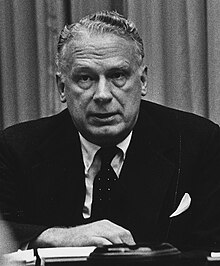

George Ball (diplomat)

George Ball | |

|---|---|

| |

| 7th United States Ambassador to the United Nations | |

| In office June 26, 1968 – September 25, 1968 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Arthur Goldberg |

| Succeeded by | James R. Wiggins |

| 23rd United States Under Secretary of State | |

| In office December 4, 1961 – September 30, 1966 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Chester Bowles |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Katzenbach |

| Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs | |

| In office February 1, 1961 – December 3, 1961 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy |

| Preceded by | C. Douglas Dillon |

| Succeeded by | Thomas C. Mann |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Wildman Ball December 21, 1909 Des Moines, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | May 26, 1994 (aged 84) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Education | Northwestern University (BS, JD) |

George Wildman Ball (December 21, 1909 – May 26, 1994) was an American diplomat and banker. He served in the management of the US State Department from 1961 to 1966 and is remembered by most as the only cabinet member of Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson who was a major dissenter against the escalation of the Vietnam War. Ball advised against deploying U.S. combat forces, as he believed it would lead the United States into an unwinnable war and result in a prolonged conflict. Instead, he argued that the United States should prioritize allocating its resources to Europe rather than engaging in expensive military ventures. He refused to publicize his doubts. He helped determine American policy regarding trade expansion, Congo, the Multilateral Force, de Gaulle's France, Israel and the rest of the Middle East, and the Iranian Revolution.

Early life and education

Ball was born in Des Moines, Iowa. He lived in Evanston, Illinois, and graduated from Evanston Township High School and Northwestern University with a Bachelor of Science (BS) and a Juris Doctor (JD). Ball joined a Chicago law firm in which Adlai Stevenson II was one of the partners, and became a protégé of Stevenson.

Early career

During 1942, he became an official of the Lend Lease program. During 1944 and 1945, he was director of the Strategic Bombing Survey in London.[1]

During 1945, Ball began collaboration with Jean Monnet and the French government in its economic recovery in its negotiations regarding the Marshall Plan. In 1946, Ball co-founded the law firm of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, along with Henry J. Friendly, later the chief judge of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.[2] During 1950 he helped draft the Schuman Plan and the European Coal and Steel Community Treaty.

Ball had a major role in Stevenson's presidential campaign during 1952. He was the liaison between Stevenson and President Truman and helped publicize Stevenson's opinions in major magazine articles. He was also the executive director of the Volunteers For Stevenson, concerned mainly with enlisting independent and Republican voters. He was also a speechwriter in the Stevenson campaign. Ball likewise had a major role in Stevenson's 1956 presidential campaign and unsuccessful 1960 bid to gain the Democratic nomination.[3]

State Department

Ball was the Under Secretary of State for Economic and Agricultural Affairs for the administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He is known for his opposition to escalation of the Vietnam War.

After Kennedy decided to send 16,000 "trainers" to Vietnam, Ball, the one dissenter in Kennedy’s entourage, pleaded with JFK to recall France’s devastating defeat in 1954 at Dien Bien Phu and throughout Indochina. Ball raised the question with President Kennedy. (November 7, 1961) "Within five years we'll have 300,000 men in the paddies and jungles and never find them again. That was the French experience. Vietnam is the worst possible terrain both from a physical and political point of view."[4][note 1] In response to this prediction, the President seemed unwilling to discuss the matter, responding with an overtone of asperity: "George, you're just crazier than hell. That just isn't going happen."[6] As Ball later wrote, Kennedy's "statement could be interpreted in two ways: either he was convinced that events would so evolve as not to require escalation, or he was determined not to permit such escalation to occur."[7]

Ball was one of the endorsers of the 1963 coup which resulted in the death of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother.

As President Johnson was urged by his closest foreign policy and defense advisors to initiate a sustained bombing campaign against North Vietnam during the winter of 1964–1965, Ball forcefully warned Johnson against such an action. In a February 24, 1965, memorandum he passed to the President through his aide Bill Moyers, Ball provided an accurate analysis of the situation in South Vietnam, and of the U.S. stake in it, as well as a startlingly prescient description of the disaster any escalation of American involvement would entail. Urging Johnson to re-examine all the assumptions inherent in the arguments for increasing U.S. involvement, Ball stood alone among the upper echelons of Johnson's policymakers when he attacked the prevailing notion, virtually unquestioned at the time in Washington, that America's fundamental strategic interest in escalating the conflict was in protecting U.S. international prestige and the reliability of its commitments to allies.

He observed that other international actors, including both allies and enemies, were concerned not whether the U.S. could live up to its promise but rather whether the U.S. could avert a disaster in time instead of squandering strategic capital in a struggle to assist a failed regime. If the U.S. continued in its course, Ball argued, U.S. loyalty would be less questioned than U.S. strategic judgement would. Although Johnson considered the memorandum seriously, Ball had waited too long to deliver it. The decision had already been made, and sustained U.S. bombing operations against North Vietnam commenced on March 2, 1965.[8]

Ball also served as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations from June 26 to September 25, 1968. During August 1968 at the UN Security Council, he endorsed the Czechoslovaks' struggle against the Soviet invasion and their right to live without dictatorship.

During the Nixon administration, Ball helped draft American policy proposals on the Persian Gulf.

Arguments

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Ball was long a critic of Israeli policies toward its Arab neighbors. He "called for the recalibration of America’s Israel policy in a much noted Foreign Affairs essay" during 1977[9] and, during 1992, co-authored The Passionate Attachment with his son, Douglas Ball. The book argued that American aid to Israel has been morally, politically and financially costly, and described the weaponization of antisemitism for political purposes.[10] Elsewhere in the book, referring to the Israeli attack on the USS Liberty, Ball asserted, "... the ultimate lesson of the Liberty attack had far more effect on policy in Israel than in America. Israel's leaders concluded that nothing they might do would offend the Americans to the point of reprisal. If America's leaders did not have the courage to punish Israel for the blatant murder of American citizens, it seemed clear that their American friends would let them get away with almost anything."[11][12][13]

He often used the aphorism (perhaps originally invented by Ian Fleming in the novel Diamonds Are Forever) "Nothing propinks like propinquity," later dubbed the Ball Rule of Power.[14] It means that the more direct access one has to the president, the greater one's power regardless of title.

Ball was an advocate of free trade, multinational corporations and their theoretical ability to neutralize what he considered to be "obsolete" nation states. Until and after his ambassadorship, Ball was employed by the banking company Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb. He was a senior managing director at Lehman Brothers until his retirement during 1982.[15] Ball was among the first North American members of the Bilderberg Group, attending every meeting except for one before his death.[16] He was a member of the Steering Committee of the group.[17]

Death

Ball died in New York City on May 26, 1994. He was buried in Princeton Cemetery.

Popular culture

George Ball was portrayed by John Randolph in the 1974 made-for-TV movie The Missiles of October, by James Karen in the 2000 movie Thirteen Days and by Bruce McGill in the 2002 TV movie Path to War.

Books

- The Passionate Attachment: America's Involvement With Israel, 1947 to the Present, with Douglas B. Ball, ISBN 0-393-02933-6.

Media

Appearances

- Cuban Missile Crisis Revisited. Produced for The Idea Channel by the Free to Choose Network, 1983.

- Phase II, Part I (U1016) (June 27, 1983)

- Featuring McGeorge Bundy, Richard Neustadt, Robert S. McNamara & U. Alexis Johnson in Washington D.C.

- Phase II, Part II (U1017) (June 27, 1983)

- Featuring McGeorge Bundy, Richard Neustadt, Robert S. McNamara & U. Alexis Johnson in Washington D.C.

- Phase II, Part I (U1016) (June 27, 1983)

See also

Explanatory notes

References

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (May 28, 1994). "George W. Ball Dies at 84; Vietnam's Devil's Advocate". The New York Times.

- ^ "George Clear, 90, Law Firm Founder". The New York Times. March 27, 1981.

