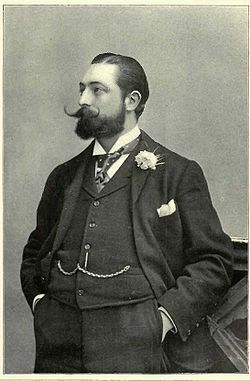

Ivan Caryll

Félix Marie Henri Tilkin[1] (12 May 1861 – 29 November 1921), better known by his pen name Ivan Caryll, was a Belgian-born composer of operettas and Edwardian musical comedies in the English language, who made his career in London and later New York. He composed (or contributed to) some forty musical comedies and operettas.

Caryll's career encompassed three eras of the musical theatre, and unlike some of his contemporaries, he adapted readily to each new development. After composing a few musical burlesques, his first great successes were made in light musical comedies, epitomised by the George Edwardes productions at London's Gaiety Theatre, such as The Shop Girl, The Circus Girl, The Gay Parisienne, and A Runaway Girl. He continued to write musical comedies throughout the next decade, including such hits as The Messenger Boy, The Toreador, The Girl From Kays, The Earl and the Girl, The Orchid, The Spring Chicken, The Girls of Gottenberg and Our Miss Gibbs. He also wrote some operetta scores, such as The Duchess of Dantzic. After this he moved to New York City, where he became an American citizen; his last works, including The Girl Behind the Gun (which became a London hit as Kissing Time), incorporated the new fox-trot and one-step rhythms. At the peak of his career, he had the unparalleled distinction of having five musicals running at the same time in the West End.

Life and career

Caryll was born in Liège, Belgium, the son of Henry Tilkin, an engineer.[2] He studied at the Liège Conservatoire, where he was a fellow student of Eugène Ysaÿe. He then moved to France to study singing at the Paris Conservatoire, where a classmate was Rose Caron.[3] He moved to London in 1882. He was married for a time in the 1890s to Gilbert and Sullivan star Geraldine Ulmar. Later, he married Maud Hill. He had a daughter named Primrose Caryll, who became an actress.

The dashing, moustachioed Caryll was known as one of the best dressed men in London. He was an extravagant spender and a popular and lavish host, entertaining his theatrical friends in princely style. Caryll's free spending ways caused him trouble occasionally, and he had a few narrow escapes from his creditors.[4]

Early career

At first, Caryll earned a poor living by giving music lessons to women in the suburbs.[3] Then he sold some songs to George Edwardes, who eventually hired him as the musical director for the Gaiety and Lyric Theatres. He attempted to raise orchestral standards by banning the deputy system, under which a player who was offered a lucrative engagement could send a substitute to perform in the theatre.[3]

Caryll's first theatre piece was Lily of Léoville in 1886. He sent the score to Camille Saint-Saëns, who used his influence to have it staged at the Bouffes Parisiens.[3] Violet Melnotte secured the English rights, and it was presented in London featuring a young Hayden Coffin.[5] This was followed the same year by Monte Cristo Jr., a burlesque for the Gaiety and then by a number of shows produced for the Lyric, culminating with the very successful Little Christopher Columbus (1893). In 1890, he added numbers to the English-language version of La cigale et la fourmi.[6] Caryll, known as a very expressive conductor, conducted W. S. Gilbert and Alfred Cellier's The Mountebanks at the Lyric in 1892. Cellier died during rehearsals for the piece, and Caryll wrote the overture, the entr'acte, and finished some of the orchestration. His work on the piece received critical praise.[7] Also in 1892, with George Dance, Caryll adapted an opéra comique called Ma mie Rosette, based on a French piece by Paul Lacôme, starring Jessie Bond and Courtice Pounds at the Globe Theatre.[8][9] Caryll recalled of this production that he had been much criticised for adding numbers to Lacome's original score, although Lacome had specially requested him to do so.[3]

Caryll's first big success at the Gaiety was The Shop Girl (1894), which ran for an almost unprecedented 546 performances and heralded a new form of respectable musical comedy in London. The composer conducted the piece himself. Meanwhile, Caryll also had success elsewhere. The Gay Parisienne (1896), written with George Dance, ran for 369 performances at the Duke of York's Theatre, played in New York as The Girl from Paris (281 performances) and toured internationally. At the same time, he continued to compose shows at other theatres, including the comic opera Dandy Dick Whittington (1895), at the Avenue Theatre, with a libretto by George Robert Sims.[10]

Caryll composed the music for almost all the Gaiety musical comedies over the next decade, in collaboration with Lionel Monckton, and also established himself as the most famous conductor of light music in England. Edwardes apparently liked to have the word 'girl' in the titles of the shows, so The Shop Girl was followed by My Girl, The Circus Girl (with over 500 performances in 1896 and 1897) and A Runaway Girl (1898). The Lucky Star was a less successful three-act comic opera (1899, produced by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, based on L'Etoile, an opéra-bouffe by Emmanuel Chabrier). It may have been too risqué for the Savoy Theatre audiences.

