Foreign policy of Xi Jinping

The foreign policy of Xi Jinping concerns the policies of the People's Republic of China's Xi Jinping with respect to other nations. Xi became the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012 and became the President of the People's Republic of China in 2013.

Xi has reportedly taken a hard-line on security issues as well as foreign affairs, projecting a more nationalistic and assertive China on the world stage.[1] His political program calls for a China more united and confident of its own value system and political structure.[2] Xi Jinping's "Major Country Diplomacy" (Chinese: 大国外交) doctrine has replaced the earlier Deng Xiaoping era slogan of "keep a low profile" (Chinese: 韬光养晦) and has legitimized a more active role for China on the world stage, particularly with regards to reform of the international order, engaging in open ideological competition with the West, and assuming a greater responsibility for global affairs in accordance with China's rising power and status.[3] Xi has advocated for diplomats to adopt a more assertive style, commonly expressed as Wolf warrior diplomacy.

In setting foreign policy, Xi favors an approach of baseline thinking, in which China explicitly states red line that other countries must not cross. In the Chinese perspective, taking tough positions on these matters reduces strategic uncertainty.

Overview

Xi takes a strong personal interest in foreign affairs.[4]: 14 In his first five years in office, Xi flew over 350,000 miles, visited five continents, and gave over one hundred speeches to foreign audiences.[4]: 14–15 In doing so, he became the first Chinese leader to outpace his American presidential counterparts in foreign travel.[4]: 15 Xi's extensive schedule of phone and video foreign meetings as part of his "cloud diplomacy" (云外交) received prominent attention in Chinese media, similar to in-person foreign visits.[4]: 15

Xi has overseen a shift towards a Chinese foreign policy which, as contrasted with the approaches of Chinese leaders since Deng Xiaoping, is more assertive in acting proactively rather than reacting, and more willing to forcefully assert national interests rather than compromise them.[4]: 78 Xi states that the "primary theme of China's foreign policy should be the striving for achievements, moving forward along with time changes, and acting more proactively."[4]: 85 Xi calls on diplomats to demonstrate a fighting spirit, which has been expressed in the form of wolf warrior diplomacy.[4]: 79

During the Xi Jinping era, the Community of Shared Future for Mankind has become China's most important foreign relations formulation.[5]: 6

Xi advocates "baseline thinking" in China's foreign policy: setting explicit red lines that other countries must not cross.[4]: 86 In the Chinese perspective, these tough stances on baseline issues reduce strategic uncertainty, preventing other nations from misjudging China's positions or underestimating China's resolve in asserting what it perceives to be in its national interest.[4]: 86

Before 2017, Xi stated that China should participate in forming a new global order.[4]: 240 This position changed in 2017, when Xi articulated the "Two Guidances": (1) China should guide the global community in building a more just and reasonable world order, and (2) that China should guide the global community in safeguarding international security.[4]: 240

During the COVID-19 pandemic, China engaged in mask diplomacy, a practice facilitated by its early success in responding to the pandemic.[4]: 90 Chinese ownership of much of the global medical supply chain enhanced its ability to send doctors and medical equipment to suffering countries.[4]: 90 China soon followed its mask diplomacy with vaccine diplomacy.[4]: 90 China's infection rates were sufficiently low that it could send vaccines abroad without domestic objections.[4]: 90 Academic Suisheng Zhao writes that "[j]ust by showing up and helping plug the colossal gaps in the global supply, China gained ground."[4]: 90

In the Xi era, China takes the position that unilateral economic restrictions and trade discrimination are impermissible measures for countries to use in achieving foreign policy goals and has positioned itself generally as a proponent of global free trade.[6]: 16 In his January 2021 speech during the Davos Economic Forum, Xi called for abandonment of deliberate decoupling and the use of sanctions, stating that maintaining a commitment to diplomacy and a multilateral trade regime were important.[6]: 16–17

