Tape ball

A tape ball is a tennis ball wrapped in electrical tape that is often used in informal games of cricket such as street cricket, also called tape ball cricket.a First pioneered in Karachi, Pakistan,[1][2] the tape ball acts as an improvised cricket ball with the tape stretched tightly over the fuzzy felt-like covering of a tennis ball to ensure a smooth surface that produces greater pace after bouncing.[3] Although most street games feature entirely covered varieties, tape balls may also be prepared such that only one side is taped to replicate reverse swing or they may have multiple layers of tape running down the middle to mimic the leather seam found on standard cricket balls.[4] Applying tape makes the ball heavier than a tennis ball, but not as hard or heavy as a cricket ball. As such, this modification seeks to reduce the risks to players, passers-by and property.[5]

History

The practice of using electrical tape to repurpose the ball originated in Karachi street cricket during the 1960s,[6] quickly spreading from neighbourhoods in Nazimabad and the Federal B. Area.[7] This approach of modifying the ball built on previous unsuccessful attempts implemented by local bowlers, such as constantly wetting shaved tennis balls to make them heavier and more conducive to skidding through quickly after bouncing. Partly introduced to include individuals who were unable to access pitches and protective equipment, the tape ball innovation also countered the prodigious amounts of spin that skilled bowlers could extract when playing with tennis balls.[8] One such exponent was former first-class cricketer Nadeem Moosa, who would squeeze the ball between his middle-finger and thumb before flicking it on release. The glossy surface of a tape ball would make this unorthodox, carrom-like grip difficult and bowlers focusing on speed, rather than turn, would start to find success.[9][10] For up-and-coming batsmen such as Javed Miandad, who was involved in the early tape ball scene in Gazdarabad, this new way of playing instilled determination and resolve against the quickest bowlers.[11]

In the 1980s, tape ball cricket circuits started to emerge across Pakistan where fiercely competitive games would be played in front of several hundred spectators and formal rules were drawn up. For example, the 'K2 Brother Cricket Tournament', referred to as a series of tape tennis matches, allowed for 8 players and 8 overs per side and also stipulated the use of the Japanese tape manufacturer, Netto, which was deemed to have the highest quality of available brands. Any batsman hitting the ball into a house would also immediately be declared out.[12] During this decade, the tape ball trend spread to affluent areas, such as Defence and Clifton and was now enjoyed by lower and upper classes alike.[13] In addition, the 'professional' tape ball player emerged. These were especially talented cricketers who would be hired to play in games for different teams in exchange for a small payment. Wasim Akram became a professional tape ball player in Lahore in 1983, a year before he would begin his test match career.[14]

By the early 1990s, tape ball cricket continued to enjoy popularity in practically every city and most of Pakistan's national side comprised the likes of Miandad, Akram and other cricketers who had grown up playing it. For children and young adults of the time, Pakistan's 1992 World Cup victory saw nationwide interest in the sport grow even more and tape ball was thriving amongst a new generation of fans who had been galvanised by their homeland's achievement.[15] Non-pecuniary rewards associated with amateur tape ball tournament performances now included the izzat (honour) amongst one's community and feelings of personal pride. The most successful players on the circuit would be garlanded with flowers, greeted with celebratory gunfire and paraded to grounds on horseback.[16]

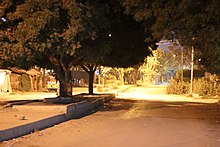

Towards the end of the 20th century, tape ball games were widespread even in slums and on mountains and battlefields, as the previous novelty had long become an entrenched part of Pakistan's sporting culture.[17] In 1999, Tariq Ali wrote that "the gulli-danda days are over" [referring to a previously ubiquitous sport] and Ramzan tape ball cricket tournaments were celebrated annual events.[18] Held during the holy month of ramadan, the informal nature of these tournament games (which could last from 5 to 25 overs) would often be played late into the evenings for short periods of recreation before the commencement of daily fasting and morning prayers.[19][20]

Behaviour of the ball

Any colour of tape can be used and its application means tennis balls face less air resistance and travel quickly. This allows bowlers to bowl at high speeds while also ensuring batsmen can hit shots that continue over longer distances.[21][8] On occasions where quick runs are needed, a lighter bat will be used to hit the ball even further by increasing the speed of bat-swing and scores over 20 runs per over or six sixes are not uncommon.[22][7][23] As they are both lighter and smaller, tape balls have been estimated to travel 20 per cent faster in the air than cricket balls and this encourages increased arm-speed.[24] Factors such as the style of bowling action, how evenly the tape is applied and which brand of tape is used may vary behaviours slightly and the bounce of the tape ball can often be unpredictable.[25][13] It has been suggested that the tendency for the ball to deviate as it hits the ground helps develop batting reflexes and encourages unorthodox styles. The tape ball also incentivises bowlers to work harder on their wrist technique due to the greater probability of swing.[18]

