Medium-density housing

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Medium-density housing is a term used within urban planning and academic literature to refer to a category of residential development that falls between detached suburban housing and large multi-story buildings. There is no singular definition of medium-density housing as its precise definition tends to vary between jurisdiction. Scholars however, have found that medium density housing ranges from about 25 to 80 dwellings per hectare, although most commonly sits around 30 and 40 dwellings/hectare.[1][2][3] Typical examples of medium-density housing include duplexes, triplexes, townhouses, row homes, detached homes with garden suites, and walk-up apartment buildings.[2][3]

In Australia the density of standard suburban residential areas has traditionally been between 8-15 dwellings per hectare.[1] In New Zealand medium-density development is defined as four or more units with an average density of less than 350m2.[4] Such developments typically consist of semi-attached and multi-unit housing (also known as grouped housing) and low-rise apartments.

In the United States, medium-density housing is usually referred to as middle-sized or cluster development that fits between neighborhoods with single family homes and high-rise apartments. This kind of development is usually intended to bridge the gap between low- and high-density neighborhoods. Because this kind of housing refers to density specifically, the type of building or number of units can vary. Medium-density housing in America has historically been perceived as undesirable due to the affordable nature of the housing that attracts low-income residents, and its perceived breach on the established suburban lifestyle.[5] The various styles of medium-density housing are now being considered as more sustainable development options to help solve the housing crisis in America.[6]

Characteristics

Medium-density housing is commonly identified by how it contrasts both suburban development and high-density development. Suburbs are characterized by large lot sizes, generous setbacks from the street, low density, and single-uses.[7] High-density development, such as high-rise apartment towers have very high density with minimal setbacks and located near a variety of other land uses and transit connections.[2][3] In contrast, medium-density development sits between these two extremes. Buildings usual are no taller than 4 stories, shorter than high-rises, but with smaller setbacks and individual lots than suburban areas. [3][8]

Most often, medium-density housing provides multiple housing units within a shared structure. These buildings tend to share common infrastructure such as party walls, water mains, parking areas, and green space.[3] Due to the sharing of infrastructure and co-location of multiple units in a single building, medium-density housing tends to have lower per unit construction costs than single-family homes. [3] Lower construction cost result in lower housing prices, mean that medium-density housing is often more affordable than a detached home. Many have suggested that increasing the supply of medium-density housing, known as the Missing Middle, is crucial to improving housing affordability in North America.[9]

Medium-density housing allows for more compact development meaning distances between destinations is shortened.[8] As a result, areas of medium-density are more likely to be mixed-use with easy access to shopping and services.[8]

- Close proximity to community services and amenities

- Efficient use of land, resources, and infrastructure

- Small to medium footprints

- Smaller, well-designed units

- Simple construction

- Reduced parking

- A sense of community

- More affordable

History

United States

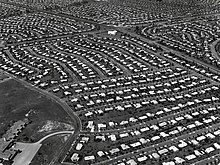

In the U.S. most medium-density or middle-sized housing was built between the 1870s and 1940s[10] due to the need to provide denser housing near jobs. Examples include the streetcar suburbs of Boston which included more two-family and triple-decker homes than single-family homes,[10] or areas like Brooklyn, Baltimore, Washington D.C. or Philadelphia[10] which feature an abundance of row-houses. This type of housing, once an affordable option for rental or homeownership has turned into luxury development due to the rising land and construction costs of nearby developments.[11] Before WW1 the Garden-city movement had become an increasingly popular method for planning neighborhoods. As the U.S. began experiencing a housing crisis for war workers, it began a mass production of housing that followed the Garden-city form. This greatly impacted development patterns across the United States until the Great Depression. During the Great Depression the U.S. government passed the National Housing Act of 1934 to create the Federal Housing Authority with the goal of providing more federally backed loans to Americans so they could purchase homes. This led to the White Flight of the 1940s because many White Americans were able to move from urban cities to homes at the outskirts of the city, as well as purchase cars. This furthered the suburbanization of America which led to the increase in home sizes, land use, automobile use and contributed to suburban sprawl.[12] Neighborhoods were no longer built to human scale, but rather built to accommodate larger developments; in the suburbs this meant larger single family homes and wider roads for cars and in the city high-rise apartments.[12]

In the 1960s architects identified a stark difference between neighborhoods created by high-rise development and suburban sprawl, and realized there was a need for more medium-density or middle-sized housing to bridge the gap between cities and suburbs.[5] Architects and developers started building cluster housing to address this gap in housing but these kinds of developments weren't marketed towards low-income residents in need of housing.[5] Due to the recession in the 70's President Nixon issued a moratorium on government funding for low-income housing.[5] Medium-density or cluster development were framed as an undesirable but necessary solution to the housing crisis by TV programs and newspapers.[5] Established suburbs of the postwar-era had created distinctions between home and work life, also distancing themselves from their neighbors.[5] The introduction of medium-density housing into established suburbs was not allowed due to exclusionary single-family zoning and because it was viewed breach of family fundamentals that had been established with suburban living.[5] Medium-density, cluster or middle-sized housing was referred to as an inadequate, makeshift substitute for those who couldn't afford suburban living.[5] This perception of medium-density or middle sized housing has been thought to be fueled by irrational fears of density[12] and wanting to keep low-income residents out of suburban neighborhoods.[5] This led to the decrease of medium or middle-sized housing in America, referred to as Missing Middle Housing.

Australia

Many traditional types of housing developed prior to car-based cities were at comparable densities, such as the terraced (row) or courtyard housing found in many parts of the world. The inner suburbs in many Australian cities and those activity centres developed during the late Victorian suburban boom have examples of medium density housing. Since the 1960s, many Australian states have encouraged urban consolidation policies which have facilitated the construction of medium density housing. The debate around medium-density housing arose during the Garden Suburbs movement. The first studies on medium-density housing happened during the 1960s during the post-war housing boom, focusing on housing consumption rather than sustainability and affordability.[13] In the 1970s more studies performed investigated barriers to producing medium-density housing and attributed them to planning. Studies in the 1980s and 1990s however focused more on perceptions of medium-density housing and how it is designed.[13] Despite positive perceptions of medium-density housing from those who actually lived in it, people living in less dense housing perceived it as negative.[13]

New Zealand

In New Zealand housing has historically focused on a semi-rural or suburban density and has experienced extensive suburban sprawl.[14] Several reports have highlighted the need for medium-density housing in New Zealand as a means of providing affordable sustainable housing.[15]

Criticism

The design of medium density housing requires careful consideration of urban design principles. In some cases, urban consolidation policies have allowed demolition of existing low-density housing across established residential suburbs, replacing them with various forms of medium-density dwellings. Because of this, many medium-density developments have been controversial in the last 20–30 years because of their perceived negative impacts on the neighborhood character of established residential areas.

In Australia there has been an increasing policy emphasis by state and local governments to regulate the design of new medium density developments, such as the Victorian government's ResCode, released in 2001, and the metropolitan strategy, Melbourne 2030, which seeks to confine such housing to activity centers.

In America, restrictive zoning and "no-growth" ordinances stop cities and towns from densifying their neighborhoods with medium-density or middle-sized housing. Rezoning a city or town can be time-consuming, costly and remains susceptible to community pushback by NIMBYs. Critics of goldilocks density, a term coined by Lloyd Alter, argue that medium-density housing is not a blanket solution for the housing crisis different cities face because each cities will need to take a different approach.[16]

See also

- Urban density

- Missing middle housing

- Green building

- Affordable housing

- Save Our Suburbs

- Transit oriented development

- New Urbanism

- Subsidized housing in the United States

- Urban sprawl

- Not In My Backyard movement

- Exclusionary zoning

References

- ^ a b "The Low Rise Housing Diversity Code". www.planning.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ a b c Hodge, Gerald; Gordon, David; Shaw, Pamela (2021). Planning Canadian communities: An introduction to the principles, practices, and participants in the 21st century. Toronto: Nelson. ISBN 978-0-17-670549-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Ellis, John (2004). "Explaining residential densities" (PDF). Places. 16 (2): 34–43.

- ^ "Medium-density housing in New Zealand | Ministry for the Environment". www.mfe.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wright, Gwendolyn (1988). Building the Dream. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 313–329.

- ^ "New Report Shows America's Rental Affordability Crisis Climbing the Income Ladder | Joint Center for Housing Studies". www.jchs.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ^ Song, Yan; Knapp, Gerrit-Jan (2004). "Measuring urban form: Is Portland winning the war on sprawl?". Journal of the American Planning Association. 70 (2): 210–225. doi:10.1080/01944360408976371. S2CID 154330919.

- ^ a b c Yang, Yizhao (2008-07-30). "A Tale of Two Cities: Physical Form and Neighborhood Satisfaction in Metropolitan Portland and Charlotte". Journal of the American Planning Association. 74 (3): 307–323. doi:10.1080/01944360802215546. ISSN 0194-4363. S2CID 153450307.

- ^ Wegmann, Jake (2020-01-02). "Death to Single-Family Zoning…and New Life to the Missing Middle". Journal of the American Planning Association. 86 (1): 113–119. doi:10.1080/01944363.2019.1651217. ISSN 0194-4363. S2CID 213724059.

- ^ a b c "Will U.S. Cities Design Their Way Out of the Affordable Housing Crisis?". nextcity.org. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ "Greater Boston Housing Report Card: Housing Equity and Resilience in Greater Boston's Post-COVID Economy". www.tbf.org. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ a b c Friedman, Avi; Krawitz, David (2001). Peeking Through the Keyhole: The Evolution of North American Homes. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b c King, Anthony (1999). Medium-Density Housing under the Good Design Guide A Study of the Experiences of Residents and Neighbours. Melbourne: Housing Industry Association Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- ^ Marriage, Guy; Blenkarne, Eliot (2015). "Density comparisons in New Zealand and European housing" (PDF). The Architectural Science Association and the University of Melbourne: 247–256.

- ^ "Embracing higher density housing is a positive sign that Auckland is growing up". Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ "Is There a Perfect Density?". Planetizen - Urban Planning News, Jobs, and Education. Retrieved 2020-12-17.