Ismael Montes

Ismael Montes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26th President of Bolivia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 August 1913 – 15 August 1917 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Juan Misael Saracho (1913–1915) José Carrasco Torrico | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Eliodoro Villazón | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | José Gutiérrez Guerra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 August 1904 – 12 August 1909 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Eliodoro Villazón Valentín Abecia Ayllón | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | José Manuel Pando | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Eliodoro Villazón | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Ismael Montes Gamboa 5 October 1861 La Paz, Bolivia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 October 1933 (aged 72) La Paz, Bolivia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Liberal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Bethsabé Montes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Clodomiro Montes Tomasa Gamboa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Higher University of San Andrés | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Bolivia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Bolivian Army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | War of the Pacific

Federal War Acre War Chaco War[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ismael Montes Gamboa (5 October 1861 – 16 October 1933) was a Bolivian general and political figure who served as the 26th president of Bolivia twice nonconsecutively from 1904 to 1909 and from 1913 to 1917. During his first term, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship with Chile was signed on 20 October 1904.

Early life and military career

Montes was born on 5 October 1861, in the city of La Paz, Bolivia. He belonged to a wealthy land-owning family. Montes was the son of General Clodomiro Montes and Tomasa Gamboa.[1]

In 1878, he continued his higher studies by entering the Faculty of Law of the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA), but due to the occupation by the Chilean army of the Bolivian town of Antofagasta on 14 February 1879, Montes decided to leave his studies and enlist as a private in the Murillo Regiment, then belonging to the "Bolivian Legion".[2] In 1880, Montes' regiment was ordered to participate in the Battle of Alto de la Alianza, the last great battle between Bolivia and Chile in the War of the Pacific, in which he participated and barely survived, finishing the battle seriously wounded.[3] Incidentally, he was captured by the Chilean army and remained as a prisoner for the remainder of the war.[citation needed]

Upon his return to Bolivia, due to his heroism during the battle, Montes was directly promoted to the rank of captain by the government.[1] Once Bolivia's participation in the war came to an end in 1880, Montes began working as an instructor in the Bolivian army. However, in 1884, Montes decided to retire from the army to continue with his law studies at the UMSA, which he had left at the beginning of the war. He graduated with a law degree on 12 June 1886.[1][2]

Political career

In 1890, at the age of twenty-nine, Montes was elected as a Deputy representing the Liberal Party (Bolivia), however, his ideology collided with the prevailing conservatism of the time.[4] Montes was elected as the head of Civil Law at the faculty of law in the UMSA.[citation needed]

As a deputy, Montes was known for his elegant and eloquent personality, making him a perfect partner to the vociferous and mercurial Atanasio de Urioste Velasco, another staunch liberal of the time.[5] The two remained friends and allies until the end of their lives.[2]

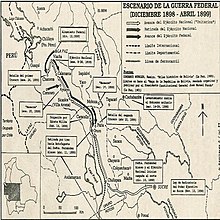

The Civil War of 1898-1899

Prelude and the "Radicatory Law"

Conservative President Severo Fernández wanted to settle the decade-long debate regarding what city was officially the Bolivian capital. Up until 1880, the seat of executive power was wherever the current president resided. Hence, Congress met, between 1825 and 1900, on twenty-nine occasions in Sucre, twenty in La Paz, seven in Oruro, two in Cochabamba and one in Tapacarí. Officially, the capital of Bolivia was Sucre since the presidency of Antonio José de Sucre, remaining as such over the years due to the lack of resources to build a new capital and the influence of its aristocracy. However, by the 1880s, conservative presidents chose to settle in Sucre, making it the de facto capital of the country.[6]

On 31 October 1898, the deputies of Sucre proposed to definitively install the executive capital in Sucre, known as the "Radicatory Law". However, their La Paz counterparts proposed that the Congress should move to Cochabamba (a neutral place), a proposition which was rejected.[7] The liberals seemed to initially accept the plan to make Sucre the official capital. The liberals had done so strategically since if they had vetoed it they would have provoked the inhabitants of the capital, and they knew that if it was approved they could convince the people and the garrison of La Paz (under the orders of Colonel José Manuel Pando) to mount an insurrection. On 6 November there was a massive riot in La Paz: rioters demanded federalism and that their city be made the capital. On 14 November, a Federal Committee was created and chaired by Colonel Pando while its deputies defended their cause in Congress.[6] Three days later, the "Radicatory Law" was approved, making Sucre the official capital and seat of executive power. On 19 November, the new status of the city was officially promulgated.

