Richard Neutra

Richard Neutra | |

|---|---|

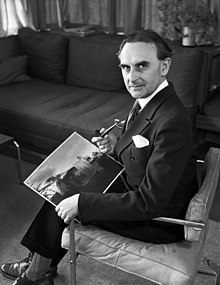

Neutra with a photo of the Beard House, 1935 | |

| Born | Richard Joseph Neutra April 8, 1892 |

| Died | April 16, 1970 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse |

Dione Niedermann

(m. 1922–1970) |

| Children | 3, including Dion Neutra (1926-2019) |

| Awards | Wilhelm Exner Medal (1959) AIA Gold Medal (1977) |

Richard Joseph Neutra (/ˈnɔɪtrə/ NOI-tra;[1] April 8, 1892 – April 16, 1970) was an Austrian-American architect. Living and building for most of his career in Southern California, he came to be considered a prominent and important modernist architect.[2][3] His most notable works include the Kaufmann Desert House, in Palm Springs, California.

Biography

Neutra was born in Leopoldstadt, the second district of Vienna, Austria Hungary, on April 8, 1892, into a wealthy Jewish family. His Jewish-Hungarian father Samuel Neutra (1844–1920),[4][5] was a proprietor of a metal foundry, and his mother, Elizabeth "Betty" Glaser[6] Neutra (1851–1905) was a member of the IKG Wien. Richard had two brothers, who also emigrated to the United States, and a sister, Josephine Theresia "Pepi" Weixlgärtner, an artist who married the Austrian art historian Arpad Weixlgärtner and who later emigrated to Sweden. Her work can be seen at the Modern Art Museum in Stockholm.[7]

Neutra attended the Sophiengymnasium in Vienna until 1910. He studied under Max Fabiani and Karl Mayreder at the Vienna University of Technology (1910–18) and also attended the private architecture school of Adolf Loos. In 1912, he undertook a study trip to Italy and the Balkans with Ernst Ludwig Freud (son of Sigmund Freud).[citation needed]

In June 1914, Neutra's studies were interrupted when he was ordered to Trebinje, where he served as an lieutenant in the artillery until the end of World War I. Dione Neutra recalled her husband Richard's hatred of the retribution against the Serbs in an interview conducted in 1978 after his death: "He talked about the people he met [i.e. in Trebinje] … how his commander was a sadist, who was able to play out his sadistic tendencies…. He was just a small town clerk in Vienna, but then he became his commander."[8]

Neutra took a leave in 1917 to return to the Technische Hochschule to take his final examinations.[9]

After World War I, Neutra moved to Switzerland, where he worked with the landscape architect Gustav Ammann. In 1921, he served briefly as city architect in the German town of Luckenwalde, and later in the same year he joined the office of Erich Mendelsohn in Berlin. Neutra contributed to the firm's competition entry for a new commercial center for Haifa, Palestine (1922), and to the Zehlendorf housing project in Berlin (1923).[10] He married Dione Niedermann, the daughter of an architect, in 1922. They had three sons, Frank L (1924–2008), Dion (1926–2019), who became an architect and his father's partner, and Raymond Richard Neutra (1939–), a physician and environmental epidemiologist.

