Architecture of Barcelona

This article contains translated text and the factual accuracy of the translation should be checked by someone fluent in Catalan and English. |

The architecture of Barcelona has undergone a parallel evolution alongside Catalan and Spanish architecture, reflecting the diverse trends found in the history of Western architecture. Throughout its historical development, Barcelona has been influenced by numerous cultures and civilizations, each contributing their artistic concepts and leaving a lasting legacy. The city's architectural heritage can be traced back to its earliest inhabitants, the Iberian settlers, followed by the Romans, Visigoths, and a brief Islamic period. In the Middle Ages, Catalan art, language, and culture flourished, with the Romanesque and Gothic periods particularly fostering artistic growth in the region.

History

During the Modern Age, when the Barcelona City was linked to the Hispanic Monarchy, the main styles were the Renaissance and the Baroque, developed from foreign styles coming from Italy and France. These styles were applied with various local variants, and although some authors claim that it was not a particularly splendid period, the quality of the works was in line with that of the state as a whole.[1]

The nineteenth century led to a certain economic and cultural revitalization, which reflected in one of the most fruitful periods in the city's architecture, Modernisme. Until the nineteenth century, Barcelona was corseted by its walls of medieval origin, being considered a military place, so its growth was limited. The situation changed with the demolition of the walls and the donation to the city of the Parc de la Ciutadella, which led to the expansion of the city along the adjoining plain, a fact that was reflected in the Eixample project designed by Ildefonso Cerdá. This was the largest territorial expansion of Barcelona. Another significant increase in the area of the city was the annexation of several bordering municipalities between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. All this meant the adaptation of the new urban spaces and an increase in municipal artistic commissions on public roads, which were also favored by various events held in the city such as the Universal Exhibition of 1888 and the International of 1929 or, more recently, for the Olympic Games of 1992 and the Universal Forum of the Cultures of 2004.

The twentieth century began with the updating of the various styles produced by Barcelonian architects, which connected with international currents. The architectural development in recent years and the commitment to design and innovation, as well as the link between urban planning, ecological values, and sustainability, have turned Barcelona into one of the most cutting-edge European cities in the architectural field, which has been recognized with numerous awards and distinctions such as the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1999 and the prize of the Venice Biennale in 2002.[2]

The architectural heritage of the city enjoys a special protection in virtue of the Law 9/1993 of the Catalan Cultural Heritage, that guarantees the protection, conservation, research and diffusion of the cultural heritage, with several degrees of coverage: level To (Cultural Good of National Interest), level B (Cultural Good of Local Interest), level C (Good of Interest Urbanístic) and level D (Good of Documentary Interest).[3]

Antiquity

Prehistory

There is scarce vestiges of prehistoric period to the city. If well it is ascertained the human presence in the paleolithic, the first rests regarding the architecture proceed of the neolíthic, period in which the human being went back sedentary and happened of a subsistència based in the hunting and the recol·lecció to an agrarian economy and farmer. These first vestiges proceed of finals of the neolític (3500 - 1800 BC), and manifest mainly for the practices funeràries with sepulcres of pit, that were used to be of quite a lot depth and revestides of slabs. An exponent thereof is the grave discovered the 1917 to the spilling southwest of the hill of Monterols, between the streets of Muntaner and Copèrnic; of imprecise dating, has 60 cm of high and 80 of wide, and was formed by slabs flat of irregular shape. Regarding habitacles, of this period only has found a bottom of cabin in what is the current station of Saint Andreu Comtal.[4]

Of the Bronze Age (1800–800 BC) there is equally few rests regarding the plan of Barcelona. The main proceed of a jaciment discovered the 1990 to the street of Saint Pau, where have found rests of fireplaces and sepultures of inhumació individual. Also they are surely of this period the rests found the 1931 to Can Casanoves, behind the Hospital of Saint Pau, where have found rests of walls of stone and the bottoms of three circular cabins of some 180 cm of diameter. They exist for other band witnesses written of two megalithic monuments, situated in Montjuïc and Field of the Harp, of those that nevertheless has not remained any rastre material. Finally, of the calcolític final there are some scarce rests of the called «culture of the fields of urns», found to the farm of Can Don Joan, to Horta, and to the south slope-oriental of the mountain of Montjuïc, between the paths of the Ancient Mill and the Source of the Mamella.

