Northern Liang

Northern Liang (北涼) 建康 (397–399), 涼 (399–401, 431–433), 張掖 (401–412), 河西 (412–431, 433–441, 442–460), 酒泉 (441–442) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

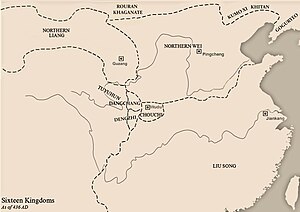

Northern Liang and other Asian polities in 400 AD | |||||||||||||||

Northern Liang at its greatest extent in 436 AD | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of Later Qin, Eastern Jin, Northern Wei, Liu Song | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Jiankang (397–398) Zhangye (398–412) Guzang (412–439) Jiuquan (440–441) Dunhuang (441–442) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital-in-exile | Shanshan (442) Gaochang (442–460) | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||||||||

• 397–401 | Duan Ye | ||||||||||||||

• 401–433 | Juqu Mengxun | ||||||||||||||

• 433–439 | Juqu Mujian | ||||||||||||||

• 442–444 | Juqu Wuhui | ||||||||||||||

• 444–460 | Juqu Anzhou | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Mongolia | ||||||||||||||

The Northern Liang (Chinese: 北涼; pinyin: Běi Liáng; 397–439) was a dynastic state of China and one of the Sixteen Kingdoms in Chinese history. It was ruled by the Juqu (沮渠) family of Lushuihu (盧水胡) origin, a branch of the Xiongnu.[3] Although Duan Ye of Han ethnicity was initially enthroned as the Northern Liang ruler with support from the Juqu clan, Duan was subsequently overthrown in 401 and Juqu Mengxun was proclaimed monarch.

All rulers of the Northern Liang proclaimed themselves "wang" (translatable as either "prince" or "king").

History

Background

For most of its existence, the Northern Liang dynasty was ruled by the Juqu tribe of Lushuihu ethnicity. The Lushuihu, or "Lu River Barbarians", were a complex ethnic group believed to be a mix of the Xiongnu, Yuezhi, Qiang and other people that lived along the Lu River in present-day Zhangye, Gansu. The Juqu in particular descended from or were heavily influenced by the Xiongnu, as they derived their family name from a Xiongnu office that their ancestors once held.

The Juqu found themselves serving under the Di-led Later Liang dynasty. After Liang suffered a heavy defeat to the Western Qin in 397, two members, Juqu Luochou (沮渠羅仇) and Juqu Quzhou (沮渠麴粥) were blamed for the loss and executed. At their funeral, their nephew, Juqu Mengxun riled up the ten thousands in attendant to rebel and avenge their kin. He was defeated early on, but his cousin, Juqu Nancheng, rallied his troops and convinced Duan Ye, the Administrator of Jiankang (建康, in modern Zhangye, Gansu) and a Han Chinese, to lead their rebellion.

Reign of Duan Ye

Duan Ye took the imperial title of Duke of Jiankang and changed the era name, although real power was shared between him, Juqu Mengxun and Juqu Nancheng. In 398, Mengxun took several commanderies before capturing Zhangye, effectively controlling the western parts of Later Liang. Duan Ye shifted the capital to Zhangye, and in 399, he elevated himself to King of Liang. To distinguish with the other Liang states at the time, historiographers refer to his state as Northern Liang.

However, in 400, the Administrator of Dunhuang, Li Gao rebelled in his commandery and established the Western Liang, taking over the westernmost region and attracting the local Han Chinese. Tension also arose between Mengxun, Nancheng and Duan Ye. In 401, Mengxun manoeuvred into killing Nancheng and Duan Ye, seizing power for himself.

Reign of Juqu Mengxun

Juqu Mengxun claimed the title of Duke of Zhangye. With the Western Liang breaking away, the Northern Liang was weaker than it was before and had to rely on careful diplomacy with their neighbours. Initially, Mengxun allied with the Southern Liang to destroy Later Liang, achieving so in 403. He then declared himself a vassal of the Later Qin and began clashing with Southern Liang and Western Liang. He repelled several attacks by Southern Liang, and in 410, even besieged their capital Guzang (姑臧, in modern Wuwei, Gansu) but without success. The inhabitants of Guzang later surrendered to him in 411, and in 412, he made the city his new capital, where he elevated himself to the King of Hexi.

Northern Liang continued to place pressure on Southern Liang before they fell to Western Qin in 414. Their demise placed Northern Liang in contact with Qin, sparking a new conflict between them. In 417, taking advantage of Li Gao's death, he went on the offensive against Western Liang. By 421, he captured their capital, Jiuquan and destroyed their last pocket of resistance in Dunhuang, ending the Western Liang. Thus, the Northern Liang became the sole power in the Hexi Corridor and began trading with the Western Regions.

With their western frontier secured, Northern Liang now concentrated their resources on the Western Qin. They allied themselves with the Helian Xia in the Guanzhong and launched a series of attacks on Qin, gradually weakening them. Previously, Northern Liang had submitted to the Eastern Jin in the south vassal, and they continued to send tribute to their successor, the Liu Song, who affirmed Mengxun's imperial title in 423. However, in 431, both Western Qin and Xia fell, and Nothern Liang was now in direct contact with the powerful Northern Wei dynasty. As a result, Mengxun decided to become a vassal to Wei, who bestowed him the title of King of Liang.

Reign of Juqu Mujian

Juqu Mengxun grew deathly ill in 433, and as he was dying, his officials considered his heir apparent, Juqu Puti (沮渠菩提) as being too young to lead and supported another son, Juqu Mujian to the throne. At this point, the Northern Wei was on the verge of unifying northern China. After succeeding his father, Mujian was compelled into entering a marriage alliance with Wei, sending his sister Princess Xingping to marry Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei while he married Taiwu's sister, Princess Wuwei, and Wei granted him the title of King of Hexi. Meanwhile, he was also a vassal to the Liu Song, who he engaged with in cultural exchange by trading literature works from their respective territories.

Despite their alliance, Emperor Taiwu was determined to complete his unification. In 439, alleging that Mujian was planning to rebel, the Northern Wei launched a campaign against Northern Liang and placed Guzang under siege. Mujian surrendered himself to Wei, thus ending the Northern Liang. The Northern Liang was the last of the so-called Sixteen Kingdoms, and their fall in 439 marked a formal end to the period.

Northern Liang of Gaochang (442-460)

Juqu Mujian was initially treated with respect in Wei, but in 447, he was again accused of plotting to rebel and executed. While he was in Wei, his brothers, Juqu Wuhui and Juqu Anzhou, tried to revive their state in their former territory, but eventually settled for the oasis city of Gaochang in 442. In historiography, their state is known as the "Northern Liang of Gaochang" (Chinese: 高昌北涼; pinyin: Gāochāng Běi Liáng; 442–460). In 444, Juqu Wuhui submitted to the Liu Song and received the title of King of Hexi. He died shortly after and was succeeded by Juqu Anzhou. Anzhou destroyed the Jushi Kingdom in 450 and attempted to maintain friendly relations with the Rouran Khaganate. However, in 460, the Rouran conquered Gaochang and slaughtered the remnants of the Juqu family.[4]

Buddhist cave sites and art

The Juqu were strong propagators of Buddhism, and it was during the Northern Liang that the first Buddhist cave shrine sites appear in Gansu Province.[5] The two most famous cave sites are Tiantishan ("Celestial Ladder Mountain"), which was south of the Northern Liang capital at Yongcheng, and Wenshushan ("Manjusri's Mountain"), halfway between Yongcheng and Dunhuang. Maijishan lies more or less on a main route connecting China proper and Central Asia (approximately 150 miles (240 km) west of modern Xi'an), just south of the Weihe (Wei River). It had the additional advantage of located not too distant from a main route that also ran N-S to Chengdu and the Indian subcontinent. The Northern Liang also built and decorated the first decorated Mogao Caves (caves 268, 272 and 275) from 419 to 439 CE until the Northern Wei invasion.[6][7] They have many common points and were built at the same time as Cave 17 of the Kizil Caves.[8][9]

-

Figure of Maitreya Buddha in cave 275 from Northern Liang

-

Devas. Dunhuang mural. Cave 272, Northern Liang dynasty

-

King Bhilanjili Jataka. Mogao cave 275. Northern Liang.

-

Epitaph of Juqu Fengdai (沮渠封戴, ?—455), Prefect of Gaochang (高昌太守) under the Northern Liang of Gaochang. Excavated in 1972 in the Astana Cemetery

Rulers of the Northern Liang

| Temple name | Posthumous name | Personal name | Durations of reign | Era names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Liang (397–439) | ||||

| – | Duan Ye | 397–401 | Shenxi (神璽) 397–399 Tianxi (天璽) 399–401 | |

| Taizu | Wuxuan | Juqu Mengxun | 401–433 | Yongan (永安) 401–412 Xuanshi (玄始) 412–428 |

| – | Ai | Juqu Mujian | 433–439 | Yonghe (永和) 433–439 |

| Northern Liang of Gaochang (442–460) | ||||

| – | Juqu Wuhui | 442–444 | Chengping (承平) 443–444 | |

| – | Juqu Anzhou | 444–460 | Chengping (承平) 444–460 | |

Rulers family tree

| Northern Liang rulers family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Prince of Hexi

- Xiongnu

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- Five Barbarians

- Sixteen Kingdoms

- Gansu

- Gaochang

References

- ^ "中央研究院網站".

- ^ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 123.

- ^ Xiong, Victor (2017). Historical Dictionary of Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 315. ISBN 9781442276161.

- ^ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

kao-ch'ang northern liang family turfan kingdom.

- ^ Michael Sullivan, The Cave-Temples of Maichishan. London: Faber and Faber, 1969.

- ^ Bell, Alexander Peter (2000). Didactic Narration: Jataka Iconography in Dunhuang with a Catalogue of Jataka Representations in China. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-8258-5134-7.

- ^ Whitfield, Roderick; Whitfield, Susan; Agnew, Neville (15 September 2015). Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art History on the Silk Road: Second Edition. Getty Publications. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-60606-445-0.

- ^ Bell, Alexander Peter (2000). Didactic Narration: Jataka Iconography in Dunhuang with a Catalogue of Jataka Representations in China. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-8258-5134-7.

- ^ Whitfield, Roderick; Whitfield, Susan; Agnew, Neville (15 September 2015). Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art History on the Silk Road: Second Edition. Getty Publications. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-60606-445-0.