Richard Neutra moved to the United States by 1923 and became a naturalized citizen in 1929. He worked briefly for Frank Lloyd Wright before accepting an invitation from Rudolf Schindler, a close friend from his university days, to work and live communally in Schindler's Kings Road House in California. Neutra's first works in California were both in the realm of landscape architecture: namely, the grounds of the Lovell Beach House (1922–25), in Newport Beach, which Schindler had designed for Philip Lovell; and a pergola and wading pool for the complex that Wright and Schindler had designed for Aline Barnsdall on Olive Hill (1925), in Hollywood. Schindler and Neutra would go on to collaborate on an entry for the League of Nations Competition (1926–27); in the same year, they formed a firm with the planner Carol Aronovici (1881–1957), called the Architectural Group for Industry and Commerce (AGIC). Neuatra subsequently developed his own practice and went on to design numerous buildings embodying the International Style, 12 of which are designated as Historic Cultural Monuments (HCM), including the Lovell Health House (HCM #123; 1929), for the same client as the Lovell Beach House, and the Richard and Dion Neutra VDL Research House (HCM #640; 1966).[10] In California, he became celebrated for rigorously geometric but airy structures that epitomized a West Coast version of mid-century modern residential design. His clients included Edgar J. Kaufmann, (who had commissioned Wright to design Fallingwater, in Pennsylvania), Galka Scheyer, and Walter Conrad Arensberg. In the early 1930s, Neutra's Los Angeles practice trained several young architects who went on to independent success, including Gregory Ain, Harwell Hamilton Harris, and Raphael Soriano. In 1932, he tried to move to the Soviet Union, to help design workers' housing that could be easily constructed, as a means of helping with the housing shortage.[11]

In 1932, Neutra was included in the seminal MoMA exhibition on modern architecture, curated by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock. From 1943 to 1944, Neutra served as a visiting professor of design at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont. In 1949 Neutra formed a partnership with Robert E. Alexander that lasted until 1958, which finally gave him the opportunity to design larger commercial and institutional buildings. In 1955, the United States Department of State commissioned Neutra to design a new embassy in Karachi. Neutra's appointment was part of an ambitious program of architectural commissions to renowned architects, which included embassies by Walter Gropius in Athens, Edward Durrell Stone in New Delhi, Marcel Breuer in The Hague, Josep Lluis Sert in Baghdad, and Eero Saarinen in London. In 1965, Neutra formed a partnership with his son Dion Neutra.[10] Between 1960 and 1970, Neutra created eight villas in Europe, four in Switzerland, three in Germany, and one in France. Prominent clients in this period included Gerd Bucerius, publisher of Die Zeit, as well as figures from commerce and science. His work was also part of the architecture event in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics.[12]

Richard Joseph Neutra died on April 16, 1970, at the age of 78.[13]

Architectural style

He was known for the attention he gave to defining the real needs of his clients, regardless of the size of the project, in contrast to other architects eager to impose their artistic vision on a client. Neutra sometimes used detailed questionnaires to discover his client's needs, much to their surprise. His domestic architecture was a blend of art, landscape, and practical comfort.[citation needed]

In a 1947 article for the Los Angeles Times, "The Changing House," Neutra emphasizes the "ready-for-anything" plan – stressing an open, multifunctional plan for living spaces that are flexible, adaptable and easily modified for any type of life or event.[14]

Neutra had a sharp sense of irony. In his autobiography, Life and Shape, he included a playful anecdote about an anonymous movie producer-client who electrified the moat around the house that Neutra designed for him and had his Persian butler fish out the bodies in the morning and dispose of them in a specially designed incinerator. This was a much-embellished account of an actual client, Josef von Sternberg, who indeed had a moated house but not an electrified one.[citation needed]

The novelist/philosopher Ayn Rand was the second owner of the Von Sternberg House in the San Fernando Valley (now destroyed). A photo of Neutra and Rand at the home was taken by Julius Shulman.[citation needed]

Neutra's early watercolors and drawings, most of them of places he traveled (particularly his trips to the Balkans in WWI) and portrait sketches, showed influence from artists such as Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele etc. Neutra's sister Josefine, who could draw, is cited as developing Neutra's inclination towards drawing.[citation needed]

Legacy

Neutra's son Dion has kept the Silver Lake offices designed and built by his father open as "Richard and Dion Neutra Architecture" in Los Angeles. The Neutra Office Building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[14]

In 1980, Neutra's widow donated the Van der Leeuw House (VDL Research House), then valued at $207,500, to California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (Cal Poly Pomona) to be used by the university's College of Environmental Design faculty and students.[15][16] In 2011, the Neutra-designed Kronish House (1954) at 9439 Sunset Boulevard in Beverly Hills sold for $12.8 million.[17]