During the Xi Jinping administration, China seeks to shape international norms and rules in emerging policy areas where China has an advantage as an early participant.[7]: 188 Xi describes such areas as "new frontiers," and they include policy areas such as space, deep sea, polar regions, the Internet, nuclear safety, anticorruption, and climate change.[7]: 188

In foreign policy announcements, Xi sometimes refers to "Great Changes Unseen in a Century".[8]: 34 The phrase refers to the perceived decline of United States power both domestically and internationally, as well as the broader fragmentation of Western powers.[8]: 34

Taiwan (Republic of China)

In 2015, Xi met with Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou, which marked the first time the political leaders of both sides of the Taiwan Strait met since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950.[9] Xi said that China and Taiwan are "one family" that cannot be pulled apart.[10] However, the relations started deteriorating after Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) won the presidential elections in 2016.[11]

In the 19th Party Congress held in 2017, Xi reaffirmed six of the nine principles that had been affirmed continuously since the 16th Party Congress in 2002, with the notable exception of "Placing hopes on the Taiwan people as a force to help bring about unification."[12] According to the Brookings Institution, Xi used stronger language on potential Taiwan independence than his predecessors towards previous DPP governments in Taiwan.[12] He said that "we will never allow any person, any organisation, or any political party to split any part of the Chinese territory from China at any time at any form."[12] In March 2018, Xi said that Taiwan would face the "punishment of history" for any attempts at separatism.[13]

In January 2019, Xi Jinping called on Taiwan to reject its formal independence from China, saying: "We make no promise to renounce the use of force and reserve the option of taking all necessary means." Those options, he said, could be used against "external interference." Xi also said that they "are willing to create broad space for peaceful reunification, but will leave no room for any form of separatist activities."[14][15] President Tsai responded to the speech by saying Taiwan would not accept a one country, two systems arrangement with the mainland, while stressing the need for all cross-strait negotiations to be on a government-to-government basis.[16]

Xi states that reunification with Taiwan should occur peacefully because that is "most in line with the overall interest of the Chinese nation, including Taiwan compatriots."[17] In a speech at the 100th Anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi stated:[18]

Resolving the Taiwan question and realizing China’s complete reunification is a historic mission and an unshakable commitment of the Communist Party of China. It is also a shared aspiration of all the sons and daughters of the Chinese nation. We will uphold the one-China principle and the 1992 Consensus, and advance peaceful national reunification. All of us, compatriots on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, must come together and move forward in unison. We must take resolute action to utterly defeat any attempt toward “Taiwan independence,” and work together to create a bright future for national rejuvenation. No one should underestimate the resolve, the will, and the ability of the Chinese people to defend their national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Xi has also said that unification under a "one country, two systems" approach would be appropriate.[17] The American think tank Council on Foreign Relations described Xi's position on Taiwan as continuing consistent with China's 1979 shift from "liberation" of Taiwan to "peaceful unification" with Taiwan.[18]

In 2022, after the Chinese military exercises around Taiwan, the PRC published a white paper called "The Taiwan Question and China's Reunification in the New Era," which was the first white paper regards to Taiwan since 2000.[19] The paper urged Taiwan to become a special administrative region of the PRC under the one country two systems formula,[19] and said that "a small number of countries, the U.S. foremost amongst them" are "using Taiwan to contain China."[20] Notably, the new white paper excluded a part that previously said the PRC would not send troops or officials to Taiwan after unification.[20]

Africa

During Xi's administration, China has maintained cordial relationships with each Africa government except Eswatini, which recognizes Taiwan but not the PRC.[5] Xi's diplomatic rhetoric links the China-Africa Community of Shared Future to the concept of the Chinese Dream.[5]: 21 Although Xi has generally prioritized relations between the Communist Party of China and political parties in the Global South, Xi has especially prioritized such party-to-party relations in Africa.[5]: 85

At the 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, Xi emphasized the "Five Nos" which guide its foreign policy in dealing with African countries and other developing countries: (1) non-interference in other countries' pursuit of development paths suitable to their national conditions, (2) non-interference in domestic affairs, (3) not imposing China's will on others, (4) not attaching political conditions to foreign aid, and (5) not seeking political self-interest in investment and financing.[21]: 108–109

