Chinoiserie

Chinoiserie (English: /ʃɪnˈwɑːzəri/, French: [ʃinwazʁi]; loanword from French chinoiserie, from chinois, "Chinese"; traditional Chinese: 中國風; simplified Chinese: 中国风; pinyin: Zhōngguófēng; lit. 'China style') is the European interpretation and imitation of Chinese and other East Asian artistic traditions, especially in the decorative arts, garden design, architecture, literature, theatre, and music.[1] The aesthetic of chinoiserie has been expressed in different ways depending on the region. It is related to the broader current of Orientalism, which studied Far East cultures from a historical, philological, anthropological, philosophical, and religious point of view. First appearing in the 17th century, this trend was popularized in the 18th century due to the rise in trade with China (during the High Qing era) and the rest of East Asia.[2]

As a style, chinoiserie is related to the Rococo style.[3] Both styles are characterized by exuberant decoration, asymmetry, a focus on materials, and stylized nature and subject matter that focuses on leisure and pleasure. Chinoiserie focuses on subjects that were thought by Europeans to be typical of Chinese culture.

History

Chinoiserie entered European art and decoration in the mid-to-late 17th century; the work of Athanasius Kircher influenced the study of Orientalism. The popularity of chinoiserie peaked around the middle of the 18th century when it was associated with the Rococo style and with works by François Boucher, Thomas Chippendale, and Jean-Baptist Pillement. It was also popularized by the influx of Chinese and Indian goods brought annually to Europe aboard English, Dutch, French, and Swedish East India Companies. There was a revival of popularity for chinoiserie in Europe and the United States from the mid-19th century through the 1920s, and today in elite interior design and fashion.

Though usually understood as a European style, chinoiserie was a global phenomenon. Local versions of chinoiserie were developed in India, Japan, Iran, and particularly Latin America. Through the Manila galleon trade, Spanish traders brought large amounts of Chinese porcelain, lacquer, textiles, and spices from Chinese merchants based in Manila to New Spanish markets in Acapulco, Panama, and Lima. Those products then inspired local artists and artisans such as ceramicists making Talavera pottery at Puebla de Los Angeles.[5]

Chinoiserie had some parallel in "occidenterie",[6] which was Western styled goods produced in 18th century China for Chinese consumers. Although this was a notable interest of the Kangxi Emperor and Qianlong Emperor, as shown by the architecture of Xiyang Lou, it was not restricted only to the court. "Occidenterie" artifacts and art were accessible to a wider variety of consumers, as they were domestically produced.[7]

Popularization

There were many reasons why chinoiserie gained such popularity in Europe in the 18th century. Europeans had a fascination with Asia due to their increased, but still restricted, access to new cultures through expanded trade with East Asia, especially China. The 'China' indicated in the term 'chinoiserie' represented in European people's mind a wider region of the globe that could embrace China itself, but also Japan, Korea, South-East Asia, India or even Persia. In art, the style of "the Orient" was considered a source of inspiration; the atmosphere rich in images and the harmonic designs of the oriental style reflected the picture of an ideal world, from which to draw ideas in order to reshape one's own culture. For this reason the style of chinoiserie is to be regarded as an important result of the exchange between the West and the East. During the 19th century, and especially in its latter period, the style of chinoiserie was assimilated under the generic definition of exoticism.[8]

Even though the root of the word 'chinoiserie' is 'Chine' (China), the Europeans of the 17th and 18th centuries did not have a clear conceptualization of how China was in reality. Often terms like 'Orient', 'Far East' or 'China' were all equally used to signify the region of Eastern Asia that had proper Chinese culture as a major representative, but the meaning of the term could change according to different contexts. Sir William Chambers for example, in his oeuvre A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening of 1772, generically addresses China as the 'Orient'.[8] In the financial records of Louis XIV during the 17th and 18th centuries were already registered expressions like 'façon de la Chine', Chinese manner, or 'à la chinoise', made in the Chinese way. In the 19th century the term 'chinoiserie' appeared for the first time in French literature. In the novel L'Interdiction published in 1836, Honoré de Balzac used chinoiserie to refer to the craftworks made in the Chinese style. From this moment on the term gained momentum and started being used more frequently to mean objects produced in the Chinese style but sometimes also to indicate graceful objects of small dimension or of scarce account. In 1878 'chinoiserie' entered formally in the Dictionnaire de l'Académie.[8]

