Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery | |

Crown Hill Cemetery Gateway in 2023 | |

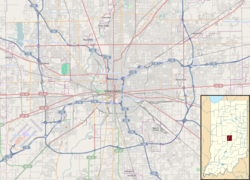

| Location | 3402 Boulevard Place Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°49′13″N 86°10′14″W / 39.82028°N 86.17056°W |

| Area | 555 acres (225 ha) |

| Built | 1885 |

| Architect | D.A. Bohlen; Adolph Scherrer |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000036 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | February 28, 1973 |

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high point overlooking Indianapolis. It is approximately 2.8 miles (4.5 km) northwest of the city's center. Crown Hill was dedicated on June 1, 1864, and encompasses 555 acres (225 ha), making it the third largest non-governmental cemetery in the United States. Its grounds are based on the landscape designs of Pittsburgh landscape architect and cemetery superintendent John Chislett Sr and Prussian horticulturalist Adolph Strauch. In 1866, the U.S. government authorized a U.S. National Cemetery for Indianapolis. The 1.4-acre (0.57 ha) Crown Hill National Cemetery is located in Sections 9 and 10.

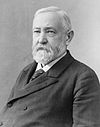

Crown Hill contains 25 miles (40 km) of paved road, over 150 species of trees and plants, over 225,000 graves, and services roughly 1,500 burials per year.[citation needed] Crown Hill is the final resting place for individuals from all walks of life, from political and civic leaders to ordinary citizens, infamous criminals, and unknowns. Benjamin Harrison, 23rd president of the United States, and Vice Presidents Charles W. Fairbanks, Thomas A. Hendricks, and Thomas R. Marshall are buried at Crown Hill. Infamous bank robber and "Public Enemy #1" John Dillinger is another internee. The gravesite of Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley overlooks the city from "The Crown".

Many of the cemetery's mausoleums, monuments, memorials, and structures were designed by architects, landscape designers, and sculptors such as Diedrich A. Bohlen, George Kessler, Rudolf Schwarz, Adolph Scherrer, and the architectural firms of D. A. Bolen and Son and Vonnegut and Bohn, among others. Works by contemporary sculptors include David L. Rodgers, Michael B. Wilson, and Eric Nordgulen.

The cemetery's administrative offices, mortuary, and crematorium are located at 38th Street and Clarendon Road on the cemetery's north grounds. Crown Hill's Waiting Station, built in 1885 at its east entrance on 34th Street and Boulevard Place, serves as a meeting place for tours and programs. The Crown Hill Heritage Foundation, a nonprofit corporation established in 1984, raises funds to preserve the cemetery's historic buildings and grounds. Crown Hill Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 28, 1973.

History

Crown Hill was not Indianapolis's first major cemetery. Alexander Ralston included a cemetery site in his 1821 plan of Indianapolis at the south end of Kentucky Avenue, where it intersects South and West Streets.[2] Prior to the establishment of Crown Hill Cemetery in 1863, the city's main cemetery was expanded in the 1830s to create the 25-acre (10 ha) Greenlawn Cemetery on the city's southwest side.[3] During the Civil War, Greenlawn was quickly filling with burials of Union soldiers and Confederate prisoners of war and faced encroachment from west side industrial development.[4] By the end of the 1870s it was closed to further interments due to lack of space.[3]

The normal demands of a growing city, along with the capacity issues at Greenlawn, prompted a group of Indianapolis's civic-minded men to establish a new and larger cemetery within five miles of the city. On September 12, 1863, the men met with John Chislett Sr, a Pittsburgh landscape architect and cemetery superintendent, to discuss ideas for a cemetery that would be based on the park-like settings becoming popular in Europe, most notably the Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[5] On September 25, 1863, the group formed the Association of Crown Hill.[2] Its selection committee bought a 166-acre (67 ha) farm and tree nursery owned by Martin Williams for $51,500. The site for the new cemetery at Strawberry Hill, a high point overlooking Indianapolis, was 2.8 miles (4.5 km) northwest of the city. The committee also acquired adjacent acreage of naturally rolling terrain from other sources.[2] On October 22, 1863, a 30-member Board of Corporators (trustees) formally established Crown Hill as a privately owned cemetery.[6][7]

