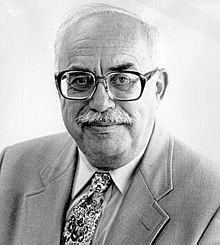

Stanford J. Shaw

Stanford J. Shaw | |

|---|---|

Stanford J. Shaw | |

| Born | Stanford Jay Shaw 5 May 1930 St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | 16 December 2006 (aged 76) Ankara, Turkey |

| Alma mater | Princeton University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ottoman history |

| Institutions | UCLA Bilkent University |

| Doctoral students | Heath Ward Lowry · Justin McCarthy |

Stanford Jay Shaw (5 May 1930 – 16 December 2006) was an American historian, best known for his works on the late Ottoman Empire, Turkish Jews, and the early Turkish Republic. Shaw's works have been criticized for their lack of factual accuracy as well as denial of the Armenian genocide, and other pro-Turkish bias.[1][2]

Biography

Stanford Jay Shaw was born to Belle and Albert Shaw, who had immigrated to St. Paul from England and Russia respectively in the early years of the twentieth century.[3] He was of Jewish heritage.[4][5] Stanford Shaw and his parents moved to Los Angeles, California, in 1933 because of his father's illness, and they lived there until 1939, first in Hollywood, where Stanford went to kindergarten, and then in Ocean Park, a community on the shore of the Pacific Ocean between Santa Monica and Venice, where his parents operated a photographic shop on the Ocean Park pier.[3]

The family returned to St. Paul in 1939, where Stanford went to the Webster Elementary School. After his parents divorced, Stanford went with his mother to Akron, Ohio during World War II, where he went to elementary school. Stanford and his mother remained there until she married Irving Jaffey and moved back to St. Paul. Stanford then attended Mechanic Arts High School in St. Paul, where he graduated in 1947, one out of only five students from a student body of 500 who went to college.[3]

Education and early research

He went on to Stanford University, where he majored in British history under the direction of Professor Carl Brand, with a minor in Near Eastern history, under the direction of Professor Wayne Vucinich. He received his B.A. at Stanford in 1951 and M.A. in 1952, with a thesis on the foreign policy of the British Labour Party from 1920–1938, based on research in the Hoover Institution at Stanford.[3]

He then studied Middle Eastern history along with Arabic, Turkish and Persian as a graduate student at Princeton University starting in 1952, receiving his M.A. in 1955. Subsequently he went to England to study with Bernard Lewis and Paul Wittek at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London and with Professor H. A. R. Gibb at Oxford University.

Following this, he went to Egypt to study with Shafiq Ghorbal and Adolph Grohmann at the University of Cairo and Shaikh Sayyid at the Azhar University, also doing research in the Ottoman archives of Egypt at the Citadel in Cairo for his Princeton Ph.D. dissertation concerning Ottoman rule in Egypt. Before leaving Egypt, he had a personal interview with President Gamal Abd al-Nasser, who arranged for him to take microfilms of Ottoman documents out of the country.[3]

Main research

In 1956-7 he studied at the University of Istanbul with Professors Omer Lutfi Barkan, Mukrimin Halil Yinanc, Halil Sahillioglu, and Zeki Velidi Togan, also completing research on his dissertation in the Ottoman archives of Istanbul, where he was helped by a number of staff members, including Ziya Esrefoglu, Turgut Isiksal, Rauf Tuncay, and Attila Cetin, and in the Topkapi Palace archives, where he was provided with valuable assistance and support by its director, Hayrullah Ors and studied with Professor İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı.

He received his Ph.D. degree in 1958 from Princeton University. His dissertation was titled "The Financial and Administrative Organization and Development of Ottoman Egypt, 1517–1798," which was prepared under the direction of Professor Lewis Thomas and Professor Hamilton A.R. Gibb, and later published by the Princeton University Press in 1962.[3] Stanford Shaw served as Assistant and Associate Professor of Turkish Language and History, with tenure, in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and in the Department of History at Harvard University from 1958 until 1968, and as Professor of Turkish history at the University of California Los Angeles from 1968 until his retirement in 1992.

Last years

He was recalled to teach Turkish history at UCLA between 1992 and 1997. His final post was at Bilkent University, Ankara, as professor of Ottoman and Turkish history from 1999 to 2006.[3]

The announcement of his death by his department at UCLA noted that his life was commemorated at Etz Ahayim Synagogue in Ortaköy, Istanbul, where his family accepted condolences from friends and colleagues and from Turkish Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül and numerous other dignitaries and that he was buried at the Ashkenazi Cemetery in Ulus.[6]

Awards

He was an honorary member of the Turkish Historical Society (Ankara), recipient of honorary degrees from Harvard University and the Boğaziçi University (Istanbul), and a member of the Middle East Studies Association, the American Historical Society, and the Tarih Vakfi (Istanbul). He also has received Order of Merit of the Republic of Turkey from the President of Turkey and medals for lifetime achievement from the Turkish-American Association and from the Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA) at the Yıldız Palace, Istanbul. He received two major research awards from the United States National Endowment from the Humanities as well as fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Fulbright-Hayes Committee. He was also a Senior Fellow of the Institute of Turkish Studies.[7]

Criticism

History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey

One of Shaw's most prominent works was a two-volume history on the Ottoman Empire, titled History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. The first volume, subtitled Empire of the Gazis: the Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire, 1280–1808, published in 1976, was met with generally mixed to negative reviews. Many faulted him for producing a work embellished with numerous historical errors and distortions. Colin Imber, a scholar on Ottoman history, noted in his review that both volumes were "so full of errors, half-truths, oversimplifications and inexactitudes that a non-specialist will find them positively misleading....When almost every page is a minefield of misinformation, a detailed review is impossible."[8] Another reviewer, Victor L. Ménage, Professor of Turkish at the University of London, counted over 70 errors in the work and concluded, "One 'prejudice' that has vanished in the process is the respect for accuracy, clarity, and reasoned judgment."[2]

In his extensive review of the first volume, Speros Vryonis, a specialist in Byzantine and Early Ottoman Studies at UCLA, listed a litany of problems he encountered in the work, such as Shaw's assertion that Sultan Mehmed II's forces did not subject Constantinople to a full scale sack and massacre upon its capture and his account of the treatment of the Greeks of Cyprus following the Ottoman conquest in 1571.[9] Vryonis also charged Shaw for largely failing to consult the proper primary sources of the period and therefore presenting a distorted picture of the formation of the Armenian and Greek/Eastern Orthodox millets.[10] Vryonis also stated that as much as 90% of the first volume had been lifted from the works of two Turkish historians and a Turkish-language encyclopedia.[11] UCLA declined to investigate the allegations of plagiarism.[11]

In the second volume of the History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, which Shaw co-authored with his wife, Ezel Kural Shaw, and which was published in 1977 with the subtitle Reform, Revolution, and Republic: the Rise of Modern Turkey, 1808–1975, the Shaws denied the Armenian genocide. Most scholars today believe that the events of 1915 constitute genocide.[12] However, according to Richard G. Hovannisian the Shaws characterize the Armenians as "the victimizers rather than the victims, as the privileged rather than the oppressed, and the fabricators of unfounded tales of massacre."[13] Hovannisian also criticized the book: "What could have been – what should have been – a valuable text is instead an unfortunate example of nonscholarly selectivity and deceptive presentation."[14][15]

In the bibliography of his general study on modern Turkey, Turkologist Eric J. Zürcher of the University of Leiden describes the second volume as "a mine of data," though the information not necessarily being accurate. He highlighted the Shaws' treatment of the reigns of Selim III and Abdülhamit II as the book's strongest parts, but observed that the last one hundred years it covers suffers from a "Turkish-nationalist bias."[16]

The second volume caused a stir among Armenian students attending UCLA and the Armenian community of Los Angeles at large. Matters came to a head when on the night of 3 October 1977, a bomb, placed by unknown assailants, exploded at the doorstep of Shaw's home at 3:50 a.m., although no one was hurt. A phone call placed several hours later by a man claimed that the Iranian Group of 28 was responsible for the bombing. Turkey's permanent ambassador to the UN disputed this, however, and alleged that Armenians were behind the attack.[17][18] Shaw made light of the situation and attributed the bombing to the fact that he had probably assigned too many F's. But he claimed that Armenian and Greek students had threatened him over the previous two years and canceled the rest of his classes for the remainder of the quarter.[19] With the controversy unabated ten years later, Shaw would claim Armenians were persecuting him not because of his scholarly views but for anti-Semitism, a charge that was disputed by Jewish organizations, including the UCLA chapter of Hillel, on campus, as well as a number of Jewish public figures and scholars.[20]

According to Yves Ternon, Shaw not only presented and published the Turkish version of the events of 1915-1916, he also used his academic and editorial influence to prevent the works of his opponents from being published in English: when he was a member of the reading committee of the University of California editions, the translation of a collection of documents proving the reality of the Armenian genocide was refused on the pretext that it was a propaganda pamphlet.[21]

Genocide scholar Israel W. Charny classifies Shaw as a Type 2 Genocide Denier, i.e presenting a "Malevolent Denial of the Facts of a Genocide and Innocent Disavowals of Violence", rather than Type 1, i.e presenting a "Malevolent Denial of the Facts of a Genocide and Celebration of Violence". Nevertheless, Charny notes that:

Shaw's work has been characterized as a "vehemently anti-Armenian and Hellenophobic interpretation of modern Turkish history," and it has been said that "he makes clear his identification with the genocidal policy of the Turkish republic that minorities (Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Kurds) would be tolerated only to the extent that they agreed to be virtually invisible...assimilating wholly into the Turkish nation." Shaw is so shoddy in his scholarship and so infuriating in his denials that one might argue that the metameaning of his work is indeed to celebrate the genocidal violence against the Armenians. Nonetheless, at this point, because of what I interpret as an overall absence of more direct statements celebrating the genocide, I classify him here in Type 2.[22]

The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic

In this book Shaw falsely claims, based on purported interviews, that Jews happily paid the 1942 Capital Tax, a discriminatory tax designed to financially ruin non-Muslim citizens of Turkey, and repeats the antisemitic discourse of Jews as war profiteers.[23]

Turkey and the Holocaust

In 1991, Shaw's study on the role of Turkey in providing refuge to the Jews of Europe in the years leading to and during the Holocaust was published.[24] Shaw claimed that the Republic of Turkey, as a neutral during the greater part of World War II, exerted its diplomatic efforts to the best of its abilities to save Jews of Turkish origins from extermination. The work was particularly receptive among Turkish government circles. It was, however, severely criticized by Bernard Wasserstein in The Times Literary Supplement for factual and methodological errors.[25] Wasserstein is aghast at Shaw's "tendency to ignore any negative evidence, while exaggerating the positive," for example, Shaw's claims that 90,000 Jewish refugees passed through Turkey on the way to Palestine, however, Wasserstein notes that this number is "150 percent of the total Jewish immigration, legal and illegal, to Palestine from all sources during the war". Wasserstein asks, "How can a supposedly professional historian arrive at such distorted, at times preposterous conclusions?"[25][22] Shaw's points have been challenged in a more recent study by Corry Guttstadt, who contests that his work has contributed to "an ossified, self-perpetuating myth [of Turkish utilitarianism] which is frequently propagated in international publications,"[26] and that Turkey, in fact, passed laws that prevented Jewish immigration and threatened to expel refugee academics if they lacked proper documentation (after their citizenship had been revoked by Nazi Germany).[27]

Historian Marc David Baer writes that the book was written with the help of Turkish career foreign service personnel and Turkish Jewish leaders. He states that the book " brought together Armenian genocide denial and an updated version of the centuries-old theme of utopian relations between Muslims and Jews in the face of the Christian enemy". Baer faults Shaw for relying on unverified statements by Turkish ambassadors to create a myth of Turkish heroism.[1]

Bibliography

- The Financial and Administrative Organization and Development of Ottoman Egypt, 1517–1798 (Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1962)

- Ottoman Egypt in the Age of the French Revolution (Harvard University Press, 1964)

- The Budget of Ottoman Egypt, 1005/06-1596/97 (Mouton and Co. The Hague, 1968)

- Between Old and New: The Ottoman Empire under Sultan Selim III. 1789–1807 (Harvard University Press, 1971)

- Ottoman Egypt in the Eighteenth Century (Harvard University Press)

- History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (2 volumes, Cambridge University Press, 1976–1977) (with Ezel Kural Shaw)

- The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic (Macmillan, London, and New York University Press, 1991)

- Turkey and the Holocaust: Turkey's role in rescuing Turkish and European Jewry from Nazi persecution, 1933–1945 (Macmillan, London and New York University Press, 1992)

- From Empire to Republic: The Turkish War of National Liberation 1918–1923: a documentary Study (I – V vols. in 6 books, TTK/Turkish Historical Society, Ankara, 2000)

- The Ottoman Empire in World War I, Ankara, TTK, two volumes, 2006–2008.

In addition to the above, Shaw was founder and first editor of the International Journal of Middle East Studies, published by the Cambridge University Press for the Middle East Studies Association, from 1970 until 1980.

Notes

- ^ a b Baer, Marc D. (2020). Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide. Indiana University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-253-04542-3.

- ^ a b Ménage, Victor L. "Review of History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 41 (1978): pp. 160–162.

- ^ a b c d e f g Profile of Prof. Shaw Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Bilkent University. Accessed 9 June 2011.

- ^ Baer, Marc D. (2020). Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 21, 145–146. ISBN 9780253045409.