After the spread of Marco Polo's narrations, the knowledge of China held by the Europeans continued to derive essentially from reports made by merchants and diplomatic envoys. Dating from the latter half of the 17th century a relevant role in this exchange of information was then taken up by the Jesuits, whose continual gathering of missionary intelligence and language transcription gave the European public a new deeper insight of the Chinese empire and its culture.[10]

While Europeans frequently held inaccurate ideas about East Asia, this did not necessarily preclude their fascination and respect. In particular, the Chinese who had "exquisitely finished art... [and] whose court ceremonial was even more elaborate than that of Versailles" were viewed as highly civilized.[11] According to Voltaire in his Art de la Chine, "The fact remains that four thousand years ago, when we did not know how to read, they [the Chinese] knew everything essentially useful of which we boast today."[12] Moreover, Indian philosophy was increasingly admired by philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer, who regarded the Upanishads as the "production of the highest human wisdom" and "the most profitable and elevating reading which...is possible in the world."[13]

Chinoiserie was not universally popular. Some critics saw the style as "…a retreat from reason and taste and a descent into a morally ambiguous world based on hedonism, sensation and values perceived to be feminine."[2] It was viewed as lacking the logic and reason upon which Antique art had been founded. Architect and author Robert Morris claimed that it "…consisted of mere whims and chimera, without rules or order, it requires no fertility of genius to put into execution."[2] Those with a more archaeological view of the East, considered the chinoiserie style, with its distortions and whimsical approach, to be a mockery of the actual Chinese art and architecture.[2] Finally, still others believed that an interest in chinoiserie indicated a pervading "cultural confusion" in European society.[14]

Persistence after the 18th century

Chinoiserie persisted into the 19th and 20th centuries but declined in popularity. There was a notable loss of interest in Chinese-inspired décor after the death in 1830 of King George IV, a great proponent of the style. The First Opium War of 1839–1842 between Britain and China disrupted trade and caused a further decline of interest in the Oriental.[15] China closed its doors to exports and imports and for many people chinoiserie became a fashion of the past.

As British-Chinese relations stabilized towards the end of the 19th century, there was a revival of interest in chinoiserie. Prince Albert, for example, reallocated many chinoiserie works from George IV's Royal Pavilion at Brighton to the more accessible Buckingham Palace. Chinoiserie served to remind Britain of its former colonial glory that was rapidly fading with the modern era.[2]

-

Cuboid vase; circa 1870; bone china; 20.8 × 10.2 × 10 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Pair of round and flat bodied bottles; 1870-1880; porcelain; first bottle: 26.4 × 21 × 10.6 cm, second bottle: 25.7 × 20.2 × 10.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Wall clock; circa 1880; bronze and enamel; probably made by Escalier de Cristal (Paris); Art Institute of Chicago (US)

-

Wallpaper in the chinoiserie style, with a picture frame as its central motif, Rex Whistler

Chinese porcelain

From the Renaissance to the 18th century Western designers attempted to imitate the technical sophistication of Chinese export porcelain (and for that matter Japanese export porcelain – Europeans were generally vague as the origin of "oriental" imports), with only partial success. One of the earliest successful attempts, for instance, was the Medici porcelain manufactured in Florence during the late-16th century, as the Casino of San Marco remained open from 1575 to 1587.[16] Despite never being commercial in nature, the next major attempt to replicate Chinese porcelain was the soft-paste manufactory at Rouen in 1673, with Edme Poterat, widely reputed as creator of the French soft-paste pottery tradition, opening his own factory in 1647.[17] Efforts were eventually made to imitate hard-paste porcelain, which were held in high regard. As such, the direct imitation of Chinese designs in faience began in the late 17th century, was carried into European porcelain production, most naturally in tea wares, and peaked in the wave of rococo chinoiserie (c. 1740–1770).[18]

