Carpet page

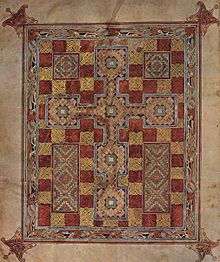

A carpet page is a full page in an illuminated manuscript containing intricate, non-figurative, patterned designs.[1] They are a characteristic feature of Insular manuscripts, and typically placed at the beginning of a Gospel Book. Carpet pages are characterised by mainly geometrical ornamentation which may include repeated animal forms. They are distinct from pages devoted to highly decorated historiated initials, though the style of decoration may be very similar.[2]

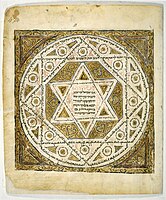

Carpet pages are characterised by ornamentation with brilliant colors, active lines and complex patterns of interlace. They are normally symmetrical, or very nearly so, about both a horizontal and vertical axis, though for example the pictured page from the Lindisfarne Gospels is only symmetrical about a vertical axis. Some art historians find their origin in similar Coptic decorative book pages,[3] and they also clearly borrow from contemporary metalwork decoration. Oriental carpets, or other textiles, may themselves have been influences. The tooled leather book binding of the St Cuthbert Gospel represents a simple carpet page in another medium,[4] and the few surviving treasure bindings – metalwork book covers or book shrines – from the same period, such as that on the Lindau Gospels, are also close parallels.[5] Roman floor mosaics seen in post-Roman Britain, are also cited as a possible source.[6] The Hebrew Codex Cairensis, from 9th century Galilee, also contains a similar type of page, but stylistically very different.

Examples

The earliest surviving example is from the early 7th-century Bobbio Orosius, and relates more closely to Late Antique decoration. There are notable carpet pages in the Book of Kells, the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Book of Durrow, and other manuscripts.[7]

Carpet pages are also found in some medieval Hebrew manuscripts, typically opening the major sections of the book. Islamic manuscripts, especially Qur'ans, often have pages entirely devoted to complex geometrical decoration, but the term is not usually used of them.

Gallery

-

Early insular example from the Book of Durrow

-

Carpet page from the Book of Kells

-

Page from a Qur'an manuscript, 1182

-

Page from a Qur'an manuscript, c. 1370

-

Page from a Qur'an by Ibn al-Bawwab, 1001 AD

-

Carpet page from the Leningrad Codex

References

Notes

Sources

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Moss, Rachel. The Book of Durrow. Dublin: Trinity College Library; London: Thames and Hudson, 2018. ISBN 978-0-5002-9460-4

Further reading

- Alexander, J.J.G. A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles: Volume One: Insular Manuscripts from the 6th to the 9th Century. London England: Harvey Miller. 1978.

- Brown, Michelle P. Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms. Malibu, California: The J. Paul Getty Museum. 1994.

- Laing, Lloyd and Jennifer. Art of the Celts: From 700 BC to the Celtic Revival. Singapore: Thames and Hudson. 1992.

- Megaw, Ruth and Vincent. Celtic Art: From its Beginnings to the Book of Kells. New York: Thames and Hudson. 2001.

- Nordenfalk, Carl. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book Illumination in the British Isles. 600-800. New York: George Braziller Publishing. 1977.

- Pacht, Otto. Book Illumination in the Middle Ages. England: Harvey Miller Publishers. 1984.

- Tilghman, Benjamin C. (2017). "Pattern, Process, and the Creation of Meaning in the Lindisfarne Gospels". West 86th. 24 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1086/693796.

External links

- Treasures of early Irish art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.: from the collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Royal Irish Academy, Trinity College, Dublin, an exhibition catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on carpet pages

- "Sultan Barquq's Qur'an". British Library.

- Howie, Elizabeth. "Dublin, Trinity College MS A.4.5 (57) — Gospel Book (Book of Durrow)". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017.

- "Leningrad Carpet Page". West Semitic Research Project. Archived from the original on 2010-11-26.