In 2009, the exhibition "Richard Neutra, Architect: Sketches and Drawings" at the Los Angeles Central Library featured a selection of Neutra's travel sketches, figure drawings and building renderings. An exhibition on the architect's work in Europe between 1960 and 1979 was mounted by the MARTa Herford, Germany.[citation needed]

The Kaufmann Desert House was restored by Marmol Radziner + Associates in the mid-1990s.[18]

The typeface family Neutraface, designed by Christian Schwartz for House Industries, was based on Richard Neutra's architecture and design principles.[citation needed]

In 1977, he was posthumously awarded the AIA Gold Medal, and in 2015, he was honored with a Golden Palm Star on the Walk of Stars in Palm Springs, California.[19]

Lost works

Neutra's 14,000 sqf "Windshield" house built on Fishers Island, NY for John Nicholas Brown II burned down on New Year's Eve 1973 and was not rebuilt.[20]

The 1935 Von Sternberg House in Northridge, California was demolished in 1972.[21]

Neutra's 1960 Fine Arts Building at California State University, Northridge was demolished in 1997, three years after suffering severe damage in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.[22][23]

The 1962 Maslon House in Rancho Mirage, California, was demolished in 2002.[24]

Neutra's Cyclorama Building at Gettysburg was demolished by the National Park Service in March 2013.[25]

The Slavin House (1956) in Santa Barbara, California was destroyed in a fire in 2001.[26]

Selected works

- Jardinette Apartments, 1928, 5128 Marathon Street, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California

- Lovell House, 1929, Los Angeles, California

- Van der Leeuw House (VDL Research House), 1932, Los Angeles, California

- Mosk House, 1933, 2742 Hollyridge Drive, Hollywood, California

- Nathan and Malve Koblick House, 1933, 98 Fairview Avenue, Atherton, California

- Universal-International Building (Laemmle Building), 1933, 6300 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood, Los Angeles, California

- Scheyer House, 1934, 1880 Blue Heights Drive, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California

- William and Melba Beard House (with Gregory Ain), 1935, 1981 Meadowbrook, Altadena

- California Military Academy, 1935, Culver City, California

- Corona Avenue Elementary School, 1935, 3835 Bell Avenue, Bell, California

- Largent House, 1935, 49 Hopkins Avenue at the corner of Burnett Avenue, San Francisco. Building was demolished by new owners and as of 2018[update], they have been ordered to rebuild an exact replica.[27][28]

- Von Sternberg House, 1935, San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles

- Sten and Frenke House (Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #647), 1934, 126 Mabery Road, Santa Monica

- The Neutra House Project, 1935, Restoration of the Neutra "Orchard House" in Los Altos, California

- Josef Kun House, 1936, 7960 Fareholm Drive, Nichols Canyon, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California[29]

- Darling House,[30] 1937, 90 Woodland Avenue, San Francisco, California

- George Kraigher House, 1937, 525 Paredes Line Road, Brownsville, Texas

- Landfair Apartments, 1937, Westwood, Los Angeles, California

- Strathmore Apartments, 1937, Westwood, Los Angeles, California

- Aquino Duplex, 1937, 2430 Leavenworth Street, San Francisco

- Leon Barsha House (with P. Pfisterer), 1937, 302 Mesa Road, Pacific Palisades, California

- Miller House,[31] 1937, Palm Springs, California

- Windshield House,[32] 1938, Fisher's Island, New York

- Albert Lewin House, 1938, 512-514 Palisades Beach Road, Santa Monica, Los Angeles

- Emerson Junior High School, 1938, 1650 Selby Avenue, West Los Angeles, California

- Ward-Berger House, 1939, 3156 North Lake Hollywood Drive, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California

- Kelton Apartments, Westwood, Los Angeles

- Sidney Kahn House, 1940, Telegraph Hill, San Francisco

- Beckstrand House, 1940, 1400 Via Montemar, Palos Verdes Estates, Los Angeles County

- Bonnet House, 1941, 2256 El Contento Drive, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California

- Neutra/Maxwell House, 1941, 475 N. Bowling Green Way, Brentwood, Los Angeles (Moved to Angelino Heights in 2008.)

- Van Cleef Residence, 1942, 651 Warner Avenue, Westwood, Los Angeles

- Geza Rethy House, 1942, 2101 Santa Anita Avenue, Sierra Madre, California

- Channel Heights Housing Projects, 1942, San Pedro, California

- John Nesbitt House, 1942, 414 Avondale, Brentwood, Los Angeles

- Kaufmann Desert House,[33][34][35] 1946, Palm Springs, California

- Stuart Bailey House, 1948, Pacific Palisades, California (Case Study 20A)

- Case Study Houses #6, #13, #20A, #21A

- Schmidt House, 1948, 1460 Chamberlain Road, Linda Vista, Pasadena, California

- Joseph Tuta House, 1948, 1800 Via Visalia, Palos Verdes, California

- Holiday House Motel, 1948, 27400 Pacific Coast Highway, Malibu, California

- Elkay Apartments, 1948, 638-642 Kelton Avenue, Westwood, Los Angeles

- Gordon Wilkins House, 1949, 528 South Hermosa Place, South Pasadena, California[36][37]

- Alpha Wirin House, 1949, 2622 Glendower Avenue, Los Feliz, Los Angeles

- Hines House, 1949, 760 Via Somonte, Palos Verdes, California

- Atwell House, 1950, 1411 Atwell Road, El Cerrito, California

- Nick Helburn House, 1950, Sourdough Road, Bozeman, Montana

- Neutra Office Building — Neutra's design studio from 1950 to 1970

- Kester Avenue Elementary School, 5353 Kester Avenue, Los Angeles (with Dion Neutra), 1951, Sherman Oaks, California

- Everist House, 1951, 200 W. 45th Street, Sioux City, Iowa[38]

- Moore House, 1952, Ojai, California (received AIA award)

- Perkins House, 1952–55, 1540 Poppypeak Drive, Pasadena, California

- Schaarman House, 1953, 7850 Torreyson Drive, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California

- Olan G. and Aida T. Hafley House, 1953, 5561 East La Pasada Street, Long Beach[39]

- Brown House, 1955, 10801 Chalon Road, Bel Air, Los Angeles

- Kronish House, 1955, Beverly Hills, California[40]

- Sidney R. Troxell House,[41] 1956, 766 Paseo Miramar, Pacific Palisades, California

- Chuey House, 1956, 2460 Sunset Plaza Drive, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California[42][43]

- Clark House, 1957, Pasadena, California

- Airman's Memorial Chapel, 1957, 5702 Bauer Road, Miramar, California

- Sorrell's House, 1957, Old State Highway 127, Shoshone, California[44]

- Ferro Chemical Company Building, 1957, Cleveland, Ohio

- The Lew House, 1958, 1456 Sunset Plaza Drive, Los Angeles

- Connell House, 1958, Pebble Beach, California

- Mellon Hall and Francis Scott Key Auditorium, 1958, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland

- Riviera United Methodist Church, 1958, 375 Palos Verdes Boulevard, Redondo Beach

- Loring House, 1959, 2456 Astral Drive, Los Angeles (addition by Escher GuneWardena Architecture, 2006

- Singleton House, 1959, 15000 Mulholland Drive, Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, California

- Oyler House, 1959 Lone Pine, California

- UCLA Lab School, 1959 (with Robert Alexander)[45]

- Garden Grove Community Church, Community Church, 1959 (Fellowship Hall and Offices), 1961 (Sanctuary), 1968 (Tower of Hope), Garden Grove, California

- Three senior officer's quarters on Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho, 1959

- Julian Bond House, 1960, 4449 Yerba Santa, San Diego, California

- R.J. Neutra Elementary School, 1960, Naval Air Station Lemoore, in Lemoore, California (designed in 1929)

- Buena Park Swim Stadium and Recreation Center, 1960, 7225 El Dorado Drive, Buena Park, California[46]

- Palos Verdes High School, 1961, 600 Cloyden Road, Palos Verdes, California

- Haus Rang, 1961, Königstein im Taunus, Germany

- Hans Grelling House/Casa Tuia on Monte Verità, 1961, Strada del Roccolo 11, Ascona, Tessin, Switzerland

- Los Angeles County Hall of Records, 1962, Los Angeles, California.