Given its history of being introduced to negate finger spinners, the smooth surface of a tape ball (with no seam) naturally offers less turn than a tennis ball or cricket ball. Due to this, spinners are necessitated to expand their range of skills, such as having to bowl faster or to mix googlies and offbreaks throughout their overs.[20] Shahid Afridi is one such bowler who developed a varied repertoire based on playing with a tape ball, as did Rashid Khan who learned the importance of experimentation when devising new variations in his youth.[26]

With the abrasive grounds this type of cricket is commonly played on, the tape is not particularly durable and quickly develops scratches and tears. Furthermore, loose pieces of ripped tape can alter how the ball behaves, such as making it swing appreciably late, making deviation from spinners unpredictable or resulting in even more uneven bounce. In certain cases (depending on the local rules or availability of more rolls of tape), the tape is left to wear naturally. When torn, however, the ball is usually immediately re-taped or replaced with a pre-taped ball as often as required before the specified number of overs are completed.[27] As late swing is relatively easy to achieve, tape balls have occasionally been utilised by professional test cricketers who have incorporated them as part of training drills, such as Yasir Hameed and Mohammad Rizwan.[28][29]

Taking inspiration from these properties, the concept has been adapted in wiffle ball where the perforated, plastic ball is covered in electrical or, rarely, duct tape to make it heavier and thereby act more like a baseball when pitched.[30] As with cricket, this has sometimes been used to ease children from a softer to harder ball.[31]

Impact and legacy

Influence

Tape ball cricket is considered an integral part of Pakistani cricket and sports culture, with virtually every cricket-playing youth being exposed to it in one form or another. Its introduction shifted the status of cricket in the country from an elite to a mainstream sport that could even be enjoyed by those living in abject poverty.[32] Aspirational cricketers born into difficult circumstances have since been able to rise from hardship and win selection for the national teams. For instance, Mohammad Yousuf, whose family were not able to afford tennis balls, honed his talent as a child by wrapping a ping-pong ball in tape and using a thaapi as a makeshift bat.[33][34] In 2005, it was estimated that, of all those who play some kind of organised cricket in Pakistan, 80 per cent play with a tape ball, and 20 per cent with a standard cricket ball.[25] The inexpensive alternative has also been praised for its role in mitigating dangers associated with standard cricket balls, particularly head injuries in children that have previously been fatal.[35] Because of how widely it has always been played, this form of cricket continued to provide a steady stream of talented athletes that helped keep Pakistan's domestic cricket afloat when the national side were forced to play away from home for almost a decade, following the 2009 Lahore attack.[36]

The popularity of tape ball is also credited with Pakistan's famous production of fast bowlers and, according to Shaheen Afridi,[37] may provide reasoning for Pakistani bowlers' effectiveness in bowling yorkers, particularly in the death overs of white ball cricket. As there is usually no leg before wicket (lbw) rule in tape ball games, bowlers are rewarded for bowling full and straight to target the stumps (aiming to bowl the opponent).[38] Umar Gul, one of Pakistan's most successful T20 bowlers and yorker exponents, did not transition from tape to cricket ball until he was 16.[20] Similarly, Haris Rauf worked as a professional tape ball player, freelancing for various clubs that required his services of 'hitting the blockhole ball after ball'.[39] Other notable pace bowlers picked based on their tape ball talent include Shoaib Akhtar,[25] who became the fastest bowler of all time and Mohammad Amir,[23] who was scouted during a tape ball tournament when he was 13 years old.