Earliest hints of chinoiserie appear in the early 17th century, in the arts of the nations with active East India Companies, Holland and England, then by the mid-17th century, in Portugal as well. Tin-glazed pottery (see delftware) made at Delft and other Dutch towns adopted genuine blue-and-white Ming decoration from the early 17th century. After a book by Johan Nieuhof was published the 150 pictures encouraged chinoiserie, and became especially popular in the 18th century. Early ceramic wares in Meissen porcelain and other factories naturally imitated Chinese designs, though the shapes for "useful wares", table and tea wares, typically remained Western, often based on shapes in silver. Decorative wares such as vases followed Chinese shapes.

-

A Medici porcelain bottle; 1575–1587; Louvre. The Casino of San Marco's porcelain manufactory was one of the oldest successful attempts to imitate Chinese porcelain in European history.[16]

-

Austrian coffeepot; circa 1720; hard-paste porcelain; 17.8 × 15.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Covered vases; circa 1770; soft-paste porcelain; height: 38.7 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Dish with a Chinoiserie design. Porcelain decorated in overglaze enamels. 1735–1740 CE. From Jingdezhen, China; possibly decorated in Canton (Guangzhou). Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Painting

The ideas of the decorative and pictorial arts of the East permeated the European and American arts and craft scene. For example, in the United States, "by the mid-18th century, Charleston had imported an impressive array of Asian export luxury goods [such as]...paintings."[19] The aspects of Chinese painting that were integrated into European and American visual arts include asymmetrical compositions, lighthearted subject matter and a general sense of capriciousness.[citation needed]

William Alexander (1767–1816), a British painter, illustrator and engraver who travelled to the East Asia and China in the 18th century, was directly influenced by the culture and landscape he saw in the East.[20] He presented an idealized, romanticized depiction of Chinese culture, but he was influenced by "pre-established visual signs."[20] While the chinoiserie landscapes that Alexander depicted accurately reflected the landscape of China, "paradoxically, it is this imitation and repetition of the iconic signs of China that negate the very possibility of authenticity, and render them into stereotypes."[20] The depiction of China and East Asia in European and American painting was dependent on the understanding of the East by Western preconceptions, rather than representations of Eastern culture as it actually was.

Interior design

Various European monarchs, such as Louis XV of France, gave special favor to chinoiserie, as it blended well with the rococo style. Entire rooms, such as those at Château de Chantilly, were painted with chinoiserie compositions, and artists such as Antoine Watteau and others brought expert craftsmanship to the style.[21] Central European palaces like the Castle of Wörlitz or the Castle of Pillnitz all include rooms decorated with Chinese features, while in the palace of Sanssouci at Potsdam features a Dragon House (Das Drachenhaus) and the Chinese House (Das Chinesische Haus).[22] Pleasure pavilions in "Chinese taste" appeared in the formal parterres of late Baroque and Rococo German and Russian palaces, and in tile panels at Aranjuez near Madrid. Chinese Villages were built in the mountainous park of Wilhelmshöhe near Kassel, Germany; in Drottningholm, Sweden and Tsarskoe Selo, Russia. Thomas Chippendale's mahogany tea tables and china cabinets, especially, were embellished with fretwork glazing and railings, c. 1753–70, but sober homages to early Qing scholars' furnishings were also naturalized, as the tang evolved into a mid-Georgian side table and squared slat-back armchairs suited English gentlemen as well as Chinese scholars. Not every adaptation of Chinese design principles falls within mainstream chinoiserie. Chinoiserie media included "japanned" ware imitations of lacquer and painted tin (tôle) ware that imitated japanning, early painted wallpapers in sheets, after engravings by Jean-Baptiste Pillement, and ceramic figurines and table ornaments.