Under Xi, China has cut back lending to Africa after fears that African countries couldn't repay their debts to China.[22] Xi has also promised that China would write off debts of some African countries.[23] In November 2021, Xi promised African nations 1 billion doses of China's COVID-19 vaccines, which was in addition to the 200 million already supplied before. This has been said to be part of China's vaccine diplomacy.[24]

Americas

United States

Xi has called China–United States relations in the contemporary world a "new type of great-power relations", a phrase the Obama administration had been reluctant to embrace.[25] Under his administration the Strategic and Economic Dialogue that began under Hu Jintao has continued. On China–U.S. relations, Xi said, "If [China and the United States] are in confrontation, it would surely spell disaster for both countries".[26] Xi has described relations between China and United States in terms of the Thucydides Trap, a term first used by political scientist Graham Allison, meaning that in a clash between two great powers that could otherwise cooperate for the benefit of humanity, all would lose.[27]: 54

'The U.S. has been critical of Chinese actions in the South China Sea.[25] In 2014, Chinese hackers compromised the computer system of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management,[28] resulting in the theft of approximately 22 million personnel records handled by the office.[29]

Xi has indirectly spoken out critically on the U.S. "strategic pivot" to Asia.[30] Addressing a regional conference in Shanghai on 21 May 2014, he called on Asian countries to unite and forge a way together, rather than get involved with third party powers, seen as a reference to the United States. "Matters in Asia ultimately must be taken care of by Asians. Asia's problems ultimately must be resolved by Asians and Asia's security ultimately must be protected by Asians", he told the conference.[31]

In spite of what seemed to be a tumultuous start to Xi Jinping's leadership vis-à-vis the United States, on 13 May 2017 Xi said at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing: "We should foster a new type of international relations featuring 'win-win cooperation', and we should forge a partnership of dialogue with no confrontation, and a partnership of friendship rather than alliance. All countries should respect each other's sovereignty, dignity and territorial integrity; respect each other's development path and its social systems, and respect each other's core interests and major concerns... What we hope to create is a big family of harmonious coexistence."[32]

Relations with the U.S. soured after Donald Trump became president in 2017.[33] Since 2018, U.S. and China have been engaged in an escalating trade war.[34] In 2020, the relations further deteriorated due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[35] In 2021, Xi has called the U.S. the biggest threat to China's development, saying that "the biggest source of chaos in the present-day world is the United States."[36] Xi has also scrapped a previous policy in which China did not challenge the U.S. in most instances, while Chinese officials said that they now see China as an "equal" to the U.S.[37] On 6 March 2023, during a speech to the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), Xi said that "Western countries—led by the U.S.—have implemented all-round containment, encirclement and suppression" against China, which he said brought "unprecedentedly severe challenges to our country's development."[38]

Asia

India

Relations between China and India had ups and downs under Xi, later deteriorating due to various factors. In 2013, the two countries had a standoff in Depsang for three weeks, which ended with no border change.[39] In 2017, the two countries again had a standoff over a Chinese construction of a road in Doklam, a territory both claimed by Bhutan, India's ally, and China,[40] though by 28 August, both countries mutually disengaged.[41] The most serious crisis in the relationship came when the two countries had a deadly clash in 2020 at the Line of Actual Control, leaving some soldiers dead.[42][43] The clashes created a serious deterioration in relations, with China seizing 2,000 km2 territory that India controlled.[44][45]

Iran

On 4 June 2019, Xi told the Russian news agency TASS that he was "worried" about the current tensions between the U.S. and Iran.[46] He later told his Iranian counterpart Hassan Rouhani during an SCO meeting that China would promote ties with Iran regardless of developments from the Gulf of Oman incident.[47]

Japan

China–Japan relations have initially soured under Xi's administration; the most thorny issue between the two countries remains the dispute over the Senkaku islands, which China calls Diaoyu. In response to Japan's continued robust stance on the issue, China declared an Air Defense Identification Zone in November 2013.[48] However, the relations later started to improve, with Xi being invited to visit in 2020,[49] though the trip was later delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[50] In August 2022, Kyodo News reported that Xi personally decided to let ballistic missiles land within Japan's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) during the military exercises held around Taiwan, to send a warning to Japan.[51]

Korea

Under Xi, China initially took a more critical stance on North Korea due to its nuclear tests.[52] However, starting in 2018, the relations started to improve due to meetings between Xi and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.[53] Xi has also supported denuclearization of North Korea,[54] and has voiced support for economic reforms in the country.[55] At the G20 meeting in Japan, Xi called for a "timely easing" of sanctions imposed on North Korea.[56] After the 20th CCP National Congress in 2022, Rodong Sinmun, official newspaper of the ruling Workers' Party of Korea, wrote a long editorial praising Xi, titling both Kim and Xi Suryong (수령), a title historically reserved for North Korea's founder Kim Il Sung.[57]

Xi has initially improved relationships with South Korea,[58] and the two countries signed a free-trade agreement in December 2015.[59] Starting in 2017, China's relationship with South Korea soured over the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD), a missile defence system, purchase of the latter. which China sees as a threat but which South Korea says is a defence measure against North Korea.[60] Ultimately, South Korea halted the purchase of the THAAD after China imposed unofficial sanctions.[61] China's relations with South Korea improved again under president Moon Jae-in.[62]

Middle East

While China has historically been wary of getting closer to the Middle East countries, Xi has changed this approach.[63] China has grown closer to both Iran and Saudi Arabia under Xi.[63] During a visit to Iran in 2016, Xi proposed a large cooperation program with Iran,[64] a deal that was later signed in 2021.[65] China has also sold ballistic missiles to Saudi Arabia and is helping build 7,000 schools in Iraq.[63] In 2013, Xi proposed a peace deal between Israel and Palestine that entails a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders.[66] Turkey, with whom relations were long strained over Uyghurs, has also grown closer to China.[67] On 10 March 2023, Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to restore diplomatic ties cut in 2016 after a deal brokered between the two countries by China following secret talks in Beijing.[68]

Southeast Asia

Since Xi came to power, China has been rapidly building and militarizing islands in the South China Sea, a decision Study Times of the Central Party School said was personally taken by Xi.[69] In April 2015, new satellite imagery revealed that China was rapidly constructing an airfield on Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands of the South China Sea.[70] In November 2014, in a major policy address, Xi called for a decrease in the use of force, preferring dialogue and consultation to solve the current issues plaguing the relationship between China and its South East Asian neighbors.[71]

Vietnam

On December 12, 2023, Vietnam and China announced 36 cooperation agreements during a visit by Xi to Vietnam.[72] The agreements addressed a variety of issues, including cross-border rail development, digital infrastructure, and establishing joint patrols in the Gulf of Tonkin and a hotline to handle South China Sea fishing incidents.[72] The two countries also issued a joint statement to support building a community of shared future for humankind.[72]

Europe

European Union

China's efforts under Xi has been for the European Union (EU) to stay in a neutral position in their contest with the U.S.[73] China and the EU announced the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) in 2020, although the deal was later frozen due to mutual sanctions over Xinjiang.[74] Xi has supported calls for EU to achieve "strategic autonomy,"[75] and has also called on the EU to view China "independently."[76]

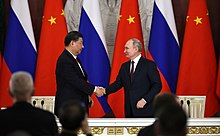

Russia

Xi has cultivated stronger relations with Russia, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine crisis of 2014. He seems to have developed a strong personal relationship with president Vladimir Putin. Both are viewed as strong leaders with a nationalist orientation who are not afraid to assert themselves against Western interests.[77] Xi attended the opening ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Under Xi, China signed a $400 billion gas deal with Russia; China has also become Russia's largest trading partner.[77]

