France–Africa relations

France–Africa relations cover a period of several centuries, starting around in the Middle Ages, and have been very influential to both regions.

First exchanges (8th century)

Following the invasion of Spain by the Berber Commander Tariq ibn Ziyad in 711, during the 8th century Arab and Berber armies invaded Southern France, as far as Poitiers and the Rhône valley as far as Avignon, Lyon, Autun, until the turning point of the Battle of Tours in 732.[1]

Cultural exchanges followed. In the 10th century, the French monk Gerbert d'Aurillac, who became the first French Pope Sylvester II in 999, traveled to Spain to learn about Islamic culture, and may even have studied at the University of Al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco.[2]

France would become again threatened by the proximity of the expanding Moroccan Almoravid Empire in the 11th and 12th centuries.[3]

Early French explorations (14–15th century)

According to some historians, French merchants from the Normandy cities of Dieppe and Rouen traded with the Gambia and Senegal coasts, and with the Ivory Coast and the Gold Coast, between 1364 and 1413.[4][5] Probably as a result, an ivory-carving industry developed in Dieppe after 1364.[6] These travels however were soon forgotten with the advent of the Hundred Years War in France.[6]

In 1402, the French adventurer Jean de Béthencourt left La Rochelle and sailed along the coast of Morocco to conquer the Canary islands.[7]

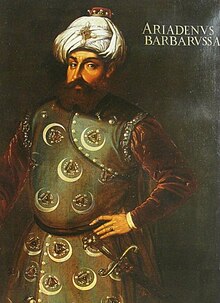

Barbary States

Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt

France signed a first treaty or Capitulation with the Mamluk Sultanate in 1500, during the rules of Louis XII and Sultan Bajazet II,[8][9] in which the Sultan of Egypt made concessions to the French and the Catalans.

Important contacts between Francis I of France and the Ottoman Emperor Suleiman the Magnificent were initiated in 1526, leading to a Franco-Ottoman alliance. This alliance soon created close contacts between France and the Barbary States of Northern Africa, which were in the process of becoming vassals to the Ottoman Empire. In 1533, the first Ottoman embassy to France was led by Hayreddin Barbarossa, then head of the Barbary States in Algiers.

Suleiman ordered Barbarossa to put his fleet at the disposition of Francis I to attack Genoa and the Milanese.[10] In July 1533 Francis received Ottoman representatives at Le Puy, and in return he dispatched Antonio Rincon to Barbarossa in North Africa and then to Suleiman in Asia Minor.[11]

Various military actions were also coordinated during the Italian War of 1551–1559. In 1551, the Ottomans, accompanied by the French ambassador Gabriel de Luez d'Aramon, succeeded in the Siege of Tripoli.[12]

Morocco

In 1533, Francis I sent Colonel Pierre de Piton as ambassador to Morocco, thus initiating official France-Morocco relations.[13] In a letter to Francis I dated August 13, 1533, the Wattassid ruler of Fes, Ahmed ben Mohammed, welcomed French overtures and granted freedom of shipping and protection of French traders.

France started to send ships to Morocco in 1555, under the rule of Henry II, son of Francis I.[14] As early as 1577, France established a consul in Fez, Morocco, in the person of Guillaume Bérard, the first European country to do so.[15][16] Bérard was succeeded by Arnoult de Lisle and then Étienne Hubert d'Orléans in the position of physician and representative of France at the side of the Sultan. These contacts with France occurred during the landmark rules of Abd al-Malik and his successor, Moulay Ahmad al-Mansur.

In order to continue the exploration efforts of his predecessor Henry IV, Louis XIII considered a colonial venture in Morocco and sent a fleet under Isaac de Razilly in 1619.[17] Razilly was able to reconnoiter the coast as far as Mogador. In 1624, he was put in charge of an embassy to the pirate harbour of Salé in Morocco, in order to solve the affair of the library of Mulay Zidan.[18]

In 1630, Razilly was able to negotiate the purchase of French slaves from the Moroccans. He visited Morocco again in 1631 to participate in the negotiation of the Franco-Moroccan Treaty (1631).[19] This treaty gave France preferential treatment, known as Capitulations: advantageous tariffs, the establishment of a consulate, and freedom of religion for French subjects.[20]

Senegal (1659)

In 1659, France established the trading post of Saint-Louis, Senegal. The European powers continued contending for the island of Gorée, until in 1677, France led by Jean II d'Estrées during the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678) ended up in possession of the island, which it would keep for the next 300 years.[21] In 1758 the French settlement was captured by a British expedition as part of the Seven Years' War, but was later returned to France in 1783.

