Bereshit (parashah)

Bereshit, Bereishit, Bereshis, Bereishis, or B'reshith (בְּרֵאשִׁית—Hebrew for "in beginning" or "in the beginning," the first word in the parashah) is the first weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. The parashah consists of Genesis 1:1–6:8.

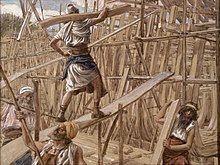

In the parashah, God creates the heavens, the world, Adam and Eve, and Sabbath. A serpent convinces Eve, who then invites Adam, to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which God had forbidden to them. God curses the ground for their sake and expels them from the Garden of Eden. One of their sons, Cain, becomes the first murderer, killing his brother Abel out of jealousy. Adam and Eve have other children, whose descendants populate the Earth. Each generation becomes more and more degenerate until God decides to destroy humanity. Only one person, Noah, finds God's favor.

The parashah is made up of 7,235 Hebrew letters, 1,931 Hebrew words, 146 verses, and 241 lines in a Torah Scroll (Sefer Torah).[1] Jews read it on the first Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in October, or rarely, in late September or early November.[2] Jews also read the beginning part of the parashah, Genesis 1:1–2:3, as the second Torah reading for Simchat Torah, after reading the last parts of the Book of Deuteronomy, Parashat V'Zot HaBerachah, Deuteronomy 33:1–34:12.[3]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In a Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Bereishit has ten "open portion" (פתוחות, petuḥot) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (pe)). Parashat Bereshit has several further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (סְתוּמוֹת, setumot) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the open portion divisions. The first seven open portion divisions set apart the accounts of the first seven days in the first reading. The eighth open portion spans the second and third readings. The ninth open portion contains the fourth, fifth, sixth, and part of the seventh readings. The tenth open portion is identical to the maftir (concluding reading, מפטיר). Closed portion divisions further divide the third, fourth, sixth, and seventh readings.[4]

First reading—Genesis 1:1–2:3

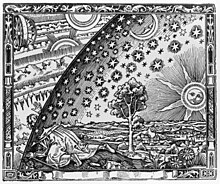

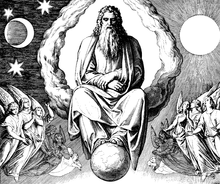

The first reading reports God's creation of the heaven and earth. The earth was tohu wa-bohu (unformed and void), darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God moved on the face of the water.[5] (Genesis 1:1, Genesis 1:2.) God spoke and created, in six days:

- Day one: God spoke light into existence and separated light from darkness.[6] The first open portion ends here.[7] (Genesis 1:3, Genesis 1:4, Genesis 1:5.)

- Second day: God created a firmament in the midst of the waters and separated the waters from the firmament.[8] The second open portion ends here.[9]

- Third day: God gathered the water below the sky, creating land and sea, and God caused vegetation to sprout from the land.[10] The third open portion ends here.[11]

- Fourth day: God set lights in the sky to separate days and years, creating the sun, the moon, and the stars.[12] The fourth open portion ends here.[13]

- Fifth day: God had the waters bring forth living creatures in sea along with the birds of the air and blessed them to be fruitful and multiply.[14] The fifth open portion ends here.[15]

- Sixth day: God had the earth bring forth living creatures from the land, and made humankind in God's image, male and female, giving them dominion over the animals and the earth, and blessed them to be fruitful and multiply.[16] God gave vegetation to them and the animals for food and declared all creation "very good."[17] The sixth open portion ends here with the end of chapter 1.[18]

- Seventh day: God ceased work and blessed the seventh day, declaring it holy.[19] The first reading and the seventh open portion end here.[20]

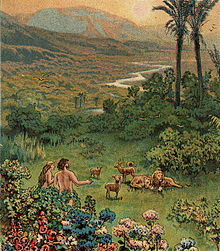

Second reading—Genesis 2:4–19

In the second reading, before any shrub or grass had yet sprouted on earth, and before God had sent rain for the earth, a flow would well up from the ground to water the earth.[21] God formed man from the dust, blew the breath of life into his nostrils, and made him a living being.[22] God planted a garden in the east in Eden, caused to grow there every good and pleasing tree, and placed the tree of life and the Tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the middle of the garden.[23] A river issued from Eden to water the garden, and then divided into four branches: the Pishon, which winds through Havilah, where the gold is; the Gihon, which winds through Cush; the Tigris, which flows east of Asshur; and the Euphrates.[24] God placed the man in the garden of Eden to till and tend it, and freed him to eat from every tree of the garden, except for the tree of knowledge of good and evil, warning that if the man ate of it, he would surely die.[25] Announcing that it was not good for man to be alone and that God would make for him a fitting helper, God formed out of the earth all the beasts and birds and brought them to the man to name.[26] The second reading ends here.[27]

Third reading—Genesis 2:20–3:21

In the third reading, the man Adam named all the animals, but found no fitting helper.[28] So God cast a deep sleep upon the man and took one of his sides and fashioned it into a woman and brought her to the man.[29] The man declared her bone of his bones and flesh of his flesh, and called her woman.[30] Thus a man leaves his parents and clings to his wife, so that they become one flesh.[31] The man and the woman were naked, but felt no shame.[32] The serpent (נָּחָשׁ, nachash), the shrewdest of the beasts, asked the woman whether God had really forbidden her to eat any of the fruit in the garden.[33] The woman replied that they could eat any fruit other than that of the tree in the middle of the garden, which God had warned them neither to eat nor to touch, on pain of death.[34] The serpent told the woman that she would not die, but that as soon as she ate the fruit, her eyes would be opened and she would be like divine beings who knew good and evil.[35] When the woman saw that the tree was good for food, pleasing in appearance, and desirable as a source of wisdom, she ate some of its fruit and gave some to her husband to eat.[36] Then their eyes were opened and they saw that they were naked; and they sewed themselves loincloths out of fig leaves.[37] Hearing God move in the garden, they hid in the trees.[38] God asked the man where he was.[39] The man replied that he grew afraid when he heard God, and he hid because he was naked.[40] God asked him who told him that he was naked and whether he had eaten the forbidden fruit.[41] The man replied that the woman whom God put at his side gave him the fruit, and he ate.[42] When God asked the woman what she had done, she replied that the serpent duped her, and she ate.[43] God cursed the serpent to crawl on its belly, to eat dirt, and to live in enmity with the woman and her offspring.[44] A closed portion ends here.[45]

In the continuation of the reading, God cursed the woman to bear children in pain, to desire her husband, and to be ruled by him.[46] A closed portion ends here.[47]

In the continuation of the reading, God cursed Adam to toil to earn his food from the ground, which would sprout thorns and thistles, until he returned to the ground from which he was taken.[48] Adam named his wife Eve, because she was the mother to all.[49] And God made skin garments to clothe Adam and Eve.[50] The third reading and the eighth open portion end here.[51]

Fourth reading—Genesis 3:22–4:18

In the fourth reading, remarking that the man had become like God, knowing good and bad, God became concerned that man should also eat from the tree of life and live forever, so God banished him from the garden of Eden, to till the soil.[52] God drove the man out, and stationed cherubim and a fiery ever-turning sword east of the garden to guard the tree of life.[53] A closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 3.[54]

In the continuation of the reading in chapter 4, Eve bore Cain and Abel, who became a farmer and a shepherd respectively.[55] Cain brought God an offering from the fruit of the soil, and Abel brought the choicest of the firstlings of his flock.[56] God paid heed to Abel and his offering, but not to Cain and his, distressing Cain.[57] God asked Cain why he was distressed, because he had free will, and if he acted righteously, he would be happy, but if he did not, sin crouched at the door.[58] Cain spoke to Abel, and when they were in the field, Cain killed Abel.[59] When God asked Cain where his brother was, Cain replied that he did not know, asking if he was his brother's keeper.[60] God asked Cain what he had done, as his brother's blood cried out to God from the ground.[61] God cursed Cain to fail at farming and to become a ceaseless wanderer.[62] Cain complained to God that his punishment was too great to bear, as anyone who met him might kill him.[63] So God put a mark on Cain and promised to take sevenfold vengeance on anyone who would kill him.[64] Cain left God's presence and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden.[65] Cain had a son, Enoch, and founded a city, and named it after Enoch.[66] Enoch had a son Irad; and Irad had a son Mehujael; and Mehujael had a son Methushael; and Methushael had a son Lamech.[67] The fourth reading ends here.[68]

