Regalia of the Pharaoh

The Regalia of the Pharaoh or Pharaoh's attributes are the symbolic objects of royalty in ancient Egypt (crowns, headdresses, scepters). In use between 3150 and 30 BC, these attributes were specific to pharaohs, but also to certain gods such as Atum, Ra, Osiris and Horus. In Egyptian mythology, these powerful gods were considered the original holders of royal power and the first rulers of the Nile Valley.

As successor to the gods, the pharaoh never appeared bareheaded in public, given his sacrosanct function. In Egyptian iconography, royal attributes appeared as early as the dawn of civilization. As early as the First Dynasty, the white crown of Upper Egypt, in the shape of an elongated mitre, was commonly worn by sovereigns. The same is true of the mortar-shaped red crown of Lower Egypt, and the pschent double-crown. The latter was sometimes adapted to the nemes headdress, a pleated, striped cloth. Later, the blue khepresh headdress was quite common in the New Kingdom. A powerful symbol of protection, the snake-uraeus inevitably encircled the royal brow on all occasions.

The scepters were other symbols of domination. The scepter-heqa and the flagellum-nekhekh, with their pastoral aspects, demonstrated that the Pharaoh was the shepherd of his people, guiding and protecting them.

Other attributes include the bull's tail attached to the back of the loincloth, the ceremonial beard, sandals and the mekes case.

Overview

Throughout the history of Pharaonic Egypt, crowns, scepters, canes and other royal accessories such as scarves, sandals, loincloths and ceremonial beards played a dual role of protection and power. Very prosaically, these objects served to distinguish the Pharaoh from other human beings. All these sacred objects also conferred on their bearer civil authority as supreme commander of the state administration, military authority as head of the armies and religious authority as earthly representative of the gods.[1]

Each regalia carried its own symbolic significance. Each one was a powerful magical amulet whose role was to protect the pharaoh from all danger and to ward off the hostile forces that haunted the universe (invisible demons, Egyptian rebels, enemy countries).[2]

Some of these objects pre-date the foundation of the Egyptian state, and were already attested in the Predynastic period. Others were added during the First Dynasty. During the Second Dynasty, their functions became more formalized, remaining practically unchanged for the three millennia of Pharaonic kingship.[3]

Crowns

The Pharaoh shared with the major deities the privilege of wearing crowns. These sacred headdresses were many and varied, and some were complex compositions combining horns, high feathers and uraeus (hemhem, atef, wereret, henu crowns, etc.).[4] The three royal crowns were the most sober. The white crown was shaped like an elongated mitre, ending in a bulb.[5] The red crown resembled a mortarboard, with the rear part rising to the top and a stem ending in a spiral; the khabet.[6] From the First Dynasty onwards, these two crowns came to represent the royalty of Upper and Lower Egypt respectively. Symbolizing the South and not unrelated to the annual flooding of the Nile, the white crown was worn by the vulture goddess Nekhbet and by Osiris, the murdered god whose lymphs were responsible for the Nile flood.[5] Symbolizing the North and the Nile Delta, the red crown was worn by the serpent goddess Wadjet and the warrior goddess Neith.[6]

Nested one inside the other, the white and red crowns form the double crown pa-sekhemty, "the Two Mighty Ones", which the Greeks, by linguistic deformation, called pschent.[7] This double crown symbolized the union of the country, of which the Pharaoh was the guarantor. On a divine level, the pschent was worn by Atum, the creator god, by Mut, Amun's consort, and by the falcon Horus, protector of the double monarchy and archetypal model of the pharaoh.[8]

The origins of the white and red crowns are lost in the mists of prehistory, but both seem to have originated in Upper Egypt alone.[9] The earliest depiction of the red crown appears on pottery found at Naqada (Nubt) and dated to the Naqada I period (3800 / 3500 BC). The earliest depiction of the white crown is on a censer found at Qustul in Lower Nubia (circa 3150 BC), a locality linked to the Egyptian city of Nekhen from which the unifying will of Egypt originated. As a result, throughout Pharaonic history, the superiority of the white crown over the red one was an established fact. The oldest representation of the pschent -engraved on a rock in the western desert dates back to the reign of Djet (first dynasty). Subsequently, the same crown appears on an ivory label dated to the reign of Den and found at Abydos.[10] According to French Egyptologist Bernadette Menu, archaic documentation suggests that the two crowns, before being geographical markers, were indicators of the two main roles played by the pharaoh. Wearing the white crown, he repelled disorder by massacring his enemies with a mace in hand, while wearing the red crown, he brought prosperity by surveying the fields and taking a census of the herds.[11]

-

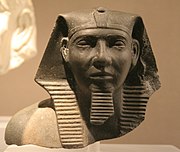

Senusret III wearing the white crown, Musée du Louvre.