Iberian period

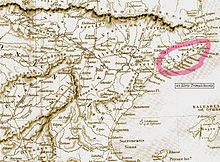

In the 6th century BC and the 1st century BC the plan of Barcelona was occupied by the Laietani, an Iberian people that occupied the current comarques of the Barcelonès, the Vallès, the Maresme and the Bass Llobregat. The Iberian architecture based in murs of tapial, with a system adovellat, with false arches and turns realised by approach of spun. Cities used to be located in acropolis, with towers and solid walls for the defence, within which the houses were located, of an irregular distribution, generally with a rectangular plan.[5]

In Barcelona there are hardly any Iberian architectural remains; the main vestiges of this culture were found in the hills of La Rovira, Peira and Putget, as well as in Santa Cruz de Olorde in Tibidabo, but they have not allowed establishing special characteristics with regard to funeral homes or sepulchres. The main remains come from Rovira, where in 1931 vestiges of an Iberian settlement were found that were destroyed when anti-aircraft batteries were installed during the Spanish Civil War. Apparently, it had a wall with two accesses, while located outside the walls there was a set of silos with 44 deposits carved into the rock.[6]

The main Iberian settlement in the area was in Montjuïc, possibly the 'Barkeno', although the urbanization of the mountain in recent years and its intensive use as a stone quarry throughout the history of the city has caused the loss of most remains. In 1928, nine large capacity silos were discovered in the Magòria area, which would probably be part of an agricultural surplus warehouse. On the other hand, in 1984 remains of a settlement were found on the southwest slope of the mountain, on a plot of about 2 or 3 hectares.

Roman period

In the third century BC C. the Romans arrived in the Iberian peninsula and began a colonization process that culminated in the incorporation of all Hispania into the Roman Empire. In the 1st century BC Barcino (Roman Barcelona) was founded, a small walled town that took the urban form of castrum and later oppidum. The Romans were great experts in civil architecture and engineering and provided roads, bridges, aqueducts and cities with a rational layout and basic services such as sewers.

The Barcino quarter was walled, with a perimeter of 1.5 km, which protected an area of 10.4 hectares. The first city wall, of simple factory, began to be built in the 1st century BC. It had few towers, only at the angles and at the gates of the walled perimeter. However, the first incursions of francs and Alamani from the 250s raised the need to reinforce the walls, which were extended in the fourth century. The new wall was built on the bases of the first, and was formed by a double wall of 2.4 metres, with space in half filled with stone and mortar. The wall consisted of 74 towers about 18 meters high, mostly rectangular.[7]

-

Remains of the Roman aqueduct, 1st century.

-

The remaining columns of the Temple of Augustus.

-

Roman tombs in the Plaça de la Vila de Madrid.

-

Remains of the roman wall in Plaça dels Traginers.

-

Remains of the roman wall in Carrer de la Tapineria.

-

Roman ruins in the Museum of the History of Barcelona.

-

Remains of a roman column in the Museum of the History of Barcelona.

See also

- Parks and gardens of Barcelona

- Street furniture in Barcelona

- The Cerdá Plan

- Urban planning of Barcelona

Notes

References

- DDAA. Art de Catalunya 3: Urbanisme, arquitectura civil i industrial. Barcelona: Edicions L'isard, 1998.

- DDAA. Arte contemporáneo. Barcelona: Folio, 2006. ISBN 84-413-2179-5

- DDAA. Barcelona. Guia de la ciutat. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2002. ISBN 84-7609-702-6

- DDAA. El llibre d'or de l'art català. Barcelona: Edicions Primera Plana, 1997.

- DDAA. Els Barris de Barcelona I. Ciutat Vella, L'Eixample. Barcelona: Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana, 1999. ISBN 84-412-2768-3

- DDAA. Enciclopèdia Catalana Bàsica. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana, 1996.