- Gettysburg Cyclorama, 1962, Gettysburg National Military Park, Pennsylvania

- Gonzales Gorrondona House, 1962, Avenida la Linea 65, Sabana Grande, Caracas, Venezuela

- Bewobau Residences, 1963, Quickborn near Hamburg, Germany

- Mariners Medical Arts, 1963, Newport Beach, California

- Painted Desert Visitor Center, 1963, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

- United States Embassy, (later US Consulate General until 2011), 1959, Abdullaha Haroon Road, Karachi, Pakistan[47]

- Swirbul Library, 1963, Adelphi University, Garden City, New York

- Kuhns House, 1964, Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, California

- Rice House (National Register of Historic Places), 1964, 1000 Old Locke Lane, Richmond, Virginia

- VDL II Research House,[48][49][50] 1964, (rebuilt with son Dion Neutra) Los Angeles, California

- Rentsch House, 1965, Wengen near Berne in Switzerland; Landscape architect: Ernst Cramer

- Ebelin Bucerius House, 1962–1965, Brione sopra Minusio in Switzerland; Landscape architect: Ernst Cramer

- Roberson Memorial Center, 1965, Binghamton, New York

- Haus Kemper, 1965, Wuppertal, Germany

- Sports and Congress Center, 1965, Reno, Nevada

- Delcourt House, 1968–69, Croix, Nord, France

- Haus Pescher, 1969, Wuppertal, Germany

- Haus Jürgen Tillmanns, 1970, Stettfurt, Thurgau, Switzerland

-

Cyclorama Building, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

-

Jardinette Apartments, Hollywood

-

Kaufmann Desert House, Palm Springs, California.

-

Garden Grove Community Church, Garden Grove, CA

-

The former US embassy (later consulate) in Karachi, Pakistan

Publications

- 1927: Wie Baut Amerika? (How America Builds) (Julius Hoffman)

- 1930: Amerika: Die Stilbildung des neuen Bauens in den Vereinigten Staaten (Anton Schroll Verlag). New Ways of Building in the World [series], vol. 2. Edited by El Lissitzky.

- 1935: "New Elementary Schools for America". Architectural Forum. 65 (1): 25–36. January 1935.

- 1948: Architecture of Social Concern in Regions of Mild Climate (Gerth Todtman)

- 1951: Mystery and Realities of the Site (Morgan & Morgan)

- 1954: Survival Through Design (Oxford University Press)

- 1956: Life and Human Habitat (Alexander Koch Verlag).

- 1961: Welt und Wohnung (Alexander Kock Verlag)

- 1962: Life and Shape: an Autobiography (Appleton-Century-Crofts), reprinted 2009 (Atara Press)

- 1962: Auftrag für morgen (Claassen Verlag)

- 1962: World and Dwelling (Universe Books)

- 1970: Naturnahes Bauen (Alexander Koch Verlag)

- 1971: Building With Nature (Universe Books)

- 1974: Wasser Steine Licht (Parey Verlag)

- 1977: Bauen und die Sinneswelt (Verlag der Kunst)

- 1989: Nature Near: The Late Essays of Richard Neutra (Capra Press)

References

- ^ Dorsey, Michael (2012). The Oyler House: Richard Neutra's Desert Retreat (Motion picture). First Run Features.

- ^

Bevan, Alex (February 7, 2019) [2018]. The Aesthetics of Nostalgia TV: Production Design and the Boomer Era. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA (published 2019). ISBN 9781501331435. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

[...] Richard Neutra (a Californian prominent modernist architect) [...].