Once the initial land was secured, the board hired Chislett's son, Frederick, as Crown Hill's first superintendent. He arrived in Indianapolis with his wife and children on December 31, 1863. Frederick supervised the construction of the cemetery's first roads and developed the property's grounds based on the landscape designs of his father and Prussian horticulturalist Adolph Strauch.[8] The design retained many of the cemetery's natural features and laid out winding roads to create a landscape in the Victorian Romantic style.[9] The cemetery's first main entrance was off old Michigan Road (later known as Northwestern Avenue and currently as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard).[10]

Crown Hill Cemetery was dedicated on June 1, 1864.[11] The first burial at Crown Hill was the body of Lucy Ann Seaton, aged 33, a young mother who had died of consumption.[2] Later that year, James Pattison built a stone gateway for $2,300 at the cemetery's west entrance off Michigan Road. The cemetery's east entrance at 34th Street opened in 1864.[12] Omnibus transportation reached the cemetery in 1864. Visitors could also travel by steam-powered boat up the Central Canal to reach Crown Hill. Automobiles were allowed on the grounds beginning in 1912.[13]

In 1866, the federal government purchased 1.4 acres (0.57 ha) of land within the grounds of Crown Hill for a national military cemetery. The bodies of more than 700 Union soldiers who had died in Indianapolis during the Civil War were moved from Greenlawn Cemetery to new graves at the National Cemetery.[2] On May 30, 1868, Crown Hill, along with Arlington National Cemetery and 182 others in 27 states, took part in the country's first Memorial Day celebrations. An estimated crowd of 10,000 attended the Crown Hill ceremony, beginning an annual tradition at the site.[14]

By the mid-1800s, Crown Hill was a burial ground as well as a popular location for recreational activities such as picnics, strolls, and carriage rides. It is well known for its views of downtown Indianapolis from "The Crown".[16] In addition to developing the cemetery grounds, Crown Hill's Corporators built new structures on the site. A Gothic chapel and vault was erected in 1875.[2] The main entrance was moved to 34th Street on the cemetery's east side, where the cemetery's Waiting Station building and a three-arched gateway were erected in 1885. A new gate and gatehouse were built at the west entrance in 1900 to replace earlier structures that were demolished.[17] Over several decades Crown Hill's grounds expanded to include substantial parcels of land north of 38th Street (known then as Maple Road). In 1911, the acquisition of 40 acres (16 ha) at the northwest corner of Crown Hill made the 550-acre (220 ha) grounds the third largest nongovernmental cemetery in the United States.[18]

Crown Hill's Pioneer Cemetery was established on the north grounds in 1912. The bodies of 1,160 early settlers from Greenlawn Cemetery were moved to this new section at Crown Hill. The remains of 33 people from Rhoads Cemetery, established on the city's west side in 1844, were interred in the Pioneer Cemetery in 1999. Bodies from the Wright-Whitesell-Gentry Cemetery located near Castleton on the city's northeast side were moved to the Pioneer Cemetery in 2008–09.[19]

The cemetery's grounds continued to change. In 1914, landscape architect George Kessler designed a brick and wrought-iron fence nearly three miles (4.8 km) long. It was completed in the early 1920s and surrounded three quarters of the cemetery's south grounds and the southern end of the north grounds along 38th Street. A bridge/underpass that became known as the Subway passed beneath 38th Street to connect the north and south grounds.[20] Although Crown Hill faced competition from other cemeteries in the area, it continued to expand. More than 100,000 people were buried there by the late 1930s and more than 155,000 by the late 1970s.[21] The cemetery's Community Mausoleum was formally dedicated in 1951. Building five of the Garden Mausoleums, a series of outdoor mausoleums, was completed in 1962. A new administrative building by Bohlen and Burns was dedicated in 1969.[22] By the early 1980s, Crown Hill was valued at nearly $3 million. Its annual sales were estimated at $250,000, with an operating budget of $895,000. The cemetery employed 15 salaried employees, 21 full-time maintenance workers, and 25 seasonal workers.[23]

