Church of the Saintes Maries de la Mer

| Church of the Saintes Maries de la Mer Église de Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer | |

|---|---|

View of Church of the Saintes Maries de la Mer | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Region | Camargue |

| Rite | Latin |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, France |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°27′06″N 4°25′40″E / 43.4516°N 4.4278°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Completed | 9th century |

The Church of the Saintes Maries de la Mer is a Romanesque fortified church built in the 9th century in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in Camargue, Bouches-du-Rhône, Provence. Dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus and to The Three Marys, it is the subject of annual Roma pilgrimage. Since 1840, it has been classified as a French Historical Monument.[1]

Background

According to writer Jean-Paul Clébert, the Greek geographer and historian Strabo wrote that the Phocaeans of Massalia (modern Marseille) erected a temple to Artemis. The first mention of the town (then an oppidum) is made in the poem Ora Maritima (English:The Sea Coast) by Avienius in the 4th century, under the name of an islet called "oppidum priscium Râ."[2] In the 6th century, this oppidum was renamed, "Sancta Maria de Ratis" (English:Saint Mary of the Raft), a name which evolved into Notre-Dame-de-la-Barque when the Christian legend of the landing of the Three Marys on the Camargue coast became popular.[3] This change was made from 547, with the installation of a community of nuns on this islet by Caesarius of Arles, the Archbishop of Arles,[4] to Christianize this place of pilgrimage and pagan worship to Mithras and Artemis.[5]

-

Aerial view of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

-

Panoramic view of Stes-Marie-de-la-Mer from the east

-

Tableau of the Three Marys

From Notre-Dame-de-la-Barque to Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer

The fortified church sits in a prominent place and is visible from around 10 kilometres (6.2 mi). The church's bell-gable has dominated the town since its construction in the beginning of the 9th century. It offered protection to the town during the period of transitions between the Carolingian Empire, the Vikings and Saracens,[6] and the founding of feudalism and its fortified churches and fortified castles to offer protection. The construction of the church spanned the transitions between Carolingian architecture and Romanesque architecture in the Middle Ages.

-

Keep-apse-bell tower-wall

-

Keep-apse-bell tower-wall

-

Keep-apse-bell tower-wall and side view

-

Roof and bell tower

-

Side view, and steeple-wall

-

Facade and corner tower

-

Entrance and croix camarguaise

The site of Notre-Dame-de-la-Barque had been under constant threat from Saracens and Vikings, which forced the nuns to abandon it. It was not until 973 that the Saracens were driven out by Count William I of Provence, who had the church rebuilt (said to be in ruins again in 1061[4]). It passed into the mense of the metropolitan chapter of the Church of St. Trophime in Arles, then the canons returned it to the Montmajour Abbey, which established a priory there in 1078. It was then that it was dedicated to Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer.[7] The reconstruction of the current fortified church took place between 1165 and 1170[8] (at the beginning of the 12th century in Gothic style, with architectural similarities with the 13th century Gothic Papal Palace in Avignon).[9]

-

View from the Mediterranean Sea

-

View from the roof battlements

The church was then divided into three parts, "savoir une nef, une chapelle assez allongée fermée sur le devant par une grille de fer, et sur les deux côtés et le fond par un mur de pierres de taille; un chœur au centre, réservé aux clercs. On a accès à celui-ci par un long couloir formé par un mur latéral de ladite chapelle. (English: "namely a nave, a rather elongated chapel closed on the front by an iron gate, and on both sides and the bottom by a wall of freestone; a choir in the center, reserved for clerics. We have access to it by a long corridor formed by a side wall of the said chapel.)"[10]

In the 14th century, during the pontificate of the Popes of Avignon, the "Pilgrimage to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer" was popular. So much so that in 1343, Benedict XII fixed the celebration of the Saints on May 25 and October 22.[9] Jean de Venette, author of a poem on the "History of the Three Marys," says that he visited Pierre de Nantes, bishop of Saint-Pol-de-Léon, then suffering from gout, and that the latter was healing only through the intercession of the Three Marys. The bishop then made a pilgrimage to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in 1357.[11] That same year, Arnaud de Cervole, known as the Archpriest, headed for Avignon via the Camargue with his Anglo-Gascon bands. The relics contained in the church were sheltered at Sainte-Baume and Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer saw its fortifications reinforced.[4]

Early church

Archaeological excavations have found that the structures of the church that preceded Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer was a rural chapel with a single nave. This place of worship was built in hard limestone.[7] The nave of this primitive church consisted of three bays which led to a choir closed by a semicircular apse. It was flanked, to the north, by a square tower which was accessible by a staircase leading from the choir.[7]

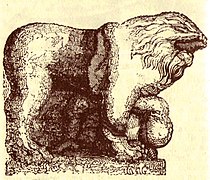

Two doors gave access to the church by the side facades. The first, in the North, was reserved for clergy. It provided access to the cloister and the garden. The second opened into the third southern bay. This door was decorated by two lions of the Arles type which are currently repurposed on a 15th-century walled door.[7] The apse was preceded by a chancel bay and a high triumphal arch.[12]

-

Lion of the Arles type that belonged to the early church, 19th century engraving

-

Lions from the early church in reuse on a 15th-century door

The excavations of King René

In 1448, many relics were found during the reign of René of Anjou.[5] The entire floor of the church was excavated, uncovering a well and a source of fresh water. In the choir, "une petite grotte renfermant des écuelles en terre, les unes entières, les autres brisées, et une certaine quantité de cendres avec des charbons noir (English: a small cave was uncovered containing earthen bowls, some whole, others broken, and a certain quantity of ashes with black coals).[10] Finally, between this cave and the wall of the 12th century chapel, a vestige of the wall was revealed which spanned the entire choir. It opened with a small door giving access to an oratory. In it was a column supporting a marble table forming an altar.[10]

Two bodies "giving off a sweet smell" were also found, and were identified as Mary Jacobe and Mary Salome.[10] The bones, washed with white wine, were placed in reliquaries and transported to the upper chapel.[9][10] At the end of the excavations, three cippi were exhumed and were named, as was smooth piece of marble, "the pillows of the Saints." Still visible in the crypt of the church, the first two are dedicated to Juno and the third is a taurobolium having been used for the worship of Mithras. [10] Jean-Paul Clébert suggests that the cult of the Three Marys (the Tremaie) replaced an ancient cult given to the Matres, Celtic deities of fertility, and which had been Romanized under the name of Juno.[3]

The discovery of the relics attributed to the Three Marys was accompanied by the decision to venerate them three times a year, on May 25, for the feast of Mary Jacobe, on October 22 for that of Mary Salome and December 3. A procession to the sea, with the boat and the two saints, takes place in May and October. Saint Sarah is venerated on May 24.[5]

Jean-Paul Clébert points out that the statue of Sarah as well as that of Three Marys in their boat are headless and have a removable head. He notes, "Les "Mères", qui avaient pris tant de soins d'apporter en exil quatre têtes sacrées, semblent avoir perdu les leurs au cours des vicissitudes de leur histoire," (English:The "Mothers", who had taken so much care to bring four sacred heads into exile, seem to have lost theirs during the vicissitudes of their history)[13]

The procession to the sea

Fernand Benoit, who was the first historian to study the folklore of the Three Marys and Saint Sarah, notes the importance of the Roma procession to the sea. Since 1936, the immersion of Sarah, the black saint, which the Romani people have done, precedes by one day that of the Marys in their boat. The statue of Sarah is submerged up to the waist.[14]

In the Camargue, ritual immersion in the sea follows a centuries-old tradition. Already in the 17th century, the Camarguais people went through the woods and vineyards to the beach, then several kilometers away from the church, and bowed on their knees in the sea.[14]

Le rite de la navigation du "char naval," dépouillé de la légende du débarquement, apparaît comme une cérémonie complexe qui unit procession du char à travers la campagne et pratique de l'immersion des reliques, il se rattache aux processions agraires et purificatrices qui nous ont été conservées par les fêtes des Rogations et du Carnaval

The rite of the navigation of the "naval chariot," stripped of the legend of the landing, appears as a complex ceremony which unites procession of the chariot through the countryside and the practice of immersing the relics, it is linked to the agrarian and purifying processions which have been preserved to us by the festivals of Rogations and Carnival— Fernand Benoit, La Provence et le Comtat Venaissin, Arts et traditions populaires.[15]

Benoit, to emphasize that these processions to the sea demonstrate Provençal culture and its respect of the Mediterranean since processions (linked to other saints) are found in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and in Fréjus, Monaco, Saint-Tropez and Collioure.[16]

Current church

Exterior

The village was protected by its medieval ramparts until the French Revolution. The site was one of the main components of the defense of the city of Arles. In its center the church was fortified when needed. Its current appearance dates from the 14th century.[7] The region regularly underwent raids by Barbary pirates, so at the beginning of its construction, the choice of a form of fortress was quickly taken, with a single nave, alternating machicolations, battlements and watchtower, overlooking the city from a height of 15 meters (49 ft).[17]

The exterior apse

The military-style features often conceal the Romanesque construction. Only the polygonal apse is visible from the outside. It is surmounted by an old guardhouse [18] Surrounded by a bay of centring, its two small columns are surmounted by capitals dated to the beginning of the 13th century. It is decorated with Lombard bands that alternate with corbels.[8]

The bell tower and the upper chapel

Overlooking the choir, and over the entire width of the church, the bell tower wall is topped by machicolations and indentations: four in a row, each holding a bell, a fifth above, totally empty. This wall ends by the guardhouse, which enhances the apse.[18] The construction of the nave, in the 14th century and 15th century brought significant changes to the church. The most significant was the construction of a wall walk. Built in acorbel arch, it rests on consoles or buttresses. A high chapel completes up the apse.[8] Located above the choir, in the old guardhouse, it is dedicated to Saint Michael the archangel. It contains the relics of the saints, locked in a chasse and is only brought out for the Pilgrimage to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.[18] Its uniqueness lies in the fact that it has been integrated into the defensive system of the church. It looks like a keep and also served as a lookout post.[8]

Church bells

The bell-gable has five bells:

- Marie Jacobé-Marie Salomé, cast in 1993 by the Fonderie Paccard in Annecy, note: G

- Claire, cast in 1837 by Eugène Baudouin in Marseille, note: A♯

- Rosa, cast in 1839 by Eugène Baudouin in Marseille, note: C

- Réconciliation, cast in 1984 by the Fonderie Paccard in Annecy, note: D

- Fulcranne, cast in Pierre Pierron in Avignon, note: D#

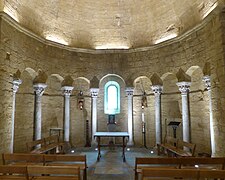

Interior

The Romanesque style church consists of a nave, four bays and a semi-circular apse. The simplicity of the building stands out in its interior decoration. Only a crypt, dedicated to Saint Sarah and an "Upper Chapel," dedicated to Saint Michael, in the old room of the guardhouse, complete the rectangular nave and the 'semicircular' apse.[18]

The church has no side chapel and has little decoration, apart from a niche, on the left, with a representation of Mary of Clopas and Mary Salome, in a boat. This single nave, in a broken cradle, is supported laterally only by full vaults, with arches, contained in the wide thicknesses of the walls.[19] The presence of a well, under the 17th century wooden Christ, harkens back to when the fortified church served as a shelter for the population during pirate invasions in the Middle Ages.[18] North side of the nave, close to the entrance portal, is also visible part of the original paving, as well as a holy water font, dug in an old capital.[19]

Among the rare decorations of the nave, there are two objects classified as historical artifacts since 1840: a retable, in gilded wood, dating from the 17th century,[20] and a painted altar canopy, on a dais, from the 16th century, representing the Apostles and the Nativity.[21]

-

The Three Marys, in a boat and surrounded by votive offerings

Interior apse

The apse was built in the shape of a semi-dome and has seven blind arcades supported by eight marble columns topped with historiated (or figured) capitals. They are subdivided into two groups.[8] The first is made up of six capitals decorated with foliage, masks and human busts or devil's heads. Their style makes them similar to those of the north gallery of the Cloister of Saint-Trophime . These sculptures were placed between 1160 and 1165.[8]

The second group has only two capitals. These are considered major masterpieces of Romanesque architecture of Provence. The first represents the Incarnation of Christ, the second the Passion of Christ. Dated from the same period as the older ones, their style relates to those of the frieze of the Cathedral of Nîmes.[8]

-

Holy water font carved in an old capital

The Mystery of the Incarnation stages on one side the theme of the Visitation and on the other the appearance of the Archangel Gabriel to Zechariah. The Passion of Christ, meanwhile, is evoked in the form of the Sacrifice of Abraham.[8]

The crypt

The crypt is located under the church choir, and can be accessed from the transept. The crypt is dedicated to Saint Sarah, who is represented by a clothed statue, and has its own altar, and many ex-votos. In 1448, the crypt was dug at the direction of René of Anjou, then in search of the relics of the "Three Marys." A perfectly smooth block of marble, the "Pillow of the Three Marys," was also discovered during this excavation.[19]

-

Crypt entrance

-

Saint Sarah

-

Saint Sarah

-

Altar in the crypt

-

Pillow of the Three Marys

See also

References

- ^ Base Mérimée: Église Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Clébert 1972, p. 420.

- ^ a b Clébert 1972, p. 421.

- ^ a b c Mélot 1970, p. 715.

- ^ a b c Bordigoni 2002, p. 489.

- ^ "Vicedi en Camargue". vicedi.com. October 25, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2019..

- ^ a b c d e Rouquette 1974, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rouquette 1974, p. 53.

- ^ a b c "Pèlerinage gitan et le marquis de Baroncelli" [Roma pilgrimage and the Marquis de Baroncelli] (in French).

- ^ a b c d e f Clébert 1972, p. 423.

- ^ de La Curne, M. (1736). Mémoire concernant la vie de Jean de Venette, avec la Notice de l'Histoire en vers des Trois Maries, dont il est auteur.

- ^ Rouquette 1974, p. 523.

- ^ Clébert 1972, p. 427.

- ^ a b Benoit 1992, p. 253.

- ^ Benoit 1992, p. 253-254.

- ^ Benoit 1992, p. 250-252.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église" [History of the church]. Office de Tourisme des Saintes-Maries de la Mer – Tourisme en Camargue. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Guitteny 2011, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Saletta 2017, p. 417.

- ^ Palissy

- ^ Palissy

Bibliography

- Benoit, Fernand [in French] (1992). La Provence et le Comtat Venaissin, Atrs et traditions populaires. Avignon: Aubanel. ISBN 2700600614.

- Bordigoni, Marc (2002). Le Pèlerinage des Gitans, entre foi, tradition et tourisme (in French). Aix-en-Provence: Institut d’ethnologie méditerranéenne et comparative.

- Clébert, Jean-Paul (1972). Guide de la Provence mystérieuse (in French). Paris: Tchou.

- Guitteny, Marc (2011). Camargue (in French). Monaco: AJAX. ISBN 978-2844731876.

- Rouquette, Jean-Maurice (1974). Provence Romane 1 (in French). Vol. 1. Zodiaque.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Mélot, Michel (1970). Guide de la mer mystérieuse. Paris: Tchou.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Saletta, Patrick (2017). Provence Côte d'Azur (Les carnets du patrimoine) (in French). Charles Massin. ISBN 978-2707204097.