Art of the Crusades

Crusader art or the art of the Crusades, meaning primarily the art produced in Middle Eastern areas under Crusader control, spanned two artistic periods in Europe, the Romanesque and the Gothic, but in the Crusader kingdoms of the Levant the Gothic style barely appeared. The military crusaders themselves were mostly interested in artistic and development matters, or sophisticated in their taste, and much of their art was destroyed in the loss of their kingdoms so that only a few pieces survive today. Probably their most notable and influential artistic achievement was the Crusader castles, many of which achieve a stark, massive beauty. They developed the Byzantine methods of city-fortification for stand-alone castles far larger than any constructed before, either locally or in Europe.

The crusaders encountered a long and rich artistic tradition in the lands they conquered at the end of the 11th century and the beginning of the 12th. Byzantine and Islamic art (that of both the Arabs and the Turks) were the dominant styles in the Crusader states, although there were also the styles of the indigenous Syrians and Armenians. These indigenous styles were incorporated into styles brought by the crusaders from Europe, which were themselves highly varied, stemming from France, Italy, Germany, England, and elsewhere. On the whole the Eastern Christian styles were more significant influences than Islamic art; the artists working in the Crusader lands are assumed to have had the same variety of backgrounds. Many art historians attempt to guess the backgrounds, in terms of ethnicity, place of birth and training, of the artists involved with particular works, an effort treated with caution by Kurt Weitzmann, Doula Mouriki, and Jaroslav Folda, author of the most recent detailed survey.[1]

Crusader art in the Levant, like the history of the Crusader kingdoms in general, falls clearly into two, or three, periods. The first begins with the First Crusade which culminated in 1099 with the bloody taking of Jerusalem and the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other states to the north. The following decades were turbulent but artistically productive, until the catastrophe of 1187 saw the Crusader defeat at the Battle of Hattin and the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin. In the second period the Kingdom of Jerusalem was now hugely reduced in size to control only a few coastal towns and the areas around them, which were gradually whittled away by the Muslims until the final Siege of Acre (1291) ended Crusader presence in the Levant. However the kingdom still controlled Cyprus, taken from the Byzantine Empire, and the House of Lusignan continued to rule there, and later the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, until respectively 1489 and the late 14th century, representing the third period of Crusader art, not counted as such by all sources; in Cyprus the Gothic style is often found.[2]

There is a further sense of "Crusader art" to cover the art produced in the Latin Empire that usurped much of the Byzantine Empire, ruled by the Crusaders between the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade and 1261. Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai was also a centre during this time, and perhaps later. This art had a larger impact in Europe, to which many artists probably returned after the collapse of the regime, influencing Italo-Byzantine painting there. The crusades were also important as a subject in Western art, mainly in illuminated luxury versions of the many histories that were popular reading with Western elites.

Illuminated manuscripts

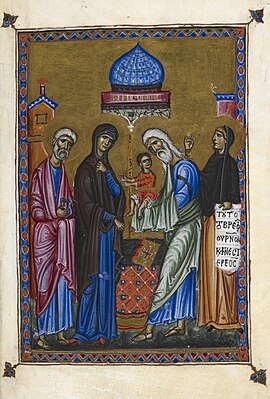

An example of the mixture of different styles is the Melisende Psalter, an illuminated manuscript produced in the mid-12th century, perhaps for Queen Melisende of Jerusalem. It reflects her European and Armenian heritage, and is also influenced by Byzantine and Islamic techniques. The Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt was an important centre where a school of manuscript and icon painting that blended European and local influences emerged. Fortunately it has also been a very secure home for its collection of icons (but not manuscripts in Latin, all of which were later destroyed, apparently under Russian influence), so a good number have survived there. Artists who can be identified on stylistic grounds as originating in France and Italy (Venice and Apulia) worked there, producing work mixing Byzantine and Western conventions, but usually with lettering in Greek. This was possible because by a quirk of Orthodox history the church there was in communion with both the Catholic and the other Orthodox churches, and so the normal sectarian divides that separated the crusaders from even the local Christians did not operate.

There was also a scriptorium in Acre which produced many well known manuscripts such as missals and the Arsenal Bible,[3] especially noted for commissions by King Louis IX of France.[4] The frontispiece to Proverbs 1 in the Arsenal Bible shows Solomon wearing the traditional insignia and clothing of a Byzantine emperor, in a mixture of the Gothic and Franco-Byzantine Crusader styles, and also shows French architecture.[4] Most of the significant surviving illuminated manuscripts were produced in the 13th century, about half in the last forty years of the Latin kingdom; to what extent this is an accident of survival is unclear.[4]

Mosaics, frescoes and panel paintings

An example of the mixture of styles is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the renovation and rebuilding of which was completed in 1149; however only fragments of the large programme of mosaics now survive. This was until the loss of Jerusalem in 1187 the institution with the main Crusader scriptorium, from which six manuscripts survive, made in a mixture of royal and church commissions.[5] Most of the significant surviving illuminated manuscripts were produced in the 13th century, about half in the last forty years of the Latin kingdom; to what extent this is an accident of survival is unclear.[6] Some icons in wall painting and mosaic survive from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.[5] The Hospitaller church at Abu Ghosh, apparently then regarded as the biblical Emmaus, was abandoned in 1187 but has good remains of frescos. Some wall paintings and mosaic sections survive from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem,[5] and there are frescoes at Lagoudhera on Cyprus.[3]

Sculpture

Figurative monumental sculpture in relief was, some earlier Armenian work apart, not part of local Christian traditions, so the Romanesque sculpture of Europe, especially France, was much the largest influence. Discussion of the varied styles by art historians typically involves only various areas in Europe, mostly in France. Many elements were re-used in later buildings, and have now re-appeared, often badly damaged. Original work has survived at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, whose carved lintels are now in the Rockefeller Museum in the city, and was removed from the destroyed Church of Santa Maria Latina nearby.