Fifth reading—Genesis 4:19–22

In the short fifth reading, Lamech took two wives: Adah and Zillah.[69] Adah bore Jabal, the ancestor of those who dwell in tents and amidst herds, and Jubal, the ancestor of all who play the lyre and the pipe.[70] And Zillah bore Tubal-cain, who forged implements of copper and iron. The sister of Tubal-cain was Naamah.[71] The fifth reading ends here.[68]

Sixth reading—Genesis 4:23–5:24

In the sixth reading, Lamech told his wives that he had slain a young man for bruising him, and that if Cain was avenged sevenfold, then Lamech should be avenged seventy-sevenfold.[72] Adam and Eve had a third son and named him Seth, meaning "God has provided me with another offspring in place of Abel."[73] Seth had a son named Enosh, and then men began to invoke the Lord by name.[74] A closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 4.[75]

In the continuation of the reading in chapter 5, after the birth of Seth, Adam had more sons and daughters, and lived a total of 930 years before he died.[76] A closed portion ends here.[77]

In the continuation of the reading, Adam's descendants and their lifespans were: Seth, 912 years; Enosh, 905 years; Kenan, 910 years; Mahalalel, 895 years; and Jared, 962 years.[78] A closed portion ends after the account of each descendant.[79]

In the continuation of the reading, Jared's son Enoch had a son Methuselah and subsequently walked with God for 300 years, and when Enoch reached age 365, God took him.[80] The sixth reading and a closed portion end here.[81]

Seventh reading—Genesis 5:25–6:8

In the seventh reading, Methuselah had a son Lamech and lived 969 years.[82] A closed portion ends here.[81]

In the continuation of the reading, Lamech had a son Noah, saying that Noah would provide relief from their work and toil on the soil that God had cursed.[83] Lamech lived 777 years.[84] A closed portion ends here.[81]

In the continuation of the reading, when Noah had lived 500 years, he had three sons: Shem, Ham, and Japheth.[85] God set the days allowed to man at 120 years.[86] Divine beings admired and took wives from among the daughters of men, who bore the Nephilim, heroes of old, men of renown.[87] The ninth open portion ends here.[88]

As the reading continues with the maftir (מפטיר) reading that concludes the parashah,[88] God saw how great man's wickedness was and how man's every plan was evil, and God regretted making man.[89] God expressed an intention to blot men and animals from the earth, but Noah found God's favor.[90] The seventh reading, the tenth open portion, and the parashah end here.[91]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[92]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022, 2025, 2028 ... | 2023, 2026, 2029 ... | 2024, 2027, 2030 ... | |

| Reading | 1:1–2:3 | 2:4–4:26 | 5:1–6:8 |

| 1 | 1:1–5 | 2:4–9 | 5:1–5 |

| 2 | 1:6–8 | 2:10–19 | 5:6–8 |

| 3 | 1:9–13 | 2:20–25 | 5:9–14 |

| 4 | 1:14–19 | 3:1–21 | 5:15–20 |

| 5 | 1:20–23 | 3:22–24 | 5:21–24 |

| 6 | 1:24–31 | 4:1–18 | 5:25–31 |

| 7 | 2:1–3 | 4:19–26 | 5:32–6:8 |

| Maftir | 2:1–3 | 4:23–26 | 6:5–8 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Genesis chapter 1

Noting that Sargon of Akkad was the first to use a seven-day week, Professor Gregory S. Aldrete speculated that the Israelites may have adopted the idea from the Akkadian Empire.[93]

Genesis chapter 4

The NIV Archaeological Study Bible notes that the word translated "crouches" (רֹבֵץ, roveitz) in Genesis 4:7 is the same as an ancient Babylonian word used to describe a demon lurking behind a door, threatening the people inside.[94]

In inner-biblical interpretation

Genesis chapter 2

The Sabbath

Genesis 2:1–3 refers to the Sabbath. Commentators note that the Hebrew Bible repeats the commandment to observe the Sabbath 12 times.[95]

Genesis 2:1–3 reports that on the seventh day of Creation, God finished God’s work, rested, and blessed and hallowed the seventh day.

The Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20:8–11 commands that one remember the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work, for in six days God made heaven and earth and rested on the seventh day, blessed the Sabbath, and hallowed it. Deuteronomy 5:12–15 commands that one observe the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work—so that one's subordinates might also rest—and remember that the Israelites were servants in the land of Egypt, and God brought them out with a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm.

In the incident of the manna in Exodus 16:22–30, Moses told the Israelites that the Sabbath is a solemn rest day; prior to the Sabbath one should cook what one would cook and lay up food for the Sabbath. And God told Moses to let no one go out of one's place on the seventh day.

In Exodus 31:12–17, just before giving Moses the second Tablets of Stone, God commanded that the Israelites keep and observe the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a sign between God and the children of Israel forever, for in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God rested.

In Exodus 35:1–3, just before issuing the instructions for the Tabernacle, Moses again told the Israelites that no one should work on the Sabbath, specifying that one must not kindle fire on the Sabbath.

In Leviticus 23:1–3, God told Moses to repeat the Sabbath commandment to the people, calling the Sabbath a holy convocation.

The prophet Isaiah taught in Isaiah 1:12–13 that iniquity is inconsistent with the Sabbath. In Isaiah 58:13–14, the prophet taught that if people turn away from pursuing or speaking of business on the Sabbath and call the Sabbath a delight, then God will make them ride upon the high places of the earth and will feed them with the heritage of Jacob. And in Isaiah 66:23, the prophet taught that in times to come, from one Sabbath to another, all people will come to worship God.

The prophet Jeremiah taught in Jeremiah 17:19–27 that the fate of Jerusalem depended on whether the people abstained from work on the Sabbath, refraining from carrying burdens outside their houses and through the city gates.

The prophet Ezekiel told in Ezekiel 20:10–22 how God gave the Israelites God's Sabbaths, to be a sign between God and them, but the Israelites rebelled against God by profaning the Sabbaths, provoking God to pour out God's fury upon them, but God stayed God's hand.

In Nehemiah 13:15–22, Nehemiah told how he saw some treading winepresses on the Sabbath, and others bringing all manner of burdens into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day, so when it began to be dark before the Sabbath, he commanded that the city gates be shut and not opened till after the Sabbath and directed the Levites to keep the gates to sanctify the Sabbath.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:

Genesis chapter 2

The Book of Jubilees interpreted God's warning to Adam in Genesis 2:17 that "on the day that you eat of it you shall die" in the light of the words of Psalm 90:4 that "a thousand years in [God's] sight are but as yesterday," noting that Adam died 70 years short of the 1000 years that would constitute one day in the testimony of the heavens.[96] And the Books of 4 Ezra (or 2 Esdras) and 2 Baruch interpreted Genesis 2:17 to teach that because Adam transgressed God's commandment, God decreed death to Adam and his descendants for all time.[97]

Genesis chapter 4

Philo saw Cain as an example of a "self-loving man" who (in Genesis 4:3) showed his gratitude to God too slowly and then not from the first of his fruits. Philo taught that we should hurry to please God without delay. Thus Deuteronomy 23:22 enjoins, "If you vow a vow, you shall not delay to perform it." Philo explained that a vow is a request to God for good things, and Deuteronomy 23:22 thus enjoins that when one has received them, one must offer gratitude to God as soon as possible. Philo divided those who fail to do so into three types: (1) those who forget the benefits that they have received, (2) those who from an excessive conceit look upon themselves and not God as the authors of what they receive, and (3) those who realize that God caused what they received, but still say that they deserved it, because they are worthy to receive God's favor. Philo taught that Scripture opposes all three. Philo taught that Deuteronomy 8:12–14 replies to the first group who forget, "Take care, lest when you have eaten and are filled, and when you have built fine houses and inhabited them, and when your flocks and your herds have increased, and when your silver and gold, and all that you possess is multiplied, you be lifted up in your heart, and forget the Lord your God." Philo taught that one does not forget God when one remembers one's own nothingness and God's exceeding greatness. Philo interpreted Deuteronomy 8:17 to reprove those who look upon themselves as the cause of what they have received, telling them: "Say not my own might, or the strength of my right hand has acquired me all this power, but remember always the Lord your God, who gives you the might to acquire power." And Philo read Deuteronomy 9:4–5 to address those who think that they deserve what they have received when it says, "You do not enter into this land to possess it because of your righteousness, or because of the holiness of your heart; but, in the first place, because of the iniquity of these nations, since God has brought on them the destruction of wickedness; and in the second place, that He may establish the covenant that He swore to our Fathers." Philo interpreted the term "covenant" figuratively to mean God's graces. Thus Philo concluded that if we discard forgetfulness, ingratitude, and self-love, we shall not longer through our delay miss attaining the genuine worship of God, but we shall meet God, having prepared ourselves to do the things that God commands us.[98]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:

Genesis chapter 1

Rabbi Jonah taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that the world was created with a letter bet (the first letter in Genesis 1:1, which begins בְּרֵאשִׁית, בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים, bereishit bara Elohim, "In the beginning God created"), because just as the letter bet is closed at the sides but open in front, so one is not permitted to investigate what is above and what is below, what is before and what is behind. Similarly, Bar Kappara reinterpreted the words of Deuteronomy 4:32 to say, "ask not of the days past, which were before you, since the day that God created man upon the earth," teaching that one may speculate from the day that days were created, but one should not speculate on what was before that. And one may investigate from one end of heaven to the other, but one should not investigate what was before this world.[99] Both Rabbi Joḥanan and Rabbi Eleazar (or other say Resh Lakish) compared this to a human king who instructed his servants to build a great palace on a dunghill. They built it for him. Thereafter, the king did not wish to hear mention of the dunghill.[100] Similarly, the Mishnah taught that one should not teach about the Creation to more than one student.[101]

A Midrash (rabbinic commentary) explained that six things preceded the creation of the world: the Torah and the Throne of Glory were created, the creation of the Patriarchs was contemplated, the creation of Israel was contemplated, the creation of the Temple in Jerusalem was contemplated, and the name of the Messiah was contemplated, as well as repentance.[102]

Rav Zutra bar Tobiah said in the name of Rav that the world was created with ten things: (1) wisdom, (2) understanding, (3) reason, (4) strength, (5) rebuke, (6) might, (7) righteousness, (8) judgment, (9) loving-kindness, and (10) compassion. The Gemara cited verses to support Rav Zutra's proposition: wisdom and understanding, as Proverbs 3:19 says, "The Lord by wisdom founded the earth; and by understanding established the heavens"; reason, as Proverbs 3:20 says, "By His reason the depths were broken up"; strength and might, as Psalm 65:7 says, "Who by Your strength sets fast the mountains, Who is girded about with might"; rebuke, as Job 26:11 says, "The pillars of heaven were trembling, but they became astonished at His rebuke"; righteousness and judgment, as Psalm 89:15 says, "Righteousness and judgment are the foundation of Your throne"; and loving-kindness and compassion, as Psalm 25:6 says, "Remember, O Lord, Your compassions and Your mercies; for they have been from of old."[103]

A Midrash taught that a heretic once asked Rabbi Akiva who created the world. Rabbi Akiva answered that God had. The heretic demanded that Rabbi Akiva give him clear proof. Rabbi Akiva asked him what he was wearing. The heretic said that it was a garment. Rabbi Akiva asked him who made it. The heretic replied that a weaver had. Rabbi Akiva demanded that the heretic give him proof. The heretic asked Rabbi Akiva whether he did not realize that a garment is made by a weaver. Rabbi Akiva replied by asking the heretic whether he did not realize that the world was made by God. When the heretic had left, Rabbi Akiva's disciples asked him to explain his proof. Rabbi Akiva replied that just as a house implies a builder, a dress implies a weaver, and a door implies a carpenter, so the world proclaims the God who created it.[104]

It was taught in a Baraita that King Ptolemy brought together 72 elders, placed them in 72 separate rooms without telling them why, and directed each of them to translate the Torah. God then prompted each one of them, and they all conceived the same idea and wrote for Genesis 1:1: "God created in the beginning" (instead of "In the beginning, God created," to prevent readers from reading into the text two creating powers, "In the beginning" and "God").[105]

Rav Haviva of Hozna'ah told Rav Assi (or some say that Rav Assi said) that the words, "And it came to pass in the first month of the second year, on the first day of the month," in Exodus 40:17 showed that the Tabernacle was erected on the first of Nisan. With reference to this, a Tanna taught that the first of Nisan took ten crowns of distinction by virtue of the ten momentous events that occurred on that day. The first of Nisan was: (1) the first day of the Creation (as reported in Genesis 1:1–5), (2) the first day of the princes' offerings (as reported in Numbers 7:10–17), (3) the first day for the priesthood to make the sacrificial offerings (as reported in Leviticus 9:1–21), (4) the first day for public sacrifice, (5) the first day for the descent of fire from Heaven (as reported in Leviticus 9:24), (6) the first for the priests' eating of sacred food in the sacred area, (7) the first for the dwelling of the Shechinah in Israel (as implied by Exodus 25:8), (8) the first for the Priestly Blessing of Israel (as reported in Leviticus 9:22, employing the blessing prescribed by Numbers 6:22–27), (9) the first for the prohibition of the high places (as stated in Leviticus 17:3–4), and (10) the first of the months of the year (as instructed in Exodus 12:2).[106]

Similarly, a Baraita compared the day that God created the universe with the day that the Israelites dedicated the Tabernacle. Reading the words of Leviticus 9:1, "And it came to pass on the eighth day," a Baraita taught that on that day (when the Israelites dedicated the Tabernacle) there was joy before God as on the day when God created heaven and earth. For Leviticus 9:1 says, "And it came to pass (וַיְהִי, va-yehi) on the eighth day," and Genesis 1:5 says, "And there was (וַיְהִי, va-yehi) one day."[107]

The Mishnah taught that God created the world with ten Divine utterances. Noting that surely God could have created the world with one utterance, the Mishnah asks what we are meant to learn from this, replying, if God had created the world by a single utterance, men would think less of the world, and have less compunction about undoing God's creation.[108]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that the ten utterances with which God created the world account for the rule taught in a Baraita cited by Rabbi Shimi that no fewer than ten verses of the Torah should be read in the synagogue. The ten verses represent God's ten utterances. The Gemara explained that the ten utterances are indicated by the ten uses of "And [God] said" in Genesis 1. To the objection that these words appear only nine times in Genesis 1, the Gemara responded that the words "In the beginning" also count as a creative utterance. For Psalm 33:6 says, "By the word of the Lord the heavens were made, and all the host of them by the breath of his mouth" (and thus one may learn that the heavens and earth were created by Divine utterance before the action of Genesis 1:1 takes place).[109]

Rav Judah said in Rav's name that ten things were created on the first day: (1) heaven, (2) earth, (3) chaos (תֹהוּ, tohu), (4) desolation or void (בֹהוּ, bohu), (5) light, (6) darkness, (7) wind, (8) water, (9) the length of a day, and (10) the length of a night. The Gemara cited verses to support Rav Judah's proposition: heaven and earth, as Genesis 1:1 says, "In the beginning God created heaven and earth"; tohu and bohu, as Genesis 1:2 says, "and the earth was tohu and bohu"; darkness, as Genesis 1:2 says, "and darkness was upon the face of the deep; light, as Genesis 1:3 says, "And God said, ‘Let there be light'"; wind and water, as Genesis 1:2 says, "and the wind of God hovered over the face of the waters"; and the length of a day and the length of a night, as Genesis 1:5 says, "And there was evening and there was morning, one day." A Baraita taught that tohu (chaos) is a green line that encompasses the world, out of which darkness proceeds, as Psalm 18:12 says, "He made darkness His hiding-place round about Him"; and bohu (desolation) means the slimy stones in the deep out of which the waters proceed, as Isaiah 34:11 says, "He shall stretch over it the line of confusion (tohu) and the plummet of emptiness (bohu)." The Gemara questioned Rav Judah's assertion that light was created on the first day, as Genesis 1:16–17 reports that "God made the two great lights ... and God set them in the firmament of the heaven," and Genesis 1:19 reports that God did so on the fourth day. The Gemara explained that the light of which Rav Judah taught was the light of which Rabbi Eleazar spoke when he said that by the light that God created on the first day, one could see from one end of the world to the other; but as soon as God saw the corrupt generations of the Flood and the Dispersion, God hid the light from them, as Job 38:15 says, "But from the wicked their light is withheld." Rather, God reserved the light of the first day for the righteous in the time to come, as Genesis 1:4 says, "And God saw the light, that it was good." The Gemara noted a dispute among the Tannaim over this interpretation. Rabbi Jacob agreed with the view that by the light that God created on the first day one could see from one end of the world to the other. But the Sages equated the light created on the first day with the lights of which Genesis 1:14 speaks, which God created on the first day, but placed in the heavens on the fourth day.[110]