- ^

Burton, Pamela; Botnick, Marie; Smith, Kathryn (2002). "The Pavilion in the Garden". Private Landscapes: Modernist Gardens in Southern California. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781568984025. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

It was because of [Wright] that Schindler and Neutra, two important modern architects, came to Los Angeles.

- ^ "Chronicles of Brunonia" (PDF). Dl.lib.brown.edu. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ "1837/L". .sympatico.ca. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ or Glazer

- ^ "Collection of prints by Pepi Weixlgärtner-Neutra, 1938-1960". researchworks.oclc.org. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Carmichael, Cathie (September 3, 2018). "Culture, resistance and violence: guarding the Habsburg Ostgrenze with Montenegro in 1914". European Review of History. 25 (5): 705–723. doi:10.1080/13507486.2018.1474179.

- ^ Esther McCoy.(1974).Letters between R. M. Schindler and Richard Neutra, 1914-1924.Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 33, No. 3 (October 1974), pp.219–224

- ^ a b c "Richard Neutra". MoMA. February 22, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ State Archive of the Russian Federation, f R7544, op 1, d 78, l 6

- ^ "Richard Neutra". Olympedia. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Richard Joseph Neutra | Austrian-American architect". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Neutra, Dion (2012). "The Neutras Then & Later(Photography by Julius Shulman". I (I). Triton: Barcelona, Los Angeles.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Cal Poly Pomona Given Neutra Research House". Los Angeles Times. March 2, 1980.

- ^ "Architect's Home Given To Cal Poly". Los Angeles Times. May 18, 1980.

- ^ Lauren Beale (October 14, 2011), Richard Neutra-designed Kronish house sells for $12.8 million Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ho, Vivien (October 21, 2020) Modernist architectural marvel made famous by Slim Aarons for sale for $25m. Retrieved October 25, 2020

- ^ Palm Springs Walk of Stars official website Archived October 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernstein, Fred (February 3, 2002). "ART/ARCHITECTURE; When Modern Married Money". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ Hines, Thomas S. (May 31, 2004). "Richard Neutra". Architectural Digest. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Richard Neutra's Fine Arts Building". Peek in the Stacks. March 30, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Vitucci, Claire (July 18, 1997). "Cal State Northridge Razes Neutra Building". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Dunning, Brad (April 21, 2002). "A Destruction Site". The New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Stansbury, Amy (March 9, 2013). "The death of the Gettysburg Cyclorama building". The Evening Sun. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Pridgen, Andrew (July 17, 2022). "How a legendary mid-century modern home came to languish in one of California's hottest real estate markets". SFGATE.

- ^ Dineen, J.K. (December 15, 2018). "SF to developer who tore down landmark house: Rebuild it exactly as it was". SF Chronicle. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "US owner ordered to build replica house". BBC News. December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Jao, Carren (November 21, 2014) "Devo rocker's new trio works to restore Neutra's Kun House" Los Angeles Times

- ^ "90 Woodland Ave, San Francisco, CA 94117 - 3 beds/1.5 baths". Redfin. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Leet, Stephen; Shulman, Julius (2004). Richard Neutra's Miller House. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1568982748. LCCN 2003021531. OCLC 473973008.

- ^ Neumann, Dietrich, ed. (2001). Richard Neutra's Windshield House. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09203-2.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (October 31, 2007). "A Landmark Modernist House Heads to Auction". New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ Judith Gura (May 1, 2008). "Richard Neutra's Kaufmann House". ARTINFO. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Friedman, Alice T. (c. 2010). "2. Palm Springs Eternal: Richard Neutra's Kaufmann Desert House". American Glamour and the Evolution of Modern Architecture. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0300116540. LCCN 2009032574.

- ^ "Richard Neutra – NCMH Modernist Masters Gallery". Trianglemodernisthouses.com. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived April 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Everist House Multiple Views (1951)". neutra.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Carol Crotta (May 2, 2015), Neutra restoration in Long Beach honors time and patina Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Transitions". Preservation. 64 (1). National Trust for Historic Preservation: 6. January 2012.

