Conservation and restoration of film

The conservation and restoration of film is the physical care and treatment of film-based materials (plastic supports). These include photographic film and motion picture film stock.

Film supports

Cellulose nitrate

Cellulose nitrate (c. 1889 – c. 1950) is the first of film supports. It can be found as roll film, motion picture film, and sheet film. It is difficult to determine the dates when all nitrate film was discontinued, however, Eastman Kodak last manufactured nitrate film in 1951.[1] Cellulose nitrate is cellulose fibers modified with nitric acid to create a nitrocellulose solid.[1] Cellulose nitrate is extremely flammable and capable of burning even in the absence of oxygen and underwater. It has been the cause of many fires and losses of motion picture films, photographic materials, and archival records.[1]

Cellulose acetate

Cellulose acetate is also known as "safety" film and started to replace nitrate film in still photography in the 1920s.[1] There are several types of acetate that were produced after 1925, which include diacetate (c. 1923 – c. 1955), acetate propionate (1927 – c. 1949), acetate butyrate (1936–present), and triacetate (c. 1950 – present).[1] The earliest, diacetate, was found to be inferior to nitrate because it had high shrinkage rates.[1] Eastman Kodak then worked with mixed esters of cellulose to create acetate butyrate and acetate propionate, which were used for sheet film, X-rays, amateur roll film, and aerial maps, but they were still found to be inferior to nitrate by the motion picture industry.[1] Triacetate was then produced and is still in production for roll film today.

Polyester

Polyester (1955–present) started to replace acetate as a film support for many types of sheet film; however, due to its rigidity, it cannot be used as roll film.[1] Polyester can also be identified as "safety" film. It is inherently more stable than both cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate, because it is a synthetic polymer that is inert (chemically inactive). It shows exceptional chemical stability and physical performance.[1] A polarization test can be used to identify polyester from cellulose acetate or nitrate. When viewed between cross-polarized filters, polyester will exhibit red and green interference colors, similar to a rainbow moiré pattern. Nitrate and acetate films will not show these interference colors.[2]

Film formats

Motion picture

Perforated roll films create for sale or theatrical distribution typically found in 35 mm, but also 65 mm, 70 mm, and other gauges. Seen on reels, rolls, strips or frames. Can be nitrate, acetate, or polyester.[3]

Small gauge motion picture

Found in short rolls and may be cut after processing into strips or single images. Includes 35 mm, still-camera negatives, 120 and 220 size roll films and slide (transparency) films. Can be nitrate, acetate, or polyester.[4]

Still photo (roll)

Found in short rolls and may be cut after processing into strips or single images. Includes 35 mm, still-camera negatives, 120 and 220 size roll films and slide (transparency) films. Can be nitrate, acetate, or polyester.[5]

Magnetic soundtrack

Roll film with a ferromagnetic coating. Seen on rolls or reels and a variety of gauges. Can be acetate or polyester.[6]

Aerial

Sheets or roll film in sizes of 4x5, 8x10, and 10x10; can splice together single sheets into larger rolls. Can be nitrate, acetate, or polyester.[7]

Microfilm

Roll film in 35mm and 16mm widths, and 105mm microfiche. Can be reels, rolls, cards, or sheets. Can be acetate or polyester.[8]

Sheet

Single-sheets of film commonly found in sizes of 4x5, 5x7, and 8x10 inches. Also known as flat film. Can be nitrate, acetate, or polyester.[9]

X-Ray

Large format sheet film, 8x10 or larger. Can be nitrate, acetate, or polyester.[10]

Agents of deterioration

Temperature and humidity

The deterioration of both cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate negatives is highly dependent on temperature and relative humidity.[2] Storing materials at room temperature or warmer, and with high humidity, will inevitably cause deterioration. Extreme fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity will rapidly increase the rate of deterioration.

Exposure to light

Permanent display of photographs is not recommended; most photographic materials are vulnerable in varying degrees to deterioration caused by light. Damage caused by light is cumulative and depends on the intensity, length of exposure, and the wavelength of the radiation. Visible light in blue part of the spectrum (400 to 500 nanometers), and ultraviolet (UV) radiation (300 to 400 nanometer region) are especially damaging. Sunlight and standard fluorescent light are both strong sources of UV. Color slides are particularly susceptible to fading when exposed to both visible and UV light.[11]

Pollution

Air pollution attacks photographs in the form of oxidant gases, particulate matter, acidic and sulfiding gases, and environmental fumes. Oxidant gases are composed primarily of pollution created by burning fossil fuels such as coal and oil. This can cause photographic images to fade. Particulate matter, such as soot and ash particles from manufacturing processes, exists in abundance outdoors and can enter the library or archives through heating and cooling ducts, doors, and windows. Particulates, which may be greasy, abrasive, and chemically or biologically active, settle on shelves and on collection materials and create dust that is spread to other materials when they are handled. The by-products of combustion combined with moisture in the atmosphere pose another risk to photographic materials. These acids attack all components of photographs and cause silver images to fade and paper and board supports to discolor and become brittle. Environmental fumes can be especially damaging to photographic images even in small quantities.[11]

Poor storage

Poor storage, such as lack of enclosures, can lead to deterioration through exposure to light and pollution. Additionally, materials that are not carefully and safely stored can rub against each other, causing scratching and abrasions. Storing film materials in basements, attics, or garages can cause rapid deterioration through extreme temperature and humidity fluctuations, but also through exposure to insects and rodents.[12] Storing materials on the floor can also increase the risk of damage by water leaks, insects and rodents.[11]

Poor handling and use

Film can be mishandled causing physical damage. Working at dirty workstations or using bad rollers for motion picture film can cause dirt, scratches, and abrasions. Tears can occur when the film is stressed during winding or projection, in addition to improper threading.[13] Repeated use, including the repeated insertion and removal of film from sleeves can also cause scratches and abrasions. Ignorance, neglect, and carelessness account for a significant percentage of damage to photographs.[11]

Improper chemical processing

Major silver deterioration occurs when photographs are not correctly processed and washed. Over time, residual fixer left in the photograph causes the image, binder, and support to turn yellow or brown and the silver image to fade. High temperature and humidity speed this process. Photographs that were not well fixed remain light sensitive and may darken when exposed to light.[11]

Nitrate deterioration

Cellulose nitrate is chemically unstable; decay is irreversible and autocatalytic. When the film deteriorates, it turns yellow, brittle and sticky. The off-gassing of nitrate produces hazardous and corrosive products (nitrogen oxides form nitric acid) along with an acrid smell that cause fading of the silver image, decomposition of the gelatin binder, and the eventual destruction of the plastic support and image material.[1] These products (nitric acid, nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide) are destructive to other film-based negatives, and especially to photographic prints. Other artifacts, metals for instance, will be harmed by proximity to deteriorated nitrate material. Such gasses can cause skin, eye, and respiratory irritations. Allergic sensitivity has also been noted, as has dizziness and lightheadedness.[14]

Types of deterioration

Embrittlement

Caused by the loss of elasticity in the plastic film base over time. The film can snap or break under strain, and will no longer have flexibility.[15]

Shrinkage

The loss of the original dimensionality of the film and is irreversible.[16]

Distortion

Distortion is caused by uneven shrinkage across a film's dimension and starts to warp or curl. This can be due to the difference in shrinkage between the film and emulsion layers, or areas of the film that start to shrink more than other areas. Temporary distortion can be reversed, but permanent distortion cannot.[17]

Gelatin and base decomposition

As the film is exposed to moisture, heat, and acids, nitrogen oxides are produced, which creates nitric acid. These promote silver corrosion and decompose the gelatin emulsion layer. The chemical reactions that occur cause further nitrate decay. Softness and stickiness occur and the image starts to fade away. This is irreversible.[18]

Silver mirroring and fading (black and white)

When exposed to moisture in the environment and various pollutants, the image silver will corrode, creating a reflective metallic sheen on the emulsion side. Typically starts at the edges of the film. Poor quality enclosures and storage can hasten the process.[19]

Redox blemishes

These small pink, orange or yellow spots can found in the image area and are often found in microfilm. These are created by local oxidation of metallic silver due to moisture and pollutants in the environment.[20]

Levels of deterioration

Deterioration of nitrate film is often categorized in six stages, or levels:[2]

- Level 1: No deterioration

- Level 2: The film turns yellow. The silver gelatin can begin to mirror

- Level 3: The film becomes sticky and emits a strong noxious odor (nitric acid)

- Level 4: The film becomes an amber color and the image starts to fade

- Level 5: The film is soft, can adhere to adjacent film, enclosures and other materials

- Level 6: The film degenerates into a brownish acid powder

Acetate deterioration

While considered "safety film" as it produces less hazards than nitrate, cellulose acetate still faces stability issues. The deterioration of acetate is autocatalytic just like nitrate: once the deterioration process starts, the degradation products induce further deterioration.[2] If not properly cared for and preserved, cellulose acetate will become acidic, and face many of the same issues that nitrate faces. Deteriorated acetate can also emit a noticeable odor, and can cause the same skin, eye, and respiratory irritations as nitrate does, in addition to dizziness and lightheadedness.[14]

Types of deterioration

Vinegar syndrome

Vinegar syndrome is the release of acetic acid, which produces a strong vinegary odor.[2] AD strips are dye-coated paper strips that can detect and measure the severity of vinegar syndrome in film collections. The strips change color, shifting from a blue to green to level, based on the level of acidity found. If the AD strip level remains at blue, the film is in good condition and no deterioration is present. If the AD strip level turns yellow, the film condition is in critical condition, creating a possible handling hazard, and should be frozen immediately.[21]

Embrittlement

Caused by the loss of elasticity in the plastic film base over time. The film can snap or break under strain, and will no longer have flexibility.[15]

Anti-halation

The acetic acid that is released in cellulose acetate negatives can trigger the retrieval of the color dyes in the backing layer, known as the anti-halation layer, giving the negative a blue or pink appearance. This is irreversible.[22]

Plasticizer exudation

Plasticizer additives that move to the surface of the film and form crystals or bubbles as the acetate film deteriorates. This is irreversible.[23]

Shrinkage

The loss of the original dimensionality of the film and is irreversible.[16]

Distortion

Distortion is caused by uneven shrinkage across a film's dimension and starts to warp or curl. This can be due to the difference in shrinkage between the film and emulsion layers, or areas of the film that start to shrink more than other areas. Temporary distortion can be reversed, but permanent distortion cannot.[17]

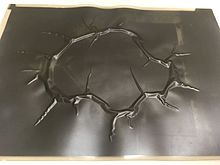

Channeling and delamination

As the film decays, acetic acid is released from the film support, which causes the gelatin layer to separate from the film support. This is a form of advanced acetate decay and can be accompanied by embrittlement and the exudation of plasticizers.[24] While delamination is irreversible, skilled professionals can perform conservation treatments to save the image.[24]

Dye fade (color)

Found in color films, dye fading reduces the overall density of the image resulting in loss of contrast and shifts in color balance. This is irreversible, however, digital restoration techniques can be used to approximate the original color balance and information.[25]

Silver mirroring and fading (black and white)

When exposed to moisture in the environment and various pollutants, the image silver will corrode, creating a reflective metallic sheen on the emulsion side. Typically starts at the edges of the film. Poor quality enclosures and storage can hasten the process.[19]

Redox blemishes

These small pink, orange or yellow spots can found in the image area and are often found in microfilm. These are created by local oxidation of metallic silver due to moisture and pollutants in the environment.[20]

Levels of deterioration

Deterioration of cellulose acetate is often categorized into the following levels, or stages:[2]

- Level 1: No deterioration

- Level 2: Negatives start to curl and anti-halation colors released

- Level 3: The onset of vinegar syndrome (vinegar odor) as well as shrinkage and brittleness.

- Level 4: Warping

- Level 5: Formation of bubbles and crystals

- Level 6: Formation of channeling

Polyester deterioration

Because polyester is an inert and stable plastic, it does not possess the same deterioration concerns as celluloid films. Polyester can be stored at room temperature and does not need cold storage for preservation. Polyester is also used as an archival enclosure option for materials, such as Mylar and Melinex brand products.

Types of deterioration

Dye fade (color)

While polyester film is stable, the chromogenic dyes found in color negatives on polyester supports are not permanent and may fade rapidly at room temperature.[1]

Preventive conservation strategies

Preventive conservation actions such as environmental monitoring, good storage, and promoting proper handling through staff and user education, will have a lasting, positive impact on the preservation of a collection.[11]

Temperature and humidity controls

Keeping film cold and dry is ideal; however, a cool environment (40 to 60 degrees F) is better than room temperature or higher as it will slow down the deterioration process. The best storage conditions for both black & white and color cellulose acetate film are cold (-15° to 4°C/ 5° to 39°F) and dry (30% to 40% relative humidity) environments for cellulose nitrate, cellulose acetate films in both color and black and white, and color on polyester supports.[1] Black and white film on polyester supports may be stored at a temperature of 18º C (65º F) or lower and a relative humidity of 30% to 40%.[1]

Cold storage

Freezing film is the ideal temperature to preserve film for the long-term. At freezing temperatures, the natural decomposition of cellulose nitrate and acetate is slowed down. Cold storage is predicted to extend the life of acetate negatives by a factor of ten or more.[2]

Storage control

Three layers of protection are recommended for the storage of film base photographic materials.[2] Negatives and positives should be placed in sleeves or envelopes, which are then placed in a box or drawer, and these boxes or drawers on shelves or in a cabinet. Motion picture film and microfilm should be stored in unsealed containers in cabinets or on shelves.[2] Labels such as acid-free, lignin-free, or buffered do not guarantee that a material is safe to use with photographic materials. Chemically inert papers may be harmful to the photographic image; the only way to be certain of the stability of the paper is to purchase materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (PAT).[26] There are also considerations to be made regarding paper or plastic enclosures. Factors such as use, handling, and cost should be considered when selecting archival storage materials.[26] There are several resources provided in the external links section below that can assist with the selection of proper storage materials for photographic materials.

Film materials should be stored in interior rooms away from exterior walls and places with extreme temperature fluctuations. Furthermore, film materials should not be stored near sources of heat (sunlight, radiators, heaters), water (bathrooms, sprinklers), or near chemical or exhaust fumes.[12] Storage environments should be regularly monitored to check temperature and humidity controls, HVAC systems, and pest-free.[12] Quantities of nitrate film in excess of 25 pounds are subject to storage and handling standards prescribed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).[27]

Seriously deteriorated negatives of any type should be isolated from those in good condition.[14]

Light control

Photographic materials should always be covered when not in use. Storing film-based materials in containers and boxes will keep light away from the materials. When exhibiting or using these materials, a low light level should be used. The installation of low-UV-emitting bulbs or UV-absorbing fluorescent bulb sleeves can help eliminate this problem. UV filtering window glazing or the installation of window shades may also help. Low- UV-emitting bulbs and sleeves are available from several manufacturers. Light levels in storage areas can also be controlled by the use of timed shut-off switches. Dark cloths or sheets of folder stock (heavyweight paper) or mat board should be available in reading rooms for covering objects when not in use by readers.[11]

Pollution control

Air entering the storage area should be filtered and purified to remove particulate and gaseous matter. A well-designed filtration system includes cellulose or fiberglass filters that remove particulate matter, and chemical absorption system that filters out gaseous pollutants. Air filters must be changed regularly to be effective. Air circulation should also be checked periodically.[11]

Handling control

When handling film, the user should always have clean hands and wear gloves (cotton or nitrile) to avoid fingerprints or scratches. Always handle the film by the edge to avoid touching the image surface.[11] Users must be careful when removing film from enclosures to avoid scratches or abrasions. Never force rolled film flat if it is brittle, as it can snap or break. Always work in an uncluttered and clean environment that is well-lit and ventilated.[28] It's also beneficial to avoid wearing jewelry, such as long necklaces, that can accidentally scratch the film when being examined. Food and drinks should be kept in a separate room or a safe distance from the film materials. It is also advisable to limit exposure times to celluloid film, wear googles and a respirator.[14]

Digitization

Any negatives that show signs of deterioration should be digitized as soon as possible. Without immediate restoration followed by a change to proper long-term storage, the environmental factors that caused the early signs of damage will continue, leading eventually to irreparable damage and permanent loss of the film's content. Nitrate and safety negatives that need to be handled but are in good condition should still generally be digitized. The digital image can then be used as an access copy while the original remains in cold storage.[2] A wide array of digital systems are available for capturing and storing photographic images, and an institution should have a digital preservation policy in place. Digitization requires active management to ensure the digitized copies are not corrupted or lost. There are many factors to consider when digitizing photographic materials.[2] The Northeast Document Conservation Center provides information and resources on Digital Preservation.

Duplication

Transferring negatives to a more stable support such as polyester is the best way to preserve the longevity of the images.[2]

Conservation treatments

Deteriorated film that requires conservation work should be conducted by a photograph conservator. There are several resources available to aid in finding a conservator, including the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC), the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC), and the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA).

Conservation treatments for nitrate

It is not recommended to perform conservation treatments on nitrate. The best options are cold storage to prevent further deterioration (especially if the film is found to be in the lower levels of deterioration), digitize the nitrate film, or duplicate the nitrate film onto a more stable support like polyester. If the nitrate is found to be at the higher levels of deterioration, it is recommended that the original nitrate film be destroyed due to the health and safety hazards.[14]

Conservation treatments for acetate

Cold storage is the best option for preventive conservation of cellulose acetate film as it slows down the deterioration process. As with nitrate, it is also suggested that digitization and duplication efforts are useful in providing access copies. However, it is possible to perform some conservation treatments on acetate film.

"Stripping" is a technique that is used by trained conservators on channeled acetate film. This process allows the conservator to separate the gelatin emulsion layer from the deteriorating acetate film base in a bath and then reattach or duplicate the gelatin emulsion layer onto another sheet of film. This process is quite tedious and expensive, and not always successful, therefore it is not always a viable option for everyone.[29]

Obstacles in conservation and restoration

Irreversible damage or deterioration

As described above, celluloid materials are chemically unstable and will naturally deteriorate over time.[1] Once the materials have reached high levels of deterioration, the film often faces irreversible damage, including image loss. It's important to digitize or duplicate these materials before they face irreversible damage.

Cost

Cold storage (freezers) can be costly and prohibitive for many institutions.[2] Digitization can also be costly; factors that need to be considered are size and use of collection, space available for storage, and financial resources.[2]

Deteriorated photographs may require specialized conservation treatment by a professional photograph conservator, often a costly, skill-demanding, and time-consuming procedure. For the majority of photographs in research collections, single-item conservation of deteriorated photographs is probably not a feasible or a cost-effective preservation solution.[11]

Access

Cold storage can be prohibitive for access due to the acclimation periods required to use the film.[2]

Professional conservation and restoration organizations

- American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC)

- Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA)

- Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA)

- Image Permanence Institute (IPI)

- International Council on Archives (ICA)

- International Council of Museums - Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC)

- International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC)

- Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC)

- Society of American Archivists (SAA)

- Visual Materials Association (VRA)

Standards and ethical codes

Standards

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has several standards regarding photography, photographic paper, films, and plates, as well as the safe housing and storage environments of photographic materials including the Photographic Activity Test (PAT).[30]

A sample of some of the ISO standards that relate to film preservation and storage:

- ISO 18902:2013[31] - "Imaging materials - Processed imaging materials - Albums, framing and storage materials"

- ISO 18916:2007[32] - "Imaging materials - Processed imaging materials - Photographic Activity Test for enclosure materials"

- ISO 18911:2010[33] - "Imaging materials - Processed safety photographic films - Storage practices"

- ISO/TR 18931:2001[34] - "Imaging materials - Recommendations for humidity measurement and control"

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) also has a list of technical standards pertaining to the care and handling of photographic materials.

A sample of some of the ANSI standards include:

- ANSI IT9.11-1993[35] - American National Standard for Imaging Media - Processed Safety Photographic Film - Storage

- ANSI IT9.16-1993[35] - American National Standard for Imaging Media - Photographic Activity Test

- ANSI IT9.2-1991[35] - American National Standard for Imaging Media - Photographic Processed Films, Plates, and Papers - Filing Enclosures and Storage Containers,

Codes of ethics

There are several Codes of Ethics for professionals working in conservation and preservation-related fields. The main conservation Code of Ethics is the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC) Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice. However, many of the professional organizations have their own codes, such as the Society of American Archivists Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics.

See also

- Archivist

- Art Conservation and Restoration

- Cellulose acetate film

- Conservation and restoration of photographs

- Nitrocellulose

- Preservation (library and archive)

- Photograph conservator

Further reading

- Lavédrine, Bertrand. Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation. Getty Publications, 2009.

- Lavédrine, Bertrand. A Guide to the Preventive Conservation of Photograph Collections. Getty Publications, 2003.

- Norris, Debra Hess and Jennifer Jae Gutierrez. Issues in the Conservation of Photographs. Getty Publications, 2010.

- Selwitz, Charles. Cellulose Nitrate in Conservation. Getty Publications, 1988.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Valverde, Maria Fernanda (2005). "Photographic Negatives: Nature and Evolution of Process". Image Permanence Institute. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "5.1 A Short Guide to Film Base Photographic Materials: Identification, Care, and Duplication". Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Information Leaflet on the Care, Handling, and Storage of Photographs - Collections Care - Resources |Preservation | Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ^ a b c "Improving Film Storage Conditions" (PDF). National Film Preservation Foundation. 2004. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ "Understanding Film and How It Decays" (PDF). National Film Preservation Foundation. 2004. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Paul, Messier. "Preserving Your Collection of Film-Based Photographic Negatives". cool.conservation-us.org. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- ^ a b "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "Image Permanence Institute | A-D Strips". www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "FilmCare.org". filmcare.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "5.6 Storage Enclosures for Photographic Materials". Northeast Document Conservation Center. Archived from the original on 2017-03-14. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ^ "Care, Handling, and Storage of Motion Picture Film - Collections Care (Preservation, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- ^ "Film Handling and Inspection" (PDF). National Film Preservation Foundation. 2004. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Horvath, David G. (1987). "The Acetate Negative Survey" (PDF). Gawain Weaver Art Conservation. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ "- Photography". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "ISO 18902:2013 - Imaging materials -- Processed imaging materials -- Albums, framing and storage materials". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "ISO 18916:2007 - Imaging materials -- Processed imaging materials -- Photographic activity test for enclosure materials". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "ISO 18911:2010 - Imaging materials -- Processed safety photographic films -- Storage practices". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "ISO/TR 18931:2001 - Imaging materials - Recommendations for humidity measurement and control". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b c Reilly, James M. (1993). "Basic Strategy for Film Preservation". Image Permanence Institute. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

External links

- A Short Guide to Film Based Photographic Materials: Identification, Care and Duplication, Northeast Document Conservation Center Preservation Leaflet 5.1

- Appendix M: Management of Cellulose Nitrate and Cellulose Ester Film, National Park Service

- Care, Handling, and Storage of Photographs, Library of Congress

- Caring for Belongings, The American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works

- Caring for Cellulose Nitrate Film, National Park Service, Conserve O Gram

- Cold Storage, National Park Service

- Cold Storage References, Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts

- filmcare.org, Image Permanence Institute

- Film Preservation Guide: The Basics for Archives, Libraries and Museums, National Film Preservation Foundation

- Identification of Film-Based Photographic Materials, National Park Service, Conserve O Gram

- Photograph Conservation Terminology, Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts

- Storage and Display Materials for Photographs, Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts

- Storage Guide for Acetate Film, Image Permanence Institute

- Storage Enclosures for Photographic Materials, Northeast Document Conservation Center Preservation Leaflet 5.6

- Storing your Photographic Collection: A Guide to Choosing the Proper Materials for Long-term Storage, Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts

- Web Resources for Photograph Identification and Preservation, Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts