Stromboli (1950 film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

| Stromboli | |

|---|---|

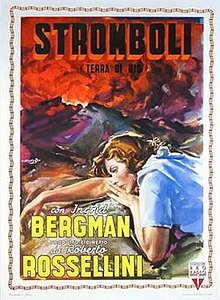

Italian theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roberto Rossellini |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Roberto Rossellini |

| Produced by | Roberto Rossellini |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Otello Martelli |

| Edited by | Jolanda Benvenuti |

| Music by | Renzo Rossellini |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 107/81 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages | Italian, English |

| Budget | US$900,000[1] |

Stromboli, also known as Stromboli, Land of God (Italian: Stromboli, terra di Dio), is a 1950 Italian-American film directed by Roberto Rossellini and starring Ingrid Bergman.[2] The drama is considered a classic example of Italian neorealism.[citation needed]

In 2008, the film was included on the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage’s 100 Italian films to be saved, a list of 100 films that "have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978."[3]

Plot

Bergman plays Karin, a displaced Lithuanian in Italy, who secures release from an internment camp by marrying an Italian ex-POW fisherman (Mario Vitale), whom she meets in the camp. He promises her a great life in his home island of Stromboli, a volcanic island located between the mainland of Italy and Sicily. She soon discovers that Stromboli is very harsh and barren, not at all what she expected, and the people, very traditional and conservative, many fishermen, show hostility and disdain towards this foreign woman who does not follow their ways.

Karin becomes increasingly despondent and eventually decides to escape the volcanic island.

Cast

- Ingrid Bergman as Karin

- Mario Vitale as Antonio

- Renzo Cesana as The Priest

- Mario Sponzo as The Man from the Lighthouse

- Gaetano Famularo as Man with Guitar

- Angelo Molino as Baby, uncredited

Most villagers are played by actual people from the island, as is typical of neorealism.[citation needed]

Background

The film is the result of a famous letter from Ingrid Bergman to Roberto Rossellini, in which she wrote that she admired his work and wanted to make a movie with him. Rossellini and she set up a joint production company for the film, Societ per Azioni Berit (Berit Films, sometimes written as Bero Films), and she also helped Rossellini to secure a production and distribution deal with RKO and its then owner, Howard Hughes, thus securing most of the budget together with international distribution for the film. Originally, she had approached Samuel Goldwyn, but he bowed out after having seen Rossellini's film Germany, Year Zero.[4]

The terms of Rossellini's contract with RKO stated that all footage had to be turned over to RKO, which would edit an American version of the film, based on Rossellini's Italian version. However, the US version was eventually made without the director's input. Rossellini protested, and claimed that RKO's 81-minute version was radically different from his original 105-minute version.[4] Rossellini obtained support from Father Félix Morlión, who had been involved in the screenwriting. He sent a telegram to Joseph Breen, director of MPPDA's Production Code Administration, urging him to compare the original script with the RKO version, as he felt that the religious theme he had written into the screenplay had been lost.[5] The conflict eventually led to Rossellini and RKO taking legal action against each other over the international distribution rights to the film.[4] The exact outcome is unknown, but the unrestored RKO version of the film, as distributed, is 102–105 minutes long. It lists credits that were missing in the first RKO version, but it still has 1950 as the production year, and the same MPAA number as the 81-minute version. This indicates that the differences were resolved rather quickly.

Some confusion surrounds the Italian release date of the film. Modern sources list the release year as either 1949 or 1950,[4] but an Associated Press article dated March 12, 1950, reported that the film had not yet been shown publicly in Italy.[6] Apparently, few Italians had a chance to see the film until it was screened at the 11th Venice International Film Festival on August 26, 1950.[7]

Stromboli is perhaps best remembered for the extramarital affair between Rossellini and Bergman that began during the production of the film, as well as their child born out of wedlock a few weeks before the film's American release.[8] In fact, the affair caused such a scandal in the United States that church groups, women's clubs, and legislators in more than a dozen states around the country called for the film to be banned,[9] and Bergman was denounced as "a powerful influence for evil" on the floor of the US Senate by Colorado Senator Edwin C. Johnson.[10] Furthermore, Bergman's Hollywood career was halted for a number of years, until she won an Academy Award for her performance in Anastasia.

Critical reception

In Italy, Stromboli was awarded the Rome Prize for Cinema as the best film of the year.[7][11]

Initial reception for Stromboli in America, however, was very negative. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times opened his review by writing: "After all the unprecedented interest that the picture 'Stromboli' has aroused — it being, of course, the fateful drama which Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini have made — it comes as a startling anticlimax to discover that this widely heralded film is incredibly feeble, inarticulate, uninspiring and painfully banal." Crowther added that Bergman's character "is never drawn with clear and revealing definition, due partly to the vagueness of the script and partly to the dullness and monotony with which Rossellini has directed her."[12] The staff at Variety agreed, writing, "Director Roberto Rossellini purportedly denied responsibility for the film, claiming the American version was cut by RKO beyond recognition. Cut or not cut, the film reflects no credit on him. Given elementary-school dialog to recite and impossible scenes to act, Ingrid Bergman's never able to make the lines real nor the emotion sufficiently motivated to seem more than an exercise ... The only visible touch of the famed Italian director is in the hard photography, which adds to the realistic, documentary effect of life on the rocky, lava-blanketed island. Rossellini's penchant for realism, however, does not extend to Bergman. She's always fresh, clean and well-groomed."[13] Harrison's Reports wrote: "As entertainment, it does have a few moments of distinction, but on the whole it is a dull slow-paced piece, badly edited and mediocre in writing, direction and acting."[14] John McCarten of The New Yorker found that there was "nothing whatsoever in the footage that rises above the humdrum", and felt that Bergman "doesn't really seem to have her heart in any of the scenes."[15] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post lamented, "It's a pity that many people who never go to foreign-made pictures will be drawn into this by the Rossellini-Bergman names and will think that this flat, drab, inept picture is what they've been missing."[16]

In Britain, The Monthly Film Bulletin was also negative, writing that Rossellini's "extempore method is sadly out of place in a film dealing with personal relationships and, although there are indications that Karin is intended to be a complex and interesting character, these are never developed, and her motives and actions remain unpredictable. Other characters have no real identity, and hardly begin to come alive ... Ingrid Bergman makes a gallant effort with a part ill-conceived and scripted, and calling for a personality and quality which she cannot command."[17]

Recent assessments have been more positive. Reviewing the film in 2013 in conjunction with its DVD release as part of The Criterion Collection, Dave Kehr called the film "one of the pioneering works of modern European filmmaking."[8] In an expansive analysis of the film, critic Fred Camper wrote of the drama, "Like many of cinema's masterpieces, Stromboli is fully explained only in a final scene that brings into harmony the protagonist's state of mind and the imagery. This structure...suggests a belief in the transformative power of revelation. Forced to drop her suitcase (itself far more modest than the trunks she arrived with) as she ascends the volcano, Karin is stripped of her pride and reduced — or elevated — to the condition of a crying child, a kind of first human being who, divested of the trappings of self, must learn to see and speak again from a personal "year zero" (to borrow from another Rossellini film title)."[18]

The Venice Film Festival ranked Stromboli among the 100 most important Italian films ("100 film italiani da salvare") from 1942–1978. In 2012, the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound critics' poll also listed it as one of the 250 greatest films of all time.[19]

Box office

The film opened Feb. 15, 1950 in the United States[20] and was a box-office bomb, but did better overseas, where Bergman and Rossellini's affair was considered less scandalous. In all, RKO lost $200,000 on the picture.[21]

See also

- Strombolian eruption

- Almadraba — the tuna-fishing technique documented in the film

- The War of the Volcanoes — A 2012 Italian documentary film about the filming of Stromboli and Vulcano

References

- ^ "FILM 'STROMBOLI'S' BIG EARNINGS". The Morning Bulletin. Rockhampton, Qld. 24 February 1950. p. 1. Retrieved 21 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Harrison's Reports film review; February 18, 1950; page 26.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare Corriere della Sera". www.corriere.it. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ a b c d TCM: Stromboli – Notes Linked 2013-10-20

- ^ AFI Catalog of Feature Films: Stromboli – Notes Linked 2013-10-20

- ^ "Rossellini's 'Stromboli' Awarded Prize of Rome". Los Angeles Times: 21. March 13, 1950.

- ^ a b Dagrada, Elena. "A Triple Alliance for a Catholic Neorealism: Roberto Rossellini According to Felix Norton, Giulio Andreotti and Gian Luigi Rondi." Moralizing Cinema: Film, Catholicism, and Power. Eds. Daniel Biltereyst and Daniela Treveri Gennari. Routledge, 2014.

- ^ a b Kehr, Dave (September 27, 2013). "Rossellini and Bergman's Break From Tradition". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ "Storm over Stromboli". Time: 90. February 20, 1950.

- ^ "Senator Proposes U. S. Film Control". The New York Times: 33. March 15, 1950.

- ^ "'Stromboli' Gets Prize As Best Italian Film". The Washington Post: 5. March 13, 1950.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (February 16, 1950). "The Screen In Review". The New York Times: 28.

- ^ "Stromboli". Variety: 13. February 15, 1950.

- ^ "'Stromboli' with Ingrid Bergman". Harrison's Reports: 26. February 18, 1950.

- ^ McCarten, John (February 25, 1950). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 111.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (February 16, 1950). "All That Fuss, and The Thing Is Dull". The Washington Post: 12.

- ^ "Stromboli". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 17 (197): 83. June 1950.

- ^ Camper, Fred. Volcano Girl, film analysis and review. Chicago Reader, 2000. Last accessed: December 31, 2007.

- ^ "STROMBOLI, TERRA DI DIO (1950)". Archived from the original on 2012-08-20.

- ^ "Of Local Origin". New York Times. February 4, 1950.

- ^ Jewell, Richard B. (2016). Slow Fade to Black: The Decline of RKO Radio Pictures. University of California. p. 98. ISBN 9780520289673.

External links

- Stromboli at IMDb

- Stromboli at the TCM Movie Database

- Stromboli titles and selected scenes on YouTube

- lobby poster

- Modern Marriage on Stromboli an essay by Dina Iordanova at the Criterion Collection