Harmony of the Gospels

| Part of a series on |

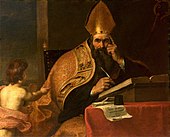

| Augustine of Hippo |

|---|

|

| Augustinianism |

| Works |

| Influences and followers |

| Related topics |

| Related categories |

The Harmony of the Gospels (Latin: De consensu evangelistarum; lit. 'On the Agreement of the Evangelists') is a book by the Christian philosopher Augustine of Hippo.[1] It was written around 400 AD, while Augustine was also writing On the Trinity.[2] In the book, Augustine examines the four canonical Gospels to show that none of them contradicts any of the others.[3]: 157 The book had a major influence in the West on the understanding of the relationships between the four Gospels.[4]: 15

Synopsis

The Harmony of the Gospels is divided into four books. The first book is an extended argument against pagans who claim that Jesus was nothing more than a wise man, and claim that the writers of the Gospels changed his teachings, especially regarding his divinity and the prohibition of worshiping other gods.[5] Though Augustine's exact opponents are unknown, he may have had the Manicheans in mind.[6]: 63–64 He also specifically refers to the Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry, author of the treatise Against the Christians, in connection with these claims.[7]

The other three books are an examination of the four Gospels, using the Gospel of Matthew as a basis, since Augustine believed that it was written first.[3]: 157 In Book II, he compares the other three Gospels to Matthew from the beginning through the Last Supper. He continues this comparison in Book III from the Last Supper until the end of the Gospels. In Book IV, he examines the stories in the other Gospels that have no parallel in Matthew.[5]

Despite its name, the Harmony of the Gospels is not a full Gospel harmony because, except for the Nativity, Augustine does not attempt to provide a single unified text of the disparate Gospel accounts, but rather tries to resolve contradictions that he finds in the Gospels.[8]

Methods

In his comparison of the Gospels, Augustine made use of the Eusebian Canons,[9]: 126 a system of dividing up and comparing the four Gospels created by Eusebius of Caesarea. All but two of the Gospel parallels discussed by Augustine are found in the Canons.[9]: 133 When quoting the Bible, Augustine relied on the recent Latin Vulgate translation by Jerome.[9]: 129

Augustine used various methods to resolve the contradictions he found. Some he resolved by pointing out historical information. For example, to those who wonder how Herod can be alive at Jesus' baptism when he died before Jesus returned from Egypt, Augustine pointed out that those were two different Herods, one of which is the son of the other.[3]: 159

Other times, Augustine tried to solve contradictions by a linguistic analysis, such as showing how one word can have two different meanings, or, alternatively, two different words can mean the same thing.[10]: 151–152 What mattered to Augustine is the meaning that the Evangelist was trying to get across, and not the exact words he uses; differences in words do not matter when the Evangelists clearly intend the same thing.[10]: 158 However, his lack of expertise in the original Greek sometimes undermines his linguistic analysis.[3]: 159

Augustine also made use of textual criticism in examining some contradictions, most notably in his treatment of the apparent misattribution of a prophecy to Jeremiah in Matthew 27. Though previously this misattribution had been attributed to scribal error, Augustine's examination of manuscripts led him to believe that Jeremiah is the original reading.[10]: 157

In situations where the details in the various accounts differ from each other and cannot be reconciled, Augustine held that two distinct albeit similar events or speeches were being recorded; alternatively, if the details differ but do not conflict, that the different evangelists simply chose to note down different details.[3]: 160 [10]: 145 For example, when Mark relates Jesus healing a blind man while leaving Jericho and Luke tells of him healing a blind man while approaching Jericho, Augustine considered these to be two separate miracles.[4]: 33 However, Augustine only resorted to this method if he could find no other solution.[4]: 34

However, when the same events are related in different orders, Augustine held that the order in which the events are narrated are not necessarily the order in which they happened; sometimes the writers narrate events out of order.[11] This difference in order is only a contradiction if the writers intended them to be in the actual order of occurrence.[4]: 31