In the 17th and 18th centuries Europeans began to manufacture furniture that imitated Chinese lacquer furniture.[23] It was frequently decorated with ebony and ivory or Chinese motifs such as pagodas. Thomas Chippendale helped to popularize the production of chinoiserie furniture with the publication of his design book The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker's Director: Being a large Collection of the Most Elegant and Useful Designs of Household Furniture, In the Most Fashionable Taste. His designs provided a guide for intricate chinoiserie furniture and its decoration. His chairs and cabinets were often decorated with scenes of colorful birds, flowers, or images of exotic imaginary places. The compositions of this decoration were often asymmetrical.

The increased use of wallpaper in European homes in the 18th century also reflects the general fascination with chinoiserie motifs. With the rise of the villa and a growing taste for sunlit interiors, the popularity of wallpaper grew. The demand for wallpaper created by Chinese artists began first with European aristocrats between 1740 and 1790.[24] The luxurious wallpaper available to them would have been unique, handmade, and expensive.[24] Later wallpaper with chinoiserie motifs became accessible to the middle class when it could be printed and thus produced in a range of grades and prices.[25]

The patterns on chinoiserie wallpaper are similar to the pagodas, floral designs, and exotic imaginary scenes found on chinoiserie furniture and porcelain. Like chinoiserie furniture and other decorative art forms, chinoiserie wallpaper was typically placed in bedrooms, closets, and other private rooms of a house. The patterns on wallpaper were expected to complement the decorative objects and furniture in a room, creating a complementary backdrop.

Architecture and gardens

European understanding of Chinese and East Asian garden design is exemplified by the use of the word Sharawadgi, understood as beauty, without order that takes the form of an aesthetically pleasing irregularity in landscape design. The word traveled together with imported lacquer ware from Japan where shara'aji was an idiom in appraisal of design in decorative arts.[26] Sir William Temple (1628–1699), referring to such artwork, introduces the term sharawadgi in his essay Upon the Gardens of Epicurus written in 1685 and published in 1690.[27] Under Temple's influence European gardeners and landscape designers used the concept of sharawadgi to create gardens that were believed to reflect the asymmetry and naturalism present in the gardens of the East.

These gardens often contain various fragrant plants, flowers and trees, decorative rocks, ponds or lake with fish, and twisting pathways. They are frequently enclosed by a wall. Architectural features placed in these gardens often include pagodas, ceremonial halls used for celebrations or holidays, pavilions with flowers and seasonal elements.[28]

Landscapes such as London's Kew Gardens show distinct Chinese influence in architecture. The monumental 163-foot Great Pagoda in the centre of the gardens, designed and built by William Chambers, exhibits strong English architectural elements, resulting in a product of combined cultures (Bald, 290). A replica of it was built in Munich's Englischer Garten, while the Chinese Garden of Oranienbaum includes another pagoda and also a Chinese teahouse. Though the rise of a more serious approach in Neoclassicism from the 1770s onward tended to replace Oriental inspired designs, at the height of Regency "Grecian" furnishings, the Prince Regent came down with a case of Brighton Pavilion, and Chamberlain's Worcester china manufactory imitated "Imari" wares.[citation needed] While classical styles reigned in the parade rooms, upscale houses, from Badminton House (where the "Chinese Bedroom" was furnished by William and John Linnell, ca 1754) and Nostell Priory to Casa Loma in Toronto, sometimes featured an entire guest room decorated in the chinoiserie style, complete with Chinese-styled bed, phoenix-themed wallpaper, and china. Later exoticism added imaginary Turkish themes, where a "diwan" became a sofa.