Rav Judah taught that when God created the world, it went on expanding like two unraveling balls of thread, until God rebuked it and brought it to a standstill, as Job 26:21 says, "The pillars of heaven were trembling, but they became astonished at His rebuke." Similarly, Resh Lakish taught that the words "I am God Almighty" (אֵל שַׁדַּי, El Shaddai) in Genesis 35:11 mean, "I am He Who said to the world: ‘Enough!'" (דַּי, Dai). Resh Lakish taught that when God created the sea, it went on expanding, until God rebuked it and caused it to dry up, as Nahum 1:4 says, "He rebukes the sea and makes it dry, and dries up all the rivers."[111]

The Rabbis reported in a Baraita that the House of Shammai taught that heaven was created first and the earth was created afterwards, as Genesis 1:1 says, "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth." But the House of Hillel taught that the earth was created first and heaven was created afterwards, as Genesis 2:4 says, "In the day that the Lord God made earth and heaven." The House of Hillel faulted the House of Shammai for believing that one can build a house's upper stories and afterwards builds the house, as Amos 9:6 calls heaven God's "upper chambers," saying, "It is He Who builds His upper chambers in the heaven and has founded His vault upon the earth." The House of Shammai, in turn, faulted the House of Hillel for believing that a person builds a footstool first, and afterwards builds the throne, as Isaiah 66:1 calls heaven God's throne and the earth God's footstool. But the Sages said that God created both heaven and earth at the same time, as Isaiah 48:13 says, "My hand has laid the foundation of the earth, and My right hand has spread out the heavens: When I call to them, they stand up together." The House of Shammai and the House of Hillel, however, interpreted the word "together" in Isaiah 48:13 to mean only that heaven and earth cannot be separated from each another. Resh Lakish reconciled the differing verses by positing that God created heaven first, and afterwards created the earth; but when God put them in place, God put the earth in place first, and afterwards put heaven in place.[112]

The Gemara told that Alexander the Great asked the Elders of the Negev which was created first—the heavens or the earth. They answered that the heavens were created first, as Genesis 1:1 says, "In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth." Alexander then asked which was created first—light or darkness. They answered that this matter has no solution, as the verses do not indicate an answer. The Gemara asked why the Elders did not say that the darkness was created first, as Genesis 1:2 says, "Now the earth was unformed and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep," and only after does Genesis 1:3 say, "And God said: 'Let there be light. And there was light.'" The Gemara answered its own question by reporting that the Elders reasoned that they must not answer this question, lest Alexander then ask questions about Creation that may not be discussed—what is above the firmament and what is below the earth, what was before Creation, and what will be after the end of the world. The Gemara then asked: if the Elders were concerned about such proscribed questions, then with regard to the creation of heaven as well, they should not have said anything to Alexander, so why did they answer the question about heaven, but not the one about darkness? The Gemara again answered its own question by reporting that initially they assumed that it was merely happenstance that Alexander asked about the creation of the universe, and therefore there was no need for caution. But once they saw that Alexander again asked about the same general matter, they reasoned that they should not answer further, lest Alexander then ask what is above the firmament and what is below the earth, what was before Creation, and what will be after the end of the world.[113]

Rabbi Jose bar Ḥanina taught that "heaven" (שָּׁמַיִם, shamayim) means "there is water" (sham mayim). A Baraita taught that it means "fire and water" (eish u'mayim), teaching that God brought fire and water together and mixed them to make the firmament.[114]

Rabbi Yannai taught that from the very beginning of the world’s creation, God foresaw the deeds of the righteous and the wicked. Rabbi Yannai taught that Genesis 1:2, "And the earth was desolate," alludes to the deeds of the wicked; Genesis 1:3, "And God said: 'Let there be light,'" to those of the righteous; Genesis 1:4, "And God saw the light, that it was good," to the deeds of the righteous; Genesis 1:4, "And God made a division between the light and the darkness": between the deeds of the righteous and those of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, "And God called the light day," alludes to the deeds of the righteous; Genesis 1:5, "And the darkness called God night," to those of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, "and there was evening," to the deeds of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, "and there was morning," to those of the righteous. And Genesis 1:5, "one day" teaches that God gave the righteous one day—Yom Kippur.[115] Similarly, Rabbi Judah bar Simon interpreted Genesis 1:5, "And God called the light day," to symbolize Jacob/Israel; "and the darkness God called night," to symbolize Esau; "and there was evening," to symbolize Esau; "and there was morning," to symbolize Jacob. And "one day" teaches that God gave Israel one unique day over which darkness has no influence—the Day of Atonement.[116]

Interpreting the words "God called the light (אוֹר, or) day" in Genesis 1:5, the Gemara hypothesized that or (אוֹר) might thus be read to mean "daytime." The Gemara further hypothesized from its use in Genesis 1:5 that or (אוֹר) might be read to mean the time when light begins to appear—that is, daybreak. If so, then one would need to interpret the continuation of Genesis 1:5, "and the darkness God called night," to teach that "night" (לָיְלָה, lailah) similarly must mean the advancing of darkness. But it is established (in Babylonian Talmud Berakhot[117]) that day continues until stars appear. The Gemara therefore concluded that when "God called the light" in Genesis 1:5, God summoned the light and appointed it for duty by day, and similarly God summoned the darkness and appointed it for duty by night.[118]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that once Rabbi Joshua ben Ḥananiah was standing on a step on the Temple Mount, and Ben Zoma (who was younger than Rabbi Joshua) saw him but did not stand up before him in respect. So Rabbi Joshua asked Ben Zoma what was up. Ben Zoma replied that he was staring at the space between the upper and the lower waters (described in Genesis 1:6–7). Ben Zoma said that there is only a bare three fingers' space between the upper and the lower waters. Ben Zoma reasoned that Genesis 1:2 says, "And the spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters," implying a distance similar to that of a mother dove that hovers over her young without touching them. But Rabbi Joshua told his disciples that Ben Zoma was still outside the realm of understanding. Rabbi Joshua noted that Genesis 1:2 says that "the spirit of God hovered over the face of the water" on the first day of Creation, but God divided the waters on the second day, as Genesis 1:6–7 reports. (And thus the distance that God hovered above the waters need not be the distance between the upper and lower waters). The Gemara presented various views of how great the distance is between the upper and the lower waters. Rav Aha bar Jacob said that the distance was a hair's breadth. The Rabbis said that the distance was like that between the planks of a bridge. Mar Zutra (or some say Rav Assi) said that the distance was like that between two cloaks spread one over another. And others said that the distance was like that between two cups nested one inside the other.[119]

Rabbi Judah ben Pazi noted that a similar word appears in both Genesis 1:6—where רָקִיעַ, rakiya is translated as "firmament"—and Exodus 39:3—where וַיְרַקְּעוּ, vayraku is translated as "and they flattened." He thus deduced from the usage in Exodus 39:3 that Genesis 1:6 taught that on the second day of creation, God spread the heavens flat like a cloth.[120] Or Rabbi Judah the son of Rabbi Simon deduced from Exodus 39:3 that Genesis 1:6 meant "let a lining be made for the firmament."[121]

A Baraita taught that the upper waters created in Genesis 1:6–7 remain suspended by Divine command, and their fruit is the rainwater, and thus Psalm 104:13 says: "The earth is full of the fruit of Your works." This view accords with that of Rabbi Joshua. Rabbi Eliezer, however, interpreted Psalm 104:13 to refer to other handiwork of God.[122]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that on the day that God said in Genesis 1:9, "Let the waters be gathered together," God laid the foundation for the miracle of the splitting of the sea in the Exodus from Egypt. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer recounted that in the Exodus, Moses cried out to God that the enemy was behind them and the sea in front of them, and asked which way they should go. So God sent the angel Michael, who became a wall of fire between the Israelites and the Egyptians. The Egyptians wanted to follow after the Israelites, but they are unable to come near because of the fire. The angels saw the Israelites' misfortune all the night, but they uttered neither praise nor sanctification, as Exodus 14:20 says, "And the one came not near the other all the night." God told Moses (as Exodus 14:16 reports) to "Stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it." So (as Exodus 14:21 reports) "Moses stretched out his hand over the sea," but the sea refused to be divided. So God looked at the sea, and the waters saw God's Face, and they trembled and quaked, and descended into the depths, as Psalm 77:16 says, "The waters saw You, O God; the waters saw You, they were afraid: the depths also trembled." Rabbi Eliezer taught that on the day that God said in Genesis 1:9, "Let the waters be gathered together," the waters congealed, and God made them into twelve valleys, corresponding to the twelve tribes, and they were made into walls of water between each path, and the Israelites could see each other, and they saw God, walking before them, but they did not see the heels of God's feet, as Psalm 77:19 says, "Your way was in the sea, and Your paths in the great waters, and Your footsteps were not known."[123]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that God created the sun and the moon in Genesis 1:16 on the 28th of Elul. The entire Hebrew calendar—years, months, days, nights, seasons, and intercalation—were before God, and God intercalated the years and delivered the calculations to Adam in the Garden of Eden, as Genesis 5:1 can be read, "This is the calculation for the generations of Adam." Adam handed on the tradition to Enoch, who was initiated in the principle of intercalation, as Genesis 5:22 says, "And Enoch walked with God." Enoch passed the principle of intercalation to Noah, who conveyed the tradition to Shem, who conveyed it to Abraham, who conveyed it to Isaac, who conveyed it to Jacob, who conveyed it to Joseph and his brothers. When Joseph and his brothers died, the Israelites ceased to intercalate, as Exodus 1:6 reports, "And Joseph died, and all his brethren, and all that generation." God then revealed the principles of the Hebrew calendar to Moses and Aaron in Egypt, as Exodus 12:1–2 reports, "And the Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt saying, 'This month shall be to you the beginning of months.'" The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer deduced from the word "saying" in Exodus 12:1 that God said to Moses and Aaron that until then, the principle of intercalation had been with God, but from then on it was their right to intercalate the year. Thus the Israelites intercalated the year and will until Elijah returns to herald in the Messianic Age.[124]

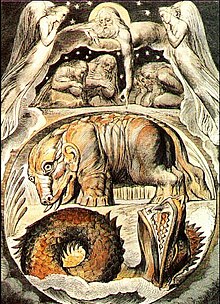

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that the words "and God created the great sea-monsters" in Genesis 1:21 referred to Leviathan the slant serpent and Leviathan the tortuous serpent, also referred to in Isaiah 27:1 Rav Judah taught in the name of Rav that God created all living things in this world male and female, including Leviathan the slant serpent and Leviathan the tortuous serpent. Had they mated with one another, they would have destroyed the world, so God castrated the male and killed the female, preserving it in salt for the righteous in the world to come, as reported in Isaiah 27:1 when it says: "And he will slay the dragon that is in the sea." Similarly, God also created male and female the "Behemoth upon a thousand hills" referred to in Psalm 50:10 Had they mated, they also would have destroyed the world, so God castrated the male and cooled the female and preserved it for the righteous for the world to come. Rav Judah taught further in the name of Rav that when God wanted to create the world, God told the angel of the sea to open the angel's mouth and swallow all the waters of the world. When the angel protested, God struck the angel dead, as reported in Job 26:12, when it says: "He stirs up the sea with his power and by his understanding he smites through Rahab." Rabbi Isaac deduced from this that the name of the angel of the sea was Rahab, and had the waters not covered Rahab, no creature could have stood the smell.[125]

Rabbi Joḥanan explained that Genesis 1:26 uses the plural pronoun when God says, "Let us make man," to teach that God does nothing without consulting God's Heavenly Court of angels (thus instructing us in the proper conduct of humility among subordinates).[126]

Noting that Genesis 1:26 uses the plural pronoun when God says, "Let us make man," the heretics asked Rabbi Simlai how many deities created the world. Rabbi Simlai replied that wherever one finds a point apparently supporting the heretics, one finds the refutation nearby in the text. Thus Genesis 1:26 says, "Let us make man" (using the plural pronoun), but then Genesis 1:27 says, "And God created" (using the singular pronoun). When the heretics had departed, Rabbi Simlai's disciples told him that they thought that he had dismissed the heretics with a mere makeshift and asked him for the real answer. Rabbi Simlai then told his disciples that in the first instance, God created Adam from dust and Eve from Adam, but thereafter God would create humans (in the words of Genesis 1:26) "in Our image, after Our likeness," neither man without woman nor woman without man, and neither of them without the Shechinah (the indwelling nurturing presence of God, designated with a feminine noun).[127]

It was taught in a Baraita that when King Ptolemy brought together 72 elders, placed them in 72 separate rooms without telling them why, and directed each of them to translate the Torah, God prompted each one of them and they all conceived the same idea and wrote for Genesis 1:26, "I shall make man in image and likeness" (instead of "Let us make," to prevent readers from reading into the text multiple creating powers).[105]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that God spoke to the Torah the words of Genesis 1:26, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness." The Torah answered that the man whom God sought to create would be limited in days and full of anger and would come into the power of sin. Unless God would be long-suffering with him, the Torah continued, it would be well for man not to come into the world. God asked the Torah whether it was for nothing that God is called "slow to anger" and "abounding in love."[128] God then set about making man.[129]

Rabbi Eleazar read the words "since the day that God created man upon the earth, and ask from the one side of heaven" in Deuteronomy 4:32 to read, "from the day that God created Adam on earth and to the end of heaven." Thus, Rabbi Eleazar read Deuteronomy 4:32 to intimate that when God created Adam in Genesis 1:26–27, Adam extended from the earth to the sky. But as soon as Adam sinned, God placed God's hand upon Adam and diminished him, as Psalm 139:5 says: "You have fashioned me after and before and laid Your hand upon me." Similarly, Rav Judah in the name of Rav taught that when God created Adam in Genesis 1:26–27, Adam extended from one end of the world to the other, reading Deuteronomy 4:32 to read, "Since the day that God created man upon the earth, and from one end of heaven to the other." (And Rav Judah in the name of Rav also taught that as soon as Adam sinned, God placed God's hand upon Adam and diminished him.) The Gemara reconciled the interpretations of Rabbi Eleazar and Rav Judah in the name of Rav by concluding that the distance from the earth to the sky must equal the distance from one end of heaven to the other.[130]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that for two and a half years the House of Shammai and the House of Hillel debated, the House of Shammai asserting that it would have been better for humanity not to have been created, and the House of Hillel maintaining that it is better that humanity was created. They finally took a vote and decided that it would have been better for humanity not to have been created, but now that humanity has been created, let us investigate our past deeds or, as others say, let us examine our future actions.[131]

The Mishnah taught that in Second Temple times, Jews would acknowledge God's creation and read the verses of the creation story when representatives of the people would assemble (in watches or ma'amadot) to participate in sacrifices made in Jerusalem on their behalf.[132] The people of the delegation would fast four days during the week that they assembled. On the first day (Sunday), they would read Genesis 1:1–8 On the second day, they would read Genesis 1:6–13 On the third day, they would read Genesis 1:9–19 On the fourth day, they would read Genesis 1:14–23 On the fifth day, they would read Genesis 1:20–31 And on the sixth day, they would read Genesis 1:24–2:3[133] Rabbi Ammi taught that if had not been for the worship of these delegations, heaven and earth would not be firmly established, reading Jeremiah 33:25 to say, "If it were not for My covenant [observed] day and night, I would not have established the statutes of heaven and earth." And Rabbi Ammi cited Genesis 15:8–9 to show that when Abraham asked God how Abraham would know that his descendants would inherit the Land notwithstanding their sins, God replied by calling on Abraham to sacrifice several animals. Rabbi Ammi then reported that Abraham asked God what would happen in times to come when there would be no Temple at which to offer sacrifices. Rabbi Ammi reported that God replied to Abraham that whenever Abraham's descendants will read the sections of the Torah dealing with the sacrifices, God will account it as if they had brought the offerings, and forgive all their sins.[134]

It was recorded in Rabbi Joshua ben Levi's notebook that a person born on the first day of the week (Sunday) will lack one thing. The Gemara explained that the person will be either completely virtuous or completely wicked, because on that day (in Genesis 1:3–5) God created the extremes of light and darkness. A person born on the second day of the week (Monday) will be bad-tempered, because on that day (in Genesis 1:6–7) God divided the waters (and similarly division will exist between this person and others). A person born on the third day of the week (Tuesday) will be wealthy and promiscuous, because on that day (in Genesis 1:11) God created fast-growing herbs. A person born on the fourth day of the week (Wednesday) will be bright, because on that day (in Genesis 1:16–17) God set the luminaries in the sky. A person born on the fifth day of the week (Thursday) will practice kindness, because on that day (in Genesis 1:21) God created the fish and birds (who find their sustenance through God's kindness). A person born on the eve of the Sabbath (Friday evening) will be a seeker. Rav Naḥman bar Isaac explained: a seeker after good deeds. A person born on the Sabbath (Saturday) will die on the Sabbath, because they had to desecrate the great day of the Sabbath on that person's account to attend to the birth. And Rava son of Rav Shila observed that this person shall be called a great and holy person.[135]