Maghreb

French conquest of Algeria (1830)

The French conquest of Algeria took place from 1830 to 1847, resulting in the establishment of Algeria as a French colony. Algerian resistance forces were divided between forces under Ahmed Bey at Constantine, primarily in the east, and nationalist forces in Kabylie and the west. Treaties with the nationalists under `Abd al-Qādir enabled the French to first focus on the elimination of the remaining Ottoman threat, achieved with the 1837 Capture of Constantine. Al-Qādir continued to give stiff resistance in the west. Finally driven into Morocco in 1842 by large-scale and heavy-handed French military action, he continued to wage a guerilla war until Morocco, under French diplomatic pressure following its defeat in the First Franco-Moroccan War, drove him out of Morocco. He surrendered to French forces in 1847.

First Franco-Moroccan War (1844)

France again showed a strong interest in Morocco in the 1830s, as a possible extension of her sphere of influence in the Maghreb, after Algeria and Tunisia. The First Franco-Moroccan War took place in 1844, as a consequence of Morocco's alliance with Algeria's Abd-El-Kader against France. Following several incident at the border between Algeria and Morocco, and the refusal of Morocco to abandon its support to Algeria, France faced Morocco victoriously in the Bombardment of Tangiers (August 6, 1844), the Battle of Isly (August 14, 1844), and the Bombardment of Mogador (August 15–17, 1844).[22] The war was formally ended September 10 with the signing of the Treaty of Tangiers, in which Morocco agreed to arrest and outlaw Abd al-Qādir, reduce the size of its garrison at Oujda, and establish a commission to demarcate the border. The border, which is essentially the modern border between Morocco and Algeria, was agreed in the Treaty of Lalla Maghnia.

Algeria 1958

The May 1958 seizure of power in Algiers by French army units and French settlers opposed to concessions in the face of Arab nationalist insurrection ripped apart the unstable Fourth Republic. The National Assembly brought him back to power during the May 1958 crisis. De Gaulle founded the Fifth Republic with a strengthened presidency, and he was elected in the latter role. He managed to keep France together while taking steps to end the war, much to the anger of the Pieds-Noirs (Frenchmen settled in Algeria) and the military; both previously had supported his return to power to maintain colonial rule. De Gaulle granted independence to Algeria in 1962.[23]

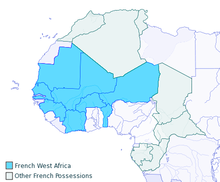

French West Africa

From 1880, France endeavoured to build a railway system, centered on the Saint-Louis-Dakar line that involved taking military control of the surrounding areas, leading to the military occupation of mainland Senegal.[24] The construction of the Dakar-Niger Railway also began at the end of the 19th century under the direction of the French officer Gallieni.

The first Governor General of Senegal was named in 1895, overseeing most of the territorial conquests of Western Africa, and in 1904, the territories were formally named French West Africa (AOF: "Afrique Occidentale Française"), of which Senegal was a part and Dakar its capital.

