Charles Norris-Newman

Charles Norris-Newman | |

|---|---|

| Born | 22 August 1852 Elvington Hall, Yorkshire, England |

| Died | May 1920 (aged 67) Victoria Hospital, Tianjin, China |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

Charles Louis Marie William Norris-Newman (22 August 1852 – May 1920) was a British journalist, adventurer and intelligence officer with the Russian Navy. He was present at the 1870–1871 Siege of Paris and was in Spain during the Third Carlist War (from 1872) and in Egypt with General Charles George Gordon.

Norris-Newman was in Southern Africa from 1877 and was the only newspaper correspondent with the British forces during the invasion of Zululand in 1879, reporting for The Standard. He was present at the Action at Sihayo's Kraal, narrowly avoided the massacre of the British at the Battle of Isandlwana and was among the first group to ride into Rorke's Drift after the battle. Norris-Newman took up arms in the Battle of Gingindlovu, was the first to ride into the besieged settlement of Eshowe and was present at the final action, the Battle of Ulundi. He remained in the area after the war and covered the brief First Boer War of 1880–1881, though he was too late to witness any fighting. He afterwards joined Digby Willoughby in Basutoland and Madagascar. In 1885 he was town clerk and treasurer to the municipality of Aliwal North in Cape Colony but was dismissed for embezzlement. Norris-Newman afterwards reported on military campaigns in Central Africa. By the mid-1890s he was with the British South Africa Company in their campaign to take over Matabeleland. He published two newspapers, worked for Reuters and managed a messenger company. He worked for the company as an intelligence officer and colonial official in the Second Matabele War of 1896–1897.

Norris-Newman afterwards spent time in East Asia and in 1900, having fled creditors in China, married a former prostitute in Japan. His wife's former occupation excluded Norris-Newman from polite society. Norris-Newman was abusive to his wife and child, who died young, and she divorced him in 1908. From 1902 Norris-Newman worked for the Imperial Russian Navy first as an English teacher and then in publishing a journal in the Far East, eventually being granted the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He was accused by George Ernest Morrison, political adviser to the Chinese Republic, of propaganda against the Japanese during the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. In later life he worked for newspapers in China.

Early life and career

Norris-Newman was born on 22 August 1852 at Elvington Hall, Yorkshire, England. He was the son of C. Sherwood Newman and the Countess de Rosa Y Robyns.[1] He was educated at Sherborne, Lubeck and Harrow and is also known to have received a military education.[2][1] Historian Ian Knight notes that he is sometimes reported to have served as an officer (several contemporaries refer to him as "captain") in the British Army or one of the colonial forces but found no evidence of service.[3] Norris-Newman was present at the Siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and was decorated for his service during the battle by the city's governor Louis-Jules Trochu. He accompanied Infante Carlos, Duke of Madrid during the Third Carlist War (1872–1876) and was with General Charles George Gordon during his service in Egypt (from 1873).[2] He married Anne Falkner of Farnham in 1874.[1] He filed for bankruptcy in December 1875, whilst he was living on Kennington Park Road in Surrey.[4]

Anglo-Zulu War

Norris-Newman arrived in Southern Africa in 1877.[2] At the outbreak of the Anglo-Zulu War in early 1879 he was the only newspaper correspondent with the British force invading Zululand.[5] The British press showed little interest in the occupation, their war correspondents being pre-occupied with the ongoing Second Anglo-Afghan War.[6] Norris-Newman was contracted as a special correspondent to The Standard but by arrangement his reporting was also made available to the local newspapers the Times of Natal and the Cape Standard and Mail.[2]

Norris-Newman accompanied Lord Chelmsford's principal force, the Centre Column. He attached himself to the 3rd Regiment of the Natal Native Contingent (NNC), a black African force led by white officers and non-commissioned officers.[2] The unit's commander, Rupert la Trobe Lonsdale, gave him the nickname "Noggs", after the character Newman Noggs in Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby.[7] He was the first man with the invading force to cross the Buffalo river into Zululand on 11 January, swimming his horse across at 5:00 am before the military began their crossing by pont.[8][9] Norris-Newman accompanied Chelmsford in observing the first engagement of the war, the 12 January Action at Sihayo's Kraal.[10]