Genesis chapter 2

Rava (or some say Rabbi Joshua ben Levi) taught that even a person who prays on the eve of the Sabbath must recite Genesis 2:1–3, "And the heaven and the earth were finished ..." (וַיְכֻלּוּ הַשָּׁמַיִם וְהָאָרֶץ, va-yachulu hashamayim v'haaretz ...), for Rav Hamnuna taught that whoever prays on the eve of the Sabbath and recites "and the heaven and the earth were finished," the Writ treats as though a partner with God in the Creation, for one may read va-yachulu (וַיְכֻלּוּ)—"and they were finished"—as va-yekallu—"and they finished." Rabbi Eleazar taught that we know that speech is like action because Psalm 33:6 says, "By the word of the Lord were the heavens made." Rav Ḥisda said in Mar Ukba's name that when one prays on the eve of the Sabbath and recites "and the heaven and the earth were finished," two ministering angels place their hands on the head of the person praying and say (in the words of Isaiah 6:7), "Your iniquity is taken away, and your sin purged."[136]

It was taught in a Baraita that when King Ptolemy brought together 72 elders, placed them in 72 separate rooms without telling them why, and directed each of them to translate the Torah, God prompted each one of them and they all conceived the same idea and wrote for Genesis 2:2, "And he finished on the sixth day, and rested on the seventh day" (instead of "and He finished on the seventh day," to prevent readers from reading that God worked on the Sabbath).[105]

Similarly, Rabbi asked Rabbi Ishmael the son of Rabbi Jose if he had learned from his father the actual meaning of Genesis 2:2, "And on the seventh day God finished the work that He had been doing" (for surely God finished God's work on the sixth day, not the Sabbath). He compared it to a man striking a hammer on an anvil, raising it by day and bringing it down immediately after nightfall. (In the second between raising the hammer and bringing it down, night began. Thus, he taught that God finished God's work right at the end of the sixth day, so that in that very moment the Sabbath began.) Rabbi Simeon bar Yoḥai taught that mortal humans, who do not know exactly what time it is, must add from the profane to the sacred to avoid working in the sacred time; but God knows time precisely, can enter the Sabbath by a hair's breadth. Genibah and the Rabbis discussed Genesis 2:2–3. Genibah compared it to a king who made a bridal chamber, which he plastered, painted, and adorned, so that all that the bridal chamber lacked was a bride to enter it. Similarly, just then, the world lacked the Sabbath. (Thus, by means of instituting the Sabbath itself, God completed God's work, and humanity's world, on the seventh day.) The Rabbis compared it to a king who made a ring that lacked only a signet. Similarly, the world lacked the Sabbath. And the Midrash taught that this is one of the texts that they changed for King Ptolemy (as they could not expect him to understand these explanations), making Genesis 2:2 read, "And He finished on the sixth day, and rested on the seventh." King Ptolemy (or others say, a philosopher) asked the elders in Rome how many days it took God to create the world. The elders replied that it took God six days. He replied that since then, Gehenna has been burning for the wicked. Reading the words "His work" in Genesis 2:2–3, Rabbi Berekiah said in the name of Rabbi Judah the son of Rabbi Simon that with neither labor nor toil did God create the world, yet Genesis 2:2 says, "He rested ... from all His work." He explained that Genesis 2:2 states it that way to punish the wicked who destroy the world, which was created with labor, and to give a good reward to the righteous who uphold the world, which was created with toil. Reading the words "Because that in it God rested from all God's work of creation that God had done," in Genesis 2:3, the Midrash taught that what was created on the Sabbath, after God rested, was tranquility, ease, peace, and quiet. Rabbi Levi said in the name of Rabbi Jose ben Nehorai that as long as the hands of their Master were working on them, they went on expanding; but when the hands of their Master rested, rest was afforded to them, and thus God gave rest to the world on the seventh day. Rabbi Abba taught that when a mortal king takes his army to their quarters, he does not distribute largesse (rather, he does that only before the troops go into battle), and when he distributes largesse, he does not order a halt. But God ordered a halt and distributed largesse, as Genesis 2:2–3 says, "And He rested ... and He blessed." (Not only did God afford humanity a day of rest, but God also gave humanity the gift of a sacred day.)[137]

Reading Genesis 2:2, "And on the seventh day God finished the work," the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that God created seven dedications (for the creation of each of the seven days). God expressed six of them and reserved one for future generations. Thus, when God created the first day and finished all God's work on it, God dedicated it, as Genesis 1:5 says, "And it was evening, and it was morning, one day." When God created the second day and finished all God's work in it, God dedicated it, as Genesis 1:8 says, "And it was evening, and it was morning, a second day." Similar language appears through the six days of creation. God created the seventh day, but not for work, because Genesis does not say in connection the seventh day, "And it was evening, and it was morning." That is because God reserved the dedication of the seventh day for the generations to come, as Zechariah 14:7 says, speaking of the Sabbath, "And there shall be one day which is known to the Lord; not day, and not night." The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer compared this to a man who had precious utensils that he did not want to leave as an inheritance to anyone but to his son. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that it is likewise with God. God did not want to give the day of blessing and holiness that was before God as an inheritance to anyone but Israel. For when the Israelites left Egypt, before God gave them the Torah, God gave them the Sabbath as an inheritance (as reported in Exodus 16:23). Before God gave Israel the Torah, they kept two Sabbaths, as Nehemiah 9:14 says first, "And You made known to them Your holy Sabbath." And only afterwards did God give them the Torah, as Nehemiah 9:14 says as it continues, "And commanded them commandments, and statutes, and Torah by the hand of Moses, Your servant." God observed and sanctified the Sabbath, and Israel is obliged only to observe and sanctify the Sabbath. For when God gave the Israelites manna, all through the 40 years in the wilderness, God gave it during on the six days during which God had created the world, Sunday through Friday, but on the Sabbath, God did not give them manna. Of course, God had power enough to give them manna every day. But the Sabbath was before God, so God gave the Israelites bread for two days on Friday, as Exodus 16:29 says, "See, for the Lord has given you the Sabbath, therefore he gives you on the sixth day the bread of two days." When the people saw that God observed the Sabbath, they also rested, as Exodus 16:30 says, "So the people rested on the seventh day." Reading Genesis 2:3, "And God blessed the seventh day, and hallowed it," the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that God blessed and hallowed the Sabbath day, and Israel is bound only to keep and to hallow the Sabbath day. Hence the Sages said that those who says the benediction and sanctification over the wine on Friday evenings will have their days increased in this world, and in the world to come. For Proverbs 9:11 says, "For by me your days shall be multiplied," signifying in this world. And Proverbs 9:11 continues, "and the years of your life shall be increased" signifying in the world to come.[138]

Rabbi Simeon noted that nearly everywhere, Scripture gives precedence to the creation of heaven over earth.[139] But Genesis 2:4 says, "the day that the Lord God made earth and heaven" (listing earth before heaven). Rabbi Simeon concluded that Genesis 2:4 thus teaches that the earth is equivalent to heaven.[140]

The Tosefta taught that the generation of the Flood acted arrogantly before God on account of the good that God lavished on them, in part in Genesis 2:6. So (in the words of Job 21:14–15) "they said to God: ‘Depart from us; for we desire not the knowledge of Your ways. What is the Almighty, that we should serve Him? And what profit should we have if we pray unto Him?'" They scoffed that they needed God for only a few drops of rain, and they deluded themselves that they had rivers and wells that were more than enough for them, and as Genesis 2:6 reports, "there rose up a mist from the earth." God noted that they took excess pride based upon the goodness that God lavished on them, so God replied that with that same goodness God would punish them. And thus Genesis 6:17 reports, "And I, behold, I do bring the flood of waters upon the earth."[141]

The Mishnah taught that God created humanity from one person in Genesis 2:7 to teach that Providence considers one who destroys a single person as one who has destroyed an entire world, and Providence considers one who saves a single person as one who has saved an entire world. And God created humanity from one person for the sake of peace, so that none can say that their ancestry is greater than another's. And God created humanity from one person so that heretics cannot say that there are many gods who created several human souls. And God created humanity from one person to demonstrate God's greatness, for people stamp out many coins with one coin press and they all look alike, but God stamped each person with the seal of Adam, and not one of them is like another. Therefore, every person is obliged to say, "For my sake the world was created."[142] It was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Meir used to say that the dust of the first man (from which Genesis 2:7 reports God made Adam) was gathered from all parts of the earth, for Psalm 139:16 says of God, "Your eyes did see my unformed substance," and 2 Chronicles 16:9 says, "The eyes of the Lord run to and fro through the whole earth."[143]

Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that when God began to create the first person, God began to collect dust from the four corners of the world—red, black, white, and yellow. Explaining why God gathered the first person's dust from the four corners of the world, God said that if a person should travel from the east to the west, or from the west to the east, and the time should come for the person to depart from the world, then the earth would not be able to tell the person that the dust of the person's body was not of the earth there, and that the person needed to return to the place from which the person had been created. This teaches that in every place where a person comes or goes, should the person approach the time to die, in that place is the dust of the person's body, and there the person's body will return to the dust, as Genesis 3:19 says, "For dust you are, and to dust shall you return."[144]

Rav Naḥman bar Rav Ḥisda expounded on the words, "Then the Lord God formed (וַיִּיצֶר, wa-yitzer) man," in Genesis 2:7. Rav Naḥman bar Rav Ḥisda taught that the word וַיִּיצֶר, wa-yitzer is written with two yuds (יי) to show that God created people with two inclinations (yetzerim), one good and one evil. Rav Naḥman bar Isaac demurred, arguing that according to this logic, animals, of which Genesis 2:19 writes וַיִּצֶר, wa-yitzer with a single yud, should have no evil inclination (yetzer hara), but we see that they injure, bite, and kick, plainly evincing an evil inclination. Rather, Rabbi Simeon ben Pazzi explained that the two yuds by saying, "Woe is me because of my Creator (yotzri), woe is me because of my evil inclination (yitzri)!" Rabbi Simeon ben Pazzi thus indicated that the two yuds indicate the human condition, where God punishes us for giving in to our evil inclination, but our evil inclination tempts us when we try to resist. Alternatively, Rabbi Jeremiah ben Eleazar explained that the two yuds reflect that God created two countenances in the first man, one man and one woman, back to back, as Psalm 139:5 says, "Behind and before have You formed me."[145]

A Midrash deduced from similarities in the language of the creation of humanity and the Sabbath commandment that God gave Adam the precept of the Sabbath. Reading the report of God’s creating Adam in Genesis 2:15, "And God put him (וַיַּנִּחֵהוּ, vayanihehu) into the Garden of Eden," the Midrash taught that "And God put him (וַיַּנִּחֵהוּ, vayanihehu)" means that God gave Adam the precept of the Sabbath, for the Sabbath commandment uses a similar word in Exodus 20:11, "And rested (וַיָּנַח, vayanach) on the seventh day." Genesis 2:15 continues, "to till it (לְעָבְדָהּ, le'avedah)," and the Sabbath commandment uses a similar word in Exodus 20:9, "Six days shall you labor (תַּעֲבֹד, ta’avod)." And Genesis 2:15 continues, "And to keep it (וּלְשָׁמְרָהּ, ule-shamerah)," and the Sabbath commandment uses a similar word in Deuteronomy 5:12, "Keep (שָׁמוֹר, shamor) the Sabbath day."[146]

Similarly, a Midrash recounts that Rabbi Jeremiah ben Leazar taught that when God created Adam, God created him a hermaphrodite—two bodies, male and female, joined together—for Genesis 5:2 says, "male and female created He them ... and called their name Adam." Rabbi Samuel bar Naḥman taught that when God created Adam, God created Adam double-faced, then God split Adam and made Adam of two backs, one back on this side and one back on the other side. An objection was raised that Genesis 2:21 says, "And He took one of his ribs" (implying that God created Eve separately from Adam). Rabbi Samuel bar Naḥman replied that the word read as "rib"—מִצַּלְעֹתָיו, mi-zalotav—actually means one of Adam's sides, just as one reads in Exodus 26:20, "And for the second side (צֶלַע, zela) of the tabernacle."[147]

Reading God's observation in Genesis 2:18 that "it is not good that the man should be alone," a Midrash taught that a man without a wife dwells without good, without help, without joy, without blessing, and without atonement. Without good, as Genesis 2:18 says that "it is not good that the man should be alone." Without help, as in Genesis 2:18, God says, "I will make him a help meet for him." Without joy, as Deuteronomy 14:26 says, "And you shall rejoice, you and your household" (implying that one can rejoice only when there is a "household" with whom to rejoice). Without a blessing, as Ezekiel 44:30 can be read, "To cause a blessing to rest on you for the sake of your house" (that is, for the sake of your wife). Without atonement, as Leviticus 16:11 says, "And he shall make atonement for himself, and for his house" (implying that one can make complete atonement only with a household). Rabbi Simeon said in the name of Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, without peace too, as 1 Samuel 25:6 says, "And peace be to your house." Rabbi Joshua of Siknin said in the name of Rabbi Levi, without life too, as Ecclesiastes 9:9 says, "Enjoy life with the wife whom you love." Rabbi Hiyya ben Gomdi said, also incomplete, as Genesis 5:2 says, "male and female created He them, and blessed them, and called their name Adam," that is, "man" (and thus only together are they "man"). Some say a man without a wife even impairs the Divine likeness, as Genesis 9:6 says, "For in the image of God made God man," and immediately thereafter Genesis 9:7 says, "And you, be fruitful, and multiply (implying that the former is impaired if one does not fulfill the latter).[148]

The Gemara taught that all agree that there was only one formation of humankind (not a separate creation of man and woman). Rav Judah, however, noted an apparent contradiction: Genesis 1:27 says, "And God created man in His own image" (in the singular), while Genesis 5:2 says, "Male and female created He them" (in the plural). Rav Judah reconciled the apparent contradiction by concluding that in the beginning God intended to create two human beings, and in the end God created only one human being.[149]

Rav and Samuel offered different explanations of the words in Genesis 2:22, "And the rib which the Lord God had taken from man made He a woman." One said that this "rib" was a face, the other that it was a tail. In support of the one who said it was a face, Psalm 139:5 says, "Behind and before have You formed me." The one who said it was a tail explained the words, "Behind and before have You formed me," as Rabbi Ammi said, that humankind was "behind," that is, later, in the work of creation, and "before" in punishment. The Gemara conceded that humankind was last in the work of creation, for God created humankind on the eve of the Sabbath. But if when saying that humankind was first for punishment, one means the punishment in connection with the serpent, Rabbi taught that, in conferring honor the Bible commences with the greatest, in cursing with the least important. Thus, in cursing, God began with the least, cursing first the serpent, then the people. The punishment of the Flood must therefore be meant, as Genesis 7:23 says, "And He blotted out every living substance which was upon the face of the ground, both man and cattle," starting with the people. In support of the one who said that Eve was created from a face, in Genesis 2:7, the word וַיִּיצֶר, wa-yitzer is written with two yuds. But the one who said Eve was created from a tail explained the word וַיִּיצֶר, wa-yitzer as Rabbi Simeon ben Pazzi said, "Woe is me because of my Creator (yotzri), woe is me because of my evil inclination (yitzri)!" In support of the one who said that Eve was created from a face, Genesis 5:2 says, "male and female God created them." But the one who said Eve was created from a tail explained the words, "male and female created He them," as Rabbi Abbahu explained when he contrasted the words, "male and female created He them," in Genesis 5:2 with the words, "in the image of God made God man," in Genesis 9:6. Rabbi Abbahu reconciled these statements by teaching that at first God intended to create two, but in the end created only one. In support of the one who said that Eve was created from a face, Genesis 2:22 says, "He closed up the place with flesh instead thereof." But the one who said Eve was created from a tail explained the words, "He closed up the place with flesh instead thereof," as Rabbi Jeremiah (or as some say Rav Zebid, or others say Rav Naḥman bar Isaac) said, that these words applied only to the place where God made the cut. In support of the one who said that Eve was created from a tail, Genesis 2:22 says, "God built." But the one who said that Eve was created from a face explained the words "God built" as explained by Rabbi Simeon ben Menasia, who interpreted the words, "and the Lord built the rib," to teach that God braided Eve's hair and brought her to Adam, for in the seacoast towns braiding (keli'ata) is called building (binyata). Alternatively, Rav Ḥisda said (or some say it was taught in a Baraita) that the words, "and the Lord built the rib," teach that God built Eve after the fashion of a storehouse, narrow at the top and broad at the bottom so as to hold the produce safely. So Rav Ḥisda taught that a woman is narrower above and broader below so as better to carry children.[150]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that if an orphan applied to the community for assistance to marry, the community must rent a house, supply a bed and necessary household furnishings, and put on the wedding, as Deuteronomy 15:8 says, "sufficient for his need, whatever is lacking for him." The Rabbis interpreted the words "sufficient for his need" to refer to the house, "whatever is lacking" to refer to a bed and a table, and "for him (לוֹ, lo)" to refer to a wife, as Genesis 2:18 uses the same term, "for him (לוֹ, lo)," to refer to Adam's wife, whom Genesis 2:18 calls "a helpmate for him."[151]