Sub-Saharan Africa 1940–1981

French conservatives were disillusioned with the colonial experience after the disasters in Indochina and Algeria. They wanted to cut all ties to the numerous colonies in French sub-Saharan Africa. During the war, de Gaulle had successfully based his Free France movement and the African colonies. After a visit in 1958, he made a commitment to make sub-Saharan French Africa a major component of his foreign-policy.[25] All the colonies in 1958, except Guinea, voted to remain in the French Community, with representation in Parliament and a guarantee of French aid. In practice, nearly all the colonies became independent in the late 1950s, but maintained very strong connections.[26] Under close supervision from the president, French advisors played a major role in civil and military affairs, thwarted coups, and, occasionally, replaced upstart local leaders. The French colonial system had always been based primarily on local leadership, in sharp contrast to the situation in British colonies. The French colonial goal had been to assimilate the natives into mainstream French culture, with a strong emphasis on the French language. From de Gaulle's point of view, close association gave legitimacy to his visions of global client grandeur, certified his humanitarian credentials, provided access to oil, uranium and other minerals, and provided a small but steady market for French manufacturers. Above all it guaranteed the vitality of French language and culture in a large slice of the world that was rapidly growing in population. De Gaulle's successors Georges Pompidou (1959–74) and Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1974–1981) continued de Gaulle's African policy. It was supported with French military units, and a large naval presence in the Indian Ocean. Over 260,000 Frenchmen worked in Africa, focused especially on delivering oil supplies. There was some effort to build up oil refineries and aluminum smelters, but little effort to develop small-scale local industry, which the French wanted to monopolize for the mainland. Senegal, Ivory Coast, Gabon, and Cameroon were the largest and most reliable African allies, and received most of the investments. [27] During the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), France supported breakaway Biafra, but only on a limited scale, providing mercenaries and obsolete weaponry. De Gaulle's goals were to protect its nearby ex-colonies from Nigeria, to stop Soviet advances, and to acquire a foothold in the oil-rich Niger delta.[28]

Mitterrand: 1981–1996

Socialist rhetoric had long attacked the imperialistic program of the French overseas empire, and its continuity in Francophone Africa after those states gained independence. Socialist president François Mitterrand (1981–1996) ignored that old rhetoric, and maintained the benevolent French supervision of the former colonies. However, unlike his predecessors who maintained strong ties with South Africa, Mitterrand denounced the crimes of Apartheid.[29]

Gabon

Mitterrand paid special attention to Gabon because of its strategic location and important economy. Mitterrand generally supported the regime of Gabon's president Omar Bongo, who had ruled since 1967. He mostly ignored the long-standing socialist and communist complaints about injustice and corruption in Gabon.[30]

Rwanda

The French daily newspaper Le Monde printed newly declassified government memos and diplomatic telegrams revealing Mitterrand's support for Habyariamana's regime on July 6, 2007. The official French policy was to push Habyarimana in sharing power, while stopping Paul Kagamé's FPR's military advance, supported by Uganda.[31] On April 2, 1993, after an agreement between Habyarimana and Kagamé which prepared the August 1993 Arusha Accords, conservative Prime minister Edouard Balladur envisioned sending 1,000 more soldiers, a proposition accepted by Mitterrand.[31] The documents prove that the French government was aware of ethnic cleansings committed by Hutu extremists as soon as February 1993, a year before the assassination of Habyarimana which triggered a full-scale genocide.[31]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Tricolor and crescent: France and the Islamic world by William E. Watson p.1

- ^ The Champions of Change Dr. Allah Bakhsh Malik p.29ff

- ^ Reconquest and crusade in medieval Spain by Joseph F. O'Callaghan p.31

- ^ African glory: the story of vanished Negro civilizations by John Coleman De Graft-Johnson p.121 [1]

- ^ Carter G. Woodson: a historical reader by Carter Godwin Woodson p.43 [2]

- ^ a b African glory: the story of vanished Negro civilizations by John Coleman De Graft-Johnson p.122 [3]

- ^ Canary Islands by Sarah Andrews,Josephine Quintero p.25

- ^ Three years in Constantinople by Charles White p.139

- ^ Three years in Constantinople by Charles White p.147

- ^ Suleiman the Magnificent 1520–1566 Roger Bigelow Merriman p.139

- ^ Suleiman the Magnificent 1520–1566 Roger Bigelow Merriman p.140

- ^ The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II by Fernand Braudel p.920- [4]

- ^ "Francois I, hoping that Morocco would open up to France as easily as Mexico had to Spain, sent a commission, half commercial and half diplomatic, which he confided to one Pierre de Piton. The story of his mission is not without interest" in The conquest of Morocco by Cecil Vivian Usborne, S. Paul & co. ltd., 1936, p.33

- ^ Travels in Morocco, Volume 2 James Richardson p.32

- ^ The International City of Tangier, Stuart, p.38

- ^ Studies in Elizabethan Foreign Trade p.149

- ^ "The narrative really begins in 1619, when the adventurer, Admiral S. John de Razilly, resolved to go to Africa. France had no colony in Morocco; hence, King Louis XIII gave whole-hearted support to de Razilly." in Round table of Franciscan research, Volumes 17–18 Capuchin Seminary of St. Anthony, 1952