Despite not being officially recognised by cricket boards, contemporary tape ball tournaments have continued to become increasingly elaborate based on demand from prospective players and audiences. Local tournaments feature extravagant opening ceremonies (consisting of music, dance, fireworks etc.) and receive widespread media and commercial support in Pakistan. With Ramzan cricket alone said to be worth Rs (PKR) 100 million, there are numerous opportunities to provide substantial monetary value to participants.[40] In 2015, a 15 night tournament in Karachi offered prize money of Rs 300,000 and additional rewards, such as The Man of the Tournament receiving a motorbike.[9] The best of these professional players often receive additional gifts from adoring fans, employ unique pseudonyms that are emblazoned on their bats and are celebrated in hundreds of YouTube fan videos.[41][42] Most organised games involve branded team kits, are streamed online and have live commentary provided through pitch-side loud speakers.[16]

In 2020, Wisden named tape ball in their list of the ten greatest cricket inventions.[43] Such has been the impact, that in recent years specialised grounds have been set up for tape ball[44] and ball manufacturers have introduced specialised products designed to act like cricket balls, which have proven to be popular throughout Pakistan.[45][46] Similarly, in an attempt to remedy the inconvenience of constantly replacing tape, the windball has been used for informal games in England and the West Indies.[47] For batsmen, CA Sports produce 500,000 specialised tape ball bats per year which vary in length, width and weight as compared to regular cricket bats, and are more curved.[48]

Effects on player development

Regarding skill development, tape ball tournaments have featured the paddle scoop since the 1970s and have been attributed as a key launchpad for the invention of reverse swing and the doosra, both also first conceived in Pakistan.[9][49][50] However, the potential benefits and drawbacks offered by this variety of cricket have sometimes been debated by former players and commentators. While some have theorised the lighter ball builds muscle[14] and improves control[24] for fast bowlers, others have suggested that too much tape ball can harm the development of good spin bowlers. Former leg spinner Danish Kaneria played in several Karachi tape ball tournaments as a boy in the 1990s but was later stopped from participating as his coach felt the softer, smaller ball would make it difficult for his pupil to master the hard cricket ball[13] In another case, Shadab Khan started as a fast bowler in tape ball cricket and only considered leg spin a viable option when he was introduced to the standard cricket ball.[51]

Tape ball is pure entertainment, however it can have an adverse affect on the technique of the batsmen as the challenges posed by a cricket ball are totally different to a taped one, professional cricketers can have the odd indulgence especially during Ramazan, however they should not play this version regularly

—Mohsin Khan, former test cricketer[13]

From a batting perspective, former test captains Misbah-ul-Haq and Younis Khan have stated that tape ball experiences helped them play with a straight bat and improved their hitting ability during their youth.[52][7] Conversely, ex-cricketers including former national coach and selector Mohsin Khan have claimed that this version of cricket can have a detrimental effect on batting technique.[13] Consistently playing tape ball games has been cited as a reason for Pakistan's poor fielding in the past, specifically because playing on rough surfaces has developed an aversion to diving.[53]

Concerns have been voiced about how the increased ease of starting cricket and the pull of local tournament fame wrongly persuade impressionable children to drop out of school and pursue the sport.[54] It has also been pointed out that the draw of these lucrative opportunities is exacerbated by the pervasiveness of T20 leagues as they offer further reward, often through the same skills that are refined with tape ball experience.[55] This was particularly well illustrated in Pakistan when a talent-hunt programme launched by Lahore Qalanders found that approximately half of their 350,000 applicants were tape ball players.[56]

Expansion beyond Pakistan

Test nations

Since its inception, tape ball cricket has drawn interest from outsiders due to how the indigenous idea spread so quickly and achieved institutionalisation within Pakistan, as well as its longevity over decades and the impact it has had on the international game.[3][57] In neighbouring Afghanistan, tape ball cricket has perhaps had greatest influence among the other test-playing nations, helping produce players such as Taj Malik, Rashid Khan and Hazratullah Zazai.[58][59] In refugee camps housing Afghans following the Soviet–Afghan War, interest in cricket swelled and tape ball found popularity within the displaced community living in Peshawar and other areas close to the Afghanistan border.[60]

Although the timing of events indicates that the tape ball did not feature much in East Pakistan, the game has been enjoyed in Bangladesh for several years. Tournaments have been organised in multiple localities and have helped the nation consistently identify fast bowling prospects.[61] International cricketers to emerge from the tape ball circuit include Shakib Al Hasan, Mustafizur Rahman, Rubel Hossain and Elias Sunny.[62]

Aside from infrequent street games and occasional tournament appearances, there is comparatively less tape ball played in India and Sri Lanka, where tennis ball cricket tends to be more popular.[57][63] However, the idea has been harnessed in Sri Lankan school cricket competitions to facilitate children's transition towards a harder ball.[64] Previously, former cricketers from the Sri Lankan team including Russel Arnold and Upul Chandana have participated in a yearly tape ball tournament in the Maldives to help promote cricket in the nation.[65]