Rabbi Jeremiah ben Eleazar interpreted the words, "and God brought her to the man," in Genesis 2:22 to teach that God acted as best man to Adam, teaching that a man of eminence should not think it amiss to act as best man for a lesser man.[145]

Interpreting the words "And the man said: ‘This is now bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called Woman'" in Genesis 2:23, Rabbi Judah ben Rabbi taught that the first time God created a woman for Adam, he saw her full of discharge and blood. So God removed her from Adam and recreated her a second time.[152]

Rabbi José taught that Isaac observed three years of mourning for his mother Sarah. After three years he married Rebekah and forgot the mourning for his mother. Hence Rabbi José taught that until a man marries a wife, his love centers on his parents. When he marries a wife, he bestows his love upon his wife, as Genesis 2:24 says, "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and he shall cleave unto his wife."[153]

Genesis chapter 3

Hezekiah noted that in Genesis 3:3, Eve added to God's words by telling the serpent that she was not even permitted to touch the tree. Hezekiah deduced from this that one who adds to God's words in fact subtracts from them.[154]

A Midrash explained that because the serpent was the first to speak slander in Genesis 3:4–5, God punished the Israelites by means of serpents in Numbers 21:6 when they spoke slander. God cursed the serpent, but the Israelites did not learn a lesson from the serpent's fate, and nonetheless spoke slander. God therefore sent the serpent, who was the first to introduce slander, to punish those who spoke slander.[155]

Judah ben Padiah noted Adam's frailty, for he could not remain loyal even for a single hour to God's charge that he not eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, yet in accordance with Leviticus 19:23, Adam's descendants the Israelites waited three years for the fruits of a tree.[156]

Rabbi Samuel bar Naḥman said in Rabbi Jonathan's name that we can deduce from the story of the serpent in Genesis 3 that one should not plead on behalf of one who instigates idolatry. For Rabbi Simlai taught that the serpent had many pleas that it could have advanced, but it did not do so. And God did not plead on the serpent's behalf, because it offered no plea itself. The Gemara taught that the serpent could have argued that when the words of the teacher and the pupil are contradictory, one should surely obey the teacher's (and so Eve should have obeyed God's command).[157]

A Baraita reported that Rabbi taught that in conferring an honor, we start with the most important person, while in conferring a curse, we start with the least important. Leviticus 10:12 demonstrates that in conferring an honor, we start with the most important person, for when Moses instructed Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar that they should not conduct themselves as mourners, Moses spoke first to Aaron and only thereafter to Aaron's sons Eleazar and Ithamar. And Genesis 3:14–19 demonstrates that in conferring a curse, we start with the least important, for God cursed the serpent first, and only thereafter cursed Eve and then Adam.[158]

Rabbi Ammi taught that there is no death without sin, as Ezekiel 18:20 says, "The soul that sins ... shall die." The Gemara reported an objection based on the following Baraita: The ministering angels asked God why God imposed the death penalty on Adam (in Genesis 3). God answered that God gave Adam an easy command, and he violated it. The angels objected that Moses and Aaron fulfilled the whole Torah, but they died. God replied (in the words of Ecclesiastes 9:2), "There is one event [death] to the righteous and to the wicked; to the good and to the clean and to the unclean; ... as is the good, so is the sinner." The Gemara concluded that the Baraita refuted Rabbi Ammi, and there is indeed death without sin and suffering without iniquity.[159]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that when in Genesis 3:18, God told Adam, "Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to you," Adam began to cry and pleaded before God that he not be forced to eat out of the same trough with his donkey. But as soon as God told Adam in Genesis 3:19, "In the sweat of your brow shall you eat bread," Adam's mind was set at ease. Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish taught that humanity is fortunate that we did not remain subject to the first decree. Abaye (or others say Simeon ben Lakish) observed that we are still not altogether removed from the benefits of the first decree, as we eat herbs of the field (which come forth without effort).[160]

Rabbi Ḥama son of Rabbi Ḥanina taught that Genesis 3:21 demonstrates one of God's attributes that humans should emulate. Rabbi Ḥama asked what Deuteronomy 13:5 means in the text, "You shall walk after the Lord your God." How can a human being walk after God, when Deuteronomy 4:24 says, "[T]he Lord your God is a devouring fire"? Rabbi Ḥama explained that the command to walk after God means to walk after the attributes of God. As God clothes the naked—for Genesis 3:21 says, "And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife coats of skin, and clothed them"—so should we also clothe the naked. God visited the sick—for Genesis 18:1 says, "And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre" (after Abraham was circumcised in Genesis 17:26)—so should we also visit the sick. God comforted mourners—for Genesis 25:11 says, "And it came to pass after the death of Abraham, that God blessed Isaac his son"—so should we also comfort mourners. God buried the dead—for Deuteronomy 34:6 says, "And He buried him in the valley"—so should we also bury the dead.[161] Similarly, the Sifre on Deuteronomy 11:22 taught that to walk in God's ways means to be (in the words of Exodus 34:6) "merciful and gracious."[162]

Genesis chapter 4

It was taught in a Baraita that Issi ben Judah said that there are five verses in the Torah whose grammatical construction cannot be decided. (Each verse contains a phrase that a reader can link to the clause either before it or after it.) Among these five is the phrase "lifted up" (שְׂאֵת, seit) in Genesis 4:7. (One could read Genesis 4:7 to mean: If you do well, good! But you must bear the sin, if you do not do well. Or one could read Genesis 4:7 to mean, in the usual interpretation: If you do well, there will be forgiving, or "lifting up of face." And if you do not do well, sin couches at the door. In the first reading, the reader attaches the term "lifted up" to the following clause. In the second reading, the reader attaches the term "lifted up" to the preceding clause.)[163]

The Rabbis read God's admonition to Cain in Genesis 4:7 to describe the conflict that one has with one's Evil Inclination (yetzer hara). The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that Deuteronomy 11:18 says of the Torah, "So you fix (וְשַׂמְתֶּם, ve-samtem) these My words in your heart and in your soul." The Rabbis taught that one should read the word samtem rather as sam tam (meaning "a perfect remedy"). The Rabbis thus compared the Torah to a perfect remedy. The Rabbis compared this to a man who struck his son a strong blow, and then put a compress on the son's wound, telling his son that so long as the compress was on his wound, he could eat and drink at will, and bathe in hot or cold water, without fear. But if the son removed the compress, his skin would break out in sores. Even so, did God tell Israel that God created the Evil Inclination, but also created the Torah as its antidote. God told Israel that if they occupied themselves with the Torah, they would not be delivered into the hand of the Evil Inclination, as Genesis 4:7 says: "If you do well, shall you not be exalted?" But if Israel did not occupy themselves with the Torah, they would be delivered into the hand of the Evil Inclination, as Genesis 4:7 says: "sin couches at the door." Moreover, the Rabbis taught, the Evil Inclination is altogether preoccupied to make people sin, as Genesis 4:7 says: "and to you shall be his desire." Yet if one wishes, one can rule over the Evil Inclination, as Genesis 4:7 says: "and you shall rule over him." The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the Evil Inclination is hard to bear, since even God its Creator called it evil, as in Genesis 8:21, God says, "the desire of man's heart is evil from his youth." Rav Isaac taught that a person's Evil Inclination renews itself against that person daily, as Genesis 6:5 says, "Every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil every day." And Rabbi Simeon ben Levi (or others say Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish) taught that a person's Evil Inclination gathers strength against that person daily and seeks to slay that person, as Psalm 37:32 says, "The wicked watches the righteous, and seeks to slay him." And if God were not to help a person, one would not be able to prevail against one's Evil Inclination, for as Psalm 37:33 says, "The Lord will not leave him in his hand."[164]

Rav taught that the evil inclination resembles a fly, which dwells between the two entrances of the heart, as Ecclesiastes 10:1 says, "Dead flies make the ointment of the perfumers fetid and putrid." But Samuel said that the evil inclination is a like a kind of wheat (חִטָּה, chitah), as Genesis 4:7 says, "Sin (חַטָּאת, chatat) couches at the door."[165] (The Talmudic commentator Maharsha read Samuel's teaching to relate to the view that the forbidden fruit of which Adam ate was wheat.[166])