In response, on 12 December, with the people of La Paz behind them, a Federal Board of Liberals was formed, which included some authority figures who had switched sides (these being the Prefect and Commander General Serapio Reyes Ortiz and the Minister of Instruction Macario Pinilla).[7] Pando's liberals allied themselves with Pablo Zárate Willka, cacique (or 'chief') of the Altiplano.

Outbreak of war

After these events, the deputies from La Paz withdrew by order of the Federal Board. The people of La Paz received their representatives with great fanfare and ceremony.[8] One of the federalists' main objectives then became the overthrow of Fernández. In Sucre, La Paz's pro-Fernández counterpart, there were public demonstrations in support of the government.[7]

Fernández decided to march on La Paz with the three divisions stationed in Sucre (Bolívar, Junín and Hussars). In Challapata, he found out that the rebels had acquired more than two thousand weapons, so he called for the recruitment of volunteers in the capital.[9] Two brigades were formed: the first was made up of the 25 de Mayo battalion and the Sucre squadron. These were made up of upper-class youths with their own horses and weapons, and included the Olañeta battalion and the Monteagudo squadron, made up of young men from popular classes. During their march to reinforce the president, the government's forces plundered the indigenous populations that lived in the countryside.[10]

The government's first brigade encountered Pando and some of his soldiers in Cosmini, and, after being forced to take refuge in the parish of Ayo Ayo, they were massacred on 24 January 1899. In Potosí the population was openly against helping government forces, meanwhile in Santa Cruz and Tarija the populations took a neutral stance. Among the indigenous communities of Cochabamba, Oruro, La Paz, and Potosí there were uprisings in favor of the Liberals.[7]

The decisive battle of the civil war was the battle of the Segundo Crucero, on 10 April 1899, where the president and Pando met. After four hours of combat, Pando's troops emerged victorious. The defeated withdrew to Oruro and, shortly after, Fernández went into exile. During the entire duration of the conflict, Montes remained a loyal partisan to the liberal cause and fought under Pando's command.

After the civil war

Montes attended the Assembly of Oruro, a meeting convened to discuss the future of the country. Once Pando was elected president, Montes was appointed Minister of War of Bolivia and was promoted to colonel.[1] During his time as minister, Montes was concerned with improving the army, subjecting it to greater discipline and equipping it with modern material.[2] Montes also led a military expedition to fight in the north of the country against Brazilian filibusters in the so-called Acre War (1900-1903). After the war, he devoted himself fully to politics, intending to replace José Manuel Pando when his term ended.

In 1904, his party chose him as a candidate for the presidency in the general elections that were to be held that same year. His opponent, Lucio Pérez Velasco, was defeated after a hard-fought election.[11]

President of Bolivia

First term

On 20 October 1904, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship with Chile was signed, which put an end to the state of war between the two countries, not ended since the War of the Pacific because only a truce had been signed in 1884. In the treaty, Montes recognized the absolute and perpetual cession of the Bolivian coast occupied by Chile.[12]

According to Bolivian historiography of the mid-20th century onwards, this treaty was the result of the harassing pressure exerted by Chile on Bolivia (motivated by the expropriation of Chilean and foreign capital that triggered the War of the Pacific), with customs controls and trade restrictions.[13] The liberal governments of Pando and Montes believed that it was time to turn the page with Chile and were convinced that the development of the railways and free transit, stipulated in the treaty, were compensations that were worth the sacrifice.[14] In 1902, Chile had signed a treaty with Argentina that ended their militaristic rivalry with Buenos Aires, reducing its military personnel, creating a compulsory military service law and reducing the number of naval units, meaning that Chile could hardly aspire to exert military pressure on the Montes government.

Montes also signed a trade and customs treaty with Peru in 1905.[2][3] A staunch liberal, Montes established civil marriage, freedom of worship and the abolition of ecclesiastical jurisdiction as fundamental liberties and rights in the Bolivian Constitution.[1] This caused a rupture between the Holy See and the Bolivian government, prompting Pope Pius X to issue the apostolic letter Afflictum propioribus in November 1906. He also modernized the Bolivian Army, managing to bring a French military mission from Europe.

