Life unworthy of life

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

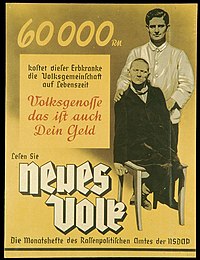

The phrase "life unworthy of life" (German: Lebensunwertes Leben) was a Nazi designation for the segments of the populace which, according to the Nazi regime, had no right to live. Those individuals were targeted to be murdered by the state ("euthanized"), usually through the compulsion or deception of their caretakers. The term included people with serious medical problems and those considered grossly inferior according to the racial policy of Nazi Germany. This concept formed an important component of the ideology of Nazism and eventually helped lead to the Holocaust.[1] It is similar to but more restrictive than the concept of Untermensch, subhumans, as not all "subhumans" were considered unworthy of life (Slavs, for instance, were deemed useful for slave labor.).

The "euthanasia" program was officially adopted in 1939 and came through the personal decision of Adolf Hitler. It grew in extent and scope from Aktion T4 (which ended officially in 1941 when public protests stopped the program), through the Aktion 14f13 against concentration camp inmates.[2] The "euthanasia" of certain cultural and religious groups and those with physical and mental disabilities continued more discreetly until the end of World War II. The methods used initially at German hospitals such as lethal injections and bottled gas poisoning were expanded to form the basis for the creation of extermination camps where cyanide gas chambers were purpose-built to facilitate the extermination of the Jews, Romani, communists, anarchists, and political dissidents.[3]: 31 [4][5]

Historians estimate that 200,000 to 300,000 people were murdered under this program in Germany and occupied Europe.[6][7][8][a]

History

The expression first appeared in print via the title of a 1920 book, Die Freigabe der Vernichtung Lebensunwerten Lebens (Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life) by two professors, the jurist Karl Binding (retired from the University of Leipzig) and psychiatrist Alfred Hoche from the University of Freiburg.[9] According to Hoche, some living people who were brain damaged, intellectually disabled and psychiatrically ill were "mentally dead", "human ballast" and "empty shells of human beings". Hoche believed that killing such people was useful. Some people were simply considered disposable.[10] Later the killing was extended to people considered 'racially impure' or 'racially inferior' according to Nazi thinking.[11]

The concept culminated in Nazi extermination camps, instituted to systematically murder those who were unworthy to live according to Nazi ideologists. It also justified various human experimentation and eugenics programs, as well as Nazi racial policies.

Development of the concept

According to the author of Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, the policy went through a number of iterations and modifications:

Of the five identifiable steps by which the Nazis carried out the principle of "life unworthy of life," coercive sterilization was the first. There followed the killing of "impaired" children in hospitals; and then the killing of "impaired" adults, mostly collected from mental hospitals, in centers especially equipped with carbon monoxide gas. This project was extended (in the same killing centers) to "impaired" inmates of concentration and extermination camps and, finally, to mass killings in the extermination camps themselves.[1][11]

See also

- Aktion T4

- Nazi concentration camp badges

- Holocaust victims

- Department of Film (Nazi Germany)

- Glossary of Nazi Germany: Useless eaters

- Nazi eugenics

- Nazism and race

- Sagamihara stabbings

- Social cleansing

- Am Spiegelgrund clinic

References

- ^ a b Lifton, Robert Jay (23 July 2005). "The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide". holocaust-history.org. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Ley, Astrid (2021). "Euthanasie" und Holocaust. Brill Schöningh. pp. 195–210. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Crowe, David; Kolsti, John; Hancock, Ian (31 March 1992). The Gypsies of Eastern Europe (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0873326711. LCCN 90046710. OCLC 1031485541. OL 1885658M. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Henry Friedlander (1995), The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. University of North Carolina Press. September 1997. p. 163. ISBN 9780807846759.

- ^ Evans, Suzanne E. (January 2004). Forgotten crimes: the Holocaust and people with disabilities. p. 93. ISBN 1566635659.

- ^ "Exhibition catalogue in German and English" (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Memorial for the Victims of National Socialist ›Euthanasia‹ Killings. 2018.

- ^ "Euthanasia Program" (PDF). Yad Vashem. 2018.

- ^ a b Chase, Jefferson (26 January 2017). "Remembering the 'forgotten victims' of Nazi 'euthanasia' murders". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Cover of Die Freigabe der Vernichtung Lebensunwerten Lebens (Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life) at German Wikipedia.

- ^ Dr S D Stein, "Life Unworthy of Life" and other Medical Killing Programmes. UWE Faculty of Humanities, Languages, and Social Science – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Lifton, Robert Jay (21 September 1986). "German Doctors and the Final Solution". The New York Times. p. 64. eISSN 1553-8095. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

Notes

- ^ As many as 100,000 people may have been killed directly as part of Aktion T-4. Mass euthanasia killings were also carried out in the Eastern European countries and territories Nazi Germany conquered during the war. Categories are fluid and no definitive figure can be assigned but historians put the total number of victims at around 300,000.[8]

External links

- "Life Unworthy of Life" and other Medical Killing Programmes by Dr. Stuart D. Stein, University of the West of England

- Contemporary English translation of "Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of life" by Dr. Cristina Modak

- German text online of Die Freigabe der Vernichtung Lebensunwerten Lebens