Tea

One of the things that contributed to the popularity of chinoiserie was the 18th-century vogue for tea drinking.[29] The feminine and domestic culture of drinking tea required an appropriate chinoiserie mise en scène. According to Beevers, "Tea drinking was a fundamental part of polite society; much of the interest in both Chinese export wares and chinoiserie rose from the desire to create appropriate settings for the ritual of tea drinking."[2] After 1750, England was importing 10 million pounds of tea annually, demonstrating how widespread this practice was.[30] The taste for chinoiserie porcelain, both export wares and European imitations, and tea drinking was more associated with women than men. A number of aristocratic and socially important women were famous collectors of chinoiserie porcelain, among them Queen Mary II, Queen Anne, Henrietta Howard, and the Duchess of Queensbury, all socially important women. This is significant because their homes served as examples of good taste and sociability.[31] A single historical incident in which there was a "keen competition between Margaret, 2nd Duchess of Portland, and Elizabeth, Countess of Ilchester, for a Japanese blue and white plate,"[32] shows how wealthy female consumers asserted their purchasing power and their need to play a role in creating the prevailing vogue.

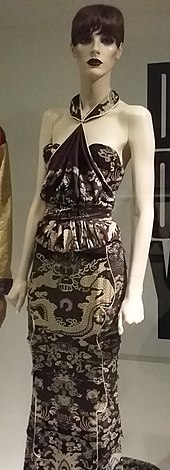

Fashion

The term is also used in the fashion industry to describe "designs in textiles, fashion, and the decorative arts that derive from Chinese styles".[33] Since the 17th century, Chinese arts and aesthetic were sources of inspiration to artists and creators,[34]: 52 and fashion designers when goods from oriental countries were widely seen for the first time in Western Europe.[35]: 546

In the 18th century and throughout the 19th century, chinoiserie fashion was especially celebrated in France, and the origin of most Chinese-inspired fashion was French during this period.[36] Chinoiserie had also inspired designers such as Mariano Fortuny, the Callot Soeurs, and Jean Paquin.[37]: 4

In the early 20th century, European and fashion designers would use China and other countries outside of the Eurocentric-fashion world to seek inspiration; Vogue magazine also acknowledged that China had contributed to the aesthetic inspiration to global fashion.[38] Chinese motifs grew popular in European fashion during this period.[39]: 239 China and the Chinese people also supplied the materials and aesthetics to American fashion.[38] Original Chinese fashion also influenced various designs and styles of deshabille.[40]

There was also a fashion trend for day-wear jackets and coats to be cut in styles which would suggest various Chinese items as was published the Ladies' Home Journal in June 1913, where the garments displayed showed influences of the Qing dynasty mandarin court gown (especially the bufu), the jiaoling ruqun, kanjia, mamianqun, yunjian, yaoqun (short waist-skirt), piling (collar), as well as traditional Chinese embroideries, and traditional Chinese Lào zi, pankou, high collars, etc.[40]

According to the Ladies' Home Journal of June 1913, volume 30, issue 6:

Interest in the political and civic activities of the new China, which is more or less world-wide at this time, led the designers of this page [p.26] and the succeeding one [p.27] to look to that country for inspiration for clothes that would be unique and new and yet fit in with present-day modes and the needs and environments of American women [...]

— Ladies’ Home Journal: The Chinese Summer Dress, published in June 1913: Vol 30, issue 6, p. 26

Music

Western approximations of Chinese music first began to be used in the mid-17th century in operas such as Purcell's The Fairy-Queen (1692) and Gluck's Le cinesi (1754).[41] Jean-Jacques Rousseau included what he claimed was an authentic Chinese melody, the air chinois, in his 1768 Dictionary of Music, and it was re-used by Weber in his Overtura cinesa (1804).[42] Offenbach's satirical one-act operetta Ba-ta-clan (1855) was a big success in Paris.[43]

In the early 20th century French composers responded to the West's then utopian, nostalgic view of Chinese landscape and culture in pieces such as Pagodas (Debussy, 1903).[44] There followed three major 20th century examples of musical chinoiserie: Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (1908), Stravinsky's The Nightingale (1914), and Puccini's Turandot (1926).[45]