- ^ Eleonora W. Schoenebaum, ed. Political Profiles: The Truman Years (1978) pp 19-22

- ^ George Ball, The Past Has Another Pattern, Memoirs, (New York, Norton, 1982), p366. Polner, Murray (March 1, 2010), "Left Behind: Liberals get a war president of their very own", The American Conservative, archived from the original on September 20, 2010, retrieved September 15, 2018

- ^ DiLeo, David L. (1991). George Ball, Vietnam, and the Rethinking of Containment. Univ. of N. Carolina Pr. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8078-4297-3. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ George Ball, The Past Has Another Pattern, Memoirs, (New York, Norton, 1982), p366.

- ^ George Ball, "The Past Has Another Pattern: Memoirs," 1982, p. 367.

- ^ VanDeMark, Brian (1991). Into the Quagmire: Lyndon Johnson and the Escalation of the Vietnam War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0195065069.

- ^ McConnell, Scott (2007-12-03) The Lobby Strikes Back Archived July 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The American Conservative

- ^ Curtiss, Richard H. (July–August 1994). "In Memoriam: George Ball's Mideast Views Were Muffled by U.S. Media". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. p. 20.

- ^ Ball, George W.; Ball, Douglas B. (1992). The Passionate Attachment: America's Involvement with Israel 1947 to the Present. W.W. Norton. p. 58. ISBN 0-393-02933-6.

- ^ https://www.wrmea.org/1999-december/the-israeli-attack-on-the-uss-liberty-june-8-1967-and-the-32-year-cover-up-that-has-followed.html

- ^ "The U.S.S. Liberty and the culture of impunity". June 2010.

- ^ Sidey, Hugh (October 17, 1983). "Learning How to Build a Barn". Time. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008.

- ^ George Ball : Alumni Exhibit: Northwestern University Archives

- ^ "George W. Ball Papers, 1880s–1994: Finding Aid". Princeton University Library. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010.

- ^ "Former Steering Committee Members". bilderbergmeetings.org. Bilderberg Group. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

Further reading

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Dileo, David L. (1991). George Ball, Vietnam, and the Rethinking of Containment. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4297-4.

- Bill, James A. (1997). George Ball: Behind the Scenes in U.S. Foreign Policy. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300069693.

- Brands Jr, H. W. "America enters the Cyprus tangle, 1964." Middle Eastern Studies 23.3 (1987): 348–362. online

Primary sources

- Ball, George W. (1983). The Past Has Another Pattern: Memoirs. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30142-7.

External links

- George W. Ball Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- Cold War International History Project's Cold War Files at the Wayback Machine (archived 2011-11-16)

- Bio at Northwestern University

- Bio at Montgomery Endowment

- Profile: George Ball at the Wayback Machine (archived 2004-12-18) – The Center for Cooperative Research

- Memorandum for the President from George Ball, "A Compromise Solution in South Vietnam" Archived July 9, 2009, at the Portuguese Web Archive

- Memo from George Ball to McNamara Archived September 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Works by George Ball at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Personal papers at National Archives Records at the Wayback Machine (archived 2006-03-08)

- Personal papers at Princeton University at the Wayback Machine (archived 2006-09-06)

- George W. Ball. How to save Israel in spite of herself, Foreign Affairs, The Council on Foreign Relations, April 1977.

- George W. Ball. The Coming Crisis in Israeli-American Relations, Foreign Affairs, The Council on Foreign Relations, Winter 1979.

- George W. Ball. The conduct of American foreign policy, Foreign Affairs, The Council on Foreign Relations, 1980.

- James A. Bill. George Ball: Behind the Scenes in U.S. Foreign Policy

- Robert Dallek. George Ball: Behind the Scenes in U.S. Foreign Policy, The Washington Monthly, July 1997.

- William Engdahl. George Ball's role in the 1979 Iranian Revolution Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Payvand News, March 10, 2006.

- Book review of biography on George Ball

- Oral History Interviews with George Ball, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2001-11-16)

- Interview with George W. Ball, 1981, on the Vietnam War at the Wayback Machine (archived 2010-12-21) – WGBH Open Vault

- Appearances on C-SPAN