Scelidotherium

| Scelidotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| S. leptocephalum Skeletal mount in the National Museum of Natural History (France) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Scelidotheriidae |

| Genus: | †Scelidotherium Owen, 1840 |

| Species | |

| |

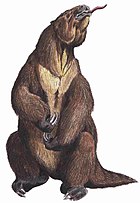

Scelidotherium is an extinct genus of ground sloth of the family Scelidotheriidae, endemic to South America during the Late Pleistocene epoch. It lived from 780,000 to 11,000 years ago, existing for approximately 0.67 million years.[1]

Description

It is characterized by an elongated, superficially anteater-like head. In fossil distribution, it is known from Argentina (Luján and Arroyo Seco Formations), Bolivia (Tarija Formation), Peru (San Sebastián Formation), Panama, Brazil, Paraguay and Ecuador.[1]

In his journal of The Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin reports the finding of a nearly perfect fossil Scelidotherium in Punta Alta while travelling overland from Bahía Blanca to Buenos Aires in 1832. He allied it to the Megatherium. Owen (1840) recognized the true characters of the remains and named them Scelidotherium, which means "femur beast" to reflect the distinctive proportions of that skeletal element. They were 1.1 metres (3.6 ft) tall and might have weighed up to 850 kg (1,870 lb).[2]

Taxonomy

Scelidotherium was named by Owen (1840). It was assigned to Mylodontidae by Carroll (1988); and to Scelidotheriinae by Gaudin (1995) and Zurita et al. (2004).[3] Scelidotheriinae was elevated back to full family status by Presslee et al. (2019).[4]

Gallery

-

Front view of Scelidotherium leptocephalum skeleton

-

Scelidotherium sp. incomplete right hand

-

Scelidotherium skull in situ in plaster jacket, Argentina, 1926. Collected on the second Marshall Field Paleontological Expedition.

References

- ^ a b "Scelidotherium in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Bargo, MS, SF Vizcaíno, FM Archuby, and RE Blanco. 2000. Limb bone proportions, strength and digging in some Lujanian (Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene) Mylodontid ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 20(3):601-610

- ^ R. L. Carroll. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York 1-698

- ^ Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3.1121P. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

Further reading

- Owen, R. (1840) Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle1, Fossil Mammalia.