Norris-Newman avoided death in the 22 January Battle of Isandlwana, in which the Centre Column's camp in Zululand was wiped out, as he had accompanied the 3rd NNC and Chelmsford on a reconnaissance expedition that morning.[2] Norris-Newman returned with the reconnaissance party later that day. They bivouacked on the bloody battlefield before heading for the post at Rorke's Drift. Uncertain if the post had fallen to the Zulu attack Norris-Newman was with the first party to approach and enter it, having discovered that the defenders had prevailed.[11] Norris-Newman gathered news of the defence before riding to the telegraph office at Pietermaritzburg, from where he filed a report to The Standard. It reached Cape Town by telegraph from where it had to be carried by ship to Cape Verde where a telegraph line connected to London. The story, the first news of the defeat, appeared in the British press twenty days after the battle.[12] The report established Norris-Newman's name in journalism.[12] The report, including a carefully compiled casualty list, was printed locally in an extra edition of the Natal Times on 24 January, the same day he arrived at Pietermaritzburg.[13]

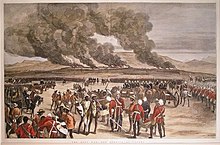

Following the defeat the British press dispatched their best correspondents to Natal, including Melton Prior, Charles Edwin Fripp and Archibald Forbes.[14] The Standard sent F.R. MacKenzie to assist Norris-Newman.[12] Norris-Newman and Forbes returned to Isandhlwana on 20 March with a British party sent to bury some of the dead.[15] Norris-Newman also accompanied the relief expedition for the Siege of Eshowe. During the expedition he was present at the 2 April Battle of Gingindlovu. At one point in that battle he judged the fighting so desperate that he grabbed a rifle and helped, shooting at least one Zulu.[16] After the battle he and a friend, a wagon driver named Palmer, went out into the field and found a group of three dead Zulu that they thought they had killed. They took from them items of their dress and weapons as trophies.[17] Norris-Newman was the first man to enter Eshowe upon its relief, racing the correspondent of the Argus for the honour and beating him by five minutes.[18] Norris-Newman was present in the decisive final British victory of the war, the 4 July Battle of Ulundi.[19]

Norris-Newman's account of the Anglo-Zulu War, On Campaign with the British Army in the Zulu War of 1879, was published in 1880 by W. H. Allen & Co.[20] Zulu War historian Donald R. Morris regarded the book as "brisk and accurate" for the parts of the war that Norris-Newman witnessed but otherwise liable to include hearsay.[21] Norris-Newman featured in the 1979 film Zulu Dawn, portrayed by English actor Ronald Lacey as an "acidic" commentator on the invasion.[22]

Later career in Africa

Norris-Newman was still in Southern Africa when the First Boer War broke out late in 1880 between the British and the Transvaal Boers. He was determined to report the war from the Boer point of view but failed to reach their lines before the ceasefire was declared.[23] Norris-Newman remained to witness the peace negotiations and wrote With the Boers in the Transvaal about his experiences.[23][24]

By 1882 he was in Basutoland, in the wake of the Basuto Gun War, and afterwards joined the adventurer and mercenary Digby Willoughby in Madagascar.[1] Willoughby, who had also served in the Zulu War and Basutoland, was appointed general in the armies of Madagascan queen Ranavalona III which fought the French in the First Franco-Hova War (1883-1885).[25]

By 1885 Norris-Newman was back in Southern Africa, serving as town clerk and treasurer to the municipality of Aliwal North in Cape Colony.[26] He was dismissed after 18 months for embezzlement of town funds.[27] Norris-Newman was then in Zanzibar and Central Africa until 1891, reporting on military campaigns there.[1][2] His reports were published in The Times, the Pall Mall Gazette and the Daily Mail. Norris-Newman also wrote the books The Basuto and their Country and South African Stories.[1]

In the mid-1890s Norris-Newman became associated with the British South Africa Company (BSAC) which was in the process of taking over Matabeleland. By 1894 Norris-Newman was publishing the Matabeleland News and Mining Record with G.R. Cardigan.[28] He was also an agent for the Reuters news service and set up a postal service using a series of runners from Bulawayo southwards to the telegraph line that was being constructed from the Tati Goldfields.[29][30] In 1895 he published Matabeleland And How We Got it on how the BSAC acquired the territory.[31]

By 1896, when he visited England on a sightseeing and lecture tour, Norris-Newman was editor and proprietor of the Rhodesia Weekly Review.[32] During the Second Matabele War of 1896–1897 he served as staff officer to the company's acting administrator.[1] He was also chief intelligence officer to the Bulawayo Field Force and a colonial official.[2][32]

East Asia

Norris-Newman left Africa for East Asia before the turn of the century.[1] He spent time in Ceylon, Malaya, China and Japan.[2] On 14 January 1900 he married Ethel Luke Finch in a Roman Catholic ceremony at Yokohama, Japan. The marriage had not be notified to the registrar so a legal ceremony was held to regularise it the following day at the British consulate.[33] Finch was a former prostitute and Norris-Newman's association with her made it difficult for him to mix in polite society.[2] A contemporary, the Australian political adviser to the Chinese Republic George Ernest Morrison noted that Norris-Newman played on his notoriety, being in the habit of introducing his spouse by telling gentlemen "you have met my wife before I think", implying that they had frequented her brothel.[27]