Xi and Putin met on 4 February 2022 during the run up to the 2022 Beijing Olympics during the massive Russian build-up of force on the Ukrainian border, with the two expressing that the two countries are nearly united in their anti-US alignment and that both nations shared "no limits" to their commitments.[78][79] U.S. officials said that China had asked Russia to wait for the invasion of Ukraine until after the Beijing Olympics ended on 20 February.[79] In April 2022, Xi Jinping expressed opposition to sanctions against Russia.[80] On 15 June 2022, Xi Jinping reasserted China's support for Russia on issues of sovereignty and security.[81] However, Xi also said China is committed to respecting "the territorial integrity of all countries,"[82] and said China was "pained to see the flames of war reignited in Europe."[83] China has additionally kept a distance from Russia's actions, instead putting itself as a neutral party.[79] In February 2023, China released a 12-point peace plan to "settle the acute crisis in Ukraine"; the plan was praised by Putin but criticized by the U.S. and European countries.[84]

During the war Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy has given a nuanced take to China,[85] saying that the country has the economic leverage to pressure Putin to end the war, adding "I'm sure that without the Chinese market for the Russian Federation, Russia would be feeling complete economic isolation. That's something that China can do – to limit the trade [with Russia] until the war is over." In August 2022, Zelenskyy said that since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Xi Jinping did not respond to his requests for direct talks with him.[86] He additionally said that while he would like China to take a different approach to the war in Ukraine, he also wanted the relationship to improve every year and said that China and Ukraine shared similar values.[87] On 26 April 2023, Zelenskyy and Xi held their first phone call since the start of the war.[88]

See also

References

- ^ Kuhn, Robert Lawrence (6 June 2013). "Xi Jinping, a nationalist and a reformer". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Meng, Angela (6 September 2014). "Xi Jinping rules out Western-style political reform for China". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Smith, Stephen N. (16 February 2021). "China's "Major Country Diplomacy"". Foreign Policy Analysis. doi:10.1093/fpa/orab002. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Zhao, Suisheng (2023). The Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign Policy. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. doi:10.1515/9781503634152. ISBN 978-1-5036-3088-8. OCLC 1331741429.

- ^ a b c d Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (2023). China's Relations with Africa: a New Era of Strategic Engagement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0.

- ^ a b Korolev, Alexander S. (2023). "Political and Economic Security in Multipolar Eurasia". China and Eurasian Powers in a Multipolar World Order 2.0: Security, Diplomacy, Economy and Cyberspace. Mher Sahakyan. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-35258-7. OCLC 1353290533.

- ^ a b Tsang, Steve; Cheung, Olivia (2024). The Political Thought of Xi Jinping. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197689363.

- ^ a b Curtis, Simon; Klaus, Ian (2024). The Belt and Road City: Geopolitics, Urbanization, and China's Search for a New International Order. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300266900.

- ^ Perlez, Jane; Ramzy, Austin (4 November 2015). "China, Taiwan and a Meeting After 66 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "One-minute handshake marks historic meeting between Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-jeou". The Straits Times. 7 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Huang, Kristin (15 June 2021). "Timeline: Taiwan's relations with mainland China under Tsai Ing-wen". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Bush, Richard C. (19 October 2017). "What Xi Jinping said about Taiwan at the 19th Party Congress". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ Wen, Philip; Qiu, Stella (20 March 2018). "Xi Jinping warns Taiwan it will face 'punishment of history' for separatism". The Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (2 January 2019). "'All necessary means': Xi Jinping reserves right to use force against Taiwan". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Griffiths, James (2 January 2019). "Xi warns Taiwan independence is 'a dead end'". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Lee, Yimou (2 January 2019). "Taiwan president defiant after China calls for reunification". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ a b "China-Taiwan tensions: Xi Jinping says 'reunification' must be fulfilled - BBC News". BBC News. 2022-07-25. Archived from the original on 2022-07-25. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ a b "What Xi Jinping's Major Speech Means For Taiwan". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ a b Millson, Alex (10 August 2022). "China's First White Paper on Taiwan Since Xi Came to Power — In Full". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ a b Falconer, Rebecca (11 August 2022). "New Beijing policy removes pledge not to send troops to Taiwan if it takes control of island". Axios. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Meng, Wenting (2024). Developmental Peace: Theorizing China's Approach to International Peacebuilding. Ibidem. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9783838219073.