During the general elections of 1908, the government promoted the candidacy of the politician Fernando Eloy Guachalla for President and Eufronio Viscarra for Vice President, a formula that was successful. However, Guachalla fell ill and died shortly before assuming the presidency.[2]

Under the influence of Montes, the liberal majority in Congress denied Vice President Viscarra the right of succession, with Atanasio de Urioste Velasco alleging that the incumbent's death had occurred before he took office, which allowed Montes to be granted a year-long extension to his current term.[1] During the general elections of 1909, the liberal candidate Eliodoro Villazón Montaño, from the Liberal Party, was victorious.

Second term

In 1913, Montes returned to Bolivia from Europe to run again for the presidency of the republic. He won the general elections of 1913 by a wide margin, returning to the presidency for the second nonconsecutive time. Perhaps one of Montes' most important acts as president was the foundation of the Central Bank of the Bolivia, which would be crucial in centralizing the national ecnonomy.[1][2]

During his second term, the dissidence of Liberal Party members increased. Eventually, several liberals defected to Pando's newly founded Republican Party, which the former president had founded in 1914. As the end of his constitutional period approached, Montes promoted the candidacy of the liberal José Gutiérrez Guerra, a childhood friend of his most loyal ally, Atanasio de Urioste.[2] Gutiérrez was triumphant, thus maintaining the hegemony of the Liberal Party.

At the end of his government, Montes became the Bolivian ambassador to France.[1] In 1920, he was still in the city of Paris, when the liberals were ousted from power by the republicans in Bolivia, which forced Montes to remain in France as an exile until 1928, the year in which he returned to assume the leadership of the Liberal Party yet again.[3]

He was President of Central Bank of Bolivia from 1931 to 1933.[15]

The Chaco War and its final years

Throughout his life, Montes had an illustrious military career which began at an early age, initially participating in the War of the Pacific in 1879, then in the Civil War of 1898–1899, and finally in the War of Acre of 1900–1903. These international as well as internal conflicts had given him valuable experiences in acquiring military prestige at the national level for more than fifty years. It is for this reason that during the Chaco War (1932-1935), President Daniel Salamanca decided to commission him as military advisor to the Bolivian army in the Chaco.[1][2]

Montes was unable to witness the outcome nor the conclusion of the war. While he was still serving as military advisor, due to his advanced age, he suddenly died on 16 October 1933, in the city of La Paz.

References

- ^ Military advisor to the Bolivian Army.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Deheza, José A. (1910). El gran presidente [Ismael Montes] (in Spanish). González y Medina.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Prado, Julio Iturri Núñez del (1981). Ismael Montes (in Spanish). Biblioteca Popular Boliviana de "Ultima Hora".

- ^ a b c Klein, Herbert S. (9 December 2021). A Concise History of Bolivia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-84482-6.

- ^ Griewe, Wilhelm Frederick (1913). History of South America from the First Human Existence to the Present Time. Central publishing house.

- ^ Redactor de la h. Cámara de diputados (in Spanish). Imprenta y litografía artistica. 1895.

- ^ a b Lorini, Irma (2006). El nacionalismo en Bolivia de la pre y posguerra del Chaco (1910-1945) (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-63-91-7.

- ^ a b c d Medinaceli, Ximena; Soux, María Luisa (2002). Tras las huellas del poder: una mirada histórica al problema de la conspiraciones en Bolivia (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-64-56-3.

- ^ Pacheco, Mario Miranda (1993). Bolivia en la hora de su modernización (in Spanish). UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-3273-9.

- ^ Manuel, Alcántara; Mercedes, García Montero; Francisco, Sánchez López (1 July 2018). Estudios sociales: Memoria del 56.º Congreso Internacional de Americanistas (in Spanish). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 978-84-9012-925-8.

- ^ Mendieta, Pilar (2010). Entre la alianza y la confrontación: Pablo Zárate Willka y la rebelión indígena de 1899 en Bolivia (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99954-1-338-5.

- ^ Diputados, Bolivia Congreso Nacional Cámara de (1917). Proyectos E Informes (in Spanish). Editorial La Paz.

- ^ Montes, Ismael (1920). Les droits de la Bolivie sur Tacna et Arica: The rights of Bolivia to Tacna and Arica. E. Stanford, Limited.

- ^ A cien años del Tratado de Paz y Amistad de 1904 entre Bolivia y Chile (in Spanish). Fundemos. 2004.

- ^ Millán, Juan Albarracín (2005). La dominación perpetua de Bolivia: la visión chilena de Bolivia en el Tratato [i.e. Tratado] de 1904 (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-63-55-9.

- ^ "Presidentes del Banco Central de Bolivia | Banco Central de Bolivia". www.bcb.gob.bo.