- DDAA. Gaudí. Hàbitat, natura i cosmos. Barcelona: Lunwerg, 2001. ISBN 84-7782-799-0

- DDAA. Història de Barcelona 1. La ciutat antiga. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia catalana, 1991. ISBN 84-7739-179-3

- DDAA. Història de Barcelona 2. La formació de la Barcelona medieval. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia catalana, 1992. |ISBN 84-7739-398-2

- DDAA. Història de Barcelona 6. La ciutat industrial (1833-1897). Barcelona: Enciclopèdia catalana, 1995. ISBN 84-7739-809-7

- DDAA. Història de l'art català. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2005. ISBN 84-297-1997-0

- DDAA. Sagnier. Arquitecte, Barcelona 1858-1931. Barcelona: Antonio Sagnier Bassas, 2007. ISBN 978-84-612-0215-7

- Albert de Paco, José María. El arte de reconocer los estilos arquitectónicos. Barcelona: Optima, 2007. ISBN 978-84-96250-72-7

- Añón Feliú, Carmen; Luengo, Mónica. Jardines de España. Madrid: Lunwerg, 2003. ISBN 84-9785-006-8

- Azcárate Ristori, José María de; Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso Emilio; Ramírez Domínguez, Juan Antonio. Historia del Arte. Madrid: Anaya, 1983. ISBN 84-207-1408-9

- Bahamón, Alejandro; Losantos, Àgata. Barcelona. Atlas histórico de arquitectura. Barcelona: Parramón, 2007.

- Baldellou, Miguel Ángel; Capitel, Antón. Summa Artis XL: Arquitectura española del siglo XX. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 2001. ISBN 84-239-5482-X

- Barjau, Santi. Enric Sagnier. Barcelona: Labor, 1992. ISBN 84-335-4802-6

- Barral i Altet, Xavier; Beseran, Pere; Canalda, Sílvia; Guardià, Marta; Jornet, Núria. Guia del Patrimoni Monumental i Artístic de Catalunya, vol. 1. Barcelona: Pòrtic, 2000. ISBN 84-7306-947-1

- Bassegoda i Nonell, Joan. Gaudí o espacio, luz y equilibrio. Madrid: Criterio, 2002. ISBN 84-95437-10-4

- Bergós i Massó, Joan. Gaudí, l'home i l'obra. Barcelona: Lunwerg, 1999. ISBN 84-7782-617-X

- Chilvers, Ian. Diccionario de arte. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2007. ISBN 978-84-206-6170-4

- Corredor-Matheos, Josep. Història de l'art català vol. IX. La segona meitat del segle XX. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2001. ISBN 84-297-4120-8

- Crippa, Maria Antonietta. Gaudí. Köln: Taschen, 2007. ISBN 978-3-8228-2519-8

- Dalmases, Núria de; José i Pitarch, Antoni. Història de l'art català III. L'art gòtic, s. XIV-XV. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1998. ISBN 84-297-2104-5

- Fernández Polanco, Aurora. Fin de siglo: Simbolismo y Art Nouveau. Madrid: Historia 16, 1989. DL M. 32415-1989.

- Flores, Carlos. Les lliçons de Gaudí. Barcelona: Ed. Empúries, 2002. ISBN 84-7596-949-6

- Fontbona, Francesc. Història de l'art català VI. Del neoclassicisme a la Restauració 1808-1888. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1997. ISBN 84-297-2064-2

- Fontbona, Francesc; Miralles, Francesc. Història de l'art català VII. Del modernisme al noucentisme 1888-1917. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2001. ISBN 84-297-2282-3

- Gabancho, Patrícia. Guía. Parques y jardines de Barcelona. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, Imatge i Producció Editorial, 2000. ISBN 84-7609-935-5

- Galofré, Jordi. Historia de Catalunya. Barcelona: Primera Plana, 1992.

- Garriga, Joaquim. Història de l'art català IV. L'època del Renaixement, s. XVI. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1986. ISBN 84-297-2437-0

- Garrut, Josep Maria. L'Exposició Universal de Barcelona de 1888. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, Delegació de Cultura, 1976. ISBN 84-500-1498-0

- Gausa, Manuel; Cervelló, Marta; Pla, Maurici. Barcelona: guía de arquitectura moderna 1860-2002. Barcelona: ACTAR, 2002. ISBN 84-89698-47-3

- Giorgi, Rosa. El siglo XVII. Barcelona: Electa, 2007. ISBN 978-84-8156-420-4

- González, Antonio Manuel. Las claves del arte. Últimas tendencias. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991. ISBN 84-320-9702-0