- ^ Hille, Kathrin; Pilling, David (11 January 2022). "China applies brakes to Africa lending". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ He, Laura (19 June 2020). "China is promising to write off some loans to Africa. It may just be a drop in the ocean". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "China's Xi promises 1bn COVID-19 vaccine doses to Africa". Al Jazeera. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ a b Hiroyuki, Akita (22 July 2014). "A new kind of 'great power relationship'? No thanks, Obama subtly tells China". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Ng, Teddy; Kwong, Man-ki (9 July 2014). "President Xi Jinping warns of disaster if Sino-US relations sour". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Gnerre, Orazio Maria (2023). "Strengthening of the Sino-Russian Partnership". China and Eurasian Powers in a Multipolar World Order 2.0: Security, Diplomacy, Economy and Cyberspace. Mher Sahakyan. New York. ISBN 978-1-003-35258-7. OCLC 1353290533.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Perez, Evan (24 August 2017). "FBI arrests Chinese national connected to malware used in OPM data breach". CNN. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Nakashima, Ellen (9 July 2015). "Hacks of OPM databases compromised 22.1 million people, federal authorities say". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Blanchard, Ben (3 July 2014). "With one eye on Washington, China plots its own Asia 'pivot'". Reuters. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Asian nations should avoid military ties with third party powers, says China's Xi". China National News. 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Perlez, Jane; Bradsher, Keith (2017-05-14). "Xi Jinping Positions China at Center of New Economic Order". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ Brown, Adrian (12 May 2019). "China-US trade war: Sino-American ties being torn down brick by brick". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (5 July 2018). "Trump's Trade War With China Is Officially Underway". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ "Relations between China and America are infected with coronavirus". The Economist. 26 March 2020. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (3 March 2021). "'The East Is Rising': Xi Maps Out China's Post-Covid Ascent". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Wei, Lingling; Davis, Bob (12 April 2021). "China's Message to America: We're an Equal Now". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han; Zhai, Keith; Areddy, James T. (6 March 2023). "China's Xi Jinping Takes Rare Direct Aim at U.S. in Speech". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ "India says China agrees retreat to de facto border in faceoff deal". Reuters. 6 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "China says India violates 1890 agreement in border stand-off". Reuters. 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey; Hernández, Javier C. (28 August 2017). "China and India Agree to Ease Tensions in Border Dispute". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Janjua, Haroon (10 May 2020). "Chinese and Indian troops injured in border brawl". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Indian and Chinese soldiers injured in cross-border fistfight, says Delhi". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 11 May 2020. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Siddiqui, Imran Ahmed (2023-06-16). "'Subjugation and surrender': Military veterans slam Modi government's continuing silence on Galwan". Telegraph India.