Preservation of the cemetery's monuments and structures remained an ongoing concern to Crown Hill's board. The Crown Hill Heritage Foundation, a nonprofit corporation, was established in 1984 to raise funds for restoration of the cemetery's historic buildings and its grounds. By 1997 the foundation had raised $1.8 million, with an additional $3.2 million raised later, to restore the Gothic Chapel and make other improvements to the cemetery. In the 1990s Crown Hill added a mortuary and a new crematorium.[24]

On February 28, 1973, Crown Hill Cemetery, including the National Cemetery, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The National Cemetery portion, which is listed separately, was added to the National Register on April 29, 1999.[25]

The first African American female, Cynthia Strayhorn Whisler,[26] served as the managing director of Crown Hill Cemetery in 1996. Milton O. Thompson, a lawyer, former deputy Marion County prosecutor, and founder of a sports and entertainment management company became the board's first African American member. Hilary Stour Salatich, a Conseco executive and civic leader, became the first female corporator in 1997.[27]

In 2007, Gibraltar Remembrance Services began managing Crown Hill Cemetery.[28] Service Corporation International acquired Gibraltar Remembrance Services in 2018.[29]

Special sections

National Cemetery

In 1866 the U.S. government authorized a U.S. National Cemetery for Indianapolis as a burial site for Union soldiers who died in military camps and hospitals near the city during the Civil War. The National Cemetery is located on 1.4 acres (0.57 ha) within the grounds of Crown Hill in Section 10 The federal government purchased the site from Crown Hill's board for $5,000. On October 19, 1866, the remains of the first Union soldier were removed from Greenlawn Cemetery and interred at the National Cemetery at Crown Hill. By November 1866, the bodies of 707 soldiers had been moved from Greenlawn to the National Cemetery. As of December 31, 1998, the National Cemetery is filled. It encompasses 795 burial sites.[25][30]

Confederate soldiers' burials

Crown Hill is also a burial site for Confederate soldiers who died at Camp Morton, a prison camp located north of Indianapolis. In 1931, when industrial development around Greenlawn Cemetery required the bodies of the Confederate prisoners to be moved, their remains were interred in a mass grave known as the Confederate Mound in Section 32 at Crown Hill. In 1993 a memorial with ten bronze plaques listing the names of the 1,616 Confederate soldiers and sailors who died at Camp Morton was dedicated at the site.[31][32][33]

Field of Valor

Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq prompted expansion of Crown Hill's military sections to include the Field of Valor on 4 acres (1.6 ha) of the north grounds. It was dedicated on Veterans Day, November 11, 2004. The Eternal Flame and Eagle Plaza installed in front of the memorial were dedicated on Veterans Day in 2005.[34]

Nature

Wildlife abounds in Crown Hill Cemetery, which serves as a large refuge for birds, white-tailed deer, and small animals. The cemetery's grounds are home to more than 10,000 trees of some 130 unique species. In 2022, Crown Hill earned Level II Accreditation by the ArbNet Arboretum Accreditation Program.[35]

Artworks

There are many works of art on the property, some of which are freestanding, but most of which are associated with a gravesite. Notable examples include:

- James Whitcomb Riley's Tomb: Following Riley's death on July 22, 1916, Crown Hill's board offered his family the prestigious site at "The Crown", the summit of Crown Hill that overlooks Indianapolis, as his final resting place. His was buried there on October 6, 1917. Riley's gravesite is marked with a large, open-canopied monument.[36]

- Forrest Memorial: This is the gravesite of Albertina Allen Forrest, wife of Butler University professor and Citizens Gas general manager Jacob Dorrsey Forrest. She died on April 27, 1904. To mark the grave, her husband commissioned Viennese sculptor Rudolf Schwarz, whose work adorns numerous monuments and memorials including the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in Indianapolis, to create "Statue in Repose", a kneeling woman in mourning beneath a couplet from Alfred Lord Tennyson's "In Memoriam". Albertina's husband, who died in 1930, is buried in an unmarked grave beside the memorial.[37]

- Three limestone statues depicting the Greek goddesses Themis, Demeter, and Persephone from the old Marion County Courthouse. The courthouse was demolished in 1962.[38]