Away from Asia, the game has been advocated in other test nations where it can be enjoyed by locals and the Pakistani diaspora who have frequently helped establish it. Specifically, the tape ball concept has gained popularity with communities in England, Australia and the West Indies:

In 2005, hoping to capitalise on the enthusiasm created by England's win in the 2005 Ashes series, the London Community Cricket Association began organizing tape ball cricket teams for children on estates in inner-city London, where a lack of playing fields has led to a decline in popularity for traditional cricket.[66] The matches use a variant of the Twenty20 Cricket rules designed to make matches last a half-hour or less. This initiative was followed up with a National Cricket Day organised by Chance to Shine that held tape ball cricket competitions for thousands of children across London housing estates.[67] Partnering with the Yorkshire Cricket Board, the charity also launched the Chance to Shine Street Programme which has been praised for encouraging girls to take up the sport.[68] Also enjoyed informally, England captains Eoin Morgan and Moeen Ali both grew up playing tape ball.[69][70]

Since 2010, Australia has hosted an annual Tape Ball Cricket Cup which is based in Sydney.[71] Similarly, a group of Sri Lanka born Australians have promoted the idea across Victoria, however, with the popularity of backyard and indoor cricket in the country, tape ball is still mostly popular amongst the South Asian communities.[72]

In the West Indies, tape ball has been popular for many years, particularly in Barbados where games are played on the streets, as well as in more formal settings.[73] Evening games of tape ball have been organised to raise funds for various charities, with celebrities participating during nights that also include music from live DJs and other entertainment.[74] Bajan fast bowlers Tino Best and Jofra Archer started playing when at school and honed their ability to bowl at extreme pace during these competitions.[75][76] Furthermore, in Antigua and Guyana, interest in tape ball has steadily risen,[77] with different tournaments taking place amongst clubs from the islands.[78][79]

Associate nations

Tape ball cricket has also had a degree of influence on nations that do not typically partake in much competitive cricket, such as in central Asia where games played in Tajikistan (through the Tajikistan Cricket Federation) and Kazakhstan (at the Almaty Cricket Club) have been credited with sparking interest in the sport and positively contributing to the community.[80][81] Additionally, tape ball leagues have been organised in parts of continental Europe, including Greece, Malta and The Netherlands.[82][83][84]

Although cricket is not as popular as other sports in the Americas, tape ball has been played in the United States, Canada and in parts of South America. At Princeton University, this type of cricket has been used to introduce the sport and eventually have local athletes switch to standard cricket.[85] In Houston, several clubs now offer children coaching in leather ball as well as tape ball.[86] Ali Khan, who grew up in Pakistan and played in various tape ball tournaments, represents the USA national team.[87] In several municipalities of the Greater Toronto Area, such as Mississauga, cricket tournaments are a common sight during ramzan nights.[88] A domestic tape ball league was started in Uruguay in 2012, with over 100 active players taking part.[89]

Due to historic international ties with Pakistan, it is perhaps unsurprising that the tape ball concept has flourished in the Middle East. In Dubai, many Pakistani and Indian expatriates play together in the mornings to evade the afternoon heat,[90] while in Sharjah workers play multiple tape ball games every Friday.[91] When working as bowling coach for the UAE team, former fast bowler Aaqib Javed stressed the importance of tape ball to improve the pace and quality of the nation's fast bowling resources.[92] Since then, the concept has gathered momentum and the UAE is home to the annual Chinar Super League (CSL) which has occasionally featured cricketers associated with the Pakistan Super League.[93]

See also

- Cricket ball

- Cricket clothing and equipment

- Cricket in Pakistan

- Pakistani cricket team

- Tennis ball cricket

Notes

[a] The term tape ball can refer to the covered tennis ball itself or act as a synecdoche for the type of cricket games played with it. Hence, 'tape ball' and 'tape ball cricket' are frequently used interchangeably, as is the case in this entry.

References

- ^ Naqvi, Ahmer. "The Jugaaroo". thecricketmonthly. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Waterhouse, Ann (2016). An Entertaining Introduction to the Game for Mums & Dads. Meyer & Meyer Sport, Limited. ISBN 9781782550792.

- ^ a b Samiuddin, Osman (11 July 2006). "Pakistan's quicks get into the swing with tennis balls and electrical tape". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Pipe, Jim (2012). Cricket: A Very Peculiar History. Salariya Book Company Limited. ISBN 9781908759740.

- ^ Rundell, Michael (2009). Wisden Dictionary of Cricket. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408101612.