- ^ Myers, Steven Lee; Abi-Habib, Maria; Gettleman, Jeffrey (17 June 2020). "In China-India Clash, Two Nationalist Leaders With Little Room to Give". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "Xi worried as 'extreme' US pressure on Iran raises tensions". Al Jazeera. 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Martina, Michael (June 14, 2019). "Xi says China will promote steady ties with Iran". Reuters. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ Osawa, Jun (17 December 2013). "China's ADIZ over the East China Sea: A "Great Wall in the Sky"?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Albert, Eleanor (16 March 2019). "China and Japan's Rapprochement Continues – For Now". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Tim (28 February 2021). "China's Xi will not make a state visit to Japan this year -Sankei". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Xi let missiles fall in Japan EEZ during Taiwan drills: sources". Kyodo News. 11 August 2022. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Li, Cheng (26 September 2014). "A New Type of Major Power Relationship?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Shi, Jiangtao; Chan, Minnie; Zheng, Sarah (27 March 2018). "Kim's visit evidence China, North Korea remain allies, analysts say". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Song, Jung-a; Shepherd, Christian (21 June 2019). "Xi Jinping vows active role in Korea denuclearisation talks". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Bodeen, Christopher (20 April 2021). "China's Xi pushes economic reform at North Korea summit". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Lee, Jeong-ho (2 July 2019). "Xi calls for 'timely' easing of North Korea sanctions after Trump-Kim meeting". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Isozaki, Atsuhito (23 December 2022). "China Relations Key to Situation in North Korea". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Li, Cheng (26 September 2014). "A New Type of Major Power Relationship?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Kim, Bo-eun (26 July 2022). "China, South Korea renew service sector talks, opening up a 'win-win for both economies'". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Huang, Cary (2 April 2017). "Why China's economic jabs at South Korea are self-defeating". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Kim, Christine; Blanchard, Ben (31 October 2017). "China, South Korea agree to mend ties after THAAD standoff". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Park, Chan-kyong (26 January 2021). "Xi charms Moon as China and US compete for an ally in South Korea". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Vohra, Anchal (1 February 2022). "Xi Jinping Has Transformed China's Middle East Policy". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz; Myers, Steven Lee (11 July 2020). "Defying U.S., China and Iran Near Trade and Military Partnership". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Iran and China sign 25-year cooperation agreement". Reuters. 27 March 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Figueroa, William (25 May 2021). "Can China's Israel-Palestine Peace Plan Work?". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Tepe, Sultan; Alemdaroglu, Ayca (16 September 2020). "Erdogan Is Turning Turkey Into a Chinese Client State". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Kalin, Stephen; Faucon, Benoit (10 March 2023). "Saudi Arabia, Iran Restore Relations in Deal Brokered by China". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Journal of Current Chinese Affairs" (PDF). giga-hamburg.de. May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ "China building runway in disputed South China Sea island". BBC News. 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Miller, Matthew (7 September 2019). "China's Xi tones down foreign policy rhetoric". CNBC. Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Guarascio, Francesco; Vu, Khanh; Nguyen, Phuong (December 12, 2023). "Vietnam Boosts China Ties as 'Bamboo Diplomacy' Follows US Upgrade". Reuters. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Buckley, Chris; Bradsher, Keith (15 April 2022). "Faced With a Changed Europe, China Sticks to an Old Script". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Miller, Michael E. "China says Macron and Merkel support reviving E.U.-China investment pact. Not so fast". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Wang, Amber (14 December 2021). "Dangers for China in the EU drive for strategic autonomy: analyst". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "China's Xi calls on EU to view China 'independently' -state media". Reuters. 1 April 2022. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b Baker, Peter (8 November 2014). "As Russia Draws Closer to China, U.S. Faces a New Challenge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Chao Deng; Ann M. Simmons; Evan Gershkovich; William Mauldin (4 February 2022). "Putin, Xi Aim Russia-China Partnership Against U.S." The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Buckley, Chris; Myers, Steven Lee (7 March 2022). "'No Wavering': After Turning to Putin, Xi Faces Hard Wartime Choices for China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Ng, Teddy (2 April 2022). "Chinese President Xi Jinping warns it could take decades to repair economic damage caused by Ukraine crisis". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Lau, Stuart (15 June 2022). "China's Xi gives most direct backing to Putin since invasion". Politico. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "China's Xi Says International Disputes Should be Resolved Via Dialogue, Not Sanctions". Voice of America. 21 April 2022. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "China's Xi: Beijing supports peace talks between Russia, Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 9 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Putin to Xi: We will discuss your plan to end the war in Ukraine". BBC News. 22 March 2023. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Santora, Marc (2022-08-03). "On China, the normally forceful Zelensky offers a nuanced view". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ "Zelenskyy urges China's Xi to help end Russia's war in Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 4 August 2022. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Chew, Amy (2022-08-04). "Exclusive: Zelensky seeks talks with China's Xi to help end Russia's invasion of Ukraine". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ "Xi Speaks With Zelenskiy for First Time Since Russia's War in Ukraine Began". Bloomberg News. 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.