Another major pilgrimage basilica, the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth, was just nearing the completion of a major rebuilding in 1187. Saladin in fact left the Christians in place and does not seem to have damaged the building. However the church was seriously damaged in the next major upheaval in the area, the invasion in 1267 by the Mamluk ruler Baybars, and the sculptures remaining from the church all suffered. In 1908 five extra capitals were excavated, having, it is presumed, been buried in 1187 soon after they were made but before they were put in place, when news of Saladin's approach reached the town. These are in excellent condition, and some of the most famous sculptures of the Crusader period.[7]

The situation is rather different with decorative sculpture, where local influence is much stronger. The beautifully carved and complex decoration on the arches and cornices over the doors into the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is unlike anything in France from this period and reflects local development of Syrian late Roman styles; some parts are probably re-used Roman material. The neighbouring capitals, "based on Justinianic models, are probably the work of local Christian sculptors working for the Latins".[8]

The end of Crusader art

After the rapid collapse of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1187, which must have destroyed a great part of the artwork the crusaders produced,[9] they were mostly confined to a few cities on the Mediterranean coast until Acre was conquered in 1291. Their artistic output did not cease during the 13th century, and shows further influences from the art of the Mamluks and Mongols.

In Cyprus, the Lusignan kingdom continued to produce work, including the Gothic cathedrals of Famagusta (Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque) and Nicosia (Haydarpasha Mosque/Saint Catherine and Selimiye Mosque/Saint Sophia Cathedral), all later used as mosques and relatively well-preserved (minus their figurative sculpture).

Gallery

-

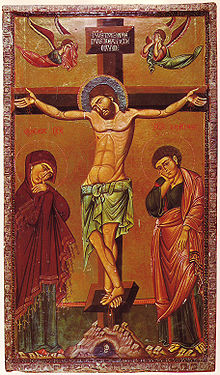

Latin Empire damaged icon, from a Greek church. The central figure of St George is in painted relief, and clearly Latin in style and clothing

-

Several levels of architectural decoration over the doors of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

-

The Holy Sepulchre lintels, still in place in 1856.

-

Holy Sepulchre entrance capitals

-

The main front of the Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque, once Saint Nicholas' Cathedral, Famagusta, Cyprus (note minaret added top left)

-

Gothic arches of Bellapais Abbey in Cyprus

-

Kolossi Castle near Limassol, Cyprus

Influences on Europe

There was also crusade-related art produced back in Europe, from the many illuminated crusade chronicles such as the Old French translation of William of Tyre, to architecture such as the round churches built by the Knights Templar in the style of the Holy Sepulchre, and the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris built to accommodate relics brought back from the East. Luxurious printed textiles began to be produced in Europe at around the end of the Crusades, and may well have been another influence. In general, it is often not possible to say with certainty whether influences or new types of objects arriving in Europe at this period did so via Islamic Spain, the Byzantine world, or the Crusader states. Historians tend to discount the importance of the Crusader States in this regard, despite the very well developed Italian trading networks there. European castle-building was certainly decisively influenced by the crusaders.

See also

Notes

- ^ Folda, I, 13, quoting Weitzmann; I, 17–18, quoting Mouriki; Hunt, Lucy-Anne (1991). "Art and Colonialism: The Mosaics of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (1169) and the Problem of "Crusader" Art". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 45: 69–85. doi:10.2307/1291693. JSTOR 1291693.

- ^ Folda restricts himself to the art of the "Holy Land" or "Syria-Palestine", Folda, I, 19-20

- ^ a b Weitzmann, Kurt (1966). "Icon Painting in the Crusader Kingdom". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 20: 49–83. doi:10.2307/1291242. JSTOR 1291242.

- ^ a b c Jaroslav., Folda (2008). Crusader art : the art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1099-1291. Aldershot: Lund Humphries. ISBN 9780853319955. OCLC 229033386.

- ^ a b c Folda, I, 28

- ^ Folda, I, 13

- ^ Folda, I, 27-28

- ^ Setton and Hazard, 270

- ^ Discussed in detail at Folda, I, 23-28

References

- Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art in the Holy Land: From the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre, 1187–1291, Cambridge University Press, 2005. (ISBN 9780521835831)

Further reading

- Evans, Helen C. & Wixom, William D., The glory of Byzantium: art and culture of the Middle Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261, pp. 389, 1997, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780810965072; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art in the Twelfth Century, B.A.R., 1982.

- Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art: The Art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1099–1291. Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2008. (ISBN 9780853319955)

- Kühnel, Bianca. Crusader Art of the Twelfth Century: A Geographical, an Historical, or an Art Historical Notion?, Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1994.

- Weiss, Daniel H. Art and Crusade in the Age of Saint Louis, Cambridge University Press, 1998. (ISBN 9780521621304)