Giovanni Battista Palumba

Giovanni Battista Palumba, also known as the Master I.B. with a Bird (or the Bird etc.), was an Italian printmaker active in the early 16th century, making both engravings and woodcuts; he is generally attributed with respectively 14 and 11 of these.[1] He appears to have come from northern Italy, but later worked in Rome.[2] He specialized in subjects from classical mythology,[3] as well as the inevitable religious subjects. Despite his relatively small output, he was a sophisticated artist, whose style shows a number of influences and changes, reflecting awareness of the currents in artistic style at the start of the High Renaissance.[4] The signed prints are usually dated to around 1500–1511.[5]

His earlier name comes from the monogram with which most of his prints are signed, the initials IB followed by a small image of a pigeon-like bird. The Italian word palumbo means 'pigeon' (the Latin name of the common wood pigeon is Columba palumbus), and in Latin the initial for Giovanni ('John' in English) is I, for Iohannes.[6] He is not to be confused with the Master I.B., a German printmaker active in Nuremberg c. 1523–1530.

He is also attributed with various woodcuts for book illustrations from both before and after the 1500s, though all of these are rejected by some, and he is generally accepted as the author of a drawing in the British Museum related to his print of Leda and the Swan, with their Children.

Identification and known biographical facts

Master I.B. with a Bird had long been known, and is catalogued by Bartsch. In the 18th century the famous print collector Pierre-Jean Mariette had already proposed that the monogram hid a name with an avian meaning such as "Joannes Baptista Palumbus",[8] and in 1923 Arthur Mayger Hind speculated: "One thinks of Passeri [sparrow] or Uccello [bird] as possible surnames".[9] In the 19th century an artist from Modena called Giovanni Battista del Porto was believed by many to be Master I.B. with a Bird. In the 1930s James Byam Shaw, who published on the prints, thought he might be Jacopo Ripanda, known as a painter and designer of antiquarian prints from Bologna, who mixed in the Roman humanist milieu that the prints reflect; ripanda is an Italian term for a water-bird.[10]

- Examples of the monogram

-

Rape of Europa, see below

-

Personification of Roma, see below

-

Leda and the Swan, with their Children, see below

The question was settled in 1936 when Augusto Campana published a gloss in a manuscript of poetry by Evangelista Maddeleni dei Cappodiferro in the Vatican Library which identified Palumba by referring to his print of Leda and the Swan, and this identification is now universally accepted.[11] Campana dated the epigram on the Leda to 1503, based on the sequence in the manuscript, but Konrad Oberhuber argues for a date around 1508–10, based on the style of the print itself, and its closeness to datable prints of that period by Marcantonio Raimondi.[12]

Identifying Master I.B. with a Bird with Palumba brought almost no extra biographical information, as there are no other documentary records with the name.[13] The same Vatican manuscript credits Palumba with a painted portrait of a Sicilian servant, perhaps of Cardinal Giovanni Colonna (1456–1508). A Pietro Paolo Palumba, who published prints in Rome dated between 1559 and 1584, describes himself as "Palumbus successor Palumbi".[14]

Extrapolating from the stylistic influences visible in the prints, he is believed to have had a background in or close to Milan or Bologna, with some claiming unsigned woodcut book illustrations published there or in Saluzzo between 1490 and 1503 are by him.[15] Hind thought that one early engraving "with its niello-like background, suggests a goldsmith's education," and that "it seems rash to dogmatize on the locality of so eclectic a spirit"[16] Goldsmithing was a common background for engravers as the technique was first used on metalwork, and formed part of their normal training. This early period was followed by a move to Rome by about 1503; one print shows some "freaks of nature" that were news there in 1503.[17] The dates estimated for his independent prints finish around 1510,[18] though the portraits in Illustrium Imagines would have been from some years later, if they are his.

Palumba has also been suggested as the author of the long series of imagined profile head portraits of famous people in Andrea Fulvio's Illustrium Imagines (1517), though this idea has been rejected by other writers.[19] He was proposed by Campana as the author of other woodcut book illustrations published in Venice and Siena between 1521 and 1524, though A.M. Hind disagreed. Oberhuber concludes that "It seems to be clear, at least, that after about 1510–11 Palumba's production of single woodcuts and engravings ceases".[20]

A drawing in the British Museum of Leda and the Swan, with their Children had been attributed to Giorgione, Sodoma, and "Anonymous: Milanese School", before Hind's attribution to Palumba was generally accepted. The composition is very similar to the engraving of the same subject (in reverse), as are the style and mood, though the background and minor details in the poses of the figures are different.[21]