Relationship between the Gospels

In Book I of the Harmony of the Gospels, Augustine initially upheld the then-traditional view that the Gospels were written in canonical order – that is, Matthew first, followed by Mark, then Luke, then John.[6]: 38 However, while the traditional view held that the four Evangelists wrote independently of the others using Apostolic tradition, Augustine departed from this tradition by claiming that each was aware of and made use of the preceding Gospels, a view which seems to be his own innovation.[4]: 16–17 This view as it pertains to the first three Gospels (the Synoptic Gospels) is now commonly known as the Augustinian hypothesis,[12]: 86–87 which became the consensus view for 1,350 years.[13]: 489

In Book IV, however, he put forth a different view. He claims that it is "more probable" that Mark wrote after Luke, making use of both Matthew and Luke in the composition of his Gospel, a position that is now called the Two-gospel hypothesis.[12]: 86–87 Augustine's support of this theory has now been largely forgotten;[6]: 62 instead, the theory is sometimes known as the Griesbach hypothesis, after its 18th-century proponent Johann Jakob Griesbach.[13]: 490 Francis Watson has noted that "[n]either Griesbach nor most of his recent followers have noticed that Augustine himself came to regard Mark's use of both Matthew and Luke as more probable than his earlier theory."[4]: 15n.3

Augustine also noted that each Gospel has its own overall emphasis: Matthew focuses on Jesus' royalty, Luke deals with his priesthood, and John with his divinity, while Mark, also dealing with his royalty, gives an abbreviated version of Matthew.[2] In the same place, Augustine interprets the four living creatures of Ezekiel and Revelation as the Four Evangelists: Matthew being the lion, Mark the man, Luke the ox, and John the eagle.[12]: 85

References

- ^ Fitzgerald, Allan D., ed. (1999). Augustine Through the Ages: An Encyclopedia. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 132. ISBN 0-8028-3843-X.

- ^ a b Adams, Nicholas (2013). "A Disharmony of the Gospels". In Greggs, Tom; Muers, Rachel; Zahl, Simeon (eds.). The Vocation of Theology Today. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-61097-625-1.

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, Carol (2001). ""Not Words but Things:" Harmonious Diversity in the Four Gospels". In Van Fleteren, Frederick; Schnaubelt, Joseph C. (eds.). Augustine: Biblical Exegete. New York City: Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-2292-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Watson, Francis (2013). Gospel Writing: A Canonical Perspective. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-4054-7.

- ^ a b Schaff, Philip, ed. (1956). Saint Augustin: Sermon on the Mount; Harmony of the Gospels; Homilies on the Gospels. Eerdmans. p. 71.

- ^ a b c Peabody, David (1983). "Part I, Chapter 3. "Augustine and the Augustinian Hypothesis: A Reexamination of Augustine's Thought in De consensu evangelistarum". In Farmer, William R. (ed.). New Synoptic Studies: The Cambridge Gospel Conference and Beyond. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-087-X.

- ^ Wilken, Robert Louis (2003). The Christians as the Romans Saw Them (Second ed.). Yale University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-300-09839-6.

- ^ Barton, John (2007). The Nature of Biblical Criticism. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 14-15. ISBN 978-0-664-22587-2.

- ^ a b c Crawford, Matthew R. (2019). The Eusebian Canon Tables. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880260-0.

- ^ a b c d Gilmore, Allen A. (1946). "Augustine and the Critical Method". The Harvard Theological Review. 39 (2): 141–163. doi:10.1017/S0017816000023142. JSTOR 1508105. S2CID 162717198.

- ^ Van Fleteren, Frederick (2001). "Principles of Augustine's Hermeneutic: An Overview". In Van Fleteren, Frederick; Schnaubelt, Joseph C. (eds.). Augustine: Biblical Exegete. New York City: Peter Lang. p. 16. ISBN 0-8204-2292-4.

- ^ a b c Peabody, David Barrett (2016). "The Two Gospel Hypothesis". In Porter, Stanley E.; Dyer, Bryan R. (eds.). The Synoptic Problem: Four Views. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801049507.

- ^ a b McKim, Donald K., ed. (2007). Dictionary of Major Biblical Interpreters. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2927-9.

External links

The full text of Harmony of the Gospels at Wikisource

The full text of Harmony of the Gospels at Wikisource