Other notable pieces include Tchaikovsky's 'Chinese Dance' (from Act Two of The Nutcracker 1892), Ravel's 'Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes' (from Ma mère l'Oye, 1910), the Chinese Symphony (1914) by Bernard van Dieren, and the light music orchestral fantasy In a Chinese Temple Garden by Albert Ketelbey (1923). In Britain, many 20th century song composers set English translations of Chinese poetry (by orientalists such as Launcelot Cranmer-Byng, Herbert Giles, Edward Powys Mathers and Arthur Waley) to music, including Benjamin Britten in his cycle Songs from the Chinese for high voice and guitar (1957).[46] More recent operatic examples include A Night at the Chinese Opera (Judith Weir, 1987) and Nixon in China (John Adams, 1987).[47]

The influence of Chinese and East Asian music has also been evident in popular music, from musical comedy (A Chinese Honeymoon, 1899), Tin Pan Alley (Limehouse Nights by George Gershwin, 1920), Broadway musicals and jazz (Chinoiserie by Duke Ellington, 1971)[48] through to modern rock music (China Girl by David Bowie, 1976 and many more).[49] These pieces often incorporate Western cultural shorthand clichés of Chinese musical style, such as the oriental riff, making use of the pentatonic scale, often harmonized with open parallel fourths.[50]

Literary criticism

The term is also used in literary criticism. The so-called 'Mandarin style' "is beloved by literary pundits, by those who would make the written word as unlike as possible to the spoken one".[51] Critics also describe a mannered "Chinese-esque" style of writing, such as that employed by Ernest Bramah in his Kai Lung stories, Barry Hughart in his Master Li & Number Ten Ox novels and Stephen Marley in his Chia Black Dragon series.[52]

See also

References and sources

- References

- ^ "Chinois". The Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ a b c d e f Beevers, David (2009). Chinese Whispers: Chinoiserie in Britain, 1650–1930. Brighton: Royal Pavilion & Museums. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-948723-71-1.

- ^ Victoria and Albert Museum, Digital Media. "Style Guide: Chinoiserie". www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Parks, John A. (2015). Universal Principles of ART. Rockport Publishers. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-63159-030-6.

- ^ Carr, Dennis; Bailey, Gauvin A; Brook, Timothy; Codding, Mitchell; Corrigan, Karina; Pierce, Donna (2015-01-01). Made in the Americas: the new world discovers Asia. ISBN 978-0-87846-812-6. OCLC 916494129.

- ^ Yang, Chi-ming (2014). "Eighteenth-Century Easts and Wests: Introduction". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 47 (2): 95–101. doi:10.1353/ecs.2014.0002. ISSN 0013-2586. JSTOR 24690356. S2CID 161177163.

- ^ Kleutghen, Kristina (2014). "Chinese Occidenterie: the Diversity of "Western" Objects in Eighteenth-Century China". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 47 (2): 117–135. doi:10.1353/ecs.2014.0006. ISSN 0013-2586. JSTOR 24690358. S2CID 146268869.

- ^ a b c 張省卿 (Sheng-Ching Chang),《東方啓蒙西方 – 十八世紀德國沃里兹(Wörlitz)自然風景園林之中國元素(Dongfang qimeng Xifang- shiba shiji Deguo Wolizi (Wörlitz) ziran fengjing yuanlin zhi Zhongguo yuansu) 》 (The East enlightening the West – Chinese elements in the 18th century landscape gardens of Wörlitz in Germany), 台北 (Taipei):輔仁大學出版社(Furendaxue chubanshe; Fu Jen University Bookstore), 2015, pp. 37–44.

- ^ "British Museum object". The British Museum.

- ^ 張省卿 (Sheng-Ching Chang),《東方啓蒙西方 – 十八世紀德國沃里兹(Wörlitz)自然風景園林之中國元素(Dongfang qimeng Xifang- shiba shiji Deguo Wolizi (Wörlitz) ziran fengjing yuanlin zhi Zhongguo yuansu) 》 (The East enlightening the West – Chinese elements in the 18th century landscape gardens of Wörlitz in Germany), 台北 (Taipei):輔仁大學出版社(Furendaxue chubanshe; Fu Jen University Bookstore), 2015, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Mayor, A. Hyatt (1941). "Chinoiserie". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 36 (5): 111–114. doi:10.2307/3256573. JSTOR 3256573.

