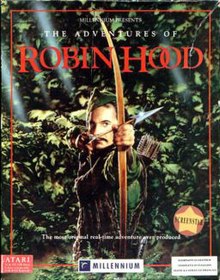

The Adventures of Robin Hood (video game)

| The Adventures of Robin Hood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Millennium Interactive |

| Publisher(s) | Millennium Interactive |

| Designer(s) | Stephen Grand Ian Saunter |

| Programmer(s) | Steve Grand[1] |

| Artist(s) | Robin Chapman[1] |

| Composer(s) | Richard Joseph |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS, Atari ST, Amiga |

| Release | September 1991[1] |

| Genre(s) | RPG, adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Adventures of Robin Hood is a video game released in the autumn of 1991 by Millennium Interactive.

Plot summary

The protagonist, Robin of Loxley, is robbed of his castle by the Sheriff of Nottingham and has to get it back with the help of Maid Marian, Little John, Will Scarlet and Friar Tuck.

Gameplay

The gameplay can be described as an action RPG. The player controls Robin as he robs from the rich to give to the poor, adventures through Sherwood Forest, defeats the sheriff's henchmen, gathers special objects and saves peasants. Heroic acts increase Robin's popularity among NPCs; as well as defeating the Sheriff, Robin must ensure that certain stats do not become negative to ensure a successful completion of the game. Archery plays an important role in gameplay.

Robin is able to collect 7 magic or special items (represented by the icons: habit, ring, feather, toadstool, bolt, horn, crystal ball) by interacting with other characters or the environment.

The isometric interface developed for The Adventures of Robin Hood by Millennium Interactive is similar to the interface used in Populous. Robin Hood's interface was later used for Rome: Pathway to Power.

Development

The Adventures of Robin Hood began development in July 1990, and was released in September 1991 for Amiga, Atari ST, and DOS.[1] British gaming magazine The One interviewed Steve Grand, Robin Hood's programmer, for information regarding its development in a pre-release interview.[1] According to Grand, Robin Hood was initially conceived as a game about cowboys, but he expresses that "we got part way through it though, and feelings changed about where it was going and what it was going to be. Then someone idly suggested Robin Hood and I thought 'Yeah I'll do it".[1] Grand notes adaptations of Robin Hood in pop culture, stating that "everybody knows the Errol Flynn side of Robin Hood, but not a lot of people realize that a major part of the legend is mythological", and expresses that both 'Hollywood' depictions of Robin Hood and the mythological interpretation are incorporated into the game.[1] The icons for spells in Robin Hood are based upon Anglo-Saxon paganism and Norse mythology.[1] A major design aspect of Robin Hood is making the game 'flexible' towards differing playstyles, and Grand states in regards to this that he "didn't want it to be the kind of adventure where you've got one single fixed sequence and if you cock up one bit of it you've blown the lot. There are any number ways of winning - and hopefully there'll be any number of ways of losing too".[1] Robin Hood was created using a custom adventure-creation engine created by Grand, titled Gulliver, and formerly titled Microcosm.[1]

Grand cites the Gulliver engine's NPC management as an advantage that it has over other engines, stating that "all the people [in the game] are behaving consistently all the time, they're all there, they're all doing things off stage. It's not like rooms [which] disappear when you're not in them". Grand furthermore notes how NPCs 'notice' other NPCs and interact with one another, expressing that "what's clever about it is that there are 40 people in there who can see or not see, hear or not hear eachother [sic] - that's proper interaction and the system doesn't cheat".[1] Every sprite in Robin Hood is marked with AI routines, and Grand states that "the whole system is object oriented, they've all got their own rule bases".[1] At that stage of development, Robin Hood was stated to be coded with 600 rules, with this number projected to 'about 1,500' when the game was finished.[1] Each of the 'around forty' characters and objects in Robin Hood have AI routines for different scenarios, and every sprite has 32 attributes.[1] In the case of characters, these attributes are stated by Grand to "make up their soul", and determine factors such as "how hungry they are, how optimistic they're feeling, who they like, [and] what sort of people they are".[1] The values for these attributes change frequently due to every decision being determined by one or more attributes, and these decisions are impacted by what characters are nearby.[1] Grand expresses that his long-term goal for Robin Hood was for it feel like an open world game, stating that "ultimately what I want to do is write a computer game with no plot in it whatsoever. I just want to build the world and put the people in it so that you can do whatever you want to do".[1]

Robin Hood has a total of 64 different locations, and Grand expresses that while "Isometric [graphics are] a bit dated", "it's a good way of getting 3D on the cheap. At the moment the system can't do first person 3D fast enough - even now about 90 percent of the processing time is just taken up by plotting screens".[1] Memory restrictions were noted as a difficulty in Robin Hood's development, and an example is given of a swan that 'doubles as' a coffin; if a character dies and the coffin is loaded into memory, the swan disappears.[1] Robin Hood's graphics were first drafted by Steve Grand, and then finalized by graphic artist Robin Chapman.[1]

Reception

Reviewer Gary Whitta gave the PC version 820 out of a possible 1000 points, praising the graphics, controls and sense of involvement.[2]

The One gave the Amiga version of Robin Hood an overall score of 80%, calling it "atmospheric" and stating that the changing of seasons in-game gives "a sense of urgency", further noting how NPCs "lead independent lives" outside of the player's involvement. The One praises the game's flavor text and sense of humour, expressing that humour "is very difficult to achieve in a computer game". The One compares the game's graphics to Populous, but states that the gameplay is dissimilar, as "the map is much smaller and the action is directed towards achieving one specific goal". The One also praises the amount of content and Robin Hood's replayability, noting the amount of dialogue with NPCs and the ability to solve puzzles differently. The One criticizes the amount of time it takes to get to different locations, saying that "it can be annoying waiting for Robin to cross from one side of the map to the other, particularly because he can only walk in four directions".[3]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Hamza, Kati (April 1991). "Making Merry". The One. No. 31. emap Images. pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b Whitta, Gary (October 1991). Robin Hood (review of PC version). ACE, p. 64–65.

- ^ a b Houghton, Gordon (September 1991). "Review". The One. No. 36. emap Images. pp. 66–67.

- Upchurch, David (July 1991). The new Millennium (sic). ACE, p. 60.

- Review of Adventures of Robin Hood by Methat, server Revival of DOS Games, 22.12.2008