Caryll was said to compose very quickly in intense bouts. His scores were noted for swirling waltzes and semi-operatic finales. He often took trips to Paris and elsewhere in search of new musical plays that he could adapt into English. Caryll's output also included songs, dances and salon pieces for his own light orchestra, for which Edward Elgar composed his shapely Serenade Lyrique in 1899.[11]

20th century London pieces

After the turn of the century, Caryll wrote more successful scores, including The Messenger Boy (1900), The Toreador (1901) (with well over 600 performances), The Ladies' Paradise (1901) (libretto by George Dance; the first musical comedy to be presented at the Metropolitan Opera in New York),[12] The Girl From Kays (1902), The Cherry Girl (1902), The Earl and the Girl (1903; another success, starring Walter Passmore and Henry Lytton), The Orchid (1903), and The Duchess of Dantzic (1903), a comic opera based on the story of Napoleon and Madame Sans-Gêne, the washerwoman who married Marshal Lefebvre and became a duchess.[13] During the Christmas season of 1903, he had what was at that time the unparalleled distinction of having five musicals running at the same time in the West End.[2]

Despite these successes, Caryll began to grow jealous of Monckton, who often wrote the most popular numbers in the shows.[4] Still, they continued to work together, producing several successes: The Spring Chicken (1905), The New Aladdin (1906), The Girls of Gottenberg (1907), and the even more popular Our Miss Gibbs (1909), which ran for 636 performances. Typical of the plots of these shows, Our Miss Gibbs concerns a shop girl, courted by an earl in disguise. During this period, Caryll also wrote the less successful The Little Cherub (1906).

Many of Caryll's musicals were given in Paris, Vienna, and Budapest at a time when the English-language musicals were largely ignored on the continent, and he composed original scores for Paris (S.A.R., or Son altesse royale, 1908) and Vienna (Die Reise nach Cuba, 1901).[2]

Broadway musicals

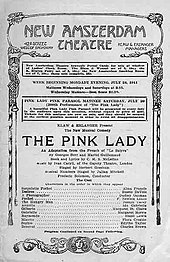

Caryll relocated to New York City in 1910, where he became an American citizen and composed more than a dozen Broadway musicals,[12] including The Pink Lady (1911, with Hugh Morton), Oh! Oh! Delphine!!! (1912), Chin-Chin (1914; including "Ragtime Temple Bells"),[14][15] Jack o'Lantern (1917), and The Girl Behind the Gun (1918, with a book by P. G. Wodehouse and Guy Bolton; the following year, it was a hit in London as Kissing Time). According to Wodehouse, Caryll was widely known as "Fabulous Felix", and "lived en prince ... having apartments in both London and Paris as well as a villa containing five bathrooms overlooking the Deauville racecourse."[16]

Caryll died of a haemorrhage in New York at age 60 while rehearsing the musical Little Miss Raffles, which, contrary to the title of his New York Times obituary,[17] he had not finished composing.[18] It was completed atter his death, with a score mostly by Armand Vecsey, and produced under the title The Hotel Mouse on Broadway in 1922.[19]

Notes

- ^ Gänzl, Kurt (2001). "Ivan Caryll". The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre, Second Edition. Schirmer Books. p. 327. ISBN 0-02-864970-2.

- ^ a b c Gänzl, Kurt, "Caryll, Ivan (1861–1921)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 12 January 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e "A Chat with Mr. Ivan Caryll", Musical Opinion and Music Trade Review, August 1897, p. 756

- ^ a b "Ivan Caryll" Archived 2006-09-06 at the Wayback Machine at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive's British Musical Theatre pages, 24 December 2003, accessed 11 January 2011

- ^ Lily of Leoville at the Guide to Musical Theatre, accessed 29 October 2009

- ^ Traubner, pp. 89–90

- ^ Walker, Raymond J. "Alfred Cellier (1844-1891): The Mountebanks, comic opera (1892); and Suite Symphonique (1878)", Music Web International, 2018

- ^ Moss, Simon. Programmes and descriptions of 1892 productions of Ma mie Rosette, Gilbert & Sullivan, a selling exhibition of memorabilia, Archive: Other items

- ^ "The Theatres", The Times, 27 December 1892, p. 6

- ^ Adams, William Davenport. A Dictionary of the Drama: a Guide to the Plays, Playwrights, Vol. 1, pp. 374–75, Chatto & Windus, 1904

- ^ Profile of Caryll from Musicweb International

- ^ a b Lamb, Andrew, "Caryll, Ivan", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, accessed 12 January 2011 (subscription required); the piece closed quickly and controversially there, with the cast unpaid. See: "The Ladies' Paradise Ends". The New York Times, 29 September 1901

- ^ Information from the Guide to Musical Theatre

- ^ Vocal score of Chin-Chin

- ^ Temple Bells sheet music. The Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, accessed 2 March 2011

- ^ Wodehouse, p. 103

- ^ "Ivan Caryll Dies as he Finishes Play", 30 November 1921, The New York Times, p. 14, accessed 8 August 2008

- ^ Dietz, Dan. The Complete Book of 1920s Broadway Musicals, p. 104–105, Rowman & Littlefield (2019) ISBN 1538112825

- ^ The New York Times, March 14, 1922, p. 20

References

- Hyman, Alan (1978). Sullivan and His Satellites. London: Chappell.

- Traubner, Richard (2003). Operetta: A Theatrical History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96641-2.

- Wodehouse, P.G.; Guy Bolton (1980). Wodehouse on Wodehouse. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-143210-3.

External links

- Works by or about Ivan Caryll at Internet Archive

- Ivan Caryll at the Internet Broadway Database

- Edwardian light opera and musicals site including midi files, lyrics and cast lists for almost 20 Caryll shows

- "'American Chorus Girls Better than English Ones'". New York Times. 10 July 1910. p. SM4. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Listing of Caryll shows - The Guide to Musical Theatre

- Chicago Theater of the Air broadcast of The Pink Lady

- Ivan Caryll discography from Victor

- Free scores by Ivan Caryll at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)