- ^ Voltaire as qtd. in Lovejoy, Arthur. (1948) Essays in the History of Ideas (1948). Johns Hopkins U. Press. 1978 edition: ISBN 0-313-20504-3

- ^ Clarke, J. J. (1997). Oriental enlightenment : the encounter between Asian and Western thought. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-00438-8. OCLC 52219015.

- ^ Lee, Julia H. (2011). Interracial Encounters: Reciprocal Representations in African and Asian American Literatures, 1896–1937. New York: NYU Press. pp. 114–37. ISBN 978-0-8147-5257-9.

- ^ Gelber, Harry G (2004). Opium, Soldiers and Evangelicals: England's 1840–42 War with China and its Aftermath. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-0700-4.

- ^ a b "Medici porcelain". Britannica.com. 2013-07-22. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ "Rouen ware | pottery". The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Britannica.com. 2007. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Key Periods in the Development of Chinoiserie Style in the West – How Taste Travelled. Part I". Decorative Fair. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Leath, R. A.. (1999). "After the Chinese Taste": Chinese Export Porcelain and Chinoiserie Design in Eighteen-Century Charleston. Historical Archaeology, 33(3), 48–61.

- ^ a b c Sloboda, Stacey (2014). Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament in Eighteenth-Century Britain. New York: Manchester UP. pp. 29, 33. ISBN 978-0-7190-8945-9.

- ^ Jan-Erik Nilsson. "chinoiserie". Gothenborg.com. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ^ 張省卿 (Sheng-Ching Chang),《東方啓蒙西方 – 十八世紀德國沃里兹(Wörlitz)自然風景園林之中國元素(Dongfang qimeng Xifang- shiba shiji Deguo Wolizi (Wörlitz) ziran fengjing yuanlin zhi Zhongguo yuansu) 》 (The East enlightening the West – Chinese elements in the 18th century landscape gardens of Wörlitz in Germany), 台北 (Taipei):輔仁大學出版社(Furendaxue chubanshe; Fu Jen University Bookstore), 2015, pp. 44–45.

- ^ "V&A · The influence of East Asian lacquer on European furniture". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ a b Entwistle, E. A. (1961). "Wallpaper and its History". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts: 450–456.

- ^ Vickery, Amanda (2009). Behind Closed Doors. New Haven, CT: Yale UP. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-300-16896-9.

- ^ Kuitert, Wybe (2014). "Japanese Art, Aesthetics, and a European Discourse: Unraveling Sharawadgi". Japan Review. 27: 78.Online as PDF

- ^ William Temple. "Upon the Gardens of Epicurus; or Of Gardening in the Year 1685." In Miscellanea, the Second Part, in Four Essays. Simpson, 1690

- ^ Zhou, Ruru (2015). "Chinese Gardens". China Highlights.

- ^ Godoy, Maria (7 April 2015). "Tea Tuesdays: How Tea + Sugar Reshaped The British Empire". npr.org. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Fisher, Reka N. (1979). "English Tea Caddy". Bulletin (St. Louis Art Museum). 15 (2): 174–175. JSTOR 40716247.

- ^ Porter, David (2002). "Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 35 (3): 395–411. doi:10.1353/ecs.2002.0031. S2CID 161692788.

- ^ Impey, Oliver (1989). "Eastern Trade and the Furnishing of the British Country House". Studies in the History of Art. 25: 177–2. JSTOR 42620694.

