent came from Cahiers du Cinéma, which devoted a special feature to the film comprising five articles by various authors; the magazine's collective editorial denouncement of the film was "cast in such strong terms that it undermined, on moral grounds, the legitimacy of any critic or analyst who did not condemn the film, let alone anyone who dared consider it worthy of filmic attention," though ultimately their disapproval exerted little influence upon the broader French media.[19]

Roger Ebert added the film to his "Great Movies" series in 2004.[21] The film occupied the 48th place on the Critics' Top 250 Films of Sight and Sound's 2012 poll of the greatest films of all time,[25] as well as 120th place on Empire magazine's list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[26] In 2010, Empire ranked the movie 6th in its list of the 100 Best Films of World Cinema.[27] It was selected to enter the list of the "100 Italian films to be saved". In 2007, the film was ranked fifth in The Guardian's readers' poll listing the 40 greatest foreign films of all time.[28]

The Battle of Algiers has influenced numerous filmmakers. The American film director Stanley Kubrick praised the film's artistry in an interview with the French magazine Positif: "All films are, in a sense, false documentaries. One tries to approach reality as much as possible, only it's not reality. There are people who do very clever things, which have completely fascinated and fooled me. For example, The Battle of Algiers. It's very impressive."[29] Also, according to Anthony Frewin, Kubrick's personal assistant, he stated: "When I started work for Stanley in September 1965 he told me that I couldn't really understand what cinema was capable of without seeing The Battle of Algiers. He was still enthusing about it prior to his death."[29] The Greek-French political filmmaker Costa-Gavras cited the film as an influence on his filmmaking.[30] The American filmmaker Steven Soderbergh took inspiration from the film while directing the drug war drama Traffic, noting that it (along with Costa-Gavras's Z) had "that great feeling of things that are caught, instead of staged, which is what we were after."[31][32][33] The German filmmaker Werner Herzog admired the film and made it one of the few films designated as required viewing to his film school students.[34][35] The English filmmaker Ken Loach, who saw the film in 1966, listed it among his top 10 favorite films of all time and mentioned its influence on his work: "It used non-professional actors. It was not over-dramatic. It was low key. It showed the impact of colonialism on daily lives. These techniques had an important influence on my filmmaking."[36] The American actor and filmmaker Ben Affleck said The Battle of Algiers was a key influence on his film Argo (2012).[37] The British-American filmmaker Christopher Nolan has named the film as one of his favorites and has credited it as an influence on his films The Dark Knight Rises (2012) and Dunkirk.[38][39]

The film has also received praise from political commentators. The Palestinian-American academic Edward Said (famous for his work Orientalism) praised The Battle of Algiers (along with Pontecorvo's other film, Burn!) as the two films "stand unmatched and unexcelled since they were made in the 60s. Both films together constitute a political and aesthetic standard never again equaled."[40] The British-Pakistani writer and activist Tariq Ali placed The Battle of Algiers in his top 10 films list for the 2012 Sight and Sound poll.[41] In 2023, the progressive American magazine The New Republic ranked it first place on its list of the 100 most significant political films of all time.[42]

The Battle of Algiers and guerrilla movements

The release of The Battle of Algiers coincided with the decolonization period and national liberation wars, as well as a rising tide of left-wing radicalism in European nations in which a large minority showed interest in armed struggle. Beginning in the late 1960s, The Battle of Algiers gained a reputation for inspiring political violence; in particular, the tactics of urban guerrilla warfare and terrorism in the movie supposedly were copied by the Black Panthers, the Provisional Irish Republican Army, the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front.[43] The Battle of Algiers was apparently Andreas Baader's favourite movie.[44]

Pontecorvo, hearing that the journalist Jimmy Breslin had characterized The Battle of Algiers as a guerrilla warfare training film on American television, replied:

Perhaps he is right, but that is much too simple. The film champions everyone who is deprived of his rights, and encourages him to fight for them. But it is an analogy for many situations: Vietnam, for one. What I would prefer for people to discover is something that is in all my films, a certain kind of tenderness for man, an affection which grows from the fragility of the human condition.[45]

Later Screenings

Screenings for counterinsurgency agencies

1960s screenings in Argentina

President Arturo Frondizi (Radical Civic Union, UCR) directed introduction of the first course on counter-revolutionary warfare in the Higher Military College. By 1963, cadets at the Navy Mechanics School (ESMA) started receiving counter-insurgency classes. In one of their courses, they were shown the movie The Battle of Algiers. Antonio Caggiano, archbishop of Buenos Aires from 1959 to 1975, was associated with this as military chaplain. He introduced the movie approvingly and added a religiously oriented commentary to it.[46] ESMA was later known as a center for the Argentine Dirty War and torture and abuse of insurgents and innocent civilians.[citation needed]