-

Mentuhotep II wearing the red crown, Cairo Museum.

-

Senusret III crowned with the Pschent, Luxor Museum.

Headdresses

Although they were not crowns, some headdresses were reserved for the gods and the pharaoh. The nemes was a pleated, striped cloth in lapis lazuli blue and yellow.[12] Worn over the head, it completely enveloped the hair and fell to the chest and behind the shoulders, where it was gathered into a sort of braid. A snake-uraeus was positioned at forehead level, with its throat dilated, ready to strike down a potential assailant. When the Pharaoh didn't wear a nemes, he was sometimes content with a simple wig, inflated at the back, the khat, girded with the headband holding the uraeus.[13] The nemes seemed to be worn only in a cultic context, when the pharaoh was officiating before the gods, or in a funerary context.[14] The earliest attestation dates back to a statue of King Djoser (3rd Dynasty) placed in the serdab of the Step Pyramid (circa 2650 BC).[15] The most colossal representation of this headdress is that of the Giza sphinx, whose head represents a king of the 4th dynasty: Khufu or Khafre.[16] In the tomb of Tutankhamun (18th dynasty), rediscovered in 1922, the head of the royal mummy wore a finely-worked gold funerary mask. The pharaoh was shown wearing the nemes with the symbols of the goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet (vulture and ureus)[17] on his forehead. In royal statuary, numerous representations show the sovereign wearing the nemes headdress, which served as a support for the pschent double-crown.[18]

-

View of the Nemes's stern.

Nicknamed the "blue crown", the khepresh is a late headgear reserved exclusively for pharaohs. It appeared at the end of the Middle Kingdom, but only became common during the 18th and 19th dynasties, when the rulers were in battle.[19] The headdress is relatively tall, bulbous and studded with numerous small circular golden lozenges. For a long time, Egyptologists mistakenly considered this headdress to be an iron war helmet, as the ruler wore it quite frequently in battle scenes, during military parades or at certain religious celebrations such as the Min Festival. It is in fact a distinctive sign of the monarch, a mark of triumph, probably made of fabric or leather.[20]

Uraeus

The word uraeus is the Latinized form of a Greek term derived from iâret, the Egyptian name for the cobra, which also means "to ascend, to rise, to stand up".[21] This snake, ready to attack, is seen attached to the foreheads of gods, pharaohs and sometimes queens. As a pharaonic insignia, the uraeus is an ornament attached to crowns (white, red, pschent) and headdresses (nemes, khepresh).[22] The earliest depiction of the uraeus on a royal brow dates back to the reign of Den (1st Dynasty), on an ivory label showing the king stunning an enemy.[23] The cobra is one aspect of the Eye of Ra, which can also take the form of a woman (the word eye is feminine in Egyptian) or a dangerous lioness. The function of the Uraeus is clear. This female snake is a powerful symbol of protection, power and benevolence.[24] Attached to the pharaoh's forehead, the cobra spits venom fire at the kingdom's enemies. The reptile thus assumes both aggressive and apotropaic power in the face of the evil forces of chaos.[25] In the earliest royal scenes, the pharaoh was led by a courtier bearing a sign featuring the canine Wepwawet "The Way Opener", standing on all fours and accompanied by a protective uraeus.[26] The serpent appeared alone on the Pharaoh's forehead when he was alive. In death, the sovereign wore the cobra and the vulture's head, namely Wadjet and Nekhbet, the two protective goddesses of the Egyptian Double Country. This was the case on Tutankhamun's anthropomorphic sarcophagus, his Ushabtis and his canopic jars.[17] The foreheads of the Nubian pharaohs of the 25th dynasty featured two serpents, perhaps to symbolize their dual power, over the Nubia from which they came and over the Egypt they tried to conquer, without ever fully succeeding, in the Nile delta held by the 26th dynasty.[27]

Sceptres

The sceptre-heqa is surely the oldest symbol of Pharaonic domination. It represents a shepherd's crook, a stick with a curved end.[28] The hook and its spread were designed to grasp an ovis or caprinae (ewe, goat) by the hind leg in order to administer care. The symbolism of the Pharaonic crook is simple to analyze. Reflecting the pastoral aspects of Egyptian society, the Pharaoh was the shepherd of his people, guiding and protecting them.[29] In hieroglyphic writing, the image of the crozier served as an ideogram for the concept of "power/authority/sovereignty", noting the words "regional governor" and "foreign sovereign".[30] The two oldest known examples came from the royal necropolis of Abydos (Cemetery U). The first is fragmentary and dates from the end of the Naqada II period, while the second is complete and dates from the end of the Predynastic period. The latter was found in tomb U-j, where a Thinite ruler was buried, possibly King Scorpion. The earliest representation of a pharaoh with a Heqa scepter in his hand is a small statuette bearing the name of Ninetjer (2nd Dynasty).[29] On the other hand, the same figure holds the nekhekh flail (or flagellum). Often misrepresented as a fly swatter, the nekhekh was actually used to prod cattle. It, too, was a symbolic object born of the Egyptian agricultural mentality, which was strongly influenced by the values of animal husbandry.[31] With the development of the Osirian cult from the 4th Dynasty onwards, the scepter-heqa and flail-nekhekh became attributes of Osiris; the funerary god holding both in his two hands and crossed over his chest. By assimilation with this important divinity, pharaohs were also depicted in this posture, notably on the Osiride pillars of their monuments of eternity and on their sarcophagi.[32]

Bull tail

The animal world greatly influenced royal iconography during the formation of the Pharaonic state.[33] On several commemorative cosmetic palettes dating from the Predynastic Period, the Pharaoh was depicted in animal form. The idea was to show that the Egyptian ruler was imbued with the supernatural forces of nature. On the Battlefield Palette, Pharaoh appeared as a lion, while on the Bull Palette and Narmer Palette (verso, lower register), he appeared as a raging bull. He trampled on his vanquished enemies, depicted as a panicked, dismembered men. The lion and the bull were two animals that symbolized ferocity.[32] When the sovereign appropriated these appearances, it was a pictorial device that artists used to show his role as defender of Creation and fierce opponent of the forces of chaos. During the first two dynasties (or Thinite Period), royal iconography was codified. During this process, representations of the Pharaoh in entirely animal form were abandoned. References to the natural world were retained, however, but appeared in more subtle forms. The innate power of the bull, namely its virility and strength, was evoked by the bull's tail worn by the Pharaoh, suspended from the back of his loincloth. The earliest known depiction of the bull's tail appears on the Scorpion Macehead. From then on, the bull's tail became a canonical attribute of Pharaonic costume right up to the end of Egyptian royalty.[34]

Beard

The Pharaoh's face was usually shown hairless and clean-shaven. A rare white stone ostracon featured a drawing of a king with unshaven stubble. From the testimony of the Greek Herodotus, we learn that in Egypt, close relatives of the deceased grew beards and no longer cut their hair. This tells us that the new pharaoh was in mourning for his predecessor.[35] The ceremonial beard (or hairpiece) was, however, a royal insignia attested as early as the Predynastic period. Pharaohs shared this attribute with male deities, and it served to distinguish them from ordinary mortals. The beard took the form of a long braided artificial goatee, straight or curved at the tip, worn on the chin and attached to the ears by a long golden thread. The Pharaoh Hatshepsut (18th Dynasty), as holder of supreme power, didn't hesitate to wear this typically masculine attribute.[36]

Sandals

The sandals worn by the Pharaoh were also imbued with religious symbolism, as they constituted the point of contact between him and the territory over which he exercised his power. In the First Dynasty, the front and back of the Narmer Palette showed a courtier holding the sandals while the king went about his rituals barefoot. Later, the sandal-bearer took on an important administrative role, due to his close relationship with his master. In official discourse and imagery, the symbolic role of royal sandals was linked to the myth of the struggle between order and chaos. The Pharaoh's primary role was to crush Egypt's enemies, represented by the inhabitants of neighboring lands (Nubians, Libyans, Asians). To deflect evil influences, bound enemies were depicted on the stool in front of the throne or on the pavement of the processional roadways. Each time the sovereign stepped on these representations, Pharaonic victory was symbolically consummated. In each case, the agents of victory were the sandals, with the country's enemies placed beneath them.[26]

Yes! we ensure his physical protection by warding off the Nine Bows, since you chose him out of millions to do what pleases our Ka. And so we give him the duration of Ra and the years of Atum, with all the lands under his sandals, forever - yes, forever!

Case-mekes

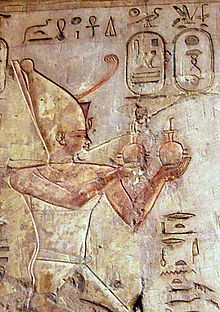

The oldest documentation refers to the mekes as a kind of scepter with the appearance of a mace-stick. The object is mentioned in this form in the Pyramid Texts engraved in the tombs of Pharaohs Unas and Pepi I. Later, during the New Kingdom, it became a small scroll, a kind of case, which the king held firmly in one of his hands.[38] In statuary from the 19th Dynasty onwards, Ramesses II was commonly depicted with this attribute. According to the terms of the royal speech, the case-mekes was supposed to contain a divine decree drawn up by Thoth. This document declared the Pharaoh, like Osiris and Horus, the heir of Geb, the god of the earth. The transmission of this earthly heritage was often also the work of the Theban god Amun. The decree was known as an imit-per and was presented as a deed of ownership or a kind of inventory describing the possessions of the royal domain.[39][40]

I place my temple under your responsibility, O venerable father. I have drawn up a written statement of its assets for you to have in hand: I have set up an "imit-pert" for you from all the lists in my possession, so that they may be forever established in your name. For I administer the Two Lands for you, in accordance with the inheritance you bestowed on me at my birth.