- Equatorial Sundial:David L. Rodgers was commissioned to create the functional sundial in 1985. It was fabricated of Indiana limestone in Bloomington, Indiana, and installed in front of the Community Mausoleum in 1987.[39]

- The Hoosier Artists Contemporary Sculpture Walk: Established to mark Crown Hill's 140th anniversary, the walk includes works by ten artists, including Michael B. Wilson's "Social Attachments" and Eric Nordgulen's "Antenna Man".[40]

- Holcomb Mausoleum Door: Part of a memorial for James Irving Holcomb, an Indianapolis industrialist and a Vice President of the Butler University board of trustees

Notable memorials

- Medical Science Donor Memorial, installed in 1991. In 1978 the Anatomical Education Board of the Indiana University School of Medicine purchased Section 41-A to inter the cremated remains of bodies that had been studied. As of 2011 more than one thousand medical donors have been recognized at the memorial.[41]

- Indiana AIDS Memorial, dedicated on October 29, 2000, is the first permanent AIDS memorial located in a cemetery.[42]

- The Heroes of Public Safety monument, dedicated on September 11, 2002, is inscribed with the names of police, firefighters, and other public safety personnel who died in the line of duty.[43]

- The Hearts Remembered Memorial, dedicated on June 4, 2006, remembers the city's orphaned and abandoned children, many of whom were buried in unmarked graves.[44]

Structures

- Gothic chapel – Indianapolis architect Diedrich A. Bohlen designed the High Victorian Gothic-style chapel and vault, which were built east of the National Cemetery in 1875 at an initial cost of $38,922. They replaced an earlier vault that was used as temporary storage for bodies awaiting burial. In 1917 D.A. Bolen and Son designed an addition to the structure designed by D. A. Bohlen, the architectural firm's founder. The chapel and vaults were restored in the early 1970s at a cost of $120,000. CSO Architects began a major renovation and expansion in 2001. The project cost $3.2 million and received an excellence in Architecture Award from the American Institute of Architects, Indiana chapter, in 2007.[45][46][47]

- East gate, Waiting Station, and Porter's Lodge – Adolf Scherrer, an Indianapolis architect of Swiss origins, designed the High Victorian Gothic gateway and Waiting Station for the cemetery's main entrance at 34th Street and Boulevard Place. Construction began in May 1885. The three-arched gateway was completed in November 1885, in time for the funeral of vice-president and former Indiana governor Thomas A. Hendricks. The gate was built of Bedford limestone. The Waiting Station exterior is brick and limestone. A gatehouse house that became known as Porter's Lodge at the gate's south side was designed by the Indianapolis architectural firm of Vonnegut and Bohn and built in 1904. The Crown Hill board leased the Waiting Station to Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana in 1970 for one dollar per year, provided the preservation organization agreed to restore the historic structure. The restoration was completed by February 1971. HLFI moved to offices on Michigan Street in 1990 and the Waiting Station was leased until the mid-1990s, when Crown Hill began using it for office space. Crown Hill spent an additional $500,000 to restore the Waiting Station in the late 1990s. It was restored again in 2001 and serves as a meeting place for cemetery tours and programs.[48][49][50][51][52]

- Subway bridge/underpass – The underpass beneath 38th Street that connects the north and south grounds is also known as the Subway. Construction began in 1925 and was completed in 1927 at cost of $170,000. It was restored in the 1980s.[53][39]

- West gate and gatehouse – In 1901 the original west entrance to the cemetery was demolished and an arched Romanesque gate and a gatehouse designed by Indianapolis architect Herbert Foltz was erected at its southwest corner. The west gate was closed in 1965 and demolished the following year.[54][55]

- Masonry fence – In 1914 George Kessler designed a brick and wrought-iron fence to replace the cemetery's wood and wire fencing. The masonry fence surrounded three quarters of the south grounds and the southern end of the north grounds along 38th Street. It cost nearly $138,000. The fence has a 4-foot (1.2 m) thick concrete base, brick supports 8.5 feet (2.6 m) in height, and sections of wrought iron measuring 25 feet (7.6 m) in length that rest on brick support walls. Brick pillars at the entrances are more than 12 feet (3.7 m) tall. Construction of the fence, which is approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) long, was completed in 1920. A multi-year restoration costing $600,000 began in 1985.[38][56]

- Mausoleums – Crown Hill contains several family and communal mausoleums: Community Mausoleum, designed by D. A. Bohlen and Company, was completed in the early 1950s. Its exterior is made of Indiana Bedford limestone; the interior is marble. Abbey Mausoleum, which was planned in 1993, is designed by Patrick L. Fly and cost $1.3 million. It is built of Indiana limestone and Carnelian granite.[22][57]

- Superintendent's residence – A home for the superintendent remained on cemetery grounds until 1950. D. A. Bohlen designed a three-story Victorian house to replace a log cabin structure in the late 1860s. Fire destroyed the Victorian residence in 1913, but a new three-story brick home was already under construction as its replacement. The brick residence was removed from Crown Hill in 1950.[47][58]

- Administrative offices – A building erected at 38th and Clarenden Streets in 1969 serves as Crown Hill's business offices.[49]

- Mortuary and crematorium – Groundbreaking for a $1.5 million mortuary took place in May 1992. Architect J. Stuart Todd drew up the plans. The funeral home opened on March 1, 1993. Gibralter Remembrance Services, LLC, who purchased the mortuary in 2006, built a 9,500 square foot expansion. A new crematorium was added in 1990.[59]

Notable interments

Political and civil rights figures

- Benjamin Harrison, 23rd president of the United States, along with his first wife, Caroline Harrison;[60] his second wife, Mary Dimmick Harrison;[61] his son Russell Benjamin Harrison; and his daughter Mary Harrison McKee.

- Vice Presidents of the United States Charles W. Fairbanks, Thomas A. Hendricks, and Thomas R. Marshall.[62]

- Vice presidential nominees George Washington Julian, William Hayden English, and John W. Kern.[62][63]

- Indiana Governors Noah Noble, David Wallace, James Whitcomb, Abram A. Hammond, Oliver P. Morton, Thomas A. Hendricks, Albert G. Porter, Ira Joy Chase, Winfield T. Durbin, Thomas R. Marshall, and Robert D. Orr.[60][64]

- United States Senators Oliver H. Smith, Thomas A. Hendricks, Benjamin Harrison, Charles W. Fairbanks, Albert J. Beveridge, John W. Kern, Joseph E. McDonald, Thomas Taggart, David Turpie, Homer E. Capehart, Robert Hanna, and Harry S. New.[62]

- U.S. Representatives George W. Julian, General Ebenezer Dumont, Albert Porter, John H. Farquhar, Ralph Hill, Franklin Landers, Samuel M. Moores, William E. Niblack, and Julia Carson.[65][66]

- Mayors of Indianapolis including Caleb Scudder, James McCready, Henry F. West, Samuel D. Maxwell, John Caven, Daniel W. Grubbs, Caleb S. Denny, Thomas L. Sullivan, Thomas Taggart, Charles A. Bookwalter, John W. Holtzman, Samuel L. Shank, Joseph E. Bell, Charles W. Jewett, John L. Duvall, Claude E. Negley, Reginald H. Sullivan, Walter C. Boetcher, Robert Tyndall, George L. Denny, and Christian J. Emhardt.[60][66]

- Allen M. Fletcher, Governor of Vermont

- Addison C. Harris, U.S. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary (ambassador) to Austria-Hungary.[67]

- William Henry Harrison Miller, U.S. Attorney General.[60]

- William D. McCoy, United States Ambassador to Liberia[68]

- Meredith Nicholson, author and U.S. Minister to Paraguay, Venezuela, and Nicaragua[69][70]

- May Wright Sewall, women's rights advocate.[71]

- William S. Taylor, Governor of Kentucky

- William F. Turner, first Chief Justice of the Arizona Supreme Court.[72]

- Henry Lane Wilson, Ambassador to Mexico and U.S. Minister to Chile and to Belgium.[67]

- Zerelda G. Wallace, temperance advocate and suffragette, second wife of governor and congressman David Wallace, Lew Wallace's stepmother, and sister-in-law of James Gatling.[73]

- Christopher T. Gonzalez, LGBT and AIDs activist, along with his life partner Jeff Werner.

Military figures

- American Civil War generals for the Union army: Thomas Armstrong Morris, Edward Richard Sprigg Canby, Jefferson C. Davis, Abel Streight, George Francis McGinnis, John Parker Hawkins, Robert Sanford Foster, John Coburn, Frederick Knefler, and George Henry Chapman.[74][75]

- The remains of 1,616 Confederate soldiers who died during their confinement at Camp Morton, a Union prison camp in Indianapolis. Their remains were transferred to Crown Hill in 1931.[31]

- Two British Commonwealth service personnel are buried in this cemetery, one from each World War: Captain Joseph Hammond of the Royal Air Force, killed in 1918,[76] and Warrant Officer Thomas Taggart Young, Royal Canadian Air Force, who died in 1942.[77]

- Charles W. Brouse, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient[78][79]

- James H. Kasler, Korean and Vietnam War fighter pilot and POW; only recipient of three Air Force Crosses[80]

- John Swanson Congressional Medal of Honor recipient[78][79]

- Roscoe Turner, aviator, winner of a Distinguished Flying Cross, and transcontinental speed recordholder.[81]

Sports figures

- James A. Allison, Frank Wheeler, Arthur Newby, and Carl Fisher, founders of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.[60][82]

- Indianapolis 500 winners Floyd Davis, Louis Schneider, Howdy Wilcox[82]

- Bob Jenkins, voice of the Indianapolis 500 1990–98

- Erwin "Cannon Ball" Baker, record setting automobile and motorcycle racer.[60]

- William L. "Bill" Garrett, the first African American to play in the Big Ten Conference.[83]

- Robert Irsay, former owner of the Indianapolis Colts.[84]

- Frank McKinney, Olympic gold medalist in swimming, later president of Bank One of Indiana and civic booster.[85]

- Toad Ramsey, Major League Baseball player from 1885 through 1890.

- Stacey Toran, Football defensive back for the Los Angeles Raiders.[86]

- John Woodruff, Olympic gold medalist in track, 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.[87]

Founders and inventors

- Lyman S. Ayres, founder of L. S. Ayres department stores.[88]

- Charles H. Black[67][89][90]

- Ovid Butler, founder of Butler University.[67]

- August Duesenberg and Frederick S. Duesenberg, automotive industrialists[67][89][90]

- Frank P. Fox, Indianapolis 500 driver and owner of the Pope Motor Car Company[67][89][90]

- Howard Garns, inventor of Sudoku

- Richard Jordan Gatling, American inventor, best known for his invention of the Gatling gun.[60]

- John F. Geisse, founder of Target Stores, Venture Stores, and The Wholesale Club.

- Colonel Eli Lilly, founder of Eli Lilly and Company,[60] and several of his descendants, including Josiah K. Lilly Sr., Josiah K. Lilly Jr., Eli Lilly, and Ruth Lilly.[91]

- Daniel Marmon, Early Indianapolis-based automotive manufacturers and a principal of Nordyke Marmon and Company

- Thomas A. Morris, Indiana railroad executive and civil engineer

- David M. Parry, founder of the Parry Auto Company[67][89][90]

- Harry C. Stutz, Indianapolis-based automobile engineer and industrialist.

- Hiram P. Wasson, founder of H. P. Wasson and Company department stores[66]

Arts and media

- James Baskett, the first African American man to win an Academy Award and best known for his role as Uncle Remus in Disney's Song of the South (1946).[69][92]

- Sarah T. Bolton, poet.[93]

- Jacob Cox, portrait and landscape painter.[68]

- Cecil Duane Crabb, ragtime composer.[69]

- William Forsyth, Hoosier Group artist[94]

- Richard Gruelle, Hoosier Group artist[94]

- John Wesley Hardrick, artist

- Frank McKinney "Kin" Hubbard, cartoonist and humorist.[60]

- Etheridge Knight, poet.[95]

- James Whitcomb Riley, poet,[96] best known for his poem "Little Orphant Annie"

- Otto Stark, Hoosier Group artist[94]

- Booth Tarkington, author[60] and winner of two Pulitzer Prizes

Other

- Francis Costigan, pioneer Indiana architect

- John Dillinger, notorious bank robber in the 1930s.[97]

- G. T. Haywood, First Presiding Bishop of the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World.

- Josephine R. Nichols (1838–1897), President, Indiana State Woman's Christian Temperance Union[98]

- Alexander Ralston, surveyor who designed the original plan of Indianapolis in 1821.[99]

Fictional interment

In the book The Fault in Our Stars, as well as the movie adaptation of the same name, the love interest Augustus Waters is buried at Crown Hill in a gravesite facing 38th Street.[100]

Gallery

-

Benjamin Harrison's grave

-

Graves of Confederate prisoners of war who died at Camp Morton

-

Skyline of Indianapolis from Riley's grave

-

Closeup of James Whitcomb Riley's grave

-

John Dillinger's grave

-

Oliver P. Morton's grave

-

Thomas R. Marshall's grave

-

Waiting Station at Crown Hill Cemetery.jpg - April 2016

See also

- List of cemeteries in the United States

- List of cemeteries in Indiana

- List of burial places of presidents and vice presidents of the United States

- List of attractions and events in Indianapolis

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Sloan, Sarah (1973). The True Treasure of Crown Hill Cemetery. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association. p. 1.

- ^ a b Sanford, Wayne L. (1988). Crown Hill, 1863–1988: 125th Anniversary Edition. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association. p. 15.

- ^ Wissing, Douglas A.; Marianne Tobias; Rebecca W. Dolan; Anne Ryder (2013). Crown Hill: History, Spirit, and Sanctuary. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 2, 7. ISBN 978-0871953018.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 7–8, 13.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 14, 17, 241–43.

- ^ Sanford, p. 1.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 13, 17.

- ^ National Park Service.

- ^ Sloan, pp. 1, 17.

- ^ Wissing, p. 17.

- ^ Sanford, p. 3.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 31, 38–39, 101.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 36–37.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about Crown Hill Cemetery Tours" (PDF). Crown Hill Cemetery. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Sanford, pp. 3, 17.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 38, 80, 123.

- ^ Wissing, p. 296.

- ^ Sloan, pp. 1, 3.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 128, 155, 193.

- ^ a b Sanford, p. 10.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 225, 230, 233.

- ^ a b Sammartino, Therese T. (April 29, 1999). "National Registration of Historic Places Registration Form: Crown Hill National Cemetery" (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ^ Department of Periodontics and Allied Dental Programs, IU School of Dentistry (April 4, 2012). "The Practicing Academic" (PDF). IUPUI Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2022. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 241–243.

- ^ "Gibraltar deal eases Crown Hill worries". February 6, 2007. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Recent Acquisitions". Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 33, 35.

- ^ a b Conn, Earl L. (2006). My Indiana: 101 Places to See. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0871951953.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 1–2, 164.

- ^ Sanford, p. 8.

- ^ Wissing, p. 293.

- ^ Healy, Thomas P., ed. (January 2023). "Crown Hill Cemetery Grounds Receive Arboretum Accreditation". Midtown Indy. Vol. 2, no. 1. Indianapolis: Midtown Indianapolis Inc. p. 19. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Wissing, p. 113.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 130, 136–38.

- ^ a b Sanford, p. 20.

- ^ a b Wissing, p. 228.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 286, 293.

- ^ Wissing, p. 255.

- ^ Wissing, p. 271.

- ^ Wissing, p. 274.

- ^ Wissing, p. 295.

- ^ "Crown Hill Cemetery, Chapel and Vault, Thirty-fourth Street, Indianapolis, Marion County, IN". Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 42, 124, 188, 286.

- ^ a b Sanford, p. 18.

- ^ "Crown Hill Cemetery, Gateway, 3402 Boulevard Place, Indianapolis, Marion County, IN". Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Sanford, p. 17.

- ^ "Crown Hill Cemetery, Office Building, 3402 Boulevard Place, Indianapolis, Marion County, IN" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ "Crown Hill Cemetery, Office Building, 3402 Boulevard Place, Indianapolis, Marion County, IN: Supplement" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 80, 83, 123, 188, 230, 286.

- ^ Sanford, p. 19.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 123, 187.

- ^ Nicholas, p. 111.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 124, 228.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 182, 188, 228.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 42, 123.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 233, 270–71.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Our Hoosier Heritage. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association. 1970.

- ^ Sanford, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Sanford, p. 22.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Wissing, p. 303.

- ^ Wissing, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Sanford, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Our Hoosier Heritage in Crown Hill Cemetery: A Place of History and Scenic Beauty. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association. 1966.

- ^ a b Sandford, p. 9

- ^ a b c Wissing, p. 158.

- ^ Sanford, p. 4.

- ^ Boomhower, Ray E. (2007). Fighting for Equality: A Life of May Wright Sewell. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0871952530.

- ^ Goff, John S. (Summer 1978). "William F. Turner, First Chief Justice of Arizona". Journal of Arizona History. 19 (2). Arizona Historical Society: 207. ISSN 0021-9053. JSTOR 42678105.

- ^ Wissing, p. 70.

- ^ Nicholas, Anna (1928). The Story of Crown Hill. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Association. pp. 167–73, 177, 180–182. ISBN 978-0871953018.

- ^ Wissing, p. 64.

- ^ "Joseph Joel Hammond – The Canadian Virtual War Memorial – Veterans Affairs Canada". www.veterans.gc.ca. February 20, 2019. Archived from the original on December 8, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Casualty Details: Young, Thomas Taggart". Commonwealth War Games Commission. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Wissing, p. 63.

- ^ a b Sanford, p. 5.

- ^ Richards, Phil (May 26, 2014). "Col. James Kasler, 'Indiana's Sgt. York,' was fighter, survivor". Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ Wissing, p. 194.

- ^ a b "Indianapolis Auto greats" (PDF). Celebrating Automotive Heritage at Crown Hill Cemetery. Crown Hill Cemetery. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ Wissing, p. 211.

- ^ Wissing, p. 257.

- ^ Rovira, Ivonne (November 28, 2011). "Crown Hill Cemetery: Resting Place for Notable and Notorious". Hello Indianapolis City Guide. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ Madden, W.C. (2004). Crown Hill Cemetery. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1439614891.

- ^ Wissing, p. 306.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b c d Sanford, pp. 9–10, 14.

- ^ a b c d Wissing, pp. 103–04, 155.

- ^ Wissing, pp. 195–96, 304.

- ^ Sanford, p. 7.

- ^ Wissing, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Wissing, pp. 106–07.

- ^ Wissing, p. 248.

- ^ Wissing, p. 110.

- ^ Wissing pp. 160–64.

- ^ "Josephine R. Nichols Dead". The Indianapolis News. April 9, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved February 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Sanford, p. 23.

- ^ Lindquist, David. "John Green looked to Indy sites for 'TFIOS' settings". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

References

- "Crown Hill Cemetery". National Park Service. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- Conn, Earl L. (2006). My Indiana: 101 Places to See. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0871951953.

- Nicholas, Anna (1928). The Story of Crown Hill. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Association.

- Our Hoosier Heritage. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association. 1970.

- Our Hoosier Heritage in Crown Hill Cemetery: A Place of History and Scenic Beauty. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association. 1966.

- Sanford, Wayne L. (1988). Crown Hill, 1863–1988: 125th Anniversary Edition. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association.

- Sloan, Sarah (1973). The True Treasure of Crown Hill Cemetery. Indianapolis: Crown Hill Cemetery Association.

- Wissing, Douglas A.; Marianne Tobias; Rebecca W. Dolan; Anne Ryder (2013). Crown Hill: History, Spirit, and Sanctuary. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0871953018.

External links

- Official website

- Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Crown Hill Cemetery

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Crown Hill National Cemetery

- Crown Hill Cemetery at Find a Grave

- Crown Hill National Cemetery at Find a Grave

- Historic American Landscapes Survey documentation:

- HALS No. IN-3-A, "Crown Hill Cemetery, Crown Hill National Cemetery", 16 photos, 2 photo caption pages

- HALS No. IN-3-B, "Crown Hill Cemetery, Confederate Plot", 6 photos, 1 photo caption page