- ^ Satan, Ali; Balcı, Meral (15 September 2017). Fatih Savaşan; Fatih Yardımcıoğlu; Mehmet Emin Altundemir; Furkan Beşel (eds.). "International Congress on Political, Economic, and Social Studies". Political Studies. 1. Sarajevo: Center for Political, Economic and Social Research: 75. ISBN 978-605-82738-7-0.

- ^ Wolf Leslau and Stanford J. Shaw: CNES mourns the passing of Professors Leslau and Shaw, UCLA Center for Near East Studies.

- ^ "Stanford J. Shaw: Biography." The Guardian. Accessed 9 June 2011.

- ^ Imber, Colin. "Review of History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey." The English Historical Review 93 (Apr. 1978): pp. 393–395.

- ^ Vryonis, Speros. Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Volume I: A Critical Analysis. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies, 1983.

- ^ Vryonis. A Critical Analysis, pp. 88–112.

- ^ a b Lecture delivered by Robert Hewsen. "Genocide Denial: Evolution of a Process" on YouTube, part of the 2007 Holocaust and Genocide Lecture Series at Sonoma State University (27:24 mark). 17 April 2007. Accessed 17 May 2011.

- ^ Why scholars say Armenian Genocide was genocide but Obama won't, Newsweek

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. "The Armenian Genocide and Patterns of Denial" in The Armenian Genocide in Perspective, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New Brunswick, NJ: Transactions Publishers, 1986, p. 125.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. "The Critic's View: Beyond Revisionism." International Journal of Middle East Studies 9 (October 1978): pp. 379–388. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ For the Shaws' response, see Stanford J. Shaw and Ezel Kural Shaw, "The Authors Respond." International Journal of Middle East Studies 9 (October 1978): pp. 388–400.

- ^ Zürcher, Eric J. Turkey: A Modern History, 3rd. Ed. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004, p. 360.

- ^ Manoukian, Socrates Peter; Kurugian, John O. (4 October 1977). "Crude Bomb Explodes at UCLA Professor's Home" (PDF). Los Angeles Times. pp. D1 (Part II). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ^ Manoukian, Socrates Peter; Kurugian, John O. (18 October 1977). "Shaw Bomb" (PDF). Los Angeles Times. pp. C6 (Part II). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ^ Daily Bruin. 4 October 1977, p. 1.

- ^ Arkun, Aram. "Stanford Jay Shaw, 1930–2006: An academic who denied the Armenian Genocide." The Armenian Reporter. 23 December 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Y. Ternon, La Cause arménienne. p. 252 (note 2).

- ^ a b Charny, Israel W. (1 April 2000). "Innocent denials of known genocides: A further contribution to a psychology of denial of genocide". Human Rights Review. 1 (3): 15–39. doi:10.1007/s12142-000-1019-6. ISSN 1874-6306. S2CID 144586638.

- ^ Baer, Marc D. (2020). Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide. Indiana University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-253-04542-3.

It also serves to counter Shaw's humiliating contention—based on purported interviews that he cites nowhere of events that have been contradicted by scholars in Turkey and abroad and by the published accounts of Turkish Jews who experienced that era—that Jews happily paid the tax, which 'helped the Jews of Turkey by showing Turks that the Jews were suffering so much that they should not give in to Nazi demands to deport their Jews to the death camps.' How could Shaw claim that Jews happily paid an unfair tax that ruined them financially and psychologically? Many Jews unable to pay the tax who served at the labor camps in Aşkale returned broken men. Some died there. Not only is Shaw's statement unattributed to any source, but it is also factually inaccurate; the Nazis never demanded that Turkey deport its Jews to death camps. Moreover, adding that 'the deprivation of their wealth by the government drained what resentment there might otherwise have been among Turks against Jewish wealth while the mass of the population was suffering because of the war,' Shaw repeats the anti-Semitic campaign at the time depicting Jews as war profiteers.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford. Turkey and the Holocaust: Turkey's Role in Rescuing Turkish and European Jewry from Nazi Persecution, 1933–1945. New York: New York University Press, 1993.

- ^ a b Wasserstein, Bernard (7 January 1994). "Their Own Fault – Attempts to shift the blame for the Holocaust". The Times Literary Supplement: 4–6.

- ^ Guttstadt, Corry. Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, p.1.

- ^ Von Bieberstein, Alice. "'Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust,' By Corry Guttstadt." Turkish Review. 2 January 2014.

External links

- Profile, Bilkent University, Turkey

- Stanford J. Shaw at Library of Congress, with 13 library catalog records (under 'Shaw, ... 1930–' without '2006', previous page of browse report)

- Ezel Kural Shaw at LC Authorities, with 2 records