- ^ [The chevalier de Montmagny (1601–1657): first governor of New France by Jean-Claude Dubé, Elizabeth Rapley p.111]

- ^ A man of three worlds Mercedes García-Arenal, Gerard Albert Wiegers p.114

- ^ France in the age of Louis XIII and Richelieu by Victor Lucien Tapié p.259

- ^ International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa by Trudy Ring p.303 [5]

- ^ Navies in modern world history Lawrence Sondhaus p.71ff

- ^ Winock, Michel. "De Gaulle and the Algerian Crisis 1958–1962." in Hugh Gough and John Home, eds., De Gaulle and Twentieth Century France (1994) pp 71–82.

- ^ Slavery and colonial rule in French West Africa by Martin A. Klein, p.59 [6]

- ^ Julian Jackson, De Gaulle (2018), pp 490–93, 525, 609–615.

- ^ Patrick Manning, Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880–1995 (1999) pp 137–41, 149–50, 158–62.

- ^ John R. Frears, France in the Giscard Presidency (1981) pp 109–127.

- ^ Christopher Griffin, "French military policy in the Nigerian Civil War, 1967–1970." Small Wars & Insurgencies 26.1 (2015): 114–135.

- ^ "François Mitterrand et l'Afrique: "Il a toujours eu une forme de paternalisme autoritaire"". TV5MONDE (in French). 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ David E. Gardinier, "France and Gabon since 1993: The reshaping of a neo-colonial relationship." Journal of Contemporary African Studies 18.2 (2000): 225–242.

- ^ a b c Génocide rwandais : ce que savait l'Elysée, Le Monde, 2 July 2007 (in French)

Further reading

- Chafer, Tony, and Alexander Keese, eds. Francophone Africa at fifty (Oxford UP, 2015).

- Charbonneau, Bruno. France and the New Imperialism: Security Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa (Routledge 2016).

- Charbonneau, Bruno. "The imperial legacy of international peacebuilding: the case of Francophone Africa." Review of International Studies 40.3 (2014): 607–630. online[dead link]

- Crocker, Chester A. "Military dependence: the colonial legacy in Africa." Journal of Modern African Studies 12.2 (1974): 265–286.

- Erforth, Benedikt. (2020) "Multilateralism as a tool: Exploring French military cooperation in the Sahel." Journal of Strategic Studies

- Gardinier, David E. "France and Gabon since 1993: The reshaping of a neo-colonial relationship." Journal of Contemporary African Studies 18.2 (2000): 225–242.

- Gerits, Frank. "The postcolonial cultural transaction: rethinking the Guinea crisis within the French cultural strategy for Africa, 1958–60." Cold War History (2019): 1–17. onlineonline

- Marina E. Henke (2020) "A tale of three French interventions: Intervention entrepreneurs and institutional intervention choices." Journal of Strategic Studies.

- Johnson, G. Wesley. ed. Double Impact: France and Africa in the Age of Imperialism (1985) online essays by scholars

- Johnson, G. Wesley. France and the Africans, 1944–1960: A Political History. (Greenwood Press, 1985). ISBN 0313233861.

- McNamara, Francis Terry. France in Black Africa (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1989).

- Manning, Patrick. Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880–1995 (2nd ed. 1999)

- Martin, Guy. "The Historical, Economic, and Political Bases of France's African Policy." Journal of modern African studies 23.2 (1985): 189–208.

- Martin, Guy. "France's African policy in transition: disengagement and redeployment." Colección 10.5 (2017): 97–119. online

- Mukonoweshuro, Eliphas G. "French Commercial Interests in Non-Francophone Africa." Africa Quarterly 30.1–2 (1990): 13–26.

- Stefano Recchia & Thierry Tardy (2020) "French military operations in Africa: Reluctant multilateralism," Journal of Strategic Studies.

- Thierry Tardy (2020) "France’s military operations in Africa: Between institutional pragmatism and agnosticism," Journal of Strategic Studies.

- Wood, Sarah L. "How Empires Make Peripheries: 'Overseas France' in Contemporary History." Contemporary European History (2019): 1–12. online[dead link]

- Yates, Douglas A. "France and Africa." in Africa and the World (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018) pp. 95–118. online