References

- ^ Vernus & Yoyotte 1998, p. 124.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 186, §.1.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 186, §.2.

- ^ Franco 1999, pp. 61, 64.

- ^ a b Franco 1999, p. 63.

- ^ a b Franco 1999, p. 64.

- ^ Vernus & Yoyotte 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Franco 1999, pp. 61–64, 205.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 192.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 192–196.

- ^ Menu 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Franco 1999, p. 177.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Leclant 2011, pp. 588–589.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Leclant 2011, pp. 2051–2052.

- ^ a b Desroches Noblecourt 1988, passim.

- ^ Corteggiani 2007, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Franco 1999, p. 141.

- ^ Damiano-Appia 1999, p. 152.

- ^ Corteggiani 2007, p. 563.

- ^ Franco 1999, p. 257.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Franco 1999, p. 257-258.

- ^ Leclant 2011, p. 2239.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Corteggiani 2007, pp. 563–564.

- ^ Franco 1999, p. 224.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 1999, p. 189.

- ^ Bonnamy & Sadek 2010, p. 437.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 190.

- ^ a b Obsomer 2012, photographies 10a. 11a. 11c. 15c.

- ^ Huet & Huet 2013, pp. 13–21.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Vercoutter 2007, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Bonhême & Forgeau 1988, pp. 30, 32–33.

- ^ Grimal 1986, p. 501.

- ^ Franco 1999, p. 161.

- ^ Menu 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Grimal 1986, pp. 640–641.

- ^ Grimal 1986, p. 641.

Bibliography

- Bonhême, Marie-Ange; Forgeau, Annie (1988). Pharaon : Les secrets du Pouvoir (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 978-2-200-37120-3.

- Bonnamy, Yvonne; Sadek, Ashraf (2010). Dictionnaire des hiéroglyphes : hiéroglyphes-français (in French). Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-7427-8922-1. BnF 42204095k

- Corteggiani, Jean-Pierre (2007). L'Égypte ancienne et ses dieux, dictionnaire illustré (in French). Illustrated by Laïla Ménassa. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-62739-7.

- Damiano-Appia, Maurizio (1999). L'Égypte. Dictionnaire encyclopédique de l'Ancienne Égypte et des civilisations nubiennes (in French). Paris: Gründ. ISBN 978-2-7000-2143-1.

- Desroches Noblecourt, Christiane (1988) [1963]. Toutânkhamon, vie et mort d'un pharaon (in French). Paris: Pygmalion. ISBN 978-2-85704-012-5.

- Franco, Isabelle (1999). Nouveau dictionnaire de mythologie égyptienne (in French). Paris: Pygmalion. ISBN 978-2-85704-583-0.

- Grimal, Nicolas-Christophe (1986). Les termes de la propagande royale égyptienne de la XIXe dynastie à la conquête d'Alexandre (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale / Diffusion de Boccard. ISSN 0398-3595.

- Huet, Philippe; Huet, Marie (2013). L'animal dans l'Égypte ancienne (in French). Saint-Claude-de-Diray: Éditions Hesse. ISBN 978-2-35706-026-5.

- Leclant, Jean, ed. (2011) [2005]. Dictionnaire de l'Antiquité (in French). Paris: PUF. ISBN 978-2-13-058985-3.

- Menu, Bernadette (2004). Égypte pharaonique : Nouvelles recherches sur l'histoire juridique, économique et sociale de l'ancienne Égypte (in French). Preface by Charles de Lespinay and Raymond Verdier. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7475-7706-9.

- Obsomer, Claude (2012). Ramsès II (in French). Paris: Pygmalion. ISBN 978-2-7564-0588-9.

- Vercoutter, Jean (2007). À la recherche de l’Égypte oubliée. Découvertes Gallimard / Archéologie (no 1) (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-034246-4.

- Vernus, Pascal; Yoyotte, Jean (1998) [1988]. Dictionnaire des pharaons (in French). Paris: Éditions Noêsis. ISBN 978-2-7028-2001-8.

- Wilkinson, Toby A.H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-18633-9.