Prints and style

Engravers generally worked the plates for their designs at this period, and it is assumed Palumba did the same. Conversely, like many or most designers of woodcuts, he probably did not cut the blocks himself; some of his woodcuts have other initials, presumably those of specialist block-cutters.[22] He seems to have practised both techniques throughout the period of the prints with monograms.[23] There is a single late chiaroscuro woodcut of Saint Sebastian, with one line and one tone block; this is very early for Italy, and a "truly pictorial" print.[24]

Many of the prints taken to be relatively early show clear debts, especially in the landscape backgrounds, to the prints of Albrecht Dürer, especially those from the last five years of the 15th century; these were widely circulated in north Italy and had a strong and immediate influence on many printmakers.[25] The religious subjects are mostly regarded as early, a woodcut of the Crucifixion having many similarities to Andrea Solari's painting (now Louvre) made in Milan in 1503.[26]

Apart from Dürer, who is invariably the first named, many other artists are mentioned as influences: Andrea Mantegna, Nicoletto da Modena, the Bolognese school in general, Sodoma, Baldassare Peruzzi, Francesco Francia,[27] Marcantonio Raimondi, Andrea Solario, Venetian sculpture, Cesare da Sesto, Pollaiuolo, Cristofano Robetta, Filippino Lippi, Pinturicchio, Jacopo Ripanda, and Luca Signorelli.[28] Oberhuber echoes Hind in calling him "extremely eclectic, but he always appropriates his motifs in such a way that the sources are not easy to identify".[29] His borrowings from Leonardo are discussed below. In turn Leo Steinberg gives the Family of Fauns as the earliest appearance of the "slung leg" motif "in its canonic form"; he traces this motif, representing sexual intimacy, to the later works of Raphael and Michelangelo.[30]

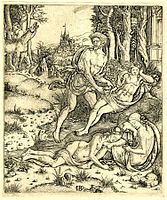

A number of the prints follow the fashion for imagining the varieties of humanoids of classical mythology in their family lives, already set by Dürer, Jacopo de' Barbari and others. Palumba's prints include families of tritons, fauns, and satyrs, though in most the females and children appear anatomically human. These and other prints "reflect the taste for the antique, mixed with a feeling for the bizarre and delicately beautiful" of Filippino Lippi, Pinturicchio, Peruzzi and Ripanda.[31] He is also interested in Ovidian transformations, with two prints of Leda, and others of Europa being carried off, and Actaeon half-transformed.

The approximate chronology proposed by Friedrich Lippmann in a paper of 1894 on the woodcuts has remained largely accepted, and Oberhuber is content to add the engravings to it. The prints are divided into chronological stages or groups, A to E.[32]

His woodcuts have been described, by Mark McDonald, as "amongst the most important produced in Italy (Rome) during the early years of the sixteenth century",[33] but most Italian makers of independent prints (as opposed to book illustrations) preferred to use engraving.[34] Exceptions include Titian, who experimented with woodcuts (executed by others, but with his encouragement) in these years. One link between the two artists is the unusual size of their woodcuts. At 270 x 445 mm and carved on a single block, Atalanta and Meleager hunting the Calydonian boar takes the woodcut near the edge of what is technically feasible; most woodcuts this size use multiple blocks. There was a fashion, mostly in Germany, for even larger woodcuts that were conceived as murals, either pasted to walls or mounted on textiles like Chinese paintings.[35]

-

Crucifixion of Christ, woodcut

-

Prudence, or Foresight, engraving

-

Rape of Europa, engraving

-

Diana and Actaeon, woodcut

-

A family of fauns, engraving

-

Vulcan forging, with Mars, Venus and Cupid, woodcut

-

Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, engraving

-

Saint Jerome, with lion

Leda and Leonardo

Leda and the Swan was a subject that fitted Palumba's taste in subjects, and he engraved it twice; it was fashionable in the period, and a number of artists made depictions. The first is grouped in Lippmann's stage D, perhaps from around 1508, and shows the couple making love enthusiastically in a landscape. The second is from stage E, perhaps around 1510, and is one of his last and most highly praised prints. The British Museum drawing clearly relates to the print, and is "tentatively attributable to Master I.B.'s own hand".[36]

Leda had also been a preoccupation of Leonardo da Vinci, who also worked on "a series of themes and variations on the subject of Leda and her children",[37] centering on two compositions, in the approximate period 1503–1510; these both featured the children in some versions. Neither survive as paintings by Leonardo, but there are a number of drawings for both by him, and copies in oils, especially of the second composition, where Leda stands.[38] Neither of Palumba's compositions borrow directly from Leonardo, but the second "appropriates the stylistic ideals created by Leonardo",[39] and "in its final form, represents a harmonious fusion of Leonardo and Dürer".[40] According to Vasari, Leonardo's disciple Cesare da Sesto was in Rome, probably around 1508–09, which is one possible route for Palumba's apparent awareness of Leonardo's designs.[41]