- ^ F. Paracha, Nadeem (24 July 2014). "Street cricket in Pakistan: A personal history". Dawn. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Heller, Richard. "Tape-ball cricket: a league of its own". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b Nagi, Iftikhar (14 July 2015). "Tape-balls and their love affair with Pakistan's streets". Dawn. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Hussain, Abid. "Tape-ball tales". thecricketmonthly. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Samiuddin, Osman (2014). The Unquiet Ones: A History of Pakistan Cricket. HarperCollins India. ISBN 978-9350298015.

- ^ Haigh, Gideon. "Agent provocateur". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Mughal, Owais (3 November 2009). "Rules of a Street Cricket Tournament". pakistaniat. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Hameed, Emmad (10 August 2011). "Of Ramazan and tape ball cricket". Dawn. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Staff Report (26 March 2021). "Pakistan cricket stars recall 1992 World Cup glory". dailytimes. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b Nobil Ahmed, Ali (19 May 2019). "Tape ball: the user-friendly alternative to cricket invented by Pakistan's poor". thenationalnews. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Astill, James (2013). The Great Tamasha. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408192207.

- ^ a b Ali, Tariq (15 July 1999). "Anyone for gulli-danda?". London Review of Books. 21 (14). Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Khattak, Muhammad Yasir Nawaz. "Street cricket – Finest childhood memory of a Pakistani". thepakistani. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Samiuddin, Osman. "Drastic fantastic comes easy to Pakistan". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Qamar, Kashif (27 June 2002). "Pakistan's sticky business". BBC. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Cheema, Ikram Bari (7 April 2017). "White on Green: A reflective recollection of Pakistan's cricket journey". tribune. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b Samiuddin, Osman. "Who is the real Mohammad Amir?". thecricketmonthly. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b Chakrabarty, Shamik (4 August 2019). "Speed and yorker, the main currencies in tape-ball cricket". The Indian Express. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Dyson, Jonathan (13 November 2005). "Getting it taped on Saturday night". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Wigmore, Tim; Wilde, Freddie (2019). Cricket 2.0 Inside the T20 Revolution. Birlinn. ISBN 9781788851886.

- ^ Gardner, Alan. "It's tape-ball cricket, east London style". thecricketmonthly. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Riaz, Hameed eager to make call-ups count". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Zafar, Waqas. "Rizwan: 'Practiced against the tape ball to prepare myself for reverse swing'". Crickwick. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Paschal, John (2 July 2019). "What Wiffleball Once Taught Us". The Hardball Times. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Ripkin Jr, Cal. "Offseason play, even with lighter ball, keeps kids' interest". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ shafqat, saad. "Transcript: Couch Talk with Saad Shafqat". thecricketcouch. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Samiuddin, Osman. "Thank god it's Yousuf". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Pitches to be revamped, says Tauqir". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Howe, Maddox (2018). Management of Sports and Physical Education. EDTECH. ISBN 9781839473708.

- ^ Atherton, Mike (2011). Glorious Summers and Discontents: Looking Back on the Ups and Downs from a Dramatic Decade. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 9780857203502.

- ^ Wigmore, Tim (11 November 2021). "Shaheen Shah Afridi: Pakistan's tapeball talent on destroying India and marrying his hero's daughter". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Shakoor, Abdul (October 2018). "Here's How Tape Ball Cricket Is Played In Pakistan". parhlo. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Farooq, Umar (12 November 2021). "'A superstar Pakistan deserves' The rise and rise of Haris Rauf". dailytimes. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Lakhani, Faizan. "Ramzan Cricket: A festival worth 100 million rupees". The News. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Pakistan's Tape Ball Cricket - BBC URDU". BBC Urdu. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Bukhari, Mubasher (July 2019). "Street star Shahbaz Kalia is the most famous batsman you've never heard of". Arab News. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Wisden Staff (4 August 2020). "The Ten: Cricket's greatest inventions – From Hawk eye to the Merlyn". Wisden. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Jheel Park to get tape-ball cricket ground". The Express Tribune. 27 December 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "A hard tennis ball designed for play in cricket". Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

- ^ Guardian Sport (19 July 2017), Have you heard of Tape Ball cricket?, archived from the original on 19 December 2021, retrieved 23 July 2017

- ^ Cox, Gary (2018). Cricket Ball. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350014596.

- ^ "A Look at the History of CA Sports". CA Sports. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Hughes, Simon. "How Wahab put England into reverse". The Analyst. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Johnston, Rob (16 April 2020). "Saqlain Mushtaq: Surrey's premier match-winner". Widen. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Lakhani, Faizan. "Skillful Shadab aims to be the all-rounder for Pakistan". Geo. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Cheema, Hassan. "The logician". thecricketmonthly.