- Grandas, M. Carmen. L'Exposició Internacional de Barcelona de 1929. Sant Cugat del Vallès: Els llibres de la frontera, 1988. ISBN 84-85709-68-3

- Hernàndez i Cardona, Francesc Xavier. Barcelona, Història d'una ciutat. Barcelona: Llibres de l'Índex, 2001. ISBN 84-95317-22-2

- Huertas, Josep Maria; Capilla, Antoni; Maspoch, Mònica. Ruta del Modernismo. Barcelona: Institut Municipal del Paisatge Urbà i la Qualitat de Vida, Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2005. ISBN 84-934169-3-2

- Lacuesta, Raquel; González, Antoni. Barcelona, guía de arquitectura 1929-2000. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1999. ISBN 84-252-1801-2

- Lacuesta, Raquel; González, Antoni. Guía de arquitectura modernista en Cataluña. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1997. ISBN 84-252-1430-0

- Lecea, Ignasi de; Fabre, Jaume; Grandas, Carme; Huertas, Josep M.; Remesar, Antoni Art públic de Barcelona. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona i Àmbit Serveis Editorials, 2009. ISBN 978-84-96645-08-0

- Maspoch, Mònica. Galeria d'autors. Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona. Barcelona: Institut Municipal del Paisatge Urbà i la Qualitat de Vida, Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2008. ISBN 978-84-96696-02-0

- Midant, Jean-Paul. Diccionario Akal de la Arquitectura del siglo XX. Madrid: Akal, 2004. ISBN 84-460-1747-4

- Miralles, Francesc. Història de l'art català VIII. L'època de les avantguardes 1917-1970. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2001. ISBN 84-297-1998-9

- Miralles, Roger. Barcelona, arquitectura modernista y noucentista 1888-1929. Barcelona: Polígrafa, 2008. ISBN 978-84-343-1178-7

- Miralles, Roger; Sierra, Pau. Barcelona, arquitectura contemporánea 1979-2012. Barcelona: Polígrafa, 2012. ISBN 978-84-343-1307-1

- Montaner, Josep Maria. Arquitectura contemporània a Catalunya. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2005. ISBN 84-297-5669-8

- Navascués Palacio, Pedro. Summa Artis XXXV-II. Arquitectura española (1808-1914). Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 2000. ISBN 84-239-5477-3

- Páez de la Cadena, Francisco. Historia de los estilos en jardinería. Madrid: Istmo, 1998. ISBN 84-7090-127-3

- Permanyer, Lluís. Biografia del Passeig de Gràcia. Barcelona: La Campana, 1994. ISBN 84-86491-91-6.

- Pla, Maurici. Catalunya. Guia d'arquitectura moderna 1880-2007. Sant Lluís (Menorca): Triangle, 2007. ISBN 978-84-8478-007-6

- Roig, Josep L. Historia de Barcelona. Barcelona: Primera Plana S.A., 1995. ISBN 84-8130-039-X

- Rubio, Albert. Barcelona, arquitectura antigua (siglos I-XIX). Barcelona: Polígrafa, 2009. ISBN 978-84-343-1212-8

- Sánchez Vidiella, Àlex. Atlas de arquitectura del paisaje. Barcelona: Loft, 2008. ISBN 978-84-92463-27-5

- Soler, Narcís; Guitart i Duran, Josep; Barral i Altet, Xavier; Bracons Clapés, Josep. Art de Catalunya 4: Arquitectura religiosa antiga i medieval. Barcelona: Edicions L'isard, 1999. ISBN 84-89931-13-5

- Triadó, Joan Ramon; Barral i Altet, Xavier. Art de Catalunya 5: Arquitectura religiosa moderna i contemporània. Barcelona: Edicions L'isard, 1999. ISBN 84-89931-14-3

- Triadó, Joan Ramon. Història de l'art català V. L'època del Barroc, s. XVII-XVIII. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1984. ISBN 84-297-2204-1

- Viladevall-Palaus, Ignasi. «Cincuenta parques, más dos». Cuadernos Cívicos La Vanguardia. La Vanguardia Ediciones [Barcelona], 3, 2004.

- Villoro, Joan; Riudor, Lluís. Guia dels espais verds de Barcelona. Aproximació històrica. Barcelona: La Gaia Ciència, 1984. ISBN 84-7080-207-0