At the time of his marriage Norris-Newman was in financial difficulty, having fled his creditors in Shanghai. He asked Finch to request money from her father and when she refused began to subject her to physical abuse. Finch delivered their child ahead of term in September 1900, because of the abuse, and it was born with a deformity. Norris-Newman refused to pay for her care during postpartum confinement and she went to stay with her father for 5–6 months. Norris-Newman assaulted Finch again in February 1901 when Finch tried to stop him from dosing their crying and ill child with chlorodyne. In May 1902 Finch and the child left Japan for England on account of their health. Norris-Newman afterwards visited a brothel, telling them to bill his father-in-law.[33]

In 1902 Norris-Newman entered the employ of the Imperial Russian Navy, serving as an English language instructor at Port Arthur where he lived openly with a mistress.[2][1] Norris-Newman's child died in May 1902 and he sent £50 to Finch and asked her to return to him. She travelled to Hong Kong but there received a letter from Norris-Newman telling her to go to her father at Yokohoma. Finch there gathered evidence of Norris-Newman's continuing infidelity, with which she was assisted by members of his family. She applied for a divorce in 1907 and a decree nisi was awarded in 1908 with costs awarded against Norris-Newman.[34][35][33]

Norris-Newman reported as a freelance correspondent from the Russian side of the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War and was witness to the Siege of Port Arthur.[1][2] He founded the China Review in Hankow, the first Russian journal in the Far East.[2] Morrison considered his reports of Japanese shooting down "Chinese on the streets in daylight" and of foreigners in China being under threat of death at Japanese hands as inflammatory and false. He noted they were being translated into Chinese and being printed in the Chinese press. He asked Colonel Alfred W. S. Wingate, in charge of intelligence in North China, to have Norris-Newman arrested by the British consul on charges of endeavouring to create a breach of the peace; it is not clear if this took place.[36] He was during this period granted the rank of lieutenant-colonel by Russia and paid a retainer of $1,000 a month. Morrison noted that despite Norris-Newman's high level of remuneration he was still dissolute, having failed to honour a large number of promissory notes.[27]

Later life

Details of Norris-Newman's later life are little known as he avoided attention, partly on account of his marital issues. By 1907 Norris-Newman was working as an intelligence officer for Russia. By 1910 he was living in Tianjin where he worked for the China Critic and by 1916 was working for the Gazette in Peking.[2]

Norris-Newman's Who's who in the Far East, 1906–7 entry lists a number of decorations: "Madagascar, first class", the Order of the Dannebrog third class, the "French Medal for Valour", the Egypt Medal, the Khedive's Star, the South Africa Medal (1880) and the British South Africa Company Medal. His hobbies were noted as riding, shooting and philately and he is stated to be a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and a Provincial Senior Grand Warden with the freemasons.[1]

Norris-Newman's interest in philately dated from at least his time in Aliwal North and he was elected a member of the Birmingham Philatelic Society in 1896.[37][38] By 1912 he had given an album of 4,000 stamps to a C. H. Meekle to be sold. Meekle passed these stamps to Charles H. Hussman of the Columbia Supply Company in the United States but no money reached Norris-Newman. Hussman claimed the album was security for a loan he had provided. Norris-Newman launched a court case to recover the stamps, or their value which he stated as $1,500. A jury in the court of Julius Muench in March 1912 ordered Hussman to return the album or pay Norris-Newman $750.[39][40] His stamp collection was auctioned on 19 June 1913.[41]

Norris-Newman died of stomach cancer at Victoria Hospital, Tianjin in May 1920.[42][43]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Who's who in the Far East, 1906-7, June. Hongkong, China mail. 1906. p. 251.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Best, Brian (11 November 2016). Fighting for the News: The Adventures of the First War Correspondents from Bonaparte to the Boers. Frontline. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-84832-439-8.

- ^ Knight, Ian (6 May 2011). Zulu Rising: The Epic Story of iSandlwana and Rorke's Drift. Pan Macmillan. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4472-0223-3.

- ^ "No. 24273". The London Gazette. 7 December 1875. p. 6333.

- ^ Gump, James O. (2016). The Dust Rose Like Smoke: The Subjugation of the Zulu and the Sioux, Second Edition. U of Nebraska Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8032-8455-5.

- ^ Greaves, Adrian (19 April 2014). Isandlwana: How the Zulus Humbled the British Empire. Pen and Sword. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-84468-602-5.

- ^ David, Saul (2004). Zulu: The Heroism and Tragedy of the Zulu War. London: Penguin. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-670-91474-6.

- ^ Gillings, Ken (19 October 2014). Discovering the Battlefields of the Anglo-Zulu War. 30 Degrees South Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-928211-18-1.

- ^ Snook, Mike (30 May 2010). How Can Man Die Better: The Secrets of Isandlwana Revealed. Frontline Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4738-1535-3.

- ^ Peers, Chris (30 March 2021). Rorke's Drift and Isandlwana: 22nd January 1879: Minute by Minute. Greenhill Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-78438-537-8.

- ^ Snook, Mike (2010). Like Wolves on the Fold : the Defence of Rorke's Drift. London: Frontline Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-84832-602-6.

- ^ a b c Best, Brian (11 November 2016). Fighting for the News: The Adventures of the First War Correspondents from Bonaparte to the Boers. Frontline. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-84832-439-8.

- ^ Morris, Donald R. (1965). The Washing of the Spears. Pen and Sword. p. 435. ISBN 067-1-63108-X.

- ^ Knight, Ian (21 March 2011). Voices from the Zulu War. Pen and Sword. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-4738-2033-3.

- ^ Snook, Colonel Mike (2010). How Can Man Die Better: The Secrets of Isandlwana Revealed. Frontline Books. p. 282. ISBN 9781473815353. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Manning, Stephen (20 June 2022). Britain Against the Xhosa and Zulu Peoples: Lord Chelmsford's South African Campaigns. Pen and Sword Military. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-3990-1057-3.

- ^ Knight, Ian (16 October 2008). Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War. Pen and Sword. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-84415-801-0.

- ^ David, Saul (2004). Zulu: The Heroism and Tragedy of the Zulu War. London: Penguin. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-670-91474-6.

- ^ Greaves, Adrian (2005). Crossing the Buffalo: The Zulu War of 1879. London: Cassell. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-3043-6725-2.

- ^ Norris-Newman, Charles (April 2013). On Campaign with the British Army in the Zulu War of 1879 - the Illustrated Edition. Archive Media Publishing, Limited. ISBN 978-1-78158-326-5.

- ^ Morris, Donald R. (1965). The Washing of the Spears. Pen and Sword. p. 620. ISBN 067-1-63108-X.

- ^ Stewart, Ian; Carruthers, Susan Lisa (1996). War, Culture, and the Media: Representations of the Military in 20th Century Britain. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8386-3702-9.

- ^ a b Laband, John (10 July 2014). The Transvaal Rebellion: The First Boer War, 1880-1881. Routledge. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-317-86846-0.

- ^ Kwasniewska, Laura (28 August 2018). Bloody-Minded Pigott. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-78901-436-5.

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Office, Great Britain Colonial (1885). Transvaal: Further Correspondence Respecting the Affairs of the Transvaal & Adjacent Territories...Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty... G.E.B. Eyre & W. Spottiswoode. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Morrison, George Ernest (4 March 1976). The Correspondence of G. E. Morrison 1895-12. Cambridge University Press. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-0-521-20486-6.

- ^ "The Talk of Bristol". Bristol Mercury. 24 August 1894. p. 8.

- ^ African Research & Documentation. African Studies Association of the UK. 1984. p. 36.

- ^ Baxter, T. W.; Turner, Robert William Septimus (1966). Rhodesian Epic. H. Timmins. p. 156.

- ^ Norris-Newman, Charles L. (1895). Matabeleland And How We Got it: With Notes on the Occupation of Mashunaland, and an Account of the 1893 Campaign by the British South Africa Company, the Adjoining British Territories and Protectorates. T. Fisher Unwin.

- ^ a b African Review. African Review Publishing Company. 1896. p. 337.

- ^ a b c "Norris-Newman V. Norris-Newman". London and China Telegraph. 4 May 1908. p. 388.

- ^ "Divorce Court File: 7427. Appellant: Ethel Luke Norris-Newman. Respondent: Charles Louis..." National Archives. 1907. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ "Untitled". The Guardian. 1 May 1908. p. 4.

- ^ Morrison, George Ernest (4 March 1976). The Correspondence of G. E. Morrison 1895-12. Cambridge University Press. pp. 93, 292–293. ISBN 978-0-521-20486-6.

- ^ The London Philatelist. Royal Philatelic Society. 1893. p. 72.

- ^ The American Journal of Philately. Scott Stamp and Coin Company. 1896. p. 182.

- ^ "Jury Orders Return of Stamps". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 17 October 1912. p. 11.

- ^ "Berlangt Briefmarten". Westliche Post. 16 March 1912. p. 10.

- ^ Philatelic Literature Review. American Philatelic Research Library. 2003. p. 342.

- ^ "Peking and Tientsin". London and China Telegraph. 21 June 1920. p. 435.

- ^ "Social and Personal". Straits Times. 13 May 1920. p. 6.