- ^ Calasibetta, Charlotte Mankey; Tortora, Phyllis (2010). The Fairchild Dictionary of Fashion (PDF). New York: Fairchild Books. ISBN 978-1-56367-973-5. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ Rovai, Serena (2016). Luxury the Chinese way : new competitive scenarios. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire. ISBN 978-1-137-53775-1. OCLC 946357865.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Berg companion to fashion. Valerie Steele. London. 2018. ISBN 978-1-4742-6471-6. OCLC 1101075054.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "The Chinoiserie Paradox: Fashion Creating the Self Through the "Other" – Compass". Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ Sterlacci, Francesca (2017). Historical dictionary of the fashion industry. Joanne Arbuckle (Second ed.). Landham. ISBN 978-1-4422-3909-8. OCLC 969439606.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Chan, Heather (2017). "From Costume to Fashion: Visions of Chinese Modernity in Vogue Magazine, 1892–1943". Ars Orientalis. 47 (20220203). doi:10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.009. hdl:2027/spo.13441566.0047.009. ISSN 2328-1286.

- ^ Beyond chinoiserie : artistic exchange between China and the West during the late Qing dynasty (1796–1911). Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Jennifer Dawn Milam. Leiden. 2019. ISBN 978-90-04-38783-6. OCLC 1077291584.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "Fashioning Empire: Chinese Chic". BASIS Independent Silicon Valley. 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ Bellman, Jonathan, ed. The Exotic in Western Music (1998)

- ^ The same theme was later used by Eugene Goossens in his Variations on a Chinese Theme (1912) and by Hindemith in the Symphonic Metamorphosis of themes by Carl Maria von Weber (1943)

- ^ Lamb A. Ba-ta-clan. In: The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

- ^ Locke, Ralph. Musical Exoticism (2009)

- ^ Scott, Derek B. 'The Twentieth Century: Orientalism and Musical Style', in Musical Quarterly No. 8212 (1998), pp. 309-35

- ^ There are other settings of Chinese translations by Granville Bantock, Lennox Berkeley, Arthur Bliss, Armstrong Gibbs, Constant Lambert, C.W. Orr, Alan Rawsthorne and Humphrey Searle.

- ^ John Adams has stated: "at no point in this opera did I want to write fake Chinese music". Daines, Matthew. Telling the Truth about Nixon: Parody, Cultural Representation, and Gender Politics in John Adams’s Opera Nixon in China, Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Davis (1995), p. 118

- ^ Moon, Krystyn R. Yellowface: Creating the Chinese in American Popular Music and Performance, 1850s-1920s (2005)

- ^ Chris Eldon Lee (producer). BBC Radio 4 documentary, Chopsticks at Dawn, first broadcast 8 June, 2010

- ^ Steve Inskeep [host] (August 28, 2014). "How The 'Kung Fu Fighting' Melody Came To Represent Asia [transcript]". NPR. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise (1938), ch. 20

- ^ Marley rejects the chinoiserie label in favour of his own term, "Chinese Gothic".

- Sources

- Chang, Sheng-Ching (張省卿),《東方啓蒙西方 – 十八世紀德國沃里兹(Wörlitz)自然風景園林之中國元素(Dongfang qimeng Xifang – shiba shiji Deguo Wolizi (Wörlitz) ziran fengjing yuanlin zhi Zhongguo yuansu) 》 (The East enlightening the West – Chinese elements in the 18th century landscape gardens of Wörlitz in Germany), 台北 (Taipei):輔仁大學出版社 (Furendaxue chubanshe; Fu Jen University Bookstore), 2015.

- Eerdmans, Emily (2006). "The International Court Style: William & Mary and Queen Anne: 1689–1714, The Call of the Orient". Classic English Design and Antiques: Period Styles and Furniture; The Hyde Park Antiques Collection. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-8478-2863-0.

- Honour, Hugh (1961). Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay. London: John Murray.

- Kang, Angela. Musical chinoiserie, University of Nottingham thesis, September 2011

External links

- Chinoiserie in the Columbia Encyclopedia

- (Getty Museum) "Imagining the Orient" exhibition, 2004–05.

- Example of Chinoiserie in a French Style Harpsichord Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine