J. Franklin Bell

James Franklin Bell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 9, 1856 Shelbyville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | January 8, 1919 (aged 62) New York City, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1878–1919 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands | Department of the East 77th Division Department of the West 4th Division Philippine Department Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army Colleges and Schools, Fort Leavenworth 3rd Brigade, Luzon Department 1st District, Luzon Department 4th Brigade, 2nd Division 36th U.S. Volunteer Infantry |

| Battles/wars | Indian Wars Spanish–American War Philippine–American War World War I |

| Awards | Medal of Honor Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal |

| Signature | |

James Franklin Bell (January 9, 1856 – January 8, 1919) was an officer in the United States Army who served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1906 to 1910.

Bell was a major general in the Regular United States Army, commanding the Department of the East, with headquarters at Governors Island, New York at the time of his death in 1919. He entered West Point in 1874, and graduated 38th in a class of 43 in 1878, with a commission as second lieutenant of the 9th Cavalry Regiment, a black unit.

Bell became notorious for his actions in the Philippine–American War, in which he ordered the detainment of Filipino civilians in the provinces of Batangas and Laguna into concentration camps, resulting in the deaths of over 11,000 people.[1]

Early life and education

Bell was born to John Wilson and Sarah Margaret Venable (Allen) Bell in Shelbyville, Kentucky. His mother died when he was young.[2] During the American Civil War, Bell's family, living in a border state, stood strongly in favor of the Confederacy.

In 1874, after two years of working in a general store,[3] Bell sought a military career, and secured appointment to West Point, where he eventually graduated 38th in a class of 43. The War Department assigned him to the 9th Cavalry, one of the black units formed after the Civil War. Then in Kentucky on home leave, Bell attempted to resign his commission. This, in fact, was illegal, but someone at the War Department understood the attitudes that were behind this action and assigned him to the all-white 7th Cavalry. He joined the unit at Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, on October 1, 1878.[4]

Indian Wars

Bell became an instructor of military science and tactics and taught mathematics at Southern Illinois University, a position held from 1886 until 1889. While in Illinois, he read law and passed the Illinois bar. In 1889, he returned to the 7th Cavalry. Although the regiment participated in the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota, Bell was on personal leave and did not participate. He was promoted to first lieutenant on December 29, 1890, and participated in the Pine Ridge, South Dakota campaign in 1891. Later that year, the 7th Cavalry was posted to Fort Riley, Kansas, and Bell joined the staff of the Cavalry and Light Artillery School. He soon became adjutant, then secretary of the school. In November 1894, Bell became aide-de-camp to General James W. Forsyth and posted to the Department of California. He was transferred to Fort Apache, Arizona Territory, in July 1897 and then to Vancouver Barracks, Washington, in February 1898.

Philippines

At the outbreak of the Spanish–American War, Bell was a first lieutenant acting as adjutant to General Forsyth, then commanding the Department of the West, with headquarters at San Francisco. He was commissioned as a major of volunteers in May 1898 and sent to the Philippines, where he participated in the attack on the Spanish forces in Manila from August 1 to 13.[5] In 1925, Bell was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for having conducted detailed reconnaissance of Fort San Antonio Abad on August 10, 1898.[6] This delayed award had originally been proposed as a Medal of Honor by General Wesley Merritt.[7]

After the end of hostilities with Spain, Bell was authorized to organize a regiment of volunteers. He was promoted to captain in the Regular Army in March 1899 and colonel of volunteers in July 1899. The 36th U.S. Volunteer Infantry was ordered to the Philippines and, under his command, saw service in the Philippine–American War.[5]

Bell was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions of September 9, 1899 near Porac on Luzon Island in the Philippines. According to the official citation, "while in advance of his regiment [Bell] charged 7 insurgents with his pistol and compelled the surrender of the captain and 2 privates under a close fire from the remaining insurgents concealed in a bamboo thicket."[8]

After a few months in the Philippines, Bell was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers in December 1899, outranking many officers previously his senior.[5] After commanding the 4th Brigade, 2nd Division from January to July 1900 and serving as Provost Marshal-General of Manila from July 1900 to February 1901, he received a direct promotion from captain to brigadier general in the Regular Army.[9]

Concentration camp policy

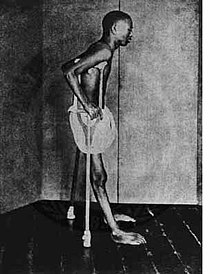

In late 1901, Bell was made commander of U.S. forces in the provinces of Batangas and Laguna by Philippine Governor-General William Howard Taft. In response to guerrilla attacks by general Miguel Malvar, Bell implemented counterinsurgency tactics, destroying crops and slaughtering livestock in order to starve insurgents into submission. Bell ordered all civilians in the area to relocate to internment camps, stating, "all able-bodied men will be killed or captured... old men, women and children will be sent to [concentration camps]".[10] Living conditions in the camps were poor, with inadequate sanitation leading civilians to fall ill with a multitude of diseases, including cholera, smallpox, beriberi, and bubonic plague.[11] One of Bell's subordinate officers described the camps as "some suburb of hell".[12] In response to disease outbreaks in the camps, Bell ordered a mass public vaccination campaign in Batangas.[13] Bell also forced all civilians to co-operate with occupying U.S. forces, stating that, "Neutrality should not be tolerated", and anyone accused of being part of the insurgency could be executed.[14]

Between January and April 1902, 8,350 people died in the camps out of a population of 298,000. Some camps experienced mortality rates as high as 20 percent. According to American historian Andrea Pitzer, Bell's reconcentration policy was "directly responsible" for over 11,000 deaths.[1] Some have claimed that Bell's tactics constituted war crimes, and accused Bell of waging a war of extermination.[15] Bell's tactics mirrored similar civilian reconcentration policies previously carried out by the Spanish in Cuba and by the British in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

According to a legal brief written for the United States Senate Committee on the Philippines in 1902 by Julian Codman and Moorfield Storey of the American Anti-Imperialist League, Bell said in an interview with The New York Times on May 3, 1901, that one-sixth of the population of Luzon had been killed or died of dengue fever in the previous two years of war. This would be 616,000 deaths according to Codman and Storey.[16] However, according to Gore Vidal in a 1981 article for The New York Review, his researchers found no reference to Bell in The New York Times on that date.[17] Luzon's population rose from 3,666,822 in 1901 to 3,798,507 in the 1903 census.[18]

Service in America and World War I

In July 1903, Bell was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he headed the Command and General Staff School until April 14, 1906; Bell was promoted major general, and was appointed Chief of the Army General Staff. He served for four years, under Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. Bell was the first chief officer of the United States Army in 45 years who had not served in the American Civil War.

When the United States military forces of the Western Pacific concentrated in the Philippines, he returned to Manila on January 1, 1911, as military commander, until war with Mexico seemed imminent in April 1914.[19] He was then ordered home to take command of the 4th Division. The 4th Division remained in Texas City as reserve and, although at several times he seemed about to cross the Rio Grande, he was never a part of the Mexican expeditionary force.

After the Mexican situation quieted, Bell was relieved of the 4th Division, and placed in command of the Department of the West in December 1915. He remained in command at San Francisco, where he had once been acting adjutant, until the United States entered World War I.

In the early spring of 1917, Bell was transferred to the Department of the East at Fort Jay, Governors Island, in New York City, and as commander of that department, assuming responsibility for Officers' Training Camps created by his predecessor, Leonard Wood, at Plattsburgh, Madison Barracks, and Fort Niagara. Bell's aide, Captain George C. Marshall, was most directly involved in the logistical support for these camps, battling a lethargic army supply system to properly equip the volunteer citizen soldiers. These camps, in August 1917, graduated the large quota of new officers needed for the new National Army and, to a large extent, to officer the new divisions of the east and northeast.

In the same month, Bell was offered and promptly accepted the command of the 77th Division of the National Army, to be organized at Camp Upton, New York. The division was intended to primarily manned by draftees from New York state and featured the Statue of Liberty on its unit patch. Bell commanded the division when the first newly appointed officers climbed the hill and reported to their first assignment, through that formative stage when barracks were thrown together at a miraculous speed, and being filled at the same rate. Then, in December, he sailed for France to make a tour of the front, and observe, first hand, actual fighting conditions. He did not return until the latter part of March 1918.

On his return, Bell failed the physical examination required for active service overseas. When the doctors decreed that he would not take the 77th Division to France, Bell was again given command of the Department of the East, and returned to his old headquarters, Governors Island, which command he held until his death in January 1919. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Medal[19] and interred at Arlington National Cemetery.[20]

Awards and decorations

- Medal of Honor

- Distinguished Service Cross[21]

- Distinguished Service Medal

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Mexican Border Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- Chevalier of the Legion of Honor (France)

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and organization: Colonel, 36th Infantry, U.S. Volunteers. Place and date: Near Porac, Luzon, Philippine Islands, September 9, 1899. Entered service at: Shelbyville, Ky. Born: January 9, 1856, Shelbyville, Ky. Date of issue: December 11, 1899.

- Citation

While in advance of his regiment charged 7 insurgents with his pistol and compelled the surrender of the captain and 2 privates under a close fire from the remaining insurgents concealed in a bamboo thicket.