- ^ Hussain, Bilal. "Electric tape and tennis balls". thenews. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Khan, Shaharyar; Khan, Ali (2013). Cricket Cauldron: The Turbulent Politics of Sport in Pakistan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857733177.

- ^ Yaqoob, Mohammad (11 December 2019). "Khalid, Aqib and Aslam raise concern over PCB's wrong priorities". Dawn. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Hashmi, Shahid. "Even the PM's a fast bowler: Pakistan cricket's need for speed". Yahoo News. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Rahul (2012). Pundits from Pakistan: On Tour with India 2003-04. Penguin Books India. ISBN 9788184756975.

- ^ Atherton, Mike. "Afghanistan's rise from Peshawar refugee camps to cricketing elite". The Times. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Gollapudi, Nagraj. "Rashid Khan: 'You can get form back, but once you lose respect, it's hard to get that back'". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Haigh, Gideon (2014). Uncertain Corridors: The Changing World of Cricket. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 9781471132797.

- ^ TBS Staff (24 November 2021). "'It all started from tape-tennis cricket': Raja". The Business Standard. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Lynch, Steven (2013). The Wisden Guide to International Cricket 2014: The Definitive Player-by-Player Guide. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408194744.

- ^ Ali, Sarfraz (26 November 2016). "Pakistan, India to play tape ball cricket tournament in Sharjah". Daily Pakistan. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ The Sunday Times. "Under 17 Girls tape-ball cricket starts today". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Maldives Cricket. "History & Profile". maldivescricket. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Pryor, Matthew (6 October 2005). "Tapeball craze helps kids to bend it like Flintoff". The Times. London. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ "Thousands of children to take part in Britain's biggest ever day of cricket in schools". Chance To Shine. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Fuller, John. "How Chance to Shine Street launched a new cricket club in Sheffield". Cricket Yorkshire. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Bull, Andy. "Eoin Morgan: T20 evolution must work in tandem with protection of Test cricket". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Rawlings, Tom. "Birmingham's Spark Green Park transformed for The Hundred in honour of local captain". Edgbaston. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Danielle. "World's most version of street cricket comes to Kingsgrove with Seventh Tape Ball Cricket Cup". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "TAPED-BALL CRICKET GOING GLOBAL". TTS Group. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Cozier, Tony. "A taste of Bajan cricket (10 February 1999)". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Starcom Network Celebrity T20 Tape-Ball Cricket Match – Conquering Lions Vs Legal Eagles". What's On In Barbados. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Best, Tino; Wilson, Jack (2016). Mind The Windows: Tino Best - My Story. John Blake. ISBN 9781786061775.

- ^ Hoult, Nick; James, Steve (2020). Morgan's Men: The Inside Story of England's Rise from Cricket World Cup Humiliation to Glory. Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781760874834.

- ^ "Roberts's journey from silent assassin to genial groundsman". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Warriors Claim Tape Ball Title". Antigua Observer. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Tape ball tourney set for Saturday on Durban Park Tarmac". Kaieteur News Online. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Connelly, Charlie (2014). Elk Stopped Play And Other Tales from Wisden's 'Cricket Round the World'. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408832387.

- ^ Munro, Tony. "Cricket round the world". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Tagaris, Karolina. "Pakistan's street cricketers bring game to life in Greece". Reuters. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Malta Cricket Association. "Spirit of Cricket shines through Tape Ball League in Malta". cricketworld. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "KNCB Tapeball Rules and Regulations indoor seniors competition 2017" (PDF). Cricket Festival. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Princeton University Joins American College Cricket". cricketworld. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "First National Level Youth Cricket Tournament Hosted in Houston". IndoAmerican-News. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Della Penna, Peter. "How USA's Ali Khan got to the IPL (with a little help from Dwayne Bravo)". ESPN cricinfo. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Zaidi, Ashar. "Playing cricket the Canadian way on Ramzan nights". Geo News. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Cricket In Uruguay". emergingcricket. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Radley, Paul. "The Stars of Street Cricket". The National. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Farooqui, Mazhar. "Watch: 25 cricket matches played simultaneously on one ground in Sharjah". Gulf News. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Nayar, K.R. "Tape-ball is Javed's recipe for pacers". Gulf News. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Chinar Super League: UAE's 'largest tape ball community cricket cup' dates announced". Gulf News. Retrieved 24 April 2022.