Anibal Acosta, one of the ESMA cadets interviewed 35 years later by French journalist Marie-Monique Robin, described the session:

They showed us that film to prepare us for a kind of war very different from the regular war we had entered the Navy School for. They were preparing us for police missions against the civilian population, who became our new enemy.[46]

2003 Pentagon screening

During 2003, the press reported that United States Department of Defense (the Pentagon) offered a screening of the movie on August 27. The Directorate for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict regarded it as useful for commanders and troops facing similar issues in occupied Iraq.[47]

A flyer for the screening said:

How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas. Children shoot soldiers at point-blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar? The French have a plan. It succeeds tactically, but fails strategically. To understand why, come to a rare showing of this film.[48]

According to the Defense Department official in charge of the screening, "Showing the film offers historical insight into the conduct of French operations in Algeria, and was intended to prompt informative discussion of the challenges faced by the French."[48]

2003–2004 theatrical re-release

At the time of the 2003 Pentagon screening, legal and "pirate" VHS and DVD versions of the movie were available in the United States and elsewhere, but the image quality was degraded. A restored print had been made in Italy in 1999. Rialto Pictures acquired the distribution rights to re-release the film again in the United Kingdom in December 2003 as well as in the United States and in France on separate dates in 2004. The film was shown in the Espace Accattone, rue Cujas in Paris, from November 15, 2006, to March 6, 2007.[49]

Home media

The home media release history of Battle of Algiers is summarized in the following table.

| Title | Released | Publisher | Aspect Ratio | Cut | Runtime | Commentaries | Resolution | Master | Medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #249[50] | October 19, 2021[51] | The Criterion Collection[50] | 1.85:1[52] | 2018 restoration | 2h 02m | none | 2160p | 4K | Blu-ray |

| Dual Edition[53] | May 2, 2018[54] | Cult Films | 1080i/2160p | ||||||

| CULT501 | July 9, 2012[55] | 1080i | |||||||

| #249 | August 9, 2011[56] | The Criterion Collection | 2K | ||||||

| AGTD011[57] | August 30, 2009[58] | Cult Films | 480i | DVD | |||||

| #249[50] | October 12, 2004[50] | The Criterion Collection | 2h 01m | ||||||

| #9322225034198 | 2004 | Madman Entertainment | 1.33:1 | 1h 57m | 576 lines | PAL | |||

| TVT 1085 | February 19, 2001[59] | Palisades Tartan Video[60] | VHS | ||||||

| EE1043[61] | 1993[62] | Encore Entertainment | 1.66:1[63] | 2h 0m[64] | 425 lines | LaserDisc | |||

| RNVD 2108[65] | 1993 | Rhino Home Video[66] | 1.33:1 | 240 lines | NTSC | VHS | |||

| January 9, 1990[67] | Foothill Home Video | 2h 01m | |||||||

| AVC #0208 | 1988 | Axon Video | 2h 5m | ||||||

| ID6786X | 1985 | 2h 02m | 425 lines | LaserDisc[68] | |||||

| CVL1002[69] | October, 1983[70] | Capstan Video | 240 lines | VHS |

Special Editions

2004 Criterion DVD edition

On October 12, 2004, The Criterion Collection released the movie, transferred from a restored print, in a three-disc DVD set. The extras include former US counter-terrorism advisors Richard A. Clarke and Michael A. Sheehan discussing The Battle of Algiers' depiction of terrorism and guerrilla warfare. Directors Spike Lee, Mira Nair, Julian Schnabel, Steven Soderbergh, and Oliver Stone discussed its influence on film. Another documentary in the set includes interviews with FLN commanders Saadi Yacef and Zohra Drif.[71]

See also

- Jamila, the Algerian, a commercial film on the same topic released in 1958.

- Lost Command, a commercial film on the same topic released the same year.

- Chronicle of the Years of Fire, a 1975 Algerian drama historical film directed by Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina. It depicts the Algerian War of Independence as seen through the eyes of a peasant.

- Lion of the Desert, a similar movie about Omar al-Mukhtar's Libyan resistance against Italian occupation.

- List of submissions to the 39th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Italian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

Further reading

- Aussaresses, General Paul. The Battle of the Casbah: Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in Algeria, 1955–1957 (New York, Enigma Books, 2010). ISBN 978-1-929631-30-8.

- O’Leary, Alan. The Battle of Algiers (Milan, Mimesis International, 2019). ISBN 978-88-6977-079-1

References

- ^ a b c "Gillo Pontecorvo: The Battle of Algiers". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers (1967) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Michael J. (1 August 2008). "Slow Looking: The Ethics and Politics of Aesthetics: Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005); Mark Reinhardt, Holly Edwards, and Erina Duganne, Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007); Gillo Pontecorvo, director, The Battle of Algiers (Criterion: Special Three-Disc Edition, 2004)". Millennium: Journal of International Studies. 37: 181–197. doi:10.1177/0305829808093770.

- ^ a b c "Gillo Pontecorvo: The Battle of Algiers". The Guardian.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare Corriere della Sera". www.corriere.it. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ Benjamin Stora, Les Mots de la Guerre d'Algérie, Presses Universitaires du Mirail, 2005, p. 20.

- ^ "The Source". The Battle of Algiers booklet accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD release, p. 14.

- ^ Arun Kapil, "Selected Biographies of Participants in the French-Algerian War", in The Battle of Algiers booklet accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD release, p. 50.

- ^ "Cinquantenaire de l'insurrection algérienne La Bataille d'Alger, une leçon de l'histoire". Rfi.fr. 2004-10-29. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Pier Nico Solinas, "An Interview with Franco Solinas", in The Battle of Algiers booklet accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD release, p. 32.

- ^ J. David Slocum, Terrorism, Media, Liberation. Rutgers University Press, 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Barr Burlin, Lyrical Contact Zones: Cinematic Representation and the Transformation of the Exotic. Cornell University Press, 1999, p 158.

- ^ Peter Matthews, "The Battle of Algiers: Bombs and Boomerangs", p. 8.

- ^ PierNico Solinas, "An Interview with Franco Solinas", in The Battle of Algiers booklet accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD,

- ^ Mellen, Joan (1973). Film Guide to The Battle Algiers, p. 13. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-29316-9.

- ^ "The 39th Academy Awards (1967) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Adam (16 October 2006). "Film Director Gillo Pontecorvo; 'Battle of Algiers' Broke Ground". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bignardi, Irene (2000). "The Making of The Battle of Algiers". Cinéaste. 25 (2): 14–22. JSTOR 41689226.

- ^ a b c d Caillé, Patricia (16 October 2007). "The Illegitimate Legitimacy of The Battle of Algiers in French Film Culture". Interventions. 9 (3). Taylor & Francis: 371–388. doi:10.1080/13698010701618604. ISSN 1469-929X. S2CID 162359222.

- ^ Cowie, Peter, Revolution! The Explosion of World Cinema in the 60s, Faber and Faber, 2004, pp. 172–73

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (10 October 2004). "The cinematic fortunes of war". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (30 May 1968). "The Battle of Algiers movie review (1968)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 May 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "Critics' top 100". bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. 2015-10-02. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema: 6. The Battle of Algiers", Empire.

- ^ "As chosen by you...the greatest foreign films of all time". The Guardian. 11 May 2007.

- ^ a b Wrigley, Nick (February 8, 2018). "Stanley Kubrick, cinephile". BFI. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ LaCinetek. "Costa-Gavras à propos de "La Bataille d'Alger" de Gillo Pontecorvo". YouTube. LaCinetek. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Palmer, R. Barton; Sanders, Steven M., eds. (January 28, 2011). The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3989-0. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

Soderbergh called Traffic his '$47 million Dogme film' and used hand-held camera, available light, and (ostensibly) improvisational performance in an attempt to present a realistic story about illegal drugs. He prepared by analyzing two political films made in a realist style: Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966) and Z (Constantin Costa-Gavras, 1969), both of which he described as having 'that great feeling of things that are caught, instead of staged, which is what we were after.'

- ^ Swapnil Dhruv Bose (14 January 2021). "Steven Soderbergh's 10 best films ranked in order of greatness". Far Out. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

The filmmaker said, 'For this film, I spent a lot of time analysing Battle of Algiers and Z — both of which have that great feeling of things that are caught, instead of staged, which is what we were after. I just wanted that sensation of chasing the story, this sense that it may outrun us if we don't move quickly enough.'

- ^ Mary Kaye Schilling (August 8, 2014). "Steven Soderbergh on Quitting Hollywood, Getting the Best Out of J.Lo, and His Love of Girls". Vulture. Vox Media, LLC. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Paul Cronin (August 5, 2014). Werner Herzog - A Guide for the Perplexed. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-25978-6.

I also recommend Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers, which I admire because of the acting...

- ^ September 16, 20102:16 AM ET (September 16, 2010). "From Werner Herzog, 3 DVDs Worth A Close Look". NPR. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Calum Russell (17 June 2021). "Ken Loach's top 10 favourite films of all time". Far Out. Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Jennifer Vineyard (October 10, 2012). "Ben Affleck on Why He Got to Look Hot in Argo". Vulture. Vox Media, LLC. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

Affleck: "I haven't done a movie that I haven't ripped off from another one! [Laughs.] This movie, we ripped off All the President's Men, for the CIA stuff, a John Cassavetes movie called The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, which we really used as a reference for the California stuff, and then there was kind of a Battle of Algiers, Z/Missing/Costa-Gavras soup of movies, that we used for the rest of it."

- ^ Zack Sharf (May 25, 2017). "Christopher Nolan Reveals How 11 Classic Films Inspired 'Dunkirk'". IndieWire. Penske Business Media, LLC. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

Nolan cited Gillo Pontecorvo's war film as 'a timeless and affecting verité narrative, which forces empathy with its characters in the least theatrical manner imaginable. We care about the people in the film simply because we feel immersed in their reality and the odds they face.'

- ^ Jonathan Lewis (December 20, 2012). "Good guys and bad guys: The Battle of Algiers and The Dark Knight Rises". openDemocracy. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

It was thus with a degree of surprise and interest that I found the latest director to cite The Battle of Algiers as an influence to be Christopher Nolan, the man behind the latest films in the Batman franchise. ... Interviews with Nolan and his team on the making of The Dark Knight Rises indicate that Nolan chose The Battle of Algiers as one of the films for the crew to watch and from which to gain inspiration before they started filming, with Nolan stating that 'no film has ever captured the chaos and fear of an uprising as vividly as [The Battle of Algiers]'.

- ^ "Edward Said Documentary on 'The Battle of Algiers'". Vimeo. 25 December 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Tariq Ali". BFI. British Film Institute. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Epp, Julian; Hoberman, J. (22 June 2023). "The 100 Most Significant Political Films of All Time". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Peter Matthews, "The Battle of Algiers: Bombs and Boomerangs", in The Battle of Algiers booklet accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD release, p. 9.

- ^ Klaus Stern & Jörg Herrmann, "Andreas Baaders, Das Leben eines Staatsfeindes", p. 104.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (13 April 1969). "Pontecorvo: 'We Trust the Face of Brando'". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Breaking the silence: the Catholic Church and the "dirty war" " Archived 2006-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, Horacio Verbitsky, 28 July 2005, extract from El Silencio transl. in English by openDemocracy.

- ^ "Re-release of The Battle of Algiers, Diplomatic License, CNN, January 1, 2004.

- ^ a b Michael T. Kaufman's "Film Studies" Archived 2007-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 7 September 2003.

- ^ See La Bataille d'Alger: Horaires à Paris. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d "The Battle of Algiers". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ "Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut - 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray (Best Buy Exclusive SteelBook) Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved 2024-01-09.

- ^ The Battle of Algiers DVD (DigiPack), retrieved 2024-01-19

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers (Dual Format Edition)". shop.bfi.org.uk. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers". hive.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "The Score, Jul, 2012". PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2012. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "The Criterion Collection". August 9, 2011.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers". hive.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers". hive.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "February releases". The Guardian. 2001-01-19. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "February releases". The Guardian. 2001-01-19. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Battle Of Algiers, The [EE 1043]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Battle Of Algiers, The [EE 1043]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Battle Of Algiers, The [EE 1043]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Battle Of Algiers, The [EE 1043]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "https://rochester.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?context=L&vid=01ROCH_INST:UR01&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&tab=Everything&docid=alma9925215013405216#:~:text=Video%20recording%20publisher%20number%20:%20RNVD%202108". rochester.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "https://rochester.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?context=L&vid=01ROCH_INST:UR01&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&tab=Everything&docid=alma9925215013405216#:~:text=Santa%20Monica,%20CA%20:-,Rhino%20Home%20Video,-;%20New%20York,%20N". rochester.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Filmfax (1990). Filmfax 19 (1990).

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Battle of Algiers, The [ID6786AX]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Battle of Algiers (1965) on Capstan". Pre-Certification Video. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Battle of Algiers (1965) on Capstan". Pre-Certification Video. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "The Battle of Algiers Details :: Criterion Forum". criterionforum.org. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

External links

- The Battle of Algiers at IMDb

- The Battle of Algiers at the TCM Movie Database

- The Battle of Algiers at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Battle of Algiers at AllMovie

- The Battle of Algiers at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Battle of Algiers at Metacritic

- Official website at Rialto Pictures

- The Battle of Algiers: Bombs and Boomerangs an essay by Peter Matthews at the Criterion Collection