Dates of rank

![]() United States Military Academy Cadet – class of 1878

United States Military Academy Cadet – class of 1878

| Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Regular Army | 28 June 1878 | |

| Regular Army | 29 December 1890 | |

| Volunteers | 17 May 1898 | |

| Regular Army | 2 March 1899 | |

| Volunteers | 5 July 1899 | |

| Volunteers | 5 December 1899 | |

| Regular Army | 19 February 1901 | |

| Regular Army | 3 January 1907 |

Personal

On January 5, 1881, Bell married Sarah Buford (April 28, 1857 – December 22, 1943) at Rock Island, Illinois. She was the niece of Civil War generals John Buford Jr. and Napoleon Bonaparte Buford.[7][22][23]

See also

References

- ^ a b Pitzer, Andrea (September 19, 2017). One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-30358-3.

- ^ Ltr, Maj Gen J. Franklin Bell to Maj Gen Hugh L. Scott, September 30, 1915, Hugh L. Scott Mss., Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Shelby News, May 10, 1906; E. A. Garlington, "James Franklin Bell," Fiftieth Annual Report of Association of Graduates, United States Military Academy (Saginaw, Mich., 1919), pp. 162–63.

- ^ Ltr, 2d Lt J. Franklin Bell to The Adjutant General, August 9, 1878, Adjutant General Correspondence, 1890–1917, 3773 Appointment, Commission, Promotion (ACP) 78 filed with 937 ACP 79, Record Group (RG) 94, National Archives and Records Service (NARA), Washington, D.C.; Ltr, 2d Lt J. Franklin Bell to Col E. F. Townsend, November 19, 1890, 6842 ACP 90 filed with 937 ACP 79, RG 94, NARA.

- ^ a b c Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York since its establishment in 1802: Supplement, 1890–1900. Vol. IV. The Riverside Press. 1901. pp. 303–304. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York since its establishment in 1802: Supplement, 1920–1930. Vol. VII. R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company, The Lakeside Press. March 1931. p. 153. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b "James Franklin Bell". Fiftieth Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Saginaw, Michigan: Seemann & Peters, Inc., Printers and Binders. June 10, 1919. pp. 163–177. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ CMH Archived June 7, 1997, at the Wayback Machine at www.army.mil

- ^ Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York since its establishment in 1802: Supplement, 1900–1910. Vol. V. Seemann & Peters, Printers. 1910. p. 281. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "The War of 1898 and the U.S.-Filipino War, 1899-1902". Peace History. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ Immerwahr, Daniel (February 19, 2019). How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-71512-0.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. "Concentration Camps Existed Long Before Auschwitz". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ De Bevoise, Ken (1990). "Until God Knows When: Smallpox in the Late-Colonial Philippines". Pacific Historical Review. 59 (2): 149–185. doi:10.2307/3640055. ISSN 0030-8684.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (January 23, 2018). The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-250-15968-7.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (May 20, 2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History (Illustrated ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- ^ Storey, Moorfield; Codman, Julian (1902). Secretary Root's Record:"Marked Severities" in Philippine Warfare.

- ^ Vidal, Gore; Nielsen, David. "Death in the Philippines | David Nielsen".

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Roth, Russel. "Death in the Philippines".

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York since its establishment in 1802: Supplement, 1910–1920. Vol. VI–A. Seemann & Peters, Printers. September 1920. pp. 259–260. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Bell, James Franklin". ANCExplorer. U.S. Army. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Military Times Hall of Valor – Bell was the first person to earn both the MOH and the DSC

- ^ "Bell, J(ames) Franklin". Who's Who in America. A. N. Marquis. 1908. p. 130. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Bell, Sarah B". ANCExplorer. U.S. Army. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

Further reading

- The Philippine "Lodge committee" hearings (A.K.A. Philippine Investigating Committee) and a great deal of documentation were published in three volumes (3000 pages) as S. Doc. 331, 57th Cong., 1st Session An abridged version of the oral testimony can be found in: American Imperialism and the Philippine Insurrection: Testimony Taken from Hearings on Affairs in the Philippine Islands before the Senate Committee on the Philippines-1902; edited by Henry F Graff; Publisher: Little, Brown; 1969. ASIN: B0006BYNI8

- See the extensive Anti-imperialist summary of the findings of the Lodge Committee/Philippine Investigating Committee on wikisource. Listing many of the atrocities and the military and government reaction.

- Ramsey, Robert D. III "A Masterpiece of Counterguerilla Warfare: BG J. Franklin Bell in the Philippines, 1901–1902", The Long War Series: Occasional Paper 25 Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute Press 2007 ISBN 978-0-16-079503-9

- Raines, Edgar F. Jr. "Major General J. Franklin Bell, U.S.A.: The Education of a Soldier, 1856–1899," Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 83 (Autumn 1985): 315–46.

- Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, North Carolina: Pentland Press, Inc. pp. 30–31. ISBN 1-57197-088-6.

External links

- "The Burning of Samar". Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Arlington National Cemetery