- ^ "Troxell Residence v.2". www.landliving.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2006.

- ^ Lavin, Sylvia (2004). Form Follows Libido: Architecture and Richard Neutra in a Psychoanalytic Culture. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-12268-5.

- ^ Zara, Janelle (April 6, 2020). "Inside Richard Neutra's Historic Chuey House". Architectural Digest. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ SAHSCC. "Modern Patrons: Neutra In Shoshone". Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "University Elementary School | Los Angeles Conservancy".

- ^ Hines, Thomas S. (2006). Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture (4 ed.). Rizzoli. p. 316. ISBN 978-0847827633. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Obituary For A Consulate Office Building January 19, 2011, Retrieved March 31, 2011

- ^ Eastman, Janet (April 17, 2008). "The clock is ticking for Richard Neutra's VDL Research House II". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ Ayyüce, Orhan (March 17, 2008). "Neutra's VDL House; v. Hard Times". archinect.com. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ "Creative Decorating Ideas". NeutraVDL.org. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

Other sources

- McCoy, Esther (1960). Five California Architects. Reinhold Publishing. ISBN 0-275-71720-8.

- reprinted in 1975 by Praeger

- Hines, Thomas (1982). Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503028-1.

- reprinted in 1994 by the University of California Press

- reprinted in 2006 by Rizzoli Publications

- Lavin, Sylvia (December 1999). "Open the Box: Richard Neutra and the Psychology of the Domestic Environment". Assemblage. 40 (40). The MIT Press: 6–25. doi:10.2307/3171369. JSTOR 3171369.

- Lamprecht, Barbara (2000). Richard Neutra: Complete Works. Taschen. p. 360. ISBN 978-3822866221.

- Lamprecht, Barbara (2004). Richard Neutra, 1892–1970: Survival through Design. Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-2773-8.

- Lavin, Sylvia (2005). Form Follows Libido: Architecture and Richard Neutra in a Psychoanalytic Culture. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-12268-5.

- Cronan, Todd (July 2011). "Danger in the Smallest Dose: Richard Neutra's Design Theory". Design and Culture. 3 (2). Berg Publishers: 165–191. doi:10.2752/175470811X13002771867806. S2CID 144862490. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- Neutra, Dion (2012). The Neutras Then & Later I (Photography by Julius Shulman). Triton: Barcelona, Los Angeles. ISBN 978-84-938482-7-9.

Publications on Richard Neutra:

- Harriet Roth; Richard Neutra in Berlin, Die Geschichte der Zehlendorfer Häuser, Berlin 2016. Hatje Cantz publishers.

- Harriet Roth; Richard Neutra. The Story of the Berlin Houses 1920–1924, Berlin 2019. Hatje Cantz publishers.

- Harriet Roth; Richard Neutra. Architekt in Berlin, Berlin 2019. Hentrich&Hentrich publishers.

External links

- Finding Aid for the Richard and Dion Neutra Papers, UCLA Library Special Collections.

- Digitized plans, sketches, photographs, texts from the Richard and Dion Neutra Collection, UCLA Library Special Collections.

- Jan De Graaff Residence architectural drawings and photographs, circa 1940sHeld by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

- Richard Joseph Neutra papers, 1927-1978 Held in the Dept. of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York City

- Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design (NISTD)

- Neutra at GreatBuildings.com

- Neutra at modernsandiego.com

- Neutra biography at r20thcentury.com

- Info and photos from Winkens.ie

- History, plans and photographs of the VDL I & VDL II Research Houses

- Neutra VDL Studio and Residences iPad App

- Richard Neutra and the California Art Club: Pathways to the Josef von Sternberg and Dudley Murphy Commissions

- R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra and Louis Sullivan's "Kindergarten Chats"

- Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad

- Richard Joseph Neutra papers, 1927-1978, held by the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

- Finding aid for Thomas S. Hines interviews regarding Richard J. Neutra. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Accession No. 2010.M.58. Interviewees include Neutra's family, friends, business associates, clients, and Los Angeles architects.