In the drawing the background is a Dürer-esque clump of trees and rocks, but in the print this is replaced by the famous Roman ruin known as the Temple of Minerva Medica, in fact a nymphaeum, given an invented coastal setting.[42] In the print "the classically inspired female nude and accompanying putti [the children] arrange themselves into the sort of tightly knit pyramidal configuration universally associated with principles of Italian High Renaissance design".[43]

-

Leda and the Swan, engraving

-

Leda and the Swan, with their Children, engraving

-

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Kneeling Leda, drawing

Notes

- ^ Oberhuber, 440; Zucker, 74 and note. There are minor discrepancies, with both of these rejecting an engraving of Venus and Cupid.

- ^ Zucker, 74–75

- ^ Oberhuber, 442

- ^ Hind (1935), 440; Zucker, 75

- ^ Oberhuber, 445; Zucker, 75; BM says "1500–1520" in the biographical details, but 1500–1510 or −1515 for individual prints.

- ^ Oberhuber, 440; Landau, 102

- ^ McDonald, 112

- ^ Oberhuber, 440

- ^ Hind (1923)

- ^ Oberhuber, 441; BM; Landau, 100; Hind (1935), 439–440; Zucker, 74

- ^ Oberhuber, 440–441 – The manuscript gave various characters nicknames, the actual names being given in notes in the margins. There was an epigram "Of Leda printed by Dares", with Palumba named in the margin; BM

- ^ Oberhuber, 441

- ^ Zucker, 74

- ^ Oberhuber, 440

- ^ Oberhuber, 440–443

- ^ Hind, 1923, 60; the print

- ^ Oberhuber, 440

- ^ Oberhuber, 452

- ^ "There is not a single bit of written or printed source material that links Giovanni Battista Palumba to the portraits in Andrea Fulvio's Illustrium Imagines. The question remains with us as to how an art historian can link the aerated style of Palumba in the larger pictures with the dense black and white sketchy portraits in the Illustrium Imagines...", Spink Numismatic Circular, Volume 108, 2000

- ^ Oberhuber, 445

- ^ Oberhuber, 450–453; Zucker, 75; British Museum, the drawing

- ^ Hind (1935), 442

- ^ Oberhuber, 443–445

- ^ Oberhuber, 444, quoted; Hind (1935), 442; Landau, 150–153

- ^ Oberhuber, 441–442, 446; Hind (1935), 440; McDonald, 110; Zucker, 75

- ^ Oberhuber, 442; Hind (1935), 443; the painting

- ^ Hind (1923), 60; Hind (1935), 440

- ^ Oberhuber, 441–442

- ^ Oberhuber, 442

- ^ Steinberg, Leo. “Michelangelo's Florentine Pietà: The Missing Leg.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 50, no. 4, 1968, (pp. 343–353) p. 350, JSTOR.

- ^ Oberhuber, 442–443

- ^ Oberhuber, 443–445

- ^ McDonald, 110

- ^ Antony Griffiths, Prints and Printmaking, p. 20, 1996, British Museum Press, 2nd edn, ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- ^ Landau, 150, 231–237, 300

- ^ Zucker, 74–75 (75 quoted); Oberhuber, 444

- ^ Zucker, 75

- ^ Oberhuber, 450–451

- ^ Oberhuber, 445 (quoted), 450

- ^ Zucker, 75

- ^ Oberhuber, 450–451

- ^ Zucker, 75; Oberhuber, 452

- ^ Zucker, 75

References

- "BM": British Museum, "Giovanni Battista Palumba (Biographical details)"

- AM Hind (1923), A History of Engraving and Etching, 1923, Houghton Mifflin Co., reprinted Dover Publications, 1963, ISBN 0-486-20954-7

- AM Hind (1935), An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Volume II, 1935, Houghton Mifflin Co., reprinted Dover Publications 1963, ISBN 0-486-20953-9

- Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- McDonald, Mark, Ferdinand Columbus, Renaissance Collector, 2005, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-2644-9

- Oberhuber, Konrad, in: Jay A. Levinson (ed.) Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Catalogue), 1973, LOC 7379624

- Zucker, Mark J., in K.L. Spangeberg (ed), Six Centuries of Master Prints, Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993, ISBN 0-931537-15-0

Further reading

- AM Hind, 'Early Italian Engraving